1.5: Polar Coordinates

- Page ID

- 6470

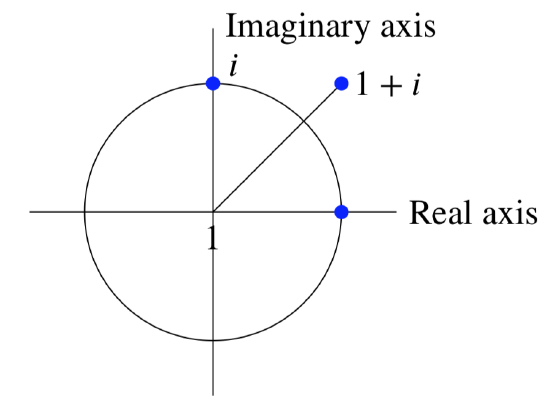

In the figures above we have marked the length \(r\) and polar angle \(\theta\) of the vector from the origin to the point \(z = x + iy\). These are the same polar coordinates you saw previously. There are a number of synonyms for both \(r\) and \(\theta\)

\(r =|z|\) = magnitude = length = norm = absolute value = modulus

\(\theta = \text{arg} (z)\) = argument of \(z\) = polar angle of \(z\)

You should be able to visualize polar coordinates by thinking about the distance \(r\) from the origin and the angle \(\theta\) with the \(x\)-axis.

Let's make a table of \(z\), \(r\) and \(\theta\) for some complex numbers. Notice that \(\theta\) is not uniquely defined since we can always add a multiple of \(2\pi\) to \(\theta\) and still be at the same point in the plane.

\(\begin{array} {ccll} {z = a + bi} & {r} & {\theta} & { } \\ {1} & {1} & {0, 2\pi , 4\pi , ...} & {\text{Argument = 0, means}\, z \,\text{is along the } x\text{-axis}} \\ {i} & {1} & {\pi /2, \pi /2 + 2\pi ...} & {\text{Argument = } \pi /2, \text{ means}\, z \,\text{is along the } y\text{-axis}} \\ {1 + i} & {\sqrt{2}} & {\pi /4 , \pi /4 + 2\pi ...} & {\text{Argument = } \pi /4, \text{ means}\, z \,\text{is along the ray at } 45^{\circ} \text{to the } x\text{-axis}} \end{array}\)

When we want to be clear which value of \(\theta\) is meant, we will specify a branch of arg. For example, \(0 \le \theta < 2\pi\) or \(-\pi < \theta \le \pi\). This will be discussed in much more detail in the coming weeks. Keeping careful track of the branches of arg will turn out to be one of the key requirements of complex analysis.