10.2: Application - Long-Term Promissory Notes

- Page ID

- 22125

How do all of those "don't pay until . . ." plans work? The retail industry overflows with financing plans specifically designed to attract customers to purchase merchandise on credit. Most of these offers include terms such as "no money down" and "no payments for x months." You can find these plans at most furniture retailers such as The Brick and Leon's, electronic retailers such as Best Buy, along with many other establishments including jewelry stores and sleep centers.

But have you ever considered how this works on the business side? If every customer purchased merchandise under these no-money-required plans, how would the retailer stay in business? For example, perhaps The Brick’s customers purchase furniture in January 2014 that they do not have to pay for until January 2016. During these two years, The Brick does not get paid for the products sold; however, it has paid its suppliers for the merchandise. How can a retailer stay in business while it waits for all those postponed payments?

Consumers generally do not read the fine print on their contracts with these retailers. Few consumers realize that the retailers often sell these contracts (sometimes immediately) to finance companies they have partnered with. While the consumer sees no noticeable difference, behind the scenes the retailer receives cash today in exchange for the right to collect payment in the future when the contract becomes due. That way the finance company becomes responsible for collecting on the loan to the consumer.

This section introduces the mathematics behind the sale of promissory notes between companies. Recall from Section 8.4 that a promissory note, more commonly called a note, is a written debt instrument that details a promise made by a buyer to pay a specified amount to a seller at a predetermined and specified time. If the debt allows for interest to accumulate, then it is called an interest-bearing promissory note. If there is no allowance for interest, then it is called a non-interest-bearing promissory note. Interest-bearing notes are covered in this section and non-interest notes are discussed in the next section. When promissory notes extend more than one year, they involve compound interest instead of simple interest.

Interest-Bearing Promissory Notes

When you participate in "don't pay until . . ." promotions, you create a promissory note in which you promise to pay for your goods within the time interval stated. These promotions commonly carry 0% interest if paid before the stated deadline, so the notes are non-interest-bearing promissory notes. However, failure to pay the note before the deadline transforms the note into an interest-bearing note for which interest is retroactive to the date of sale, usually at a very high rate of interest such as 21%.

The mathematics of interest-bearing promissory notes deal primarily with the sale of long-term promissory notes between organizations. When the note is sold, the company buying it (usually a finance company) purchases the maturity value of the note and not the principal of the note. To the finance company, the transaction is an investment from which it intends to earn a profit through the difference between maturity value and purchase price. Thus, the finance company discounts the maturity value of the note using a discount rate that permits it to invest a smaller sum of money today to receive a larger sum of money in the future. The company selling the note is willing to take the smaller sum of money to cash in its accounts receivables and eliminate the risk of default on the debt.

How It Works

Recall that in simple interest the sale of short-term promissory notes involved three steps. You use the same three step sequence for long-term compound interest promissory notes. On long-term promissory notes, a three-day grace period is not required, so the due date of the note is the same as the legal due date of the note.

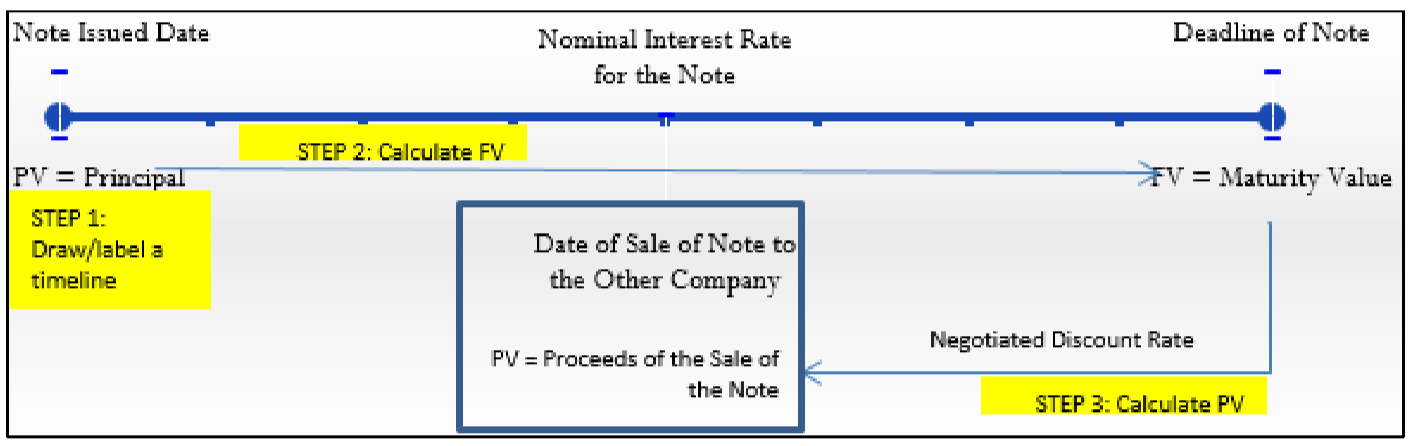

Step 1: Draw a timeline, similar to the one on the next page, detailing the original promissory note and the sale of the note.

Step 2: Take the initial principal on the date of issue and determine the note's future value at the stated deadline using the stated rate of interest attached to the note. As most long-term promissory notes have a fixed rate of interest, this involves a future value calculation using Formula 9.3.

- Calculate the periodic interest rate using Formula 9.1, \(i=\dfrac{1 Y}{C Y}\).

- Calculate the number of compounding periods between the issue date and due date using Formula 9.2, \(N = CY × \text {Years}\).

- Solve for the future value using Formula 9.3, \(FV=PV\left(1+i\right)^N\).

Step 3: Using the date of sale, discount the maturity value of the note using a new negotiated discount rate of interest to determine the proceeds of the sale. Most commonly the negotiated discount rate is a fixed rate and involves a present value calculation using Formula 9.3.

- Calculate the new periodic interest rate using Formula 9.1, \(i=\dfrac{1 Y}{C Y}\).

- Calculate the number of compounding periods between the date of sale of the note and the due date using Formula 9.2, \(N = CY × \text {Years}\). Remember to use the \(CY\) for the discount rate, not the \(CY\) for the original interest rate.

- Solve for the present value using Formula 9.3, \(FV=PV\left(1+i\right)^N\), rearranging for \(PV\).

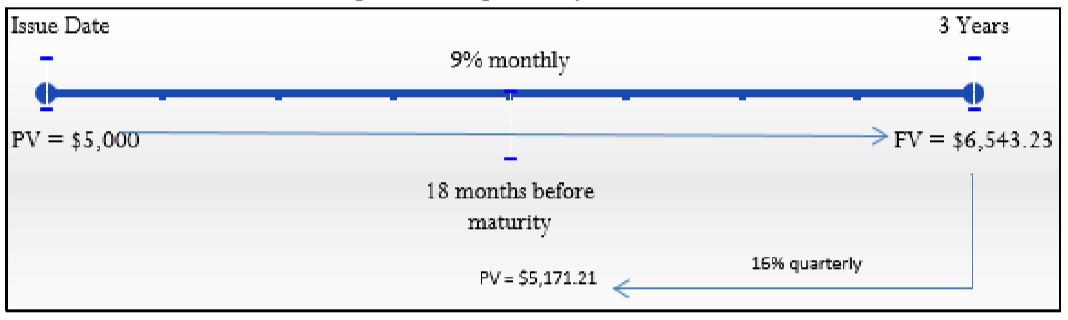

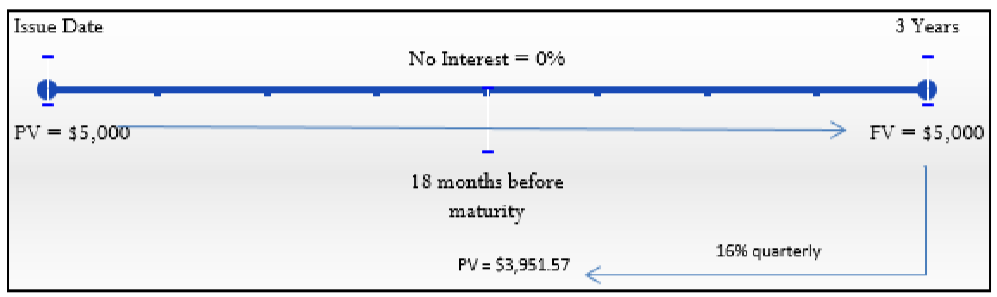

Assume that a three-year $5,000 promissory note with 9% compounded monthly interest is sold to a finance company 18 months before the due date at a discount rate of 16% compounded quarterly.

Step 1: The timeline to the right illustrates the situation.

Step 2a: The periodic interest rate on the note is \(i\) = 9%/12 = 0.75%.

Step 2b: The term is three years with monthly compounding, resulting in \(N\) = 12 × 3 = 36.

Step 2c: The maturity value of the note is \(FV\) = $5,000(1 + 0.0075)36 = $6,543.23.

Step 3a: Now sell the note. The periodic discount rate is \(i\) = 16%/4 = 4%.

Step 3b: The time before the due date is 1½ years at quarterly compounding. The number of compounding periods is N = 4 × 1½ = 6.

Step 3c: The proceeds of the sale of the note is \(\$6,543.23 = PV(1 + 0.04)^6\), where PV= $5,171.21. The finance company purchases the note (invests in the note) for $5,171.21. Eighteen months later, when the note is paid, it receives $6,543.23.

Important Notes

The assumption behind the three-step procedure for selling a long-term promissory note is that the process starts with the issuance of the note and ends with the proceeds of the sale. However, mathematically you may deal with any part of the transaction as an unknown. For example, perhaps the details of the original note are known, the finance company's offer on the date of sale is known, but the quarterly discounted rate used by the finance company needs to be calculated.

The best strategy in any of these scenarios is always to execute step 1 and create a timeline. Identify the known variables to visualize the process, then recognize any variable(s) remaining unknown. Keeping in mind how the selling of a promissory note works, you can adapt the three-step promissory note procedure using any of the techniques discussed in Chapter 9. Some examples of these adaptations include the following:

- The discounted rate is unknown. Execute steps 1 and 2 normally. In step 3, solve for i (then \(IY\)) instead of \(PV\).

- The original principal of the note is unknown. Execute step 1 normally. Work with step 3, but solve for \(FV\) instead of \(PV\). Then work with step 2 and solve for \(PV\) instead of \(FV\).

- The length of time by which the date of sale precedes the maturity date is unknown. Execute steps 1 and 2 normally. In step 3, solve for \(N\) instead of \(PV\). As you can see, the three steps always stay intact. However, you may need to reverse steps 2 and 3 or calculate a different unknown variable.

Things To Watch Out For

In working with compound interest long-term promissory notes, the most common mistakes relate to the maturity value and the two interest rates.

- Maturity Value. Remember that the company purchasing the note is purchasing the maturity value of the note, not its principal on the issue date. Any promissory note situation always involves the maturity value of the promissory note on its due date.

- Two Interest Rates. The sale involves two interest rates: an interest rate tied to the note itself and an interest rate (the discount rate) used by the purchasing company to acquire the note. Do not confuse these two rates.

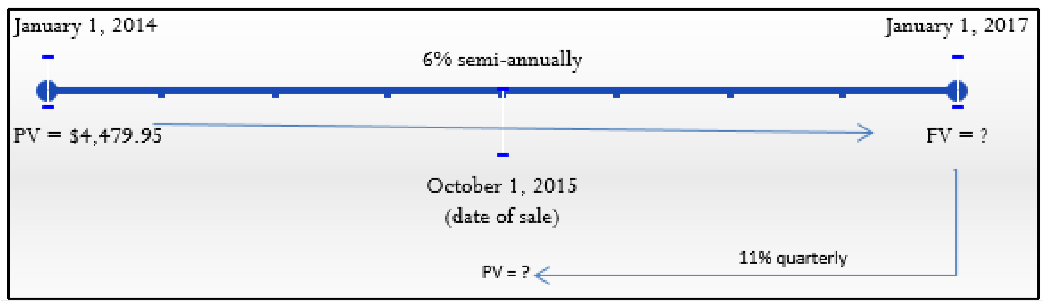

Jake's Fine Jewelers sold a diamond engagement ring to a customer for $4,479.95 and established a promissory note under one of its promotions on January 1, 2014. The note requires 6% compounded semi-annually interest and is due on January 1, 2017. On October 1, 2015, Jake's Fine Jewellers needed the money and sold the note to a finance company at a discount rate of 11% compounded quarterly. What are the proceeds of the sale?

Solution

Find the proceeds of the sale for Jake's Fine Jewellers on October 1, 2013. This is the present value of the note (\(PV\)) based on the maturity value and the discount rate.

What You Already Know

Step 1:

The issue date, maturity date, principal, interest rate on the note, date of sale, and the discount rate are known, as illustrated in the timeline.

How You Will Get There

Step 2a:

Working with the promissory note itself, calculate the periodic interest rate by applying Formula 9.1.

Step 2b:

Calculate the number of compound periods using Formula 9.2.

Step 2c:

Calculate the maturity value of the note using Formula 9.3.

Step 3a:

Working with the sale of the note, calculate the discount periodic interest rate by applying Formula 9.1.

Step 3b:

Calculate the number of compound periods elapsing between the sale and maturity. Use Formula 9.2.

Perform

Step 2a:

\[IY=6 \%, CY=2, i=6 \% / 2=3 \% \nonumber \]

Step 2b:

Years = January 1, 2017 − January 1, 2014 = 3 Years, \(N\) = 2 × 3 = 6

Step 2c:

\[\begin{aligned} PV&=\$ 4,479.95\\ FV&=\$ 4,479.95(1+0.03)^{6}=\$ 5,349.29 \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Step 3a:

\[IY=11 \%, CY=4, i=11 \% / 4=2.75 \% \nonumber \]

Step 3b:

Years = January 1, 2017 − October 1, 2015 = 1¼ Years, \(N\) = 4 × 1¼ = 5

Step 3c:

\[\begin{aligned} \$ 5,349.29 &=PV(1+0.0275)^{5} \\ PV &=\dfrac{\$ 5,349.29}{1.0275^{5}}\\ &=\$ 4,670.75 \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Calculator Instructions

| Part | N | I/Y | PV | PMT | FV | P/Y | C/Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maturity | 6 | 6 | -4479.95 | 0 | Answer: 5,349.294586 | 2 | 2 |

| Sale | 5 | 11 | Answer: -4,670.753954 | \(\surd\) | 5349.29 | 4 | 4 |

Jake's fine Jewelers made the sale for $4,479.95 on January 1, 2014. On October 1, 2015, it receives $4,670.75 in proceeds of the sale to the finance company. The finance company holds the note until maturity and receives $5,349.29 from the customer.

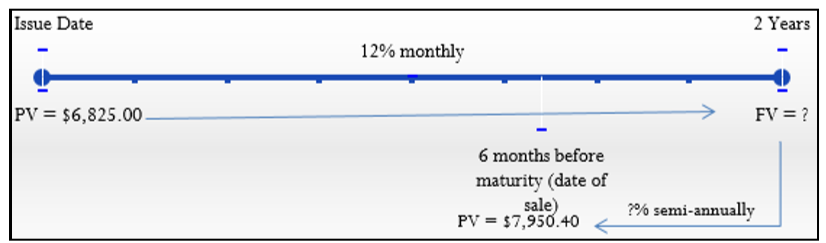

A $6,825 two-year promissory note bearing interest of 12% compounded monthly is sold six months before maturity to a finance company for proceeds of $7,950.40. What semi-annually compounded discount rate was used by the finance company?

Solution

Calculate the semi-annually compounded negotiated discount rate (\(IY\)) used by the finance company when it purchased the note.

What You Already Know

Step 1:

The term, principal, promissory note interest rate, date of sale, and proceeds amount are known, as shown in the timeline.

How You Will Get There

Step 2a:

Working with the promissory note itself, calculate the periodic interest rate by applying Formula 9.1.

Step 2b:

Calculate the number of compound periods using Formula 9.2.

Step 2c:

Calculate the maturity value of the note using Formula 9.3.

Step 3a:

Note the \(CY\) on the discount rate.

Step 3b:

Calculate the number of compound periods elapsing between the sale and before maturity. Use Formula 9.2.

Step 3c:

Calculate the periodic discount rate used by the finance company by applying Formula 9.3 and rearranging for \(i\). Then substitute into Formula 9.1 and rearrange for \(IY\).

Perform

Step 2a:

\[IY=12 \%, CY=12, i=12 \% / 12=1 \% \nonumber \]

Step 2b:

Years = 2, \(N\) = 12 × 2 = 24

Step 2c:

\[PV=\$ 6,825.00, FV=\$ 6,825.00(1+0.01)^{24}=\$ 8,665.94 \nonumber \]

Step 3a:

\(CY\) = 2

Step 3b:

Years = 6 months = ½ Year, \(N\) = 2 × ½ = 1

Step 3c:

Solve for \(i\):

\[\begin{aligned} \$ 8,665.94&=\$ 7,950.40(1+i)^1 \\ 1.090000&=1+i \\ i&=0.090000 \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Solve for \(IY: 0.090000 = IY \div 2\)

\(IY\) = 0.180001 or 18.0001% compounded semi-annually (most likely 18%; the difference is due to a rounding error)

Calculator Instructions

| Part | N | I/Y | PV | PMT | FV | P/Y | C/Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maturity | 24 | 12 | -6825 | 0 | Answer: 8,665.938976 | 12 | 12 |

| Discount Rate | 1 | Answer: 18.0001 | -7950.40 | \(\surd\) | 8665.94 | 2 | 2 |

The sale of the promissory note is based on a maturity value of $8,665.94. The finance company used a discount rate of 18% compounded semi-annually to arrive at proceeds of $7,950.40.

Non-interest-Bearing Promissory Notes

A non-interest-bearing promissory note involves either truly having 0% interest or else already including a flat fee or rate within the note’s face value. Therefore, the principal amount and maturity amount of the promissory note are the same.

How It Works

A non-interest-bearing note simplifies the calculations involved with promissory notes. Instead of performing a future value calculation on the principal in step 2, your new step 2 involves equating the present value and maturity value to the same amount (\(PV = FV\)). You then proceed with step 3.

Assume a three-year $5,000 non-interest-bearing promissory note is sold to a finance company 18 months before the due date at a discount rate of 16% compounded quarterly.

Step 1: The timeline is illustrated here.

Step 2: The maturity value of the note three years from now is the same as the principal, or \(FV\) = $5,000.

Step 3a: Now sell the note. The periodic discount rate is \(i\) = 16%/4 = 4%.

Step 3b: The time before the due date is 1½ years at quarterly compounding. The number of compounding periods is \(N\) = 4 × 1½ = 6.

Step 3c: The proceeds of the sale of the note is \(\$5,000 = PV(1 + 0.04)^6\), or PV = $3,951.57. The finance company purchases the note (invests in the note) for $3,951.57. Eighteen months later, when the note is paid, it receives $5,000.

If a non-interest-bearing note is sold to another company at a discount rate, are the proceeds of the sale more than, equal to, or less than the note?

- Answer

-

Less than the note. The maturity value is discounted to the date of sale.

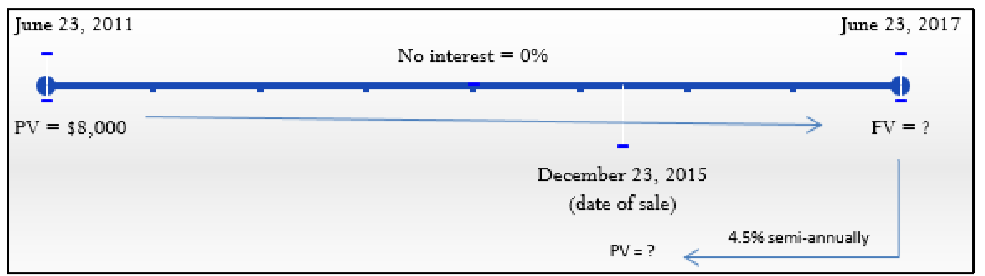

A five-year, noninterest-bearing promissory note for $8,000 was issued on June 23, 2011. The plan is to sell the note at a discounted rate of 4.5% compounded semi-annually on December 23, 2015. Calculate the expected proceeds on the note.

Solution

What You Already Know

Step 1:

The principal, non-interest on the note, issue date, due date, discount rate, and date of sale are known, as illustrated in the timeline.

How You Will Get There

Step 2:

Equate the \(FV\) of the note with the principal of the note.

Step 3a:

Working with the sale of the note, calculate the discount periodic interest rate by applying Formula 9.1.

Step 3b:

Calculate the number of compound periods elapsing between the sale and maturity. Use Formula 9.2.

Step 3c:

Calculate the proceeds of the sale by using Formula 9.3, rearranging for \(PV\).

Perform

Step 2:

\(FV = PV\) = $8,000

Step 3a:

\[IY=4.5 \%, CY=2, i=4.5 \% / 2=2.25 \% \nonumber \]

Step 3b:

Years = June 23, 2017 − December 23, 2015 = 1½ Years, \(N\) = 2 × 1½ = 3

Step 3c:

\[\begin{aligned} \$ 8,000 &=PV(1+0.0225)^{3} \\ PV &=\dfrac{\$ 8,000}{1.0225^{3}}\\ &=\$ 7,483.42 \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Calculator Instructions

| N | I/Y | PV | PMT | FV | P/Y | C/Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 4.5 | Answer: -7,483.418564 | 0 | 8000 | 2 | 2 |

The expected proceeds are $7,483.42 on December 23, 2015, with a maturity value of $8,000.00 on June 23, 2017.