3.1: The Euclidean Algorithm

- Page ID

- 60308

Lemma 3.1

In the division algorithm of Definition2.4, we have \(\gcd(r_{1},r_{2}) = \gcd(r_{2}, r_{3})\).

- Proof

-

On the one hand, we have \(r_{1} = r_{2}q_{2}+r_{3}\), and so any common divisor of \(r_{2}\) and \(r_{3}\) must also be a divisor of \(r_{1}\) (and of \(r_{2}\)). Vice versa, since \(r_{1}-r_{2}q_{2} = r_{3}\), we have that any common divisor of \(r_{1}\) and \(r_{2}\) must also be a divisor of \(r_{3}\) (and of \(r_{2}\)).

Thus by calculating \(r_{3}\), the residue of \(r_{1}\) modulo \(r_{2}\), we have simplified the computation of \(\gcd (r_{1}, r_{2})\). This is because \(r_{3}\) is strictly smaller (in absolute value) than both \(r_{1}\) and \(r_{2}\). In turn, the computation of \(\gcd (r_{2}, r_{3})\) can be simplified similarly, and so the process can be repeated. Since the \(r_{i}\) form a monotone decreasing sequence in \(\mathbb{N}\), this process must end when \(r_{n}+1 = 0\) after a finite number of steps. We then have \(gcd(r_{1},r_{2}) = gcd(r_{n},0) = r_{n}\).

Corollary 3.2

Given \(r_{1} > r_{2} > 0\), apply the division algorithm until \(r_{n} > r_{n+1} = 0\). Then \(\gcd (r_{1}, r_{2}) = \gcd(r_{n}, 0) = r_{n}\). Since \(r_{i}\) is decreasing, the algorithm always ends.

Definition 3.3

The repeated application of the division algorithm to compute \(\gcd(r_{1}, r_{2})\) is called the Euclidean algorithm.

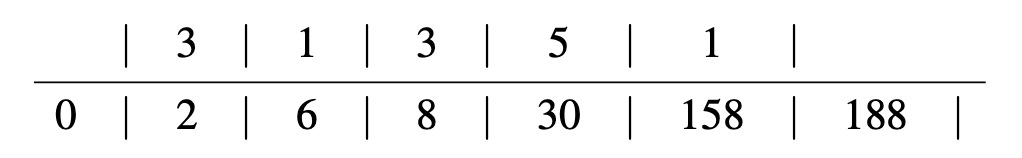

We now give a framework to reduce the messiness of these repeated computations. Suppose we want to compute \(\gcd(188, 158)\). We do the following computations:

\[188 = 158·1+30 \nonumber\]

\[158 = 30·5+8 \nonumber\]

\[30 = 8·3+6 \nonumber\]

\[8 = 6·1+2 \nonumber\]

\[6 = 2·3+0 \nonumber\]

We see that \(\gcd(188,158) = 2\). The numbers that multiply the \(r_{i}\) are the quotients of the division algorithm (see the proof of Lemma 2.3). If we call them \(q_{i-1}\), the computation looks as follows:

\[\begin{array} {c} {r_{1} = r_{2} q_{2}+r_{3}}\\ {r_{2} = r_{3} q_{3}+r_{4}}\\ {\vdots}\\ {r_{n-3} = r_{n-2} q_{n-2}+r_{n-3}}\\ {r_{n-2} = r_{n-1} q_{n-1}+r_{n-2}}\\ {r_{n-1} = r_{n} q_{n}+0} \end{array}\]

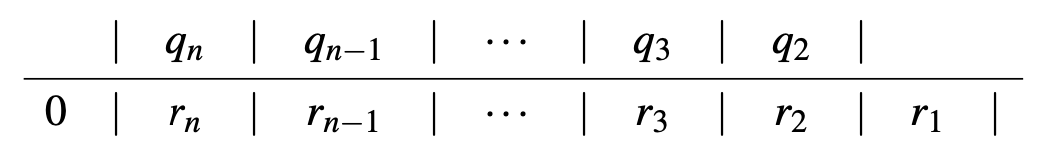

where we use the convention that \(r_{n+1} = 0\) while \(r_{n} \ne 0\). Observe that with that convention, (3.1) consists of \(n-1\) steps. A much more concise form (in part based on a suggestion of Katahdin [16]) to render this computation is as follows.

Thus, each step \(r_{i+1} |r_{i}|\) is similar to the usual long division, except that its quotient \(q_{i+1}\) is placed above \(r_{i+1}\) (and not above \(r_{i}\)), while its remainder \(r_{i+2}\) is placed all the way to the left of of \(r_{i+1}\). The example we worked out before now it looks like:

There is a beautiful visualization of this process outlined in exercise 3.4.