10.1: What is a Tree?

- Page ID

- 80540

Definition

What distinguishes trees from other types of graphs is the absence of certain paths called cycles. Recall that a path is a sequence of consecutive edges in a graph, and a circuit is a path that begins and ends at the same vertex.

Definition \(\PageIndex{1}\): Cycle

A cycle is a circuit whose edge list contains no duplicates. It is customary to use \(C_n\) to denote a cycle with \(n\) edges.

The simplest example of a cycle in an undirected graph is a pair of vertices with two edges connecting them. Since trees are cycle-free, we can rule out all multigraphs having at least one pair of vertices connected with two or more edges from consideration as trees.

Trees can either be undirected or directed graphs. We will concentrate on the undirected variety in this chapter.

Definition \(\PageIndex{2}\): Tree

An undirected graph is a tree if it is connected and contains no cycles or self-loops.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Some Trees and Non-Trees

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Some trees and some non-trees

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Some trees and some non-trees- Graphs i, ii and iii in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) are all trees, while graphs iv, v, and vi are not trees.

- A \(K_2\) is a tree. However, if \(n\geq 3\text{,}\) a \(K_n\) is not a tree.

- In a loose sense, a botanical tree is a mathematical tree. There are usually no cycles in the branch structure of a botanical tree.

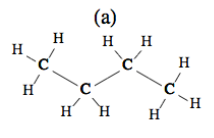

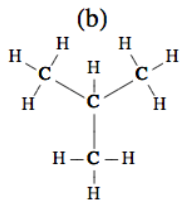

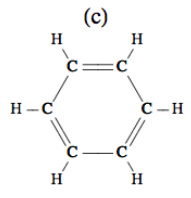

- The structures of some chemical compounds are modeled by a tree. For example, butane Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) consists of four carbon atoms and ten hydrogen atoms, where an edge between two atoms represents a bond between them. A bond is a force that keeps two atoms together. The same set of atoms can be linked together in a different tree structure to give us the compound isobutane Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). There are some compounds whose graphs are not trees. One example is benzene Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Butane

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Butane Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Isobutane

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Isobutane Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Benzene

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): BenzeneOne type of graph that is not a tree, but is closely related, is a forest.

Definition \(\PageIndex{3}\): Forest

A forest is an undirected graph whose components are all trees.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): A Forest

The top half of Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) can be viewed as a forest of three trees. Graph (vi) in this figure is also a forest.

Conditions for a graph to be a tree

We will now examine several conditions that are equivalent to the one that defines a tree. The following theorem will be used as a tool in proving that the conditions are equivalent.

Lemma \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Let \(G = (V, E)\) be an undirected graph with no self-loops, and let \(v_a, v_b\in V\text{.}\) If two different simple paths exist between \(v_a\) and \(v_b\text{,}\) then there exists a cycle in \(G\text{.}\)

- Proof

-

Let \(p_1= \left(e_1, e_2, \ldots , e_m \right)\) and \(p_2=\left(f_1,f_2,\ldots , f_n\right)\) be two different simple paths from \(v_a\) to \(v_b\text{.}\) The first step we will take is to delete from \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) the initial edges that are identical. That is, if \(e_1= f_1\text{,}\) \(e_2= f_2, \dots \text{,}\) \(e_{j}= f_j\text{,}\) and \(e_{j+1}\neq f_{j+1}\) delete the first \(j\) edges of both paths. Once this is done, both paths start at the same vertex, call it \(v_c\text{,}\) and both still end at \(v_b\text{.}\) Now we construct a cycle by starting at \(v_c\) and following what is left of \(p_1\) until we first meet what is left of \(p_2\text{.}\) If this first meeting occurs at vertex \(v_d\text{,}\) then the remainder of the cycle is completed by following the portion of the reverse of \(p_2\) that starts at \(v_d\) and ends at \(v_c\text{.}\)

Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\): Equivalent Conditions for a Graph to be a Tree

Let \(G = (V, E)\) be an undirected graph with no self-loops and \(\lvert V \rvert =n\text{.}\) The following are all equivalent:

- \(G\) is a tree.

- For each pair of distinct vertices in \(V\text{,}\) there exists a unique simple path between them.

- \(G\) is connected, and if \(e\in E\text{,}\) then \((V, E-\{e\})\) is disconnected.

- \(G\) contains no cycles, but by adding one edge, you create a cycle.

- \(G\) is connected and \(\lvert E \rvert =n-1 \text{.}\)

- Proof

-

Proof Strategy. Most of this theorem can be proven by proving the following chain of implications: \((1) \Rightarrow (2)\text{,}\) \((2) \Rightarrow (3)\text{,}\) \((3)\Rightarrow (4)\text{,}\) and \((4) \Rightarrow (1)\text{.}\) Once these implications have been demonstrated, the transitive closure of \(\Rightarrow\) on \({1, 2, 3, 4}\) establishes the equivalence of the first four conditions. The proof that Statement 5 is equivalent to the first four can be done by induction, which we will leave to the reader.

\((1) \Rightarrow (2)\) (Indirect). Assume that \(G\) is a tree and that there exists a pair of vertices between which there is either no path or there are at least two distinct paths. Both of these possibilities contradict the premise that \(G\) is a tree. If no path exists, \(G\) is disconnected, and if two paths exist, a cycle can be obtained by Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\).

\((2) \Rightarrow (3)\text{.}\) We now use Statement 2 as a premise. Since each pair of vertices in \(V\) are connected by exactly one path, \(G\) is connected. Now if we select any edge \(e\) in \(E\text{,}\) it connects two vertices, \(v_1\) and \(v_2\text{.}\) By (2), there is no simple path connecting \(v_1\) to \(v_2\) other than \(e\text{.}\) Therefore, no path at all can exist between \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) in \((V, E - \{e\})\text{.}\) Hence \((V, E - \{e\})\) is disconnected.

\((3)\Rightarrow (4)\text{.}\) Now we will assume that Statement 3 is true. We must show that \(G\) has no cycles and that adding an edge to \(G\) creates a cycle. We will use an indirect proof for this part. Since (4) is a conjunction, by DeMorgan's Law its negation is a disjunction and we must consider two cases. First, suppose that \(G\) has a cycle. Then the deletion of any edge in the cycle keeps the graph connected, which contradicts (3). The second case is that the addition of an edge to \(G\) does not create a cycle. Then there are two distinct paths between the vertices that the new edge connects. By Lemma \(\PageIndex{1}\), a cycle can then be created, which is a contradiction.

\((4) \Rightarrow (1)\) Assume that \(G\) contains no cycles and that the addition of an edge creates a cycle. All that we need to prove to verify that \(G\) is a tree is that \(G\) is connected. If it is not connected, then select any two vertices that are not connected. If we add an edge to connect them, the fact that a cycle is created implies that a second path between the two vertices can be found which is in the original graph, which is a contradiction.

The usual definition of a directed tree is based on whether the associated undirected graph, which is created by “erasing” its directional arrows, is a tree. In Section 10.3 we will introduce the rooted tree, which is a special type of directed tree.

Exercises

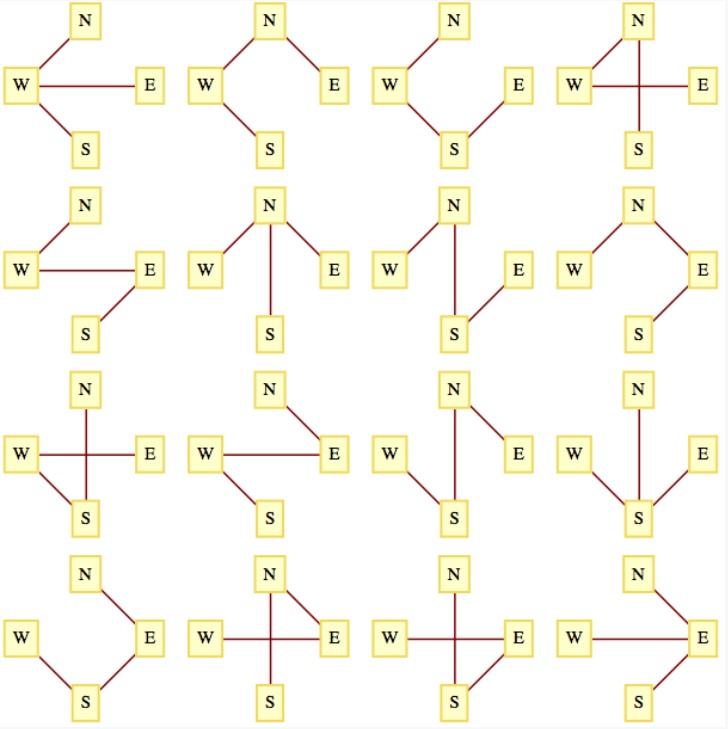

Given the following vertex sets, draw all possible undirected trees that connect them.

- \(\displaystyle V_a= \{\text{right},\text{left}\}\)

- \(\displaystyle V_b = \{+,-,0\}\)

- \(V_c = \{\text{north}, \text{south}, \text{east}, \text{west}\}\text{.}\)

- Answer

-

The number of trees are: (a) 1, (b) 3, and (c) 16. The trees that connect \(V_c\) are:

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Are all trees planar? If they are, can you explain why? If they are not, you should be able to find a nonplanar tree.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Prove that if \(G\) is a simple undirected graph with no self-loops, then \(G\) is a tree if and only if \(G\) is connected and \(\lvert E \rvert = \lvert V \rvert - 1\text{.}\)

- Hint

-

Use induction on \(\lvert E\rvert \text{.}\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

- Prove that if \(G = (V, E)\) is a tree and \(e \in E\text{,}\) then \((V, E - \{e\})\) is a forest of two trees.

- Prove that if \(\left(V_1,E_1\right.\)) and \(\left(V_2,E_2\right)\) are disjoint trees and \(e\) is an edge that connects a vertex in \(V_1\) to a vertex in \(V_2\text{,}\) then \(\left(V_1\cup V_2, E_1\cup E_2\cup \{e\}\right)\) is a tree.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

- Prove that any tree with at least two vertices has at least two vertices of degree 1.

- Prove that if a tree has \(n\) vertices, \(n \geq 4\text{,}\) and is not a path graph, \(P_n\text{,}\) then it has at least three vertices of degree 1.

- Answer

-

- Assume that \((V,E)\) is a tree with \(|V|≥2\), and all but possibly one vertex in \(V\) has degree two or more.

\[\begin{aligned}2|E|=\sum\limits_{v\in V}^{}\text{deg}(v)\geq 2|V|-1 &\Rightarrow |E|\geq |V|-\frac{1}{2} \\ &\Rightarrow |E|\geq |V| \\ &\Rightarrow (V,E)\text{ is not a tree.}\end{aligned}\] - The proof of this part is similar to part a in that we can infer \(2|E|≥2|V|−1\), using the fact that a non-chain tree has at least one vertex of degree three or more.

- Assume that \((V,E)\) is a tree with \(|V|≥2\), and all but possibly one vertex in \(V\) has degree two or more.