16.2: Pythagorean Theorem

- Page ID

- 23683

Here is an analog of the Pythagorean theorems (Theorem 6.2.1 and Theorem 13..1) in spherical geometry.

Let \(\triangle_sABC\) be a spherical triangle with a right angle at \(C\). Set \(a=BC_s\), \(b=CA_s\), and \(c=AB_s\). Then

\(\cos c=\cos a \cdot \cos b.\)

- Proof

-

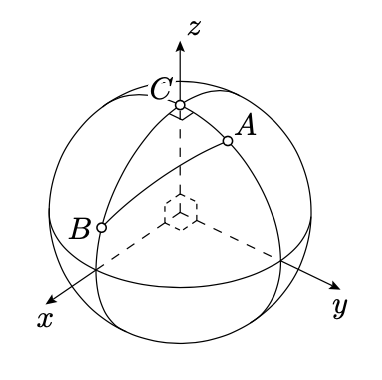

Since the angle at \(C\) is right, we can choose the coordinates in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) so that \(v_C\z=(0,0,1)\), \(v_A\) lies in the \(xz\)-plane, so \(v_A=(x_A,0,z_A)\), and \(v_B\) lies in \(yz\)-plane, so \(v_B=(0,y_B,z_B)\).

Applying, 16.2.3, we get that

\(\begin{aligned} z_A&=\langle v_C,v_A\rangle =\cos b, \\ z_B&=\langle v_C,v_B\rangle =\cos a.\end{aligned}\)

Applying, 16.2.1 and 16.2.3, we get that

\(\begin{aligned} \cos c &=\langle v_A,v_B\rangle= \\ &=x_A\cdot 0+0\cdot y_B+z_A\cdot z_B= \\ &=\cos b\cdot\cos a.\end{aligned}\)

In the proof, we will use the notion of the scalar product which we are about to discuss.

Let \(v_A=(x_A,y_A,z_A)\) and \(v_B=(x_B,y_B,z_B)\) denote the position vectors of points \(A\) and \(B\). The scalar product of the two vectors \(v_A\) and \(v_B\) in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) is defined as

\[\langle v_A,v_B\rangle := x_A\cdot x_B+y_A\cdot y_B+z_A\cdot z_B.\]

Assume both vectors \(v_A\) and \(v_B\) are nonzero; suppose that \(\phi\) denotes the angle measure between them. Then the scalar product can be expressed the following way:

\[\langle v_A,v_B\rangle=|v_A|\cdot|v_B|\cdot\cos\phi, \]

where

\(\begin{aligned} |v_A|&=\sqrt{x_A^2+y_A^2+z_A^2}, & |v_B|&=\sqrt{x_B^2+y_B^2+z_B^2}.\end{aligned}\)

Now, assume that the points \(A\) and \(B\) lie on the unit sphere \(\Sigma\) in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) centered at the origin. In this case \(|v_A|=|v_B|=1\). By 16.2.2 we get that

\[\cos AB_s=\langle v_A,v_B\rangle.\]

AShow that if \(\triangle_s ABC\) is a spherical triangle with a right angle at \(C\), and \(AC_s=BC_s=\dfrac{\pi}{4}\), then \(AB_s=\dfrac{\pi}{3}\).

- Hint

-

Applying the Pythagorean theorem, we get that

\(\cos AB_s = \cos AC_s \cdot \cos BC_s = \dfrac{1}{2}.\)

Therefore, \(AB_s = \dfrac{\pi}{3}.\)

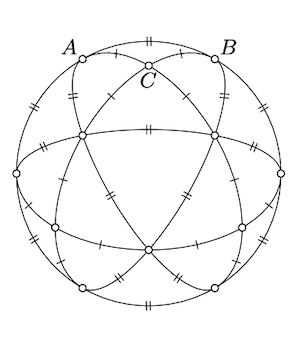

Alternatively, look at the tessellation of a hemisphere on the picture; it is made from 12 copies of \(\triangle_s ABC\) and yet 4 equilateral spherical triangles. From the symmetry of this tessellation, it follows that \([AB]_s\) occupies \(\dfrac{1}{6}\) of the equator; that is, \(AB_s = \dfrac{\pi}{3}\).