12.2: The Eigenvalue-Eigenvector Equation

- Page ID

- 2078

In Section 12, we developed the idea of eigenvalues and eigenvectors in the case of linear transformations \(\Re^{2}\rightarrow \Re^{2}\). In this section, we will develop the idea more generally.

Definition: the Eigenvalue-Eigenvector Equation

For a linear transformation \(L \colon V\rightarrow V\), then \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of \(L\) with \(\textit{eigenvector}\) \(v\neq 0_{V}\) if

\[Lv=\lambda v.\]

This equation says that the direction of \(v\) is invariant (unchanged) under \(L\).

Let's try to understand this equation better in terms of matrices. Let \(V\) be a finite-dimensional vector space and let \(L \colon V\rightarrow V\). If we have a basis for \(V\) we can represent \(L\) by a square matrix \(M\) and find eigenvalues \(\lambda\) and associated eigenvectors \(v\) by solving the homogeneous system

\[(M-\lambda I)v=0.\]

This system has non-zero solutions if and only if the matrix

\[M-\lambda I\]

is singular, and so we require that

\[\det (\lambda I-M) = 0.\]

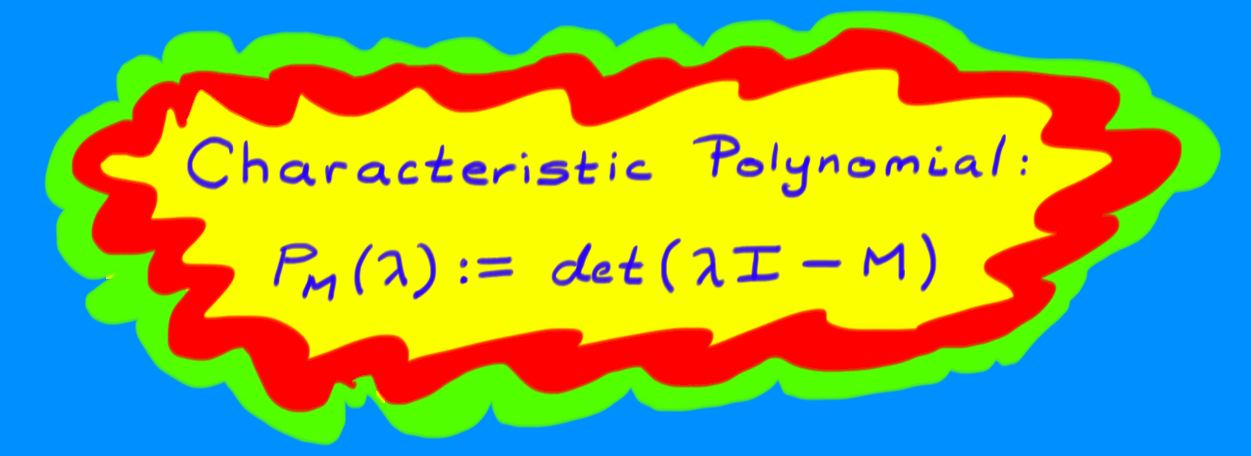

The left hand side of this equation is a polynomial in the variable \(\lambda\) called the \(\textit{characteristic polynomial}\) \(P_{M}(\lambda)\) of \(M\). For an \(n\times n\) matrix, the characteristic polynomial has degree \(n\). Then

\[P_{M}(\lambda) = \lambda^{n}+c_{1}\lambda^{n-1}+\cdots+c_{n}.\]

Notice that \(P_{M}(0)=\det (-M)=(-1)^{n}\det M\).

The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra states that any polynomial can be factored into a product of first order polynomials over \(C\). Then there exists a collection of \(n\) complex numbers \(\lambda_{i}\) (possibly with repetition) such that

\[P_{M}(\lambda)=(\lambda-\lambda_{1})(\lambda-\lambda_{2})\cdots(\lambda-\lambda_{n})\: \Longrightarrow\: P_{M}(\lambda_{i})=0\]

The eigenvalues \(\lambda_{i}\) of \(M\) are exactly the roots of \(P_{M}(\lambda)\). These eigenvalues could be real or complex or zero, and they need not all be different. The number of times that any given root \(\lambda_{i}\) appears in the collection of eigenvalues is called its \(\textit{multiplicity}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Let \(L\) be the linear transformation \(L \colon \Re^{3}\rightarrow \Re^{3}\) given by

$$L\begin{pmatrix}x\\y\\z\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}2x+y-z\\ x+2y-z\\ -x-y+2z\end{pmatrix}\, .\]

In the standard basis the matrix \(M\) representing \(L\) has columns \(Le_{i}\) for each \(i\), so:

\[

\begin{pmatrix}x\\y\\z\end{pmatrix} \stackrel{L}{\mapsto}

\begin{pmatrix}

2 & 1 & -1\\

1 & 2 & -1\\

-1 & -1 & 2\\

\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}x\\y\\z\end{pmatrix}.

\]

Then the characteristic polynomial of \(L\) is

\begin{eqnarray*}

P_{M}(\lambda)&=&\det \begin{pmatrix}

{\lambda - 2} &{ -1} & {1}\\

{-1} &{ \lambda - 2} & {1}\\

{1} & {1} & {\lambda - 2}\\

\end{pmatrix}\\[4pt]

&=& (\lambda - 2)[ (\lambda - 2)^{2}-1 ] +

[-(\lambda - 2)-1 ] +

[-(\lambda - 2)-1] \\[4pt]

&=& (\lambda - 1)^{2}(\lambda - 4)\, .

\end{eqnarray*}

So \(L\) has eigenvalues \(\lambda_{1}=1\) (with multiplicity \(2\)), and \(\lambda_{2}=4\) (with multiplicity \(1\)).

To find the eigenvectors associated to each eigenvalue, we solve the homogeneous system \((M-\lambda_{i}I)X=0\) for each \(i\).

1. \([\underline{\lambda=4:}]\) We set up the augmented matrix for the linear system:

\[\left(\begin{array}{rrrr} -2 & 1 &-1 & 0 \\1 & -2 &-1 & 0 \\-1 & -1 &-2 & 0 \end{array}\right) \sim \left(\begin{array}{rrrr} 1 & -2 &-1 & 0 \\0 & -3 &-3 & 0 \\0 & -3 &-3 & 0 \end{array}\right) \sim \left(\begin{array}{rrrr} 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\0 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array}\right)\]

So we see that \(z=z=:t\), \(y=-t\), and \(x=-t\) gives a formula for eigenvectors in terms of the free parameter \(t\). Any such eigenvector is of the form \(t\begin{pmatrix}-1\\-1\\1\end{pmatrix}\); thus \(L\) leaves a line through the origin invariant.

2. \([\underline{\lambda=1:}]\) Again we set up an augmented matrix and find the solution set:

\[\left(\begin{array}{rrrr} 1 & 1 &-1 & 0 \\1 & 1 &-1 & 0 \\-1 & -1 & 1 & 0 \end{array}\right) \sim \left(\begin{array}{rrrr} 1 & 1 & -1 & 0 \\0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array}\right)\]

Then the solution set has two free parameters, \(s\) and \(t\), such that \(z=z=:t\), \(y=y=:s\), and \(x=-s+t\). Thus \(L\) leaves invariant the set:

\[ \left\{ s\begin{pmatrix}-1\\1\\0\end{pmatrix}+t\begin{pmatrix}1\\0\\1\end{pmatrix} \middle| s,t\in \Re \right\}.\]

This set is a plane through the origin. So the multiplicity two eigenvalue has two independent eigenvectors, \(\begin{pmatrix}-1\\1\\0\end{pmatrix}\) and \(\begin{pmatrix}1\\0\\1\end{pmatrix}\) that determine an invariant plane.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Let \(V\) be the vector space of smooth \((\textit{i.e.} infinitely ~differentiable)\) functions \(f \colon \Re\rightarrow \Re\). Then the derivative is a linear operator \(\frac{d}{dx} \colon V\rightarrow V\). What are the eigenvectors of the derivative? In this case, we don't have a matrix to work with, so we have to make do. A function \(f\) is an eigenvector of \(\frac{d}{dx}\) if there exists some number \(\lambda\) such that \(\frac{d}{dx}f=\lambda f\). An obvious candidate is the exponential function, \(e^{\lambda x}\); indeed, \(\frac{d}{dx} e^{\lambda x} = \lambda e^{\lambda x}\).

The operator \(\frac{d}{dx}\) has an eigenvector \(e^{\lambda x}\) for every \(\lambda \in \Re\).