4.1: Graphing with the TI-84

- Page ID

- 48968

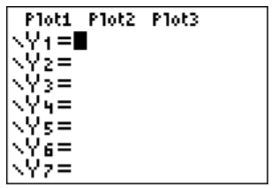

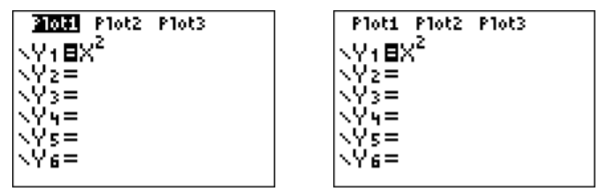

We now use the TI-84 to graph functions such as the functions discussed in the previous chapters. We start by graphing the very well-known function \(y=x^2\), which is of course a parabola. To graph \(y=x^2\), we first have to enter the function. Press the \(\boxed {y =}\) key to get to the function menu:

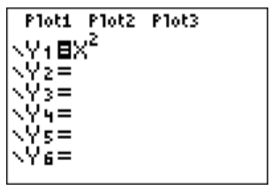

In the first line, enter the function \(y=x^2\) by pressing the buttons \(\boxed {X,T,\theta ,n} \) for the variable “\(x\),” and then press the button \(\boxed {x^2}\). We obtain

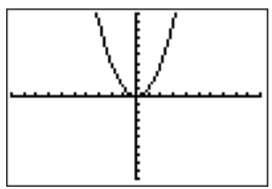

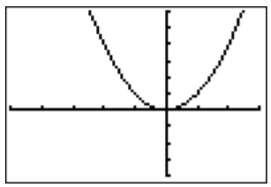

We now go to the graphing window by pressing the \(\boxed {\text{graph}}\) key. We obtain:

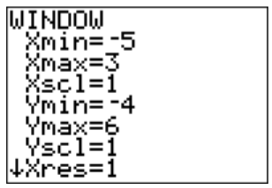

Here, the viewing window is displayed in its initial and standard setting between \(-10\) and \(10\) on the \(x\)-axis, and between \(-10\) and \(10\) on the \(y\)-axis. These settings may be changed by pressing the \(\boxed {\text{window}}\) or the \(\boxed {\text{zoom}}\) keys. First, pressing \(\boxed {\text{window}}\), we may change the scale by setting Xmin, Xmax, Ymin and Ymax to some new values using \(\boxed {\bigtriangledown }\) and \(\boxed {\text{enter}}\):

Note, that negative numbers have to be entered via \(\boxed {(-)}\) and not using \(\boxed {-}\).

The difference between \(\boxed {(-)}\) and \(\boxed {-}\) is that \(\boxed {(-)}\) is used to denote negative numbers (such as \(-10\)), whereas \(\boxed {-}\) is used to subtract two numbers (such as \(7-3\)).

A source for a common error occurs when the “Plot1" item in the function menu is highlighted. When graphing a function as above, always make sure that none of the “plots” are highlighted.

After changing the minimum and maximum \(x\)- and \(y\)-values of our window, we can see the result after pressing \(\boxed {\text{graph}}\) again:

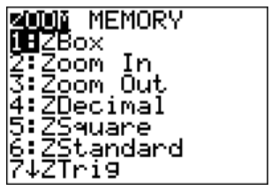

We may zoom in or out or put the setting back to the standard viewing size by pressing the \(\boxed {\text{zoom}}\) key:

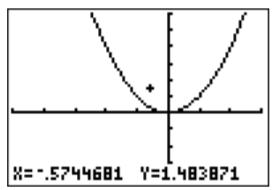

We may zoom in by pressing \(\boxed {2}\), then choose a center in the graph where we want to focus (via the\(\boxed {\bigtriangleup }\), \(\boxed {\bigtriangledown }\), \(\boxed {\triangleleft }\), \(\boxed {\triangleright }\) keys), and confirm this with \(\boxed {\text{enter}}\):

Similarly, we may also zoom out (pressing using \(\boxed {3}\) in the zoom menu and choosing a center). Finally we can recover the original setting by using ZStandard in the zoom menu (press \(\boxed {6}\)).

We can graph more than one function in the same window, which we show next.

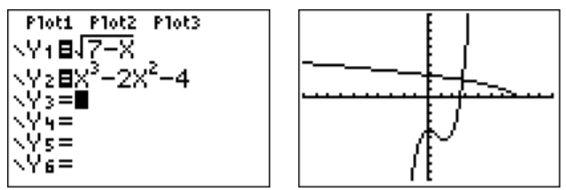

Graph the equations \(y=\sqrt{7-x}\) and \(y=x^3-2x^2-4\) in the same window.

Solution

Enter the functions as Y1 and Y2 after pressing \(\boxed {y=}\).

The graphs of both functions appear together in the graphing window:

Here, the square root symbol “\(\sqrt{\,\,}\)” is obtained using \(\boxed {2\text{nd}}\) and \(\boxed {x^2}\), and the third power via \(\boxed {\wedge}\) and \(\boxed {3}\) (followed by \(\boxed {\triangleright }\) to continue entering the function on the base line).

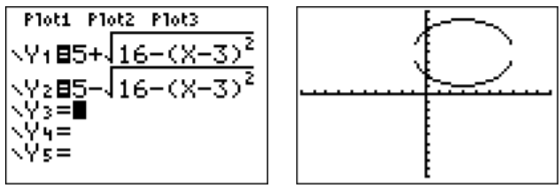

Graph the relation \((x-3)^2+(y-5)^2=16\).

Solution

Since the above expression is not solved for \(y\), we cannot simply plug this into the calculator. Instead, we have to solve for \(y\) first.

\[\begin{aligned} (x-3)^2+(y-5)^2=16 &\implies & (y-5)^2=16-(x-3)^2 \\ &\implies & y-5=\pm \sqrt{16-(x-3)^2} \\ &\implies & y=5\pm \sqrt{16-(x-3)^2} \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Note, that there are two functions that we need to graph: \(y=5+\sqrt{16-(x-3)^2}\) and \(y=5-\sqrt{16-(x-3)^2}\). Entering these as Y1 and Y2 in the calculator gives the following function menu and graphing window:

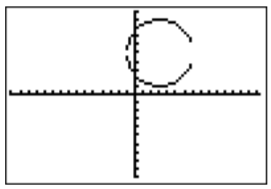

The graph displays a circle of radius \(4\) with a center at \((3,5)\). However, due to the current scaling, the graph looks more like an ellipse instead of a circle. We can remedy this by using the “zoom square” function; press \(\boxed {\text{zoom}}\) \(\boxed {5}\). This adjusts the axis to the same scale in the \(x\)- and the \(y\)-direction. We obtain the following graph:

We recall that the equation \((x-h)^2+(y-k)^2=r^2\) always forms a circle in the plane. Indeed, this equation describes a circle with center \(C(h,k)\) and radius \(r\).