2.20: Adding, Subtracting, and Multiplying Radical Expressions

- Page ID

- 95224

Adding and Subtracting Radical Expressions

Adding radical expressions with the same index and the same radicand is just like adding like terms. We call radicals with the same index and the same radicand like radicals to remind us they work the same as like terms.

Like radicals are radical expressions with the same index and the same radicand.

We add and subtract like radicals in the same way we add and subtract like terms. We know that \(3x+8x\) is \(11x\).Similarly we add \(3 \sqrt{x}+8 \sqrt{x}\) and the result is \(11 \sqrt{x}\).

Think about adding like terms with variables as you do the next few examples. When you have like radicals, you just add or subtract the coefficients. When the radicals are not like, you cannot combine the terms.

Simplify:

- \(2 \sqrt{2}-7 \sqrt{2}\)

- \(5 \sqrt[3]{y}+4 \sqrt[3]{y}\)

- \(7 \sqrt[4]{x}-2 \sqrt[4]{y}\)

Solution:

a.

\(2 \sqrt{2}-7 \sqrt{2}\)

Since the radicals are like, we subtract the coefficients.

\(-5 \sqrt{2}\)

b.

\(5 \sqrt[3]{y}+4 \sqrt[3]{y}\)

Since the radicals are like, we add the coefficients.

\(9 \sqrt[3]{y}\)

c.

\(7 \sqrt[4]{x}-2 \sqrt[4]{y}\)

The indices are the same but the radicals are different. These are not like radicals. Since the radicals are not like, we cannot subtract them.

Simplify:

- \(5 \sqrt{3}-9 \sqrt{3}\)

- \(5 \sqrt[3]{y}+3 \sqrt[3]{y}\)

- \(5 \sqrt[4]{m}-2 \sqrt[3]{m}\)

- Answer

-

- \(-4 \sqrt{3}\)

- \(8 \sqrt[3]{y}\)

- \(5 \sqrt[4]{m}-2 \sqrt[3]{m}\)

For radicals to be like, they must have the same index and radicand. When the radicands contain more than one variable, as long as all the variables and their exponents are identical, the radicands are the same.

Simplify:

- \(2 \sqrt{5 n}-6 \sqrt{5 n}+4 \sqrt{5 n}\)

- \(\sqrt[4]{3 x y}+5 \sqrt[4]{3 x y}-4 \sqrt[4]{3 x y}\)

Solution:

a.

\(2 \sqrt{5 n}-6 \sqrt{5 n}+4 \sqrt{5 n}\)

Since the radicals are like, we combine them.

\(0 \sqrt{5 n}\)

Simplify.

\(0\)

b.

\(\sqrt[4]{3 x y}+5 \sqrt[4]{3 x y}-4 \sqrt[4]{3 x y}\)

Since the radicals are like, we combine them.

\(2 \sqrt[4]{3 x y}\)

Simplify:

- \(4 \sqrt{3 y}-7 \sqrt{3 y}+2 \sqrt{3 y}\)

- \(6 \sqrt[3]{7 m n}+\sqrt[3]{7 m n}-4 \sqrt[3]{7 m n}\)

- Answer

-

- \(-\sqrt{3 y}\)

- \(3 \sqrt[3]{7 m n}\)

Remember that we always simplify radicals by removing the largest factor from the radicand that is a power of the index. Once each radical is simplified, we can then decide if they are like radicals.

Simplify:

- \(\sqrt{20}+3 \sqrt{5}\)

- \(\sqrt[3]{24}-\sqrt[3]{375}\)

- \(\frac{1}{2} \sqrt[4]{48}-\frac{2}{3} \sqrt[4]{243}\)

Solution:

a.

\(\sqrt{20}+3 \sqrt{5}\)

Simplify the radicals, when possible.

\(\sqrt{4} \cdot \sqrt{5}+3 \sqrt{5}\)

\(2 \sqrt{5}+3 \sqrt{5}\)

Combine the like radicals.

\(5 \sqrt{5}\)

b.

\(\sqrt[3]{24}-\sqrt[3]{375}\)

Simplify the radicals.

\(\sqrt[3]{8} \cdot \sqrt[3]{3}-\sqrt[3]{125} \cdot \sqrt[3]{3}\)

\(2 \sqrt[3]{3}-5 \sqrt[3]{3}\)

Combine the like radicals.

\(-3 \sqrt[3]{3}\)

c.

\(\frac{1}{2} \sqrt[4]{48}-\frac{2}{3} \sqrt[4]{243}\)

Simplify the radicals.

\(\frac{1}{2} \sqrt[4]{16} \cdot \sqrt[4]{3}-\frac{2}{3} \sqrt[4]{81} \cdot \sqrt[4]{3}\)

\(\frac{1}{2} \cdot 2 \cdot \sqrt[4]{3}-\frac{2}{3} \cdot 3 \cdot \sqrt[4]{3}\)

\(\sqrt[4]{3}-2 \sqrt[4]{3}\)

Combine the like radicals.

\(-\sqrt[4]{3}\)

Simplify:

- \(\sqrt{27}+4 \sqrt{3}\)

- \(4 \sqrt[3]{5}-7 \sqrt[3]{40}\)

- \(\frac{1}{2} \sqrt[3]{128}-\frac{5}{3} \sqrt[3]{54}\)

- Answer

-

- \(7 \sqrt{3}\)

- \(-10 \sqrt[3]{5}\)

- \(-3 \sqrt[3]{2}\)

In the next example, we will remove both constant and variable factors from the radicals. Now that we have practiced taking both the even and odd roots of variables, it is common practice at this point for us to assume all variables are greater than or equal to zero so that absolute values are not needed. We will use this assumption thoughout the rest of this chapter.

Simplify:

- \(9 \sqrt{50 m^{2}}-6 \sqrt{48 m^{2}}\)

- \(\sqrt[3]{54 n^{5}}-\sqrt[3]{16 n^{5}}\)

Solution:

a.

\(9 \sqrt{50 m^{2}}-6 \sqrt{48 m^{2}}\)

Simplify the radicals.

\(9 \sqrt{25 m^{2}} \cdot \sqrt{2}-6 \sqrt{16 m^{2}} \cdot \sqrt{3}\)

\(9 \cdot 5 m \cdot \sqrt{2}-6 \cdot 4 m \cdot \sqrt{3}\)

\(45 m \sqrt{2}-24 m \sqrt{3}\)

The radicals are not like and so cannot be combined.

b.

\(\sqrt[3]{54 n^{5}}-\sqrt[3]{16 n^{5}}\)

Simplify the radicals.

\(\sqrt[3]{27 n^{3}} \cdot \sqrt[3]{2 n^{2}}-\sqrt[3]{8 n^{3}} \cdot \sqrt[3]{2 n^{2}}\)

\(3 n \sqrt[3]{2 n^{2}}-2 n \sqrt[3]{2 n^{2}}\)

Combine the like radicals.

\(n \sqrt[3]{2 n^{2}}\)

Simplify:

- \(\sqrt{27 p^{3}}-\sqrt{48 p^{3}}\)

- \(\sqrt[3]{256 y^{5}}-\sqrt[3]{32 n^{5}}\)

- Answer

-

- \(-p \sqrt{3 p}\)

- \(4 y \sqrt[3]{4 y^{2}}-2 n \sqrt[3]{4 n^{2}}\)

Multiplying Radical Expressions

We have used the Product Property of Roots to simplify square roots by removing the perfect square factors. We can use the Product Property of Roots ‘in reverse’ to multiply square roots. Remember, we assume all variables are greater than or equal to zero.

We will rewrite the Product Property of Roots so we see both ways together.

For any real numbers, \(\sqrt[n]{a}\) and \(\sqrt[n]{b}\), and for any integer \(n≥2\)

\(\sqrt[n]{a b}=\sqrt[n]{a} \cdot \sqrt[n]{b} \quad \text { and } \quad \sqrt[n]{a} \cdot \sqrt[n]{b}=\sqrt[n]{a b}\)

When we multiply two radicals they must have the same index. Once we multiply the radicals, we then look for factors that are a power of the index and simplify the radical whenever possible.

Multiplying radicals with coefficients is much like multiplying variables with coefficients. To multiply \(4x⋅3y\) we multiply the coefficients together and then the variables. The result is \(12xy\). Keep this in mind as you do these examples.

Simplify:

- \((6 \sqrt{2})(3 \sqrt{10})\)

- \((-5 \sqrt[3]{4})(-4 \sqrt[3]{6})\)

Solution:

a.

\((6 \sqrt{2})(3 \sqrt{10})\)

Multiply using the Product Property.

\(18\sqrt{20}\)

Simplify the radical.

\(18 \sqrt{4} \cdot \sqrt{5}\)

Simplify.

\(18 \cdot 2 \cdot \sqrt{5}\)

\(36 \sqrt{5}\)

b.

\((-5 \sqrt[3]{4})(-4 \sqrt[3]{6})\)

Multiply using the Product Property.

\(20 \sqrt[3]{24}\)

Simplify the radical.

\(20 \sqrt[3]{8} \cdot \sqrt[3]{3}\)

Simplify.

\(20 \cdot 2 \cdot \sqrt[3]{3}\)

\(40 \sqrt[3]{3}\)

Simplify:

- \((3 \sqrt{2})(2 \sqrt{30})\)

- \((2 \sqrt[3]{18})(-3 \sqrt[3]{6})\)

- Answer

-

- \(12 \sqrt{15}\)

- \(-18 \sqrt[3]{2}\)

We follow the same procedures when there are variables in the radicands.

Simplify:

- \(\left(10 \sqrt{6 p^{3}}\right)(4 \sqrt{3 p})\)

- \(\left(2 \sqrt[4]{20 y^{2}}\right)\left(3 \sqrt[4]{28 y^{3}}\right)\)

Solution:

a.

\(\left(10 \sqrt{6 p^{3}}\right)(4 \sqrt{3 p})\)

Multiply.

\(40 \sqrt{18 p^{4}}\)

Simplify the radical.

\(40 \sqrt{9 p^{4}} \cdot \sqrt{2}\)

Simplify.

\(40 \cdot 3 p^{2} \cdot \sqrt{3}\)

\(120 p^{2} \sqrt{3}\)

b. When the radicands involve large numbers, it is often advantageous to factor them in order to find the perfect powers.

\(\left(2 \sqrt[4]{20 y^{2}}\right)\left(3 \sqrt[4]{28 y^{3}}\right)\)

Multiply.

\(6 \sqrt[4]{4 \cdot 5 \cdot 4 \cdot 7 y^{5}}\)

Simplify the radical.

\(6 \sqrt[4]{16 y^{4}} \cdot \sqrt[4]{35 y}\)

Simplify.

\(6 \cdot 2 y \sqrt[4]{35 y}\)

Multiply.

\(12 y \sqrt[4]{35 y}\)

Simplify:

- \(\left(6 \sqrt{6 x^{2}}\right)\left(8 \sqrt{30 x^{4}}\right)\)

- \(\left(-4 \sqrt[4]{12 y^{3}}\right)\left(-\sqrt[4]{8 y^{3}}\right)\)

- Answer

-

- \(36 x^{3} \sqrt{5}\)

- \(8 y \sqrt[4]{3 y^{2}}\)

Using Polynomial Multiplication to Multiply Radical Expressions

In the next a few examples, we will use the Distributive Property to multiply expressions with radicals. First we will distribute and then simplify the radicals when possible.

Simplify:

- \(\sqrt{6}(\sqrt{2}+\sqrt{18})\)

- \(\sqrt[3]{9}(5-\sqrt[3]{18})\)

Solution:

a.

\(\sqrt{6}(\sqrt{2}+\sqrt{18})\)

Multiply.

\(\sqrt{12}+\sqrt{108}\)

Simplify.

\(\sqrt{4} \cdot \sqrt{3}+\sqrt{36} \cdot \sqrt{3}\)

Simplify.

\(2 \sqrt{3}+6 \sqrt{3}\)

Combine like radicals.

\(8\sqrt{3}\)

b.

\(\sqrt[3]{9}(5-\sqrt[3]{18})\)

Distribute.

\(5 \sqrt[3]{9}-\sqrt[3]{162}\)

Simplify.

\(5 \sqrt[3]{9}-\sqrt[3]{27} \cdot \sqrt[3]{6}\)

Simplify.

\(5 \sqrt[3]{9}-3 \sqrt[3]{6}\)

Simplify:

- \(\sqrt{8}(2-5 \sqrt{8})\)

- \(\sqrt[3]{3}(-\sqrt[3]{9}-\sqrt[3]{6})\)

- Answer

-

- \(-40+4 \sqrt{2}\)

- \(-3-\sqrt[3]{18}\)

When we worked with polynomials, we multiplied binomials by binomials. Remember, this gave us four products before we combined any like terms. To be sure to get all four products, we organized our work—usually by the FOIL method.

Simplify:

- \((3-2 \sqrt{7})(4-2 \sqrt{7})\)

- \((\sqrt[3]{x}-2)(\sqrt[3]{x}+4)\)

Solution:

a.

\((3-2 \sqrt{7})(4-2 \sqrt{7})\)

Multiply.

\(12-6 \sqrt{7}-8 \sqrt{7}+4 \cdot 7\)

Simplify.

\(12-6 \sqrt{7}-8 \sqrt{7}+28\)

Combine like terms.

\(40-14 \sqrt{7}\)

b.

\((\sqrt[3]{x}-2)(\sqrt[3]{x}+4)\)

Multiply.

\(\sqrt[3]{x^{2}}+4 \sqrt[3]{x}-2 \sqrt[3]{x}-8\)

Combine like terms.

\(\sqrt[3]{x^{2}}+2 \sqrt[3]{x}-8\)

Simplify:

- \((2-3 \sqrt{11})(4-\sqrt{11})\)

- \((\sqrt[3]{x}+1)(\sqrt[3]{x}+3)\)

- Answer

-

- \(41-14 \sqrt{11}\)

- \(\sqrt[3]{x^{2}}+4 \sqrt[3]{x}+3\)

Simplify: \((3 \sqrt{2}-\sqrt{5})(\sqrt{2}+4 \sqrt{5})\)

Solution:

\((3 \sqrt{2}-\sqrt{5})(\sqrt{2}+4 \sqrt{5})\)

Multiply.

\(3 \cdot 2+12 \sqrt{10}-\sqrt{10}-4 \cdot 5\)

Simplify.

\(6+12 \sqrt{10}-\sqrt{10}-20\)

Combine like terms.

\(-14+11 \sqrt{10}\)

Simplify: \((\sqrt{6}-3 \sqrt{8})(2 \sqrt{6}+\sqrt{8})\)

- Answer

-

\(-12-20 \sqrt{3}\)

Recognizing some special products made our work easier when we multiplied binomials earlier. This is true when we multiply radicals, too. The special product formulas we used are shown here.

Special Products

Binomial Squares

\(\begin{array}{l}{(a+b)^{2}=a^{2}+2 a b+b^{2}} \\ {(a-b)^{2}=a^{2}-2 a b+b^{2}}\end{array}\)

Product of Conjugates

\((a+b)(a-b)=a^{2}-b^{2}\)

We will use the special product formulas in the next few examples. We will start with the Product of Binomial Squares Pattern.

Simplify:

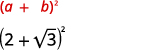

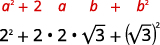

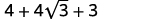

- \((2+\sqrt{3})^{2}\)

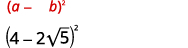

- \((4-2 \sqrt{5})^{2}\)

Solution:

a.

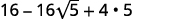

|

|

| Multiply using the Product of Binomial Squares Pattern. |  |

| Simplify. |  |

| Combine like terms. |  |

b.

|

|

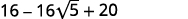

| Multiple, using the Product of Binomial Squares Pattern. |  |

| Simplify. |  |

|

|

| Combine like terms. |  |

Simplify:

- \((10+\sqrt{2})^{2}\)

- \((9-2 \sqrt{10})^{2}\)

- Answer

-

- \(102+20 \sqrt{2}\)

- \(121-36 \sqrt{10}\)

In the next example, we will use the Product of Conjugates Pattern. Notice that the final product has no radical.

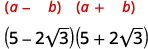

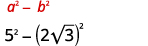

Simplify: \((5-2 \sqrt{3})(5+2 \sqrt{3})\)

Solution:

|

|

| Multiply using the Product of Conjugates Pattern. |  |

| Simplify. |  |

|

Simplify: \((3-2 \sqrt{5})(3+2 \sqrt{5})\)

- Answer

-

\(-11\)