4.2: 2-D Geometry

- Page ID

- 4888

Two-dimensional figures

Definition:

Vertices (pl.) or vertex (sg.): a point or corner which joins two edges of a shape.

Edges: Line which describes one of the outer borders of a shape.

A curve is called a closed curve if we can trace the figure in such a way that our starting point and ending point are the same.

A simple closed curve is a curve that we can trace without going over any point more than once while starting point and ending point are the same.

Polygons

A polygon is a closed, 2-dimensional shape, with edges(sides) being straight lines. The word “polygon” is derived from Greek for “many angles”. The names of the polygons are taken from the Greek number prefixes followed by –gon, with only a couple exceptions.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

3-tri 4-tetra 5-penta 6-hexa 7-hepta 8-octa 9-ennia or nona 10-deca

Definitions:

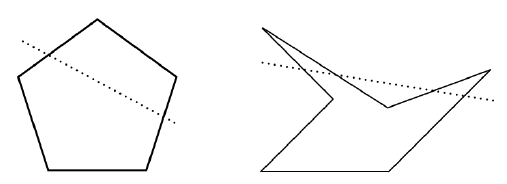

Convex polygons are polygons which, if a line is drawn across them at any point, only two edges will be intersected by the line.

Concave polygons are those in which more than two edges are intersected by a line drawn across the shape.

A polygon is considered to be regular if all of its sides have the same measure. By definition, this also implies that all of the polygon's internal angles will be the same.

A diagonal is a line that joins any two vertices of a shape that are not adjacent to each other.

Two polygons are Congruent if they are identical in size and shape.

- Interior angles of a polygon are the angles between two adjacent sides on the inside of the polygon

- Exterior angles of a polygon are the angles between two adjacent sides on the outside of the polygon

- Central angles are angles between two points on a polygon, measured from the center of the polygon. In circles, this measure is given in radians or degrees.

The center of a regular polygon is a point that is the same distance (equidistant) from all of its vertices. An irregular polygon will not have a center.

The radius of a circle is given by the distance from the centre to the edge.

Regular Polygons

Properties:

A regular polygon's apothem is a line that is drawn from its center to the midpoint of one of its faces

A regular polygon's radius is a line that is drawn from its center to one of its vertices

The perimeter of a shape is the sum of the length of all its faces

The area of a polygon is the measure of its surface area, given in square units such as cm2.

Triangles

A triangle is a polygon with three edges and three vertices and can be defined by a side and two angles. This means that if we know the length of one side and the measure of two angles in a triangle, we can know the measures of all three sides and angles.

Definition:

- Equilateral triangle: A triangle with all sides equal in length.

- Isosceles triangle: A triangle with two sides equal in length.

- Scalene triangle: A triangle with no sides equal in length.

- Right triangle: A triangle with one interior angle that measures 90°.

- Acute-angled triangle: All angles are acute (between 0° and 90°).

- Right-angled triangle: One angle is a right angle (90°).

- Obtuse-angled triangle: One angle is obtuse (between 90° and 180°).

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Classify Triangles

Complete the following table by sketching a triangle, if possible. Otherwise, justify your answer.

|

Isosceles Triangle |

Equilateral Triangle |

Scalene Triangle |

|

|

Acute angled |

|||

|

Obtuse-angled |

|||

|

Right-angled |

Would you be able to sketch all of the above triangles inside a rectangle? Here is an Euler diagram of types of triangles:

Special properties of triangles

Definition:

- Angle Bisector: A line that bisects an angle of a triangle.

- Median: A line segment that connects a vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side.

- Altitude: A perpendicular line segment that connects a vertex to the side opposite to that vertex.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Proof - The Sum of Interior Angles of Any Triangle

The sum of the interior angles of any triangle is 180°:

Lines \(AB\) and \(CD\) are parallel.

By the alternate interior angles property, \(\measuredangle AEC\) and \(\measuredangle ECD\) are equivalent.

By the alternate interior angles property, \(\measuredangle BED\) and \(\measuredangle EDC\) are also equivalent.

Since \(\measuredangle AEC + \measuredangle CED + \measuredangle BED = 180°,\)

Then \(\measuredangle ECD + \measuredangle CED + \measuredangle EDC = 180°\).

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Proof - \(a^2 + b^2 = c^2\), or the Pythagorean Theorem

Method 1: Let us draw two squares made by using four right triangles with sides \(A, \, B, \, C\), where \(A\) is the vertical side, \(B\) is the horizontal side, and \(C\) is the hypotenuse:

Since both squares are the same size, we can say that their areas are equivalent.

Both squares also contain four right triangles.

When we remove the triangles from both squares, we are left with \(c^2\) on the left, and \(a^2 + b^2\) on the right.

Remember, we have two squares of equal area, and we removed the same quantity of area from each.

So: \(a^2 + b^2 = c^2\).

Method 2: President Garfield method

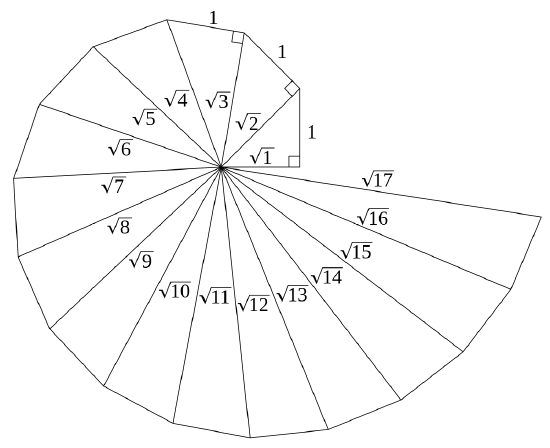

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\): \(\sqrt{2}\) is Irrational

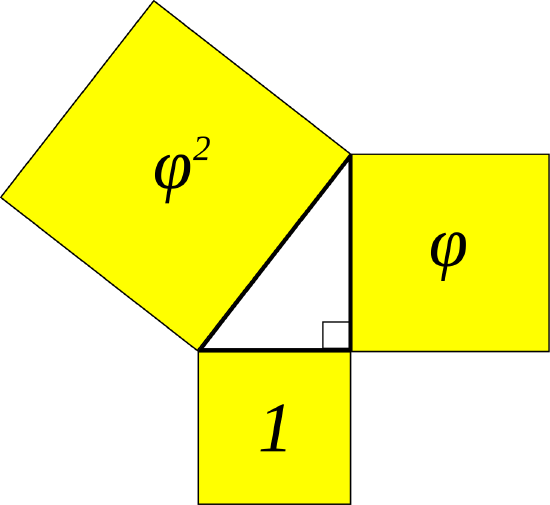

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\): Kepler Triangle

A Kepler Triangle is a right angle triangle with sides \( 1, \sqrt{\phi}, \phi \), where \( \phi \) is the golden ratio.

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\):

Triangle inequality

![By WhiteTimberwolf, Brews ohare (PNG version) (PNG version) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/77683/768px-Triangle_inequality.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=274&height=264)

\(x+y \geq z\).

The sum of the lengths of two sides of any triangle is always greater than or equal to the length of the third side.

Definition:

Triangles are said to be similar triangles if their internal angles are the same, but their sides are different sizes. The sides or similar triangles are in relative proportion: the ratio by which one is bigger or smaller than the other is the same for all sides.

Triangles are congruent if both their sides and their angles are the same.

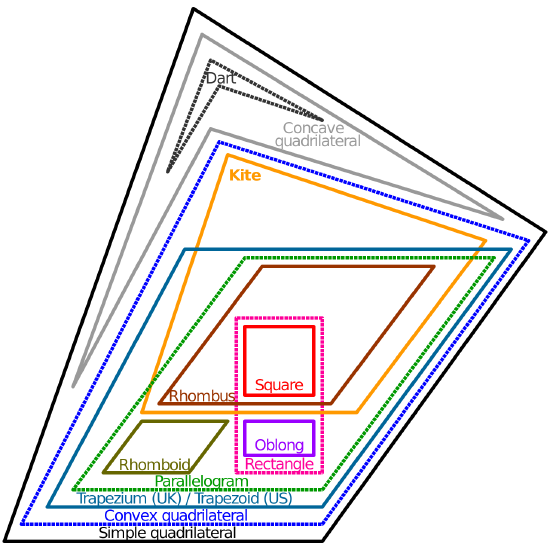

Quadrilaterals

Quadrilaterals are polygons with four edges and four vertices.

- A kite is a quadrilateral with adjacent pairs of sides that are equal.

- A trapezoid is a quadrilateral with one pair of parallel sides.

- A parallelogram is a quadrilateral with opposite sides that are parallel and equal.

- A rhombus is a parallelogram that has all four sides equal.

- A rectangle has four right angles, and thus the sides are parallel and equal in pairs (a quadrilateral with 4 square corners).

- A square has four right angles and four equal sides. (A quadrilateral with 4 square corners and 4 equal sides. Thus, a square is a special type of rectangle!)

Here is an Euler diagram of types of quadrilaterals:

Thinking Out Loud:

Draw a quadrilateral. Find the midpoint of each side (paper folding might help). Connect the midpoints of the sides which have a common vertex. What shape have you created? Is this true for any quadrilateral?Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Proof - The sum of the interior angles of a quadrilateral is \(360^\circ\)

First, let's draw a quadrilateral:

Then, we will make this shape into an aggregate of shapes we know more about: triangles.

As we can see, a quadrilateral is made of two triangles. Since we know that the sum of the internal angles of each triangle is \(180^\circ\), we can add those two together to find that the sum of the internal angles of a quadrilateral is \(360^\circ\).

Thinking Out Loud:

Does the proof of the interior angles of a quadrilateral hold when the quadrilateral is concave? Why? Why not?

Example \(\PageIndex{8}\):

Express the relationship between a rhombus, square, and rectangle with a Venn diagram.

Pentagrams

Pentagrams are polygons that make a five-pointed star.

Example \(\PageIndex{9}\): Proof: The sum of Vertex Angle of a Pentagram is 180°

Consider the following pentagram:

As we can see, we have determined the interior angles of the black triangle in the general case, using the internal vertex angles from the blue and red triangles.

Since the sum of a triangle's interior angles is 180°,

\(a + b + c + d + e = 180°\).

Other Polygons

The sum of the interior angles of polygons with \(n\) sides are given by the formula \((n - 2)180°\). This can be shown by the fact that, \(n\) sided polygons can be divided into \((n-2)\) triangles.

Example \(\PageIndex{10}\):

Consider a regular decagon: \(n = 10\). What is the sum of its internal angles?

Since the sum of interior angles \(= (n-2)180°\),

Then the sum of a regular decagon's interior angles \(= (10 - 2)180°\)

\(= (8)180°\)

\(= 1440°\)

Similarity

Definition

Polygons with \(n\) sides are similar when they have an equal number of sides that are proportional to each other in the same ratio.

Example \(\PageIndex{8}\):

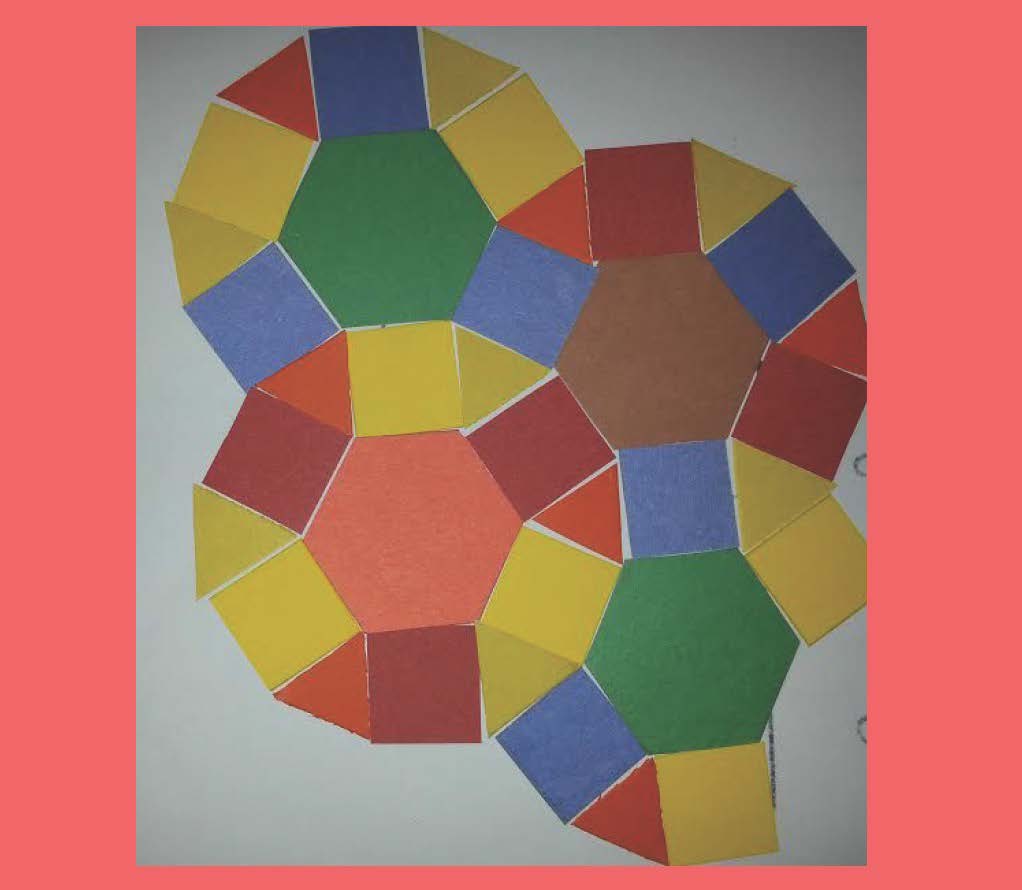

Tessellation

Definition

Tessellation refers to the "tiling" of polygons, as in ceramic tiles or quilts. There are regular tessellation and semi-regular tessellation. A regular tessellation is made up of regular polygons that are all of the same shape and all meet at a common vertex. There are only three types of regular tessellations which are comprised of equilateral triangles, squares and hexagons. The sum of the angles of polygons in regular tessellations forms 360 degrees around each vertex.

Thinking Out Loud:

Given a 2-dimensional stage, which shapes can be tiled? Which can't? Why?

Given a 3-dimensional space, does your answer change? Why or why not?

Definition:

A semi-regular tessellation is made up of two or more types of regular polygon. Polygon arranged in the same cyclic order. There are eight semi-regular tessellations which comprise different combinations of equilateral triangles, squares, hexagons, octagons and dodecagons.

Example \(\PageIndex{11}\): Semi-regular tessellations.

Definition:

Non-Regular Tessellations

Non-Regular Tessellations are those in which there are no restrictions regarding the shapes used or their arrangement around vertices. It is believed there is an infinite number of irregular tessellations.

Curved figures

- Circles

- Semicircle

- Spiral

- Parabola

- Ellipse

- Hyperbola

- Crescent

Circle Geometry

Definitions:

The center of a circle is a point in the circle that is equidistant from all points along the circle's edge. This distance is given by the radius.

The radius of a circle is the distance from the center of the circle to the edge of the circle.

The diameter of a circle is the distance across a circle at its widest point and is twice the circle's radius.

The circumference of a circle is the distance around the circle.

A chord is a line that joins two points on the circumference of a circle.

An arc is a part of the circumference of a circle.

A tangent line meets a circle at one point only.

An inscribed angle is an angle given by two chords that share a common endpoint.

A central angle is an angle describing an arc. This is measured, in circles, in radians.

- The perpendicular line from the center of a circle to a chord bisects the chord.

- \(\pi=\frac{ Circumference}{Diameter}\).

- \(A = \pi r\)\(2\)

- The angle between the tangent at a point, and the radius from the center to that point is \(90^{\circ}\).

- The measure of a central angle is twice as large as the measure of an inscribed angle that cuts the same arc of a circle.

- The angle in a semicircle is a right angle.

Thinking Out Loud:

Can we inscribe regular polygons in a paper cut circle?

Coordinate Geometry

Coordinate geometry applies the Cartesian plane to the geometry we have already learned. Each vertex of a shape now is given an ordered Cartesian pair \((x, \, y)\) to give its position on the grid. To find distances between points, we create the right triangles and apply the Pythagorean Theorem.

Example \(\PageIndex{10}\):

In a general case, point A has coordinates \((x_1, \, y_1)\), and point B has coordinates \((x_2, \, y_2)\). Point C, the point we use to create a right triangle, has coordinates \((x_2, \, y_1)\).

Let \(A (x_1, \, y_1)\), and \( B (x_2, \, y_2)\) be points.

Midpoint CoordinatesThe midpoint coordinates of a line can be thought of as the average of both \(A\) and \(B\) coordinates from both endpoints. So, the formula for the midpoint of a line is:

\(\left( \displaystyle \frac{x_1 + x_2}{2}, \, \displaystyle \frac{y_1 + y_2}{2} \right)\)

Slope of a Line:

The slope of a line, or how much it rises for a given amount of horizontal travel, can be thought of as \(m = \displaystyle \frac{rise}{run} = \displaystyle \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\).

\(\Delta\) is the mathematical symbol indicating the change in a quantity.

Hence the slope of the line \(AB\) is given by \(m = \displaystyle \frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}\).

Distance Formula

The distance between the points \(A\) and \(B\) is given by \(\sqrt{ y_2 - y_1)^2+(x_2 - x_1)^2}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{12}\):

Show, by using coordinate geometry, that the line connecting the midpoints of two sides of a triangle is parallel to the other side.

First, let's draw a picture:

Let us call the midpoints of lines \(AB\) and \(BC\) \(p\) and \(q\), respectively.

Consider the slope of line \(AC\):

\(m\)\(AC\)\(= \displaystyle \frac{y_c - y_a}{x_c - x_a}\)

Consider point \(p\), the midpoint of line \(AC\):

\(p = \left( \displaystyle \frac{x_a + x_b}{2}, \, \displaystyle \frac{y_a + y_b}{2} \right)\)

Consider point \(q\), the midpoint of line \(CB\):

\(q = \left( \displaystyle \frac{x_c + x_b}{2}, \, \displaystyle \frac{y_c + y_b}{2} \right)\)

Consider the slope of line \(pq\)

\(m\)\(pq\)\(= \left( \displaystyle \frac{y_q - y_p}{x_q - x_p} \right)\)

\(= \left( \displaystyle \frac{ \left( \displaystyle \frac{y_c + y_b}{2} \right) - \left( \displaystyle \frac{y_a + y_b}{2} \right)}{ \left(\displaystyle \frac{x_c + x_b}{2} \right) - \left( \displaystyle \frac{x_a + x_b}{2} \right)} \right)\)

\(= \left( \displaystyle \frac{(y_c + y_b) - (y_a + y_b)}{(x_c + x_b) - (x_a + x_b)} \right) \)

\(= \displaystyle \frac{y_c - y_a}{x_c - x_a}\)

Thus, we have shown that \(m\)\(AC\)\(\, = m\)\(pq\). QED.

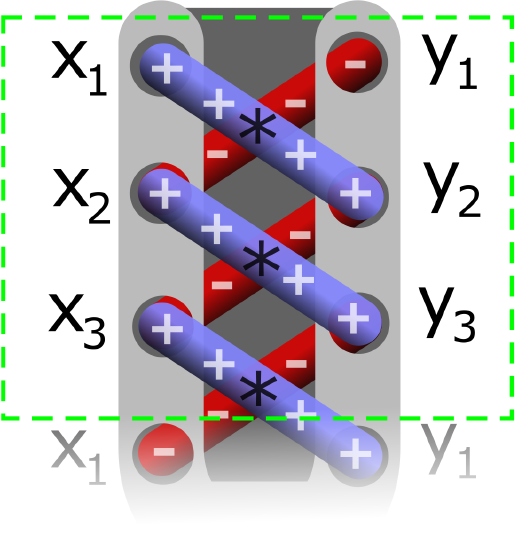

Shoelace formula:

Let \((x_1,y_1), (x_2,y_2), \cdots, (x_n,y_n)\) be coordinates of the vertices of a polygon with \(n\) sides. Then the area of the polygon given by \[A= \frac{1}{2} |x_1y_2+x_2y_3+\cdots+ x_ny_1-x_2y_1-x_3y_2-\cdots-x_1y_n|\]

Notice the blue laces and red laces in the attached figure.

Example \(\PageIndex{13}\):

Find the area of the triangle with vertices \((1,2),(2,3)\) and \((3,5)\). Make a shoelace diagram first!

By using the shoelace formula,

The area \(A= \frac{1}{2} |(1)(3)+(2)(5)+(3)(2)-(2)(2)-(3)(3)-(1)(5)|= \frac{1}{2}\).

Ruler and Compass Constructions

Compass: A tool for marking a circle.

Straightedge: A ruler without any marks on it.

Geometric constructions are delightful by nature, they offer a playfulness to mathematics as well as a new form of creativity. But how do these constructions work, and what are some of the methodologies or proofs that have emerged throughout history? Let’s uncover a few, To begin, we consider the creation of a bisector to a given line.

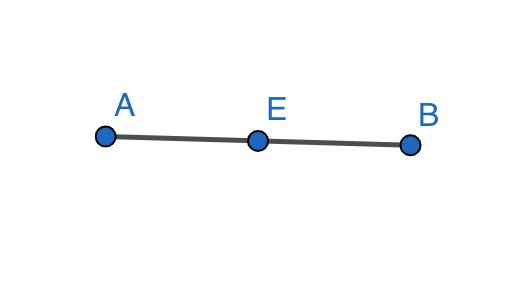

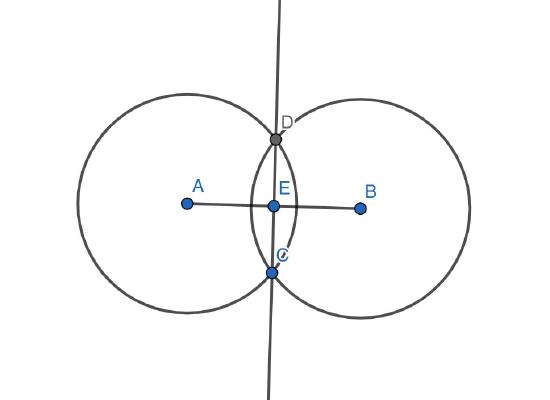

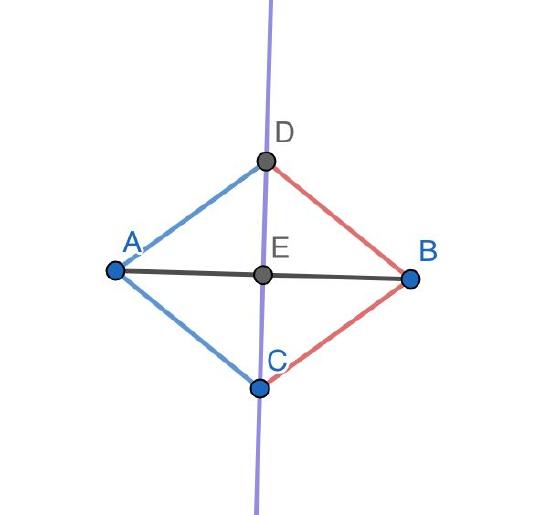

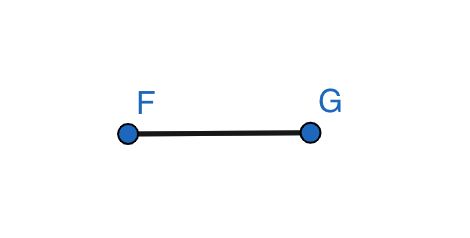

Construction 1: Bisecting a line

Say we are given a line AB.

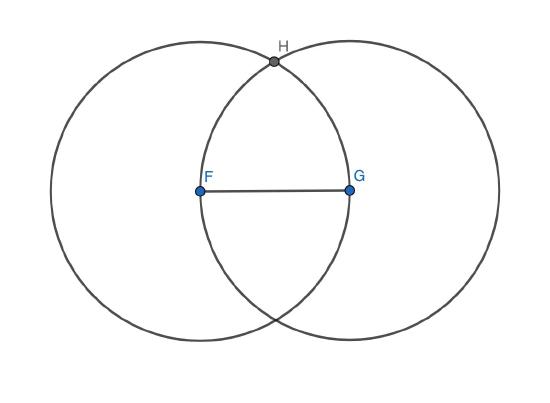

Our first step is to choose point A as the center point for our compass. Extend the compass to create a circle with a radius a little larger than half of length AB and draw the circle. From the other point B, create a circle with the same radius this time with B as the center point. The 2 points of intersection of the two circles will be points on

the straight line CD that bisects AB.

But how can we prove that this line CD is actually a bisector of line AB? One method is to use congruent triangles to show geometrically that CD must be a bisector of AB.

If we join the points the following way, one sees that we’ve created two isosceles triangles DAC and DBC. Because the circles created on points A and B have the same radius, we know that points D and C are an equal distance away from points A and B, thus DB = BC = CA = AD. This demonstrates that the two triangles DAC and DBC are isosceles.

Both triangles also share the same base DC. We know that congruent triangles must have all the same angles and side lengths as each other since both triangles DAC and DBC have two side lengths equal to DB and one shared side length DC, they both have three identical sides to each other and are thus congruent. Congruent triangles have the

same height as each other, thus we know that AE and EB are the same lengths which proves that the line we’ve created is indeed a bisector of line AB.

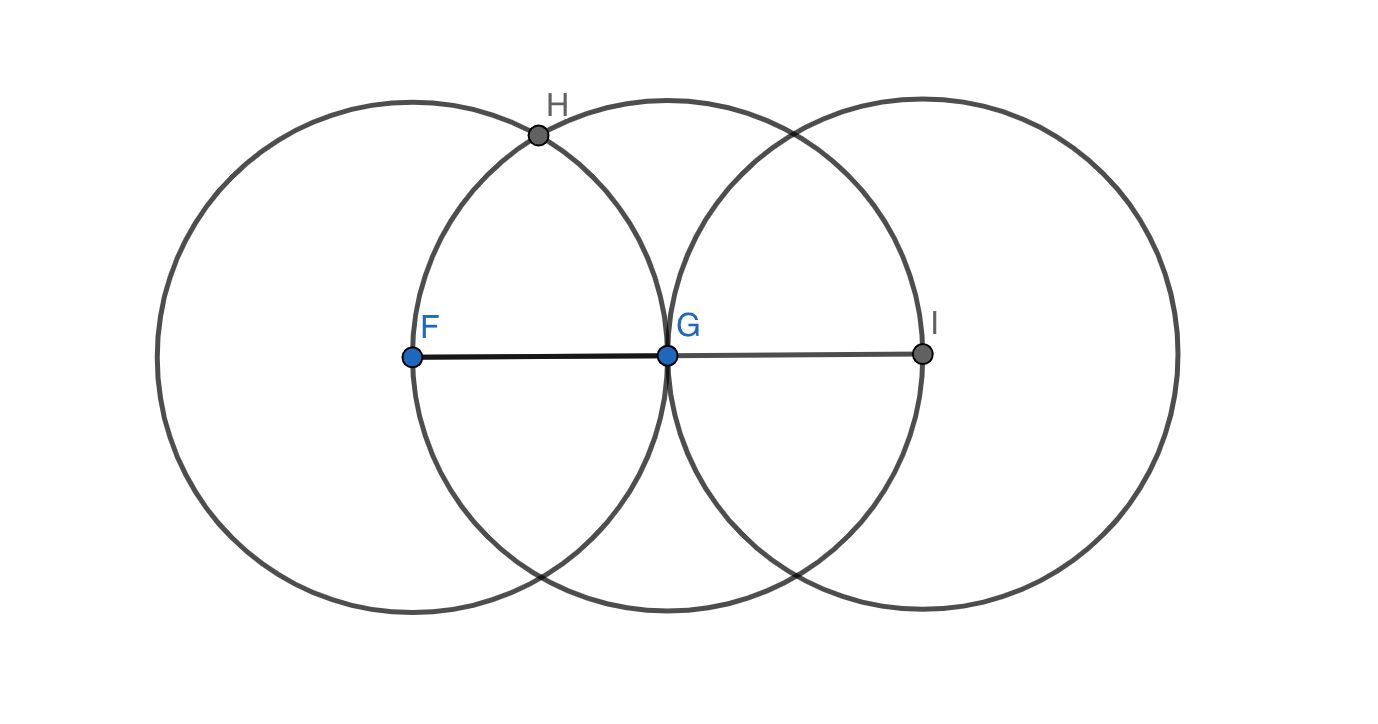

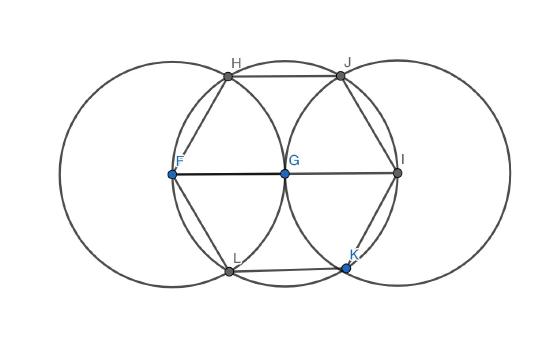

Construction 2: Creating a hexagon, given a line

Given a line FG, create a hexagon with side length FG.

Using a compass, draw a circle with radius FG and center F. Create another circle with radius FG and center point G. Extend line FG to create a new line FI length 2(FG).

Construct yet another circle with radius FG and center point, I. Mark, each point of intersection amongst each of the three circles. Using points F, H, J, I, K, L as vertices, construct a hexagon.

A regular hexagon can be constructed from six congruent equilateral triangles. The use of circles of equal radius enables the construction of multiple equilateral triangles that in turn form a hexagon. For example, we see that triangle FHG is equilateral. Point H is of equal distance from F as is it from G, and the distance of HF and HG is equal also to the distance of FG. Therefore FHG must be equilateral. It then follows that FLG maintains the same criteria and is an equilateral triangle congruent to FHG. Furthermore, it follows that the pattern of construction around point I will also result in congruent equilateral triangles GJI and GKI, for circles of the same radius on I and G will form equilateral triangles much the same way that circles of the same radius formed equilateral triangles on F and G. Given that the angles FGH and IGJ sum to an angle of 120 degrees, it follows that supplementary angle HGJ will be 60 degrees. We know that lines GH and GJ are equal and congruent to lines FG and IF thus HGJ is an equilateral triangle congruent to FHG. Near identical processing will construct triangle LGK and we will see a constructed hexagon with vertices F, H, J, I, K, L. Alternate solutions to the construction of a regular hexagon with side length FG might include bisecting various angles, extending lines, creating identical angles, and many other techniques. The potential solutions for this problem, as with many others, are infinite, so long as the problem is actually solvable that is.

Activity

Construct a regular dodecagon using only a compass and a straight edge.

- Hint

-

Start by drawing a circle with a center, let's say O. Then pick any point on the circle, let's say A. Now construct a circle with center A and the same radius as previous. Continue to construct seven circles using the intersecting points.

The following app/game may help in the construction:

https://www.euclidea.xyz/en/game/packs

For hundreds of years, there were three problems that endlessly tormented mathematicians. Many mathematicians strove endlessly to find solutions to the problems, now

known as the “three classical problems.”

Example \(\PageIndex{14}\):

Using an unmarked straight edge and a compass, try to do the following exercises:

-

Square a circle - given a circle of a certain area, create a square with the same area.

-

Trisect an Angle - divide an angle into three equal parts.

-

Construct a cube with twice the volume of a given cube.

Source:

By Job Bouwman [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia CommonsBy derivative work: Pbroks13 (talk) Square root of 2 triangle.png: en:User:Fredrik Simplified drawing: Rubber Duck (☮ • ✍) (Square root of 2 triangle.png) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By Pbroks13 at English Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

By Cmglee (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

By Vancho at English Wikipedia (Transferred from en.Wikipedia to Commons.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By Cmglee (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

By http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Us...r_Mathematicae (File:Secciones_cónicas.svg) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

By Cflm001 [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Thanks to Hannah Rayner

Tags recommended by the template: article:topic