4.4: Constant Coefficient Homogeneous Systems I

- Page ID

- 17437

This page is a draft and is under active development.

Constant Coefficient Homogenous Systems I

We'll now begin our study of the homogeneous system

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.1}

{\bf y}'=A{\bf y},

\end{equation}

where \(A\) is an \(n\times n\) constant matrix. Since \(A\) is continuous on \((-\infty,\infty)\), Theorem \((4.2.1)\) implies that all solutions of \eqref{eq:4.4.1} are defined on \((-\infty,\infty)\). Therefore, when we speak of solutions of \({\bf y}'=A{\bf y}\), we'll mean solutions on \((-\infty,\infty)\).

In this section we assume that all the eigenvalues of \(A\) are real and that \(A\) has a set of \(n\) linearly independent eigenvectors. In the next two sections we consider the cases where some of the eigenvalues of \(A\) are complex, or where \(A\) does not have \(n\) linearly independent eigenvectors.

In Example \((4.3.2)\) we showed that the vector functions

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ -e^{2t} \\ 2e^{2t} \end{array} \right] \quad \mbox{and} \quad {\bf y}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ -e^{-t} \\ e^{-t} \end{array} \right]

\end{eqnarray*}

form a fundamental set of solutions of the system

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.2}

{\bf y}' = \left[ \begin{array} \\ {-4} & {-3} \\ 6 & 5 \end{array} \right] {\bf y},

\end{equation}

but we did not show how we obtained \({\bf y}_1\) and \({\bf y}_2\) in the first place. To see how these solutions can be obtained we write \eqref{eq:4.4.2} as

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.3}

\begin{array}{ccc}

y_1'&=&-4y_1-3y_2\\y_2'&=&\phantom{-}6y_1+5y_2\end{array}

\end{equation}

and look for solutions of the form

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.4}

y_1=x_1e^{\lambda t} \quad \mbox{and} \quad y_2=x_2e^{\lambda t},

\end{equation}

where \(x_1\), \(x_2\), and \(\lambda\) are constants to be determined. Differentiating \eqref{eq:4.4.4} yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

y_1' = \lambda x_1e^{\lambda t} \quad \mbox{and} \quad y_2'=\lambda x_2e^{\lambda t}.

\end{eqnarray*}

Substituting this and \eqref{eq:4.4.4} into \eqref{eq:4.4.3} and canceling the common factor \(e^{\lambda t}\) yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

\begin{array}{ccc}-4x_1-3x_2&=&\lambda x_1 \\

6 x_1+5x_2&=&\lambda x_2.\end{array}

\end{eqnarray*}

For a given \(\lambda\), this is a homogeneous algebraic system, since it can be rewritten as

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.5}

\begin{array}{rcl} (-4-\lambda) x_1-3 x_2&=&0\\

6 x_1+(5-\lambda) x_2&=&0.\end{array}

\end{equation}

The trivial solution \(x_1=x_2=0\) of this system isn't useful, since it corresponds to the trivial solution \(y_1\equiv y_2\equiv0\) of \eqref{eq:4.4.3}, which can't be part of a fundamental set of solutions of \eqref{eq:4.4.2}. Therefore we consider only those values of \(\lambda\) for which \eqref{eq:4.4.5} has nontrivial solutions. These are the values of \(\lambda\) for which the determinant of \eqref{eq:4.4.5} is zero; that is,

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left|\begin{array}{cc}-4-\lambda&-3\\6&5-\lambda\end{array}\right|&=&

(-4-\lambda)(5-\lambda)+18\\&=&\lambda^2-\lambda-2\\

&=&(\lambda-2)(\lambda+1)=0,

\end{eqnarray*}

which has the solutions \(\lambda_1=2\) and \(\lambda_2=-1\).

Taking \(\lambda=2\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.5} yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

-6 x_1-3 x_2&=&0\\

6 x_1+3 x_2&=&0,

\end{eqnarray*}

which implies that \(x_1=-x_2/2\), where \(x_2\) can be chosen arbitrarily. Choosing \(x_2=2\) yields the solution \(y_1=-e^{2t}\),

\(y_2=2e^{2t}\) of \eqref{eq:4.4.3}. We can write this solution in vector form as

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.6}

{\bf y}_1= \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ {\phantom{-}2} e^{2t} \end{array} \right].

\end{equation}

Taking \(\lambda=-1\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.5} yields the system

\begin{eqnarray*}

-3 x_1-3 x_2&=&0\\

\phantom{-}6 x_1+6 x_2&=&0,

\end{eqnarray*}

so \(x_1=-x_2\). Taking |(x_2=1\) here yields the solution \(y_1=-e^{-t}\), \(y_2=e^{-t}\) of \eqref{eq:4.4.3}. We can write this solution in vector form as

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.7}

{\bf y}_2= \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ {\phantom{-}1}e^{-t} \end{array} \right].

\end{equation}

In \eqref{eq:4.4.6} and \eqref{eq:4.4.7} the constant coefficients in the arguments of the exponential functions are the eigenvalues of the coefficient matrix in \eqref{eq:4.4.2}, and the vector coefficients of the exponential functions are associated eigenvectors. This illustrates the next theorem.

Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Suppose the \(n\times n\) constant matrix \(A\) has \(n\) real eigenvalues \(\lambda_1,\lambda_2,\ldots,\lambda_n\) (which need not be distinct) with associated linearly independent eigenvectors \({\bf x}_1,{\bf x}_2,\ldots,{\bf x}_n\). Then the functions

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_1 = {\bf x}_1 e^{\lambda_1 t}, \, {\bf y}_2 = {\bf x}_2 e^{\lambda_2 t}, \, \dots, \, {\bf y}_n = {\bf x}_n e^{\lambda_n t}

\end{eqnarray*}

form a fundamental set of solutions of \({\bf y}'=A{\bf y};\) that is, the general solution of this system is

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y} = c_1 {\bf x}_1 e^{\lambda_1 t} + c_2 {\bf x}_2 e^{\lambda_2 t} + \cdots + c_n {\bf x}_n e^{\lambda_n t}.

\end{eqnarray*}

- Proof

-

Differentiating \({\bf y}_i={\bf x}_ie^{\lambda_it}\) and recalling that \(A{\bf x}_i=\lambda_i{\bf x}_i\) yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_i' = \lambda_i {\bf x}_i e^{\lambda_i t} = A {\bf x}_i e^{\lambda_i t} = A {\bf y}_i.

\end{eqnarray*}This shows that \({\bf y}_i\) is a solution of \({\bf y}'=A{\bf y}\).

The Wronskian of \(\{{\bf y}_1,{\bf y}_2,\ldots,{\bf y}_n\}\) is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left| \begin{array} \\ x_{11} e^{\lambda_1 t} & x_{12} e^{\lambda_2 t} & \cdots & x_{1n} e^{\lambda_n t} \\ x_{21} e^{\lambda_1 t} & x_{22} e^{\lambda_2 t} & \cdots & x_{2n} e^{\lambda_n t} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ x_{n1} e^{\lambda_1 t} & x_{n2} e^{\lambda_2 t} & \cdots & x_{nn} e^{\lambda x_n} \end{array} \right| = e^{\lambda_1 t} e^{\lambda_2 t} \cdots e^{\lambda_n t} \left| \begin{array} \\ x_{11} & x_{12} & \cdots & x_{1n} \\ x_{21} & x_{22} & \cdots & x_{2n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ x_{n1} & x_{n2} & \cdots & x_{nn} \end{array} \right|.

\end{eqnarray*}Since the columns of the determinant on the right are \({\bf x}_1\), \({\bf x}_2\), \(\dots\), \({\bf x}_n\), which are assumed to be linearly independent, the determinant is nonzero. Therefore Theorem \((4.3.3)\) implies that \(\{{\bf y}_1,{\bf y}_2,\ldots,{\bf y}_n\}\) is a fundamental set of solutions of \({\bf y}'=A{\bf y}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

(a) Find the general solution of

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.8}

{\bf y}'= \left[ \begin{array} \\ 2 & 4 \\ 4 & 2 \end{array} \right] {\bf y}.

\end{equation}

(b) Solve the initial value problem

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.9}

{\bf y}'= \left[ \begin{array} \\ 2 & 4 \\ 4 & 2 \end{array} \right] {\bf y}, \quad {\bf y}(0)= \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\-1 \end{array} \right].

\end{equation}

- Answer

-

(a) The characteristic polynomial of the coefficient matrix \(A\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.8} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left|\begin{array}{cc} 2-\lambda&4\\4&2-\lambda\end{array}\right|

&=& (\lambda-2)^2-16\\

&=& (\lambda-2-4)(\lambda-2+4)\\

&=& (\lambda-6)(\lambda+2).

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(\lambda_1=6\) and \(\lambda_2 =-2\) are eigenvalues of \(A\). To obtain the eigenvectors, we must solve the system

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.10}

\left[\begin{array}{cc} 2-\lambda&4\\4&2-\lambda\end{array}\right]

\left[\begin{array}{c} x_1\\x_2\end{array}\right]=

\left[\begin{array}{c} 0\\0\end{array}\right]

\end{equation}with \(\lambda=6\) and \(\lambda=-2\). Setting \(\lambda=6\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.10} yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ -4 & 4 \\ 4 & -4 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array} \\ x_1 \\ x_2 \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which implies that \(x_1=x_2\). Taking \(x_2=1\) yields the eigenvector

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf x}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}so

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{6t}

\end{eqnarray*}is a solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.8}. Setting \(\lambda=-2\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.10} yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 4 & 4 \\ 4 & 4 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array} \\ x_1 \\ x_2 \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which implies that \(x_1=-x_2\). Taking \(x_2=1\) yields the eigenvector

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf x}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}so

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{-2t}

\end{eqnarray*}is a solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.8}. From Theorem \((4.4.1)\), the general solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.8} is

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.11}

{\bf y}=c_1{\bf y}_1+c_2{\bf y}_2=c_1\left[\begin{array}{r}1\\1\end{array}\right]e^{6t}+c_2\left[\begin{array}{r}-1\\1

\end{array}\right]e^{-2t}.

\end{equation}(b) To satisfy the initial condition in \eqref{eq:4.4.9}, we must choose \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.11} so that

\begin{eqnarray*}

c_1 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] + c_2 \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\ -1 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}This is equivalent to the system

\begin{eqnarray*}

c_1-c_2&=&\phantom{-}5\\

c_1+c_2&=&-1,

\end{eqnarray*}so \(c_1=2, c_2=-3\). Therefore the solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.9} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y} = 2 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{6t} -3 \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{-2t},

\end{eqnarray*}or, in terms of components,

\begin{eqnarray*}

y_1 = 2e^{6t} + 3e^{-2t}, \quad y_2 = 2e^{6t} - 3e^{-2t}.

\end{eqnarray*}

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

(a) Find the general solution of

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.12}

{\bf y}'=\left[\begin{array}{rrr}3&-1&-1\\-2& 3& 2\\4&-1&-2\end{array}\right]{\bf y}.

\end{equation}

(b) Solve the initial value problem

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.13}

{\bf y}'=\left[\begin{array}{rrr}3&-1&-1\\-2&3&

2\\4&-1&-2\end{array}

\right]{\bf y},\quad{\bf y}(0)=\left[\begin{array}{r}2\\

-1\\8\end{array}\right].

\end{equation}

- Answer

-

(a) The characteristic polynomial of the coefficient matrix \(A\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.12} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left| \begin{array} \\ 3-\lambda & -1 & -1 \\ -2 & 3-\lambda & 2 \\ 4 & -1 & -2-\lambda \end{array} \right| = -(\lambda-2)(\lambda-3)(\lambda+1).

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, the eigenvalues of \(A\) are \(\lambda_1=2\), \(\lambda_2=3\), and \(\lambda_3=-1\). To find the eigenvectors, we must solve the system

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.14}

\left[\begin{array}{ccc}3-\lambda&-1&-1\\-2&3-\lambda& 2\\4&-1& -2-\lambda\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{c} x_1\\x_2\\x_3 \end{array} \right]=\left[\begin{array}{r}0\\0\\0\end{array}\right]

\end{equation}with \(\lambda=2\), \(3\), \(-1\). With \(\lambda=2\), the augmented matrix of \eqref{eq:4.4.14} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & -1 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \\ -2 & 1 & 2 & \vdots & 0 \\ 4 & -1 & -4 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 0 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(x_1=x_3\) and \(x_2=0\). Taking \(x_3=1\) yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{2t}

\end{eqnarray*}as a solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.12}. With \(\lambda=3\), the augmented matrix of \eqref{eq:4.4.14} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 0 & -1 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \ -2 & 0 & 2 & \vdots & 0 \\ 4 & -1 & -5 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 0 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(x_1=x_3\) and \(x_2=-x_3\). Taking \(x_3=1\) yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ -1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{3t}

\end{eqnarray*}as a solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.12}. With \(\lambda=-1\), the augmented matrix of \eqref{eq:4.4.14} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 4 & -1 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \\-2 & 4 & 2 & \vdots & 0 \\ 4 & -1 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 0 & -{1 \over 7} & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & {3 \over 7} & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(x_1=x_3/7\) and \(x_2=-3x_3/7\). Taking \(x_3=7\) yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_3 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ -3 \\ 7 \end{array} \right] e^{-t}

\end{eqnarray*}as a solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.12}. By Theorem \((4.4.1)\), the general solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.12} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y} = c_1 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{2t} + c_2 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ -1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{3t} + c_3 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ -3 \\ 7 \end{array} \right] e^{-t},

\end{eqnarray*}which can also be written as

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.15}

{\bf y}=\left[\begin{array}{crc}e^{2t}&e^{3t}&e^{-t}

\\0&-e^{3t}&

-3e^{-t}\\e^{2t}&e^{3t}&\phantom{-}7e^{-t}\end{array}

\right]\left[\begin{array}{c} c_1\\c_2\\c_3\end{array}\right].

\end{equation}(b) To satisfy the initial condition in \eqref{eq:4.4.13} we must choose \(c_1\), \(c_2\), \(c_3\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.15} so that

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & -1 & -3 \\ 1 & 1 & 7 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array} \\ c_1 \\ c_2 \\ c_3 \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 2 \\ -1 \\ 8 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Solving this system yields \(c_1=3\), \(c_2=-2\), \(c_3=1\). Hence, the solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.13} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}&=&\left[\begin{array}{ccc}e^{2t}&e^{3t}&

e^{-t}\\0&-e^{3t}

&-3e^{-t}\\e^{2t}&e^{3t}&7e^{-t}\end{array}

\right]

\left[\begin{array}{r}3\\-2\\1\end{array}\right]\\

&=&3\left[\begin{array}{r}1\\0\\1\end{array}\right]e^{2t}-2

\left[\begin{array}{r}1\\-1\\1\end{array}\right]

e^{3t}+\left[\begin{array}{r}1\\-3\\7\end{array}

\right]e^{-t}.

\end{eqnarray*}

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Find the general solution of

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.16}

{\bf y}'=\left[\begin{array}{rrr}-3&2&2\\

2&-3&2\\2&2&-3

\end{array}\right]{\bf y}.

\end{equation}

- Answer

-

The characteristic polynomial of the coefficient matrix \(A\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.16} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ -3-\lambda & 2 & 2 \\ 2 & -3-\lambda & 2 \\ 2 & 2 & -3-\lambda \end{array} \right] = -(\lambda-1)(\lambda+5)^2.

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(\lambda_1=1\) is an eigenvalue of multiplicity \(1\), while \(\lambda_2=-5\) is an eigenvalue of multiplicity \(2\). Eigenvectors associated with \(\lambda_1=1\) are solutions of the system with augmented matrix

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ -4 & 2 & 2 & \vdots & 0 \\ 2 & -4 & 2 \vdots & 0 \\ 2 & 2 & -4 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 0 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(x_1=x_2=x_3\), and we choose \(x_3=1\) to obtain the solution

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.4.17}

{\bf y}_1=\left[\begin{array}{r}1\\1\\1\end{array}\right]e^t

\end{equation}of \eqref{eq:4.4.16}. Eigenvectors associated with \(\lambda_2=-5\) are solutions of the system with augmented matrix

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 2 & 2 & 2 & \vdots & 0 \\ 2 & 2 & 2 & \vdots & 0 \\ 2 & 2 & 2 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, the components of these eigenvectors need only satisfy the single condition

\begin{eqnarray*}

x_1 + x_2 + x_3 = 0.

\end{eqnarray*}Since there's only one equation here, we can choose \(x_2\) and \(x_3\) arbitrarily. We obtain one eigenvector by choosing \(x_2=0\) and \(x_3=1\), and another by choosing \(x_2=1\) and \(x_3=0\). In both cases \(x_1=-1\). Therefore

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] \quad \mbox{and} \ quad \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right]

\end{eqnarray*}are linearly independent eigenvectors associated with \(\lambda_2= -5\), and the corresponding solutions of \eqref{eq:4.4.16} are

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{-5t} \quad \mbox{and} \quad {\bf y}_3 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] e^{-5t}.

\end{eqnarray*}Because of this and \eqref{eq:4.4.17}, Theorem \((4.4.1)\) implies that the general solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.16} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y} = c_1 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^t + c_2 \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{-5t} + c_3 \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] e^{-5t}.

\end{eqnarray*}

Geometric Properties of Solutions when \(n=2\)

We'll now consider the geometric properties of solutions of a \(2\times 2\) constant coefficient system

\begin{equation} \label{eq:4.4.18}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ {y_1'} \\ {y_2'} \end{array} \right] = \left[\begin{array}{cc}a_{11}&a_{12}\\a_{21}&a_{22}

\end{array}\right] \left[ \begin{array} \\ {y_1} \\ {y_2} \end{array} \right].

\end{equation}

It is convenient to think of a ``\(y_1\)-\(y_2\) plane," where a point is identified by rectangular coordinates \((y_1,y_2)\). If \({\bf y}=\displaystyle{ \left[ \begin{array} \\ {y_1} \\ {y_2} \end{array} \right]}\) is a non-constant solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.18}, then the point \((y_1(t),y_2(t))\) moves along a curve \(C\) in the \(y_1\)-\(y_2\) plane as \(t\) varies from \(-\infty\) to \(\infty\). We call \(C\) the \( \textcolor{blue}{\mbox{trajectory}} \) of \({\bf y}\). (We also say that \(C\) is a trajectory of the system \eqref{eq:4.4.18}.) It's important to note that \(C\) is the trajectory of infinitely many solutions of \eqref{eq:4.4.18}, since if \(\tau\) is any real number, then \({\bf y}(t-\tau)\) is a solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.18} (Exercise \((4.4E.28)\) part (b)), and \((y_1(t-\tau),y_2(t-\tau))\) also moves along \(C\) as \(t\) varies from \(-\infty\) to \(\infty\). Moreover, Exercise \((4.4E.28)\) part (c) implies that distinct trajectories of \eqref{eq:4.4.18} can't intersect, and that two solutions \({\bf y}_1\) and \({\bf y}_2\) of \eqref{eq:4.4.18} have the same trajectory if and only if \({\bf y}_2(t)={\bf y}_1(t-\tau)\) for some \(\tau\).

From Exercise \((4.4E.28)\) part (a), a trajectory of a nontrivial solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.18} can't contain \((0,0)\), which we define to be the trajectory of the trivial solution \({\bf y}\equiv0\). More generally, if \({\bf y}=\displaystyle{ \left[ \begin{array} \\ {k_1} \\ {k_2} \end{array} \right]} \ne{\bf 0}\) is a constant solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.18} (which could occur if zero is an eigenvalue of the matrix of \eqref{eq:4.4.18}), we define the trajectory of \({\bf y}\) to be the single point \((k_1,k_2)\).

To be specific, this is the question: What do the trajectories look like, and how are they traversed? In this section we'll answer this question, assuming that the matrix

\begin{eqnarray*}

A = \left[ \begin{array} \\ a_{11} & a_{12} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} \end{array} \right]

\end{eqnarray*}

of \eqref{eq:4.4.18} has real eigenvalues \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\) with associated linearly independent eigenvectors \({\bf x}_1\) and \({\bf x}_2\). Then the general solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.18} is

\begin{equation} \label{eq:4.4.19}

{\bf y}= c_1{\bf x}_1

e^{\lambda_1 t}+c_2{\bf x}_2e^{\lambda_2 t}.

\end{equation}

We'll consider other situations in the next two sections.

We leave it to you (Exercise \((4.4E.35)\)) to classify the trajectories of \eqref{eq:4.4.18} if zero is an eigenvalue of \(A\). We'll confine our attention here to the case where both eigenvalues are nonzero. In this case the simplest situation is where \(\lambda_1=\lambda_2\ne0\), so \eqref{eq:4.4.19} becomes

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y} = (c_1 {\bf x}_1 + c_2 {\bf x}_2) e^{\lambda_1 t}.

\end{eqnarray*}

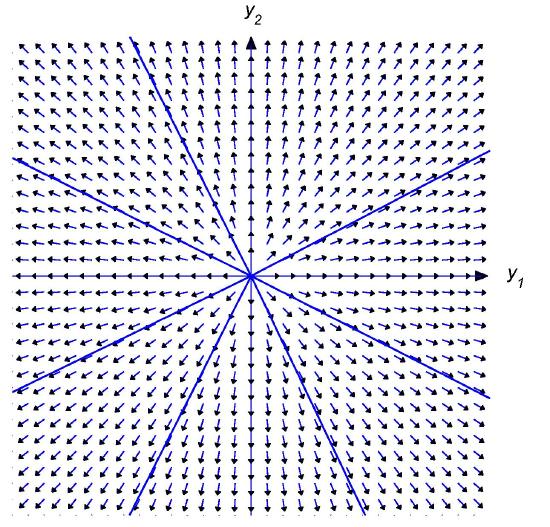

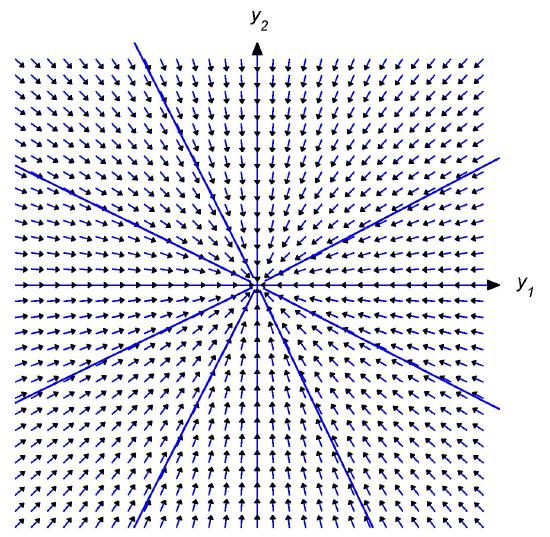

Since \({\bf x}_1\) and \({\bf x}_2\) are linearly independent, an arbitrary vector \({\bf x}\) can be written as \({\bf x}=c_1{\bf x}_1+c_2{\bf x}_2\). Therefore the general solution of \eqref{eq:4.4.18} can be written as \({\bf y}={\bf x}e^{\lambda_1 t}\) where \({\bf x}\) is an arbitrary \(2\)-vector, and the trajectories of nontrivial solutions of \eqref{eq:4.4.18} are half-lines through (but not including) the origin. The direction of motion is away from the origin if \(\lambda_1>0\) (Figure \(4.4.1\)), toward it if \(\lambda_1<0\) (Figure \(4.4.2\)). (In these and the next figures an arrow through a point indicates the direction of motion along the trajectory through the point.)

Figure \(4.4.1\)

Trajectories of a \(2\times 2\) system with a repeated positive

Figure \(4.4.2\)

Trajectories of a \(2\times 2\) system with a repeated negative

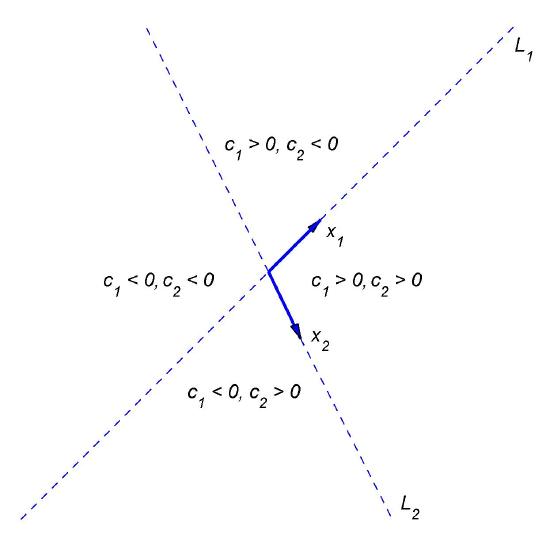

Now suppose \(\lambda_2>\lambda_1\), and let \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) denote lines through the origin parallel to \({\bf x}_1\) and \({\bf x}_2\), respectively. By a half-line of \(L_1\) (or \(L_2\)), we mean either of the rays obtained by removing the origin from \(L_1\) (or \(L_2\)).

Letting \(c_2=0\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.19} yields \({\bf y}=c_1{\bf x}_1e^{\lambda_1 t}\). If \(c_1\ne0\), the trajectory defined by this solution is a half-line of \(L_1\). The direction of motion is away from the origin if \(\lambda_1>0\), toward the origin if \(\lambda_1<0\). Similarly, the trajectory of \({\bf y}=c_2{\bf x}_2e^{\lambda_2 t}\) with \(c_2\ne0\) is a half-line of \(L_2\).

Henceforth, we assume that \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.19} are both nonzero. In this case, the trajectory of \eqref{eq:4.4.19} can't intersect \(L_1\) or \(L_2\), since every point on these lines is on the trajectory of a solution for which either \(c_1=0\) or \(c_2=0\). (Remember: distinct trajectories can't intersect!). Therefore the trajectory of \eqref{eq:4.4.19} must lie entirely in one of the four open sectors bounded by \(L_1\) and \(L_2\), but do not any point on \(L_1\) or \(L_2\). Since the initial point \((y_1(0),y_2(0))\) defined by

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}(0) = c_1 {\bf x}_1 + c_2 {\bf x}_2

\end{eqnarray*}

is on the trajectory, we can determine which sector contains the trajectory from the signs of \(c_1\) and \(c_2\), as shown in Figure \(4.4.3\).

The direction of \({\bf y}(t)\) in \eqref{eq:4.4.19} is the same as that of

\begin{equation} \label{eq:4.4.20}

e^{-\lambda_2 t}{\bf y}(t)=

c_1{\bf x}_1e^{-(\lambda_2-\lambda_1)t}+c_2{\bf x}_2

\end{equation}

and of

\begin{equation} \label{eq:4.4.21}

e^{-\lambda_1 t}{\bf y}(t)=c_1{\bf

x}_1+c_2{\bf x}_2e^{(\lambda_2-\lambda_1)t}.

\end{equation}

Since the right side of \eqref{eq:4.4.20} approaches \(c_2{\bf x}_2\) as \(t\to\infty\), the trajectory is asymptotically parallel to \(L_2\) as \(t\to\infty\). Since the right side of \eqref{eq:4.4.21} approaches \(c_1{\bf x}_1\) as \(t\to-\infty\), the trajectory is asymptotically parallel to \(L_1\) as \(t\to-\infty\).

The shape and direction of traversal of the trajectory of \eqref{eq:4.4.19} depend upon whether \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\) are both positive, both negative, or of opposite signs. We'll now analyze these three cases.

Henceforth \(\|{\bf u}\|\) denote the length of the vector \({\bf u}\).

Figure \(4.4.3\)

Four open sectors bounded by \(L_1\) and \(L_2\)

Figure \(4.4.4\)

Two positive eigenvalues; motion away from origin

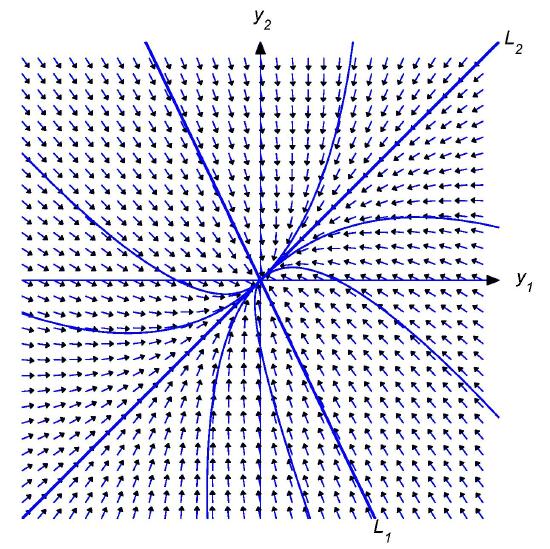

Case 1: \(\lambda_2>\lambda_1>0\)

Figure \(4.4.4\) shows some typical trajectories. In this case, \(\lim_{t\to-\infty}\|{\bf y}(t)\|=0\), so the trajectory is not only asymptotically parallel to \(L_1\) as \(t\to-\infty\), but is actually asymptotically tangent to \(L_1\) at the origin. On the other hand, \(\lim_{t\to\infty}\|{\bf y}(t)\|=\infty\) and

\begin{eqnarray*}

\lim_{t\to\infty} \left\|{\bf y}(t)-c_2{\bf x}_2 e^{\lambda_2 t} \right\| = \lim_{t\to\infty}\|c_1{\bf x_1} e^{\lambda_1 t} \| = \infty,

\end{eqnarray*}

so, although the trajectory is asymptotically parallel to \(L_2\) as \(t\to\infty\), it's not asymptotically tangent to \(L_2\). The direction of motion along each trajectory is away from the origin.

Case 2: \(0>\lambda_2>\lambda_1\)

Figure \(4.4.5\) shows some typical trajectories. In this case, \(\lim_{t\to\infty}\|{\bf y}(t)\|=0\), so the trajectory is asymptotically tangent to \(L_2\) at the origin as \(t\to\infty\). On the other hand, \(\lim_{t\to-\infty}\|{\bf y}(t)\|=\infty\) and

\begin{eqnarray*}

\lim_{t\to-\infty} \left\|{\bf y}(t)-c_1{\bf x}_1 e^{\lambda_1 t} \right\| = \lim_{t\to-\infty} \| c_2{\bf x}_2 e^{\lambda_2 t} \| = \infty,

\end{eqnarray*}

so, although the trajectory is asymptotically parallel to \(L_1\) as \(t\to-\infty\), it's not asymptotically tangent to it. The direction of motion along each trajectory is toward the origin.

Figure \(4.4.5\)

Two negative eigenvalues; motion toward the origin

Figure \(4.4.6\)

Eigenvalues of different signs

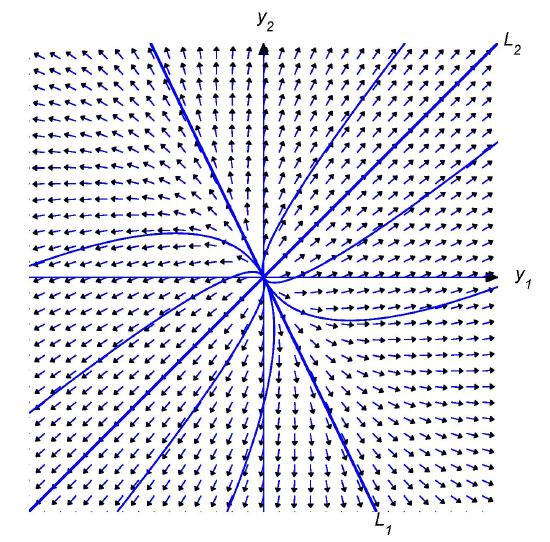

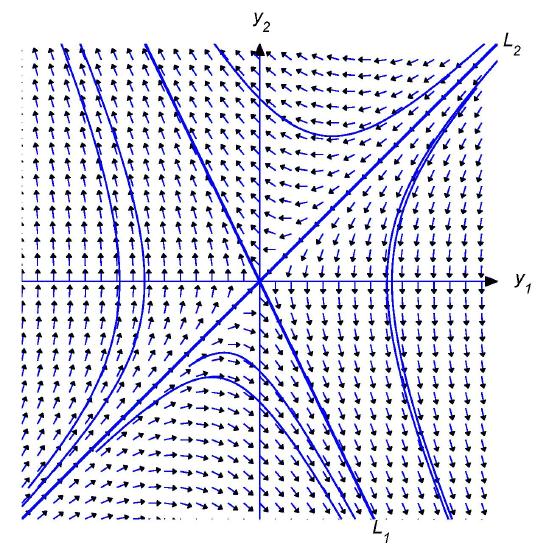

Case 3: \(\lambda_2>0>\lambda_1\)

Figure \(4.4.6\) shows some typical trajectories. In this case,

\begin{eqnarray*}

\lim_{t\to\infty}\|{\bf y}(t)\| = \infty \quad \mbox{and} \quad \lim{|t\to\infty}\left\| {\bf y}(t)-c_2{\bf x}_2 e^{\lambda_2 t} \right\| = \lim_{t\to\infty}\| c_1{\bf x}_1 e^{\lambda_1 t}\| = 0,

\end{eqnarray*}

so the trajectory is asymptotically tangent to \(L_2\) as \(t\to\infty\). Similarly,

\begin{eqnarray*}

\lim_{t\to\infty}\|{\bf y}(t)\| = \infty \quad \mbox{and} \quad \lim_{t\to\infty}\left\|{\bf y}(t)-c_1{\bf x}_1 e^{\lambda_1 t} \right\| = \lim_{t\to\infty}\|c_2{\bf x}_2 e^{\lambda_2 t} \| = 0,

\end{eqnarray*}

so the trajectory is asymptotically tangent to \(L_1\) as \(t\to-\infty\). The direction of motion is toward the origin on \(L_1\) and away from the origin on \(L_2\). The direction of motion along any other trajectory is away from \(L_1\), toward \(L_2\).