4.5: Constant Coefficient Homogeneous Systems II

- Page ID

- 17438

This page is a draft and is under active development.

Constant Coefficient Homogeneous Systems II

We saw in Section 4.4 that if an \(n\times n\) constant matrix \(A\) has \(n\) real eigenvalues \(\lambda_1\), \(\lambda_2\), \(\dots\), \(\lambda_n\) (which need not be distinct) with associated linearly independent eigenvectors \({\bf x}_1\), \({\bf x}_2\), \(\dots\), \({\bf x}_n\), then the general solution of \({\bf y}'=A{\bf y}\) is

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y} = c_1{\bf x}_1 e^{\lambda_1 t} = c_2{\bf x}_2 e^{\lambda_2 t} + \cdots + c_n{\bf x}_n e^{\lambda_n t}.

\end{eqnarray*}

In this section we consider the case where \(A\) has \(n\) real eigenvalues, but does not have \(n\) linearly independent eigenvectors. It is shown in linear algebra that this occurs if and only if \(A\) has at least one eigenvalue of multiplicity \(r>1\) such that the associated eigenspace has dimension less than \(r\). In this case \(A\) is said to be \( \textcolor{blue}{\mbox{defective}} \). Since it's beyond the scope of this book to give a complete analysis of systems with defective coefficient matrices, we will restrict our attention to some commonly occurring special cases.

Example\(\PageIndex{1}\)

Show that the system

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.1}

{\bf y}'= \left[ \begin{array} \\ {11} & {-25} \\ 4 & {-9} \end{array} \right] {\bf y}

\end{equation}

does not have a fundamental set of solutions of the form \(\{{\bf x}_1e^{\lambda_1t},{\bf x}_2e^{\lambda_2t}\}\), where \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\) are eigenvalues of the coefficient matrix \(A\) of \eqref{eq:4.5.1} and \({\bf x}_1\), and \({\bf x}_2\) are associated linearly independent eigenvectors.

- Answer

-

The characteristic polynomial of \(A\) is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ {11} -\lambda & {-25} \\ 4 & {-9} -\lambda \end{array} \right]

&=&(\lambda-11)(\lambda+9)+100\\

&=&\lambda^2-2\lambda+1=(\lambda-1)^2.

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(\lambda=1\) is the only eigenvalue of \(A\). The augmented matrix of the system \((A-I){\bf x}={\bf 0}\) is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 10 & -25 & \vdots & 0 \\ 4 & -10 & \vdots $ 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & -\displaystyle{5 \over 2} & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(x_1=5x_2/2\) where \(x_2\) is arbitrary. Therefore all eigenvectors of \(A\) are scalar multiples of \({\bf x}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\ 2 \end{array} \right]\), so \(A\) does not have a set of two linearly independent eigenvectors.

From Example \((4.5.1)\), we know that all scalar multiples of \({\bf y}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\ 2 \end{array} \right] e^t\) are solutions of \eqref{eq:4.5.1}; however, to find the general solution we must find a second solution \({\bf y}_2\) such that \(\{{\bf y}_1,{\bf y}_2\}\) is linearly independent. Based on your recollection of the procedure for solving a constant coefficient scalar equation

\begin{eqnarray*}

ay'' + by' + cy = 0

\end{eqnarray*}

in the case where the characteristic polynomial has a repeated root, you might expect to obtain a second solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.1} by multiplying the first solution by \(t\). However, this yields \({\bf y}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\ 2 \end{array} \right] te^t\), which doesn't work, since

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_2' = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\ 2 \end{array} \right] (t e^t + e^t), \quad \mbox{while} \quad \left[ \begin{array} \\ 11 & -25 \\ 4 & -9 \end{array} \right] {\bf y}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\ 2 \end{array} \right] t e^t.

\end{eqnarray*}

The next theorem shows what to do in this situation.

Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Suppose the \(n\times n\) matrix \(A\) has an eigenvalue \(\lambda_1\) of multiplicity \(\ge2\) and the associated eigenspace has dimension \(1;\) that is, all \(\lambda_1\)-eigenvectors of \(A\) are scalar multiples of an eigenvector \({\bf x}\). Then there are infinitely many vectors \({\bf u}\) such that

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.2}

(A-\lambda_1I){\bf u}={\bf x}.

\end{equation}

Moreover, if \({\bf u}\) is any such vector then

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.3}

{\bf y}_1={\bf x}e^{\lambda_1t} \quad \mbox{and } \quad {\bf y}_2={\bf u}e^{\lambda_1t}+{\bf x}te^{\lambda_1t}

\end{equation}

are linearly independent solutions of \({\bf y}'=A{\bf y}\).

- Proof

-

Add proof here and it will automatically be hidden if you have a "AutoNum" template active on the page.

A complete proof of this theorem is beyond the scope of this book. The difficulty is in proving that there's a vector \({\bf u}\) satisfying \eqref{eq:4.5.2}, since \(\det(A-\lambda_1I)=0\). We'll take this without proof and verify the other assertions of the theorem.

We already know that \({\bf y}_1\) in \eqref{eq:4.5.3} is a solution of \({\bf y}'=A{\bf y}\). To see that \({\bf y}_2\) is also a solution, we compute

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_2'-A{\bf y}_2&=&\lambda_1{\bf u}e^{\lambda_1t}+{\bf x} e^{\lambda_1t}

+\lambda_1{\bf x} te^{\lambda_1t}-A{\bf u}e^{\lambda_1t}-A{\bf x} te^{\lambda_1t}\\

&=&(\lambda_1{\bf u}+{\bf x} -A{\bf u})e^{\lambda_1t}+(\lambda_1{\bf x} -A{\bf x} )te^{\lambda_1t}.

\end{eqnarray*}

Since \(A{\bf x}=\lambda_1{\bf x}\), this can be written as

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_2' - A{\bf y}_2 = - \left( (A -\lambda_1 l) {\bf u} - {\bf x} \right) e^{\lambda_1 t},

\end{eqnarray*}

and now \eqref{eq:4.5.2} implies that \({\bf y}_2'=A{\bf y}_2\).

To see that \({\bf y}_1\) and \({\bf y}_2\) are linearly independent, suppose \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are constants such that

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.4}

c_1{\bf y}_1+c_2{\bf y}_2=c_1{\bf x}e^{\lambda_1t}+c_2({\bf u}e^{\lambda_1t} +{\bf x}te^{\lambda_1t})={\bf 0}.

\end{equation}

We must show that \(c_1=c_2=0\). Multiplying \eqref{eq:4.5.4} by \(e^{-\lambda_1t}\) shows that

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.5}

c_1{\bf x}+c_2({\bf u} +{\bf x}t)={\bf 0}.

\end{equation}

By differentiating this with respect to \(t\), we see that \(c_2{\bf x}={\bf 0}\), which implies \(c_2=0\), because \({\bf x}\ne{\bf 0}\). Substituting \(c_2=0\) into \eqref{eq:4.5.5} yields \(c_1{\bf x}={\bf 0}\), which implies that \(c_1=0\), again because \({\bf x}\ne{\bf 0}\)

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Use Theorem \((4.5.1)\) to find the general solution of the system

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.6}

{\bf y}' = \left[ \begin{array} \\ {11} & {-25} \\ 4 & {-9} \end{array} \right] {\bf y}

\end{equation}

considered in Example \((4.5.1)\).

- Answer

-

In Example \((4.5.1)\) we saw that \(\lambda_1=1\) is an eigenvalue of multiplicity \(2\) of the coefficient matrix \(A\) in \eqref{eq:4.5.6}, and that all of the eigenvectors of \(A\) are multiples of

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf x} = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\ 2 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Therefore

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\ 2 \end{array} \right] e^t

\end{eqnarray*}is a solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.6}. From Theorem \((4.5.1)\), a second solution is given by \({\bf y}_2={\bf u}e^t+{\bf x}te^t\), where \((A-I){\bf u}={\bf x}\). The augmented matrix of this system is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 10 & -25 & \vdots & 5 \\ 4 & -10 & \vdots & 2 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & -{5 \over 2} & \vdots & {1 \over 2} \\ 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Therefore the components of \({\bf u}\) must satisfy

\begin{eqnarray*}

u_1 - {5 \over 2} u_2 = {1 \over 2},

\end{eqnarray*}where \(u_2\) is arbitrary. We choose \(u_2=0\), so that \(u_1=1/2\) and

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf u} = \left[ \begin{array} \\ {1 \over 2} \\ 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Thus,

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] {e^t \over 2} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\ 2 \end{array} \right] e^t.

\end{eqnarray*}Since \({\bf y}_1\) and \({\bf y}_2\) are linearly independent by Theorem \((4.5.1)\), they form a fundamental set of solutions of \eqref{eq:4.5.6}. Therefore the general solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.6} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y} = c_1 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\ 2 \end{array} \right] e^t + c_2 \left( \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] {e^t \over 2} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ 5 \\ 2 \end{array} \right] t e^t \right)

\end{eqnarray*}

Note that choosing the arbitrary constant \(u_2\) to be nonzero is equivalent to adding a scalar multiple of \({\bf y}_1\) to the second solution \({\bf y}_2\) (Exercise \((4.5E.33)\)).

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Find the general solution of

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.7}

{\bf y}' = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 3 & 4 & {-10} \\ 2 & 1 & {-2} \\ 2 & 2 & {-5} \end{array} \right] {\bf y}.

\end{equation}

- Answer

-

The characteristic polynomial of the coefficient matrix \(A\) in \eqref{eq:4.5.7} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 3-\lambda & 4 & -10 \\ 2 & 1-\lambda & -2 \\ 2 & 2 & -5-\lambda \end{array} \right] = -(\lambda-1)(\lambda+1)^2.

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, the eigenvalues are \(\lambda_1=1\) with multiplicity \(1\) and \(\lambda_2=-1\) with multiplicity \(2\).

Eigenvectors associated with \(\lambda_1=1\) must satisfy \((A-I){\bf x}={\bf 0}\). The augmented matrix of this system is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 2 & 4 & -10 & \vdots & 0 \\ 2 & 0 & -2 & \vdots & 0 \\ 2 & 2 & -6 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right]

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 0 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & -2 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(x_1 =x_3\) and \(x_2 =2 x_3\), where \(x_3\) is arbitrary. Choosing \(x_3=1\) yields the eigenvector

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf x}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 2 \\ 1 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Therefore

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 2 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^t

\end{eqnarray*}is a solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.7}.

Eigenvectors associated with \(\lambda_2 =-1\) satisfy \((A+I){\bf x}={\bf 0}\). The augmented matrix of this system is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 4 & 4 & -10 & \vdots & 0 \\ 2 & 2 & -2 & \vdots & 0 \\ 2 & 2 & -4 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 1 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(x_3=0\) and \(x_1 =-x_2\), where \(x_2\) is arbitrary. Choosing \(x_2=1\) yields the eigenvector

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}so

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] e^{-t}

\end{eqnarray*}is a solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.7}.

Since all the eigenvectors of \(A\) associated with \(\lambda_2=-1\) are multiples of \({\bf x}_2\), we must now use Theorem \((4.5.1)\) to find a third solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.7} in the form

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.8}

{\bf y}_3={\bf u}e^{-t} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ {-1} \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] te^{-t},

\end{equation}where \({\bf u}\) is a solution of \((A+I){\bf u=x}_2\). The augmented matrix of this system is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 4 & 4 & -10 & \vdots & -1 \\ 2 & 2 & -2 & \vdots & 1 \\ 2 & 2 & -4 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 1 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & \vdots & {1 \over 2} \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(u_3=1/2\) and \(u_1 =1-u_2\), where \(u_2\) is arbitrary. Choosing \(u_2=0\) yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf u} = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ {1 \over 2} \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}and substituting this into \eqref{eq:4.5.8} yields the solution

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_3 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 2 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] {e^{-t} \over 2} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] t e^{-t}

\end{eqnarray*}of \eqref{eq:4.5.7}.

Since the Wronskian of \(\{{\bf y}_1,{\bf y}_2,{\bf y}_3\}\) at \(t=0\) is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left| \begin{array} \\ 1 & -1 & 1 \\ 2 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & {1 \over 2} \end{array} \right| = {1 \over 2},

\end{eqnarray*}\(\{{\bf y}_1,{\bf y}_2,{\bf y}_3\}\) is a fundamental set of solutions of \eqref{eq:4.5.7}. Therefore the general solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.7} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y} = c_1 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 2 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^t + c_2 \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] e^{-t} + c_3 \left( \left[ \begin{array} \\ 2 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] {e^{-t} \over 2} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] e^{-t} \right).

\end{eqnarray*}

Theorem \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Suppose the \(n\times n\) matrix \(A\) has an eigenvalue \(\lambda_1\) of multiplicity \(\ge 3\) and the associated eigenspace is one-dimensional; that is, all eigenvectors associated with \(\lambda_1\) are scalar multiples of the eigenvector \({\bf x}.\) Then there are infinitely many vectors \({\bf u}\) such that

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.9}

(A-\lambda_1I){\bf u}={\bf x},

\end{equation}

and, if \({\bf u}\) is any such vector, there are infinitely many vectors \({\bf v}\) such that

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.10}

(A-\lambda_1I){\bf v}={\bf u}.

\end{equation}

If \({\bf u}\) satisfies {\rm\eqref{eq:4.5.9}} and \({\bf v}\) satisfies \eqref{eq:4.5.10}, then

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_1 &=&{\bf x} e^{\lambda_1t},\\

{\bf y}_2&=&{\bf u}e^{\lambda_1t}+{\bf x} te^{\lambda_1t},\mbox{

and }\\

{\bf y}_3&=&{\bf v}e^{\lambda_1t}+{\bf u}te^{\lambda_1t}+{\bf

x} {t^2e^{\lambda_1t}\over2}

\end{eqnarray*}

are linearly independent solutions of \({\bf y}'=A{\bf y}\).

- Proof

-

Add proof here and it will automatically be hidden if you have a "AutoNum" template active on the page.

Again, it's beyond the scope of this book to prove that there are vectors \({\bf u}\) and \({\bf v}\) that satisfy \eqref{eq:4.5.9} and

\eqref{eq:4.5.10}. Theorem \((4.5.1)\) implies that \({\bf y}_1\) and \({\bf y}_2\) are solutions of \({\bf y}'=A{\bf y}\). We leave the rest of the proof to you (Exercise \((4.5E.34)\)).

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Use Theorem \((4.5.2)\) to find the general solution of

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.11}

{\bf y}' = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 3 & {-1} \\ 0 & 2 & 2 \end{array} \right] {\bf y}.

\end{equation}

- Answer

-

The characteristic polynomial of the coefficient matrix \(A\) in \eqref{eq:4.5.11} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left| \begin{array} \\ 1-\lambda & 1 & \phantom{-}1 \\ 1 & 3-\lambda & -1 \\ 0 & 2 & -\lambda \end{array} \right| = -(\lambda-2)^3.

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(\lambda_1=2\) is an eigenvalue of multiplicity \(3\). The associated eigenvectors satisfy \((A-2I){\bf x=0}\). The augmented matrix of this system is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 & 1 & 1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 2 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 0 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(x_1 =x_3\) and \(x_2 = 0\), so the eigenvectors are all scalar multiples of

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf x}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Therefore

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{2t}

\end{eqnarray*}is a solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.11}.

We now find a second solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.11} in the form

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_2 = {\bf u} e^{2t} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] t e^{2t},

\end{eqnarray*}where \({\bf u}\) satisfies \((A-2I){\bf u=x}_1\). The augmented matrix of this system is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 & 1 & 1 & \vdots & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 2 & 0 & \vdots & 1 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 0 & -1 & \vdots & -{1 \over 2} \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & \vdots & {1 \over 2} \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Letting \(u_3=0\) yields \(u_1=-1/2\) and \(u_2=1/2\); hence,

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf u} = {1 \over 2} \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right]

\end{eqnarray*}and

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] {e^{2t} \over 2} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] t e^{2t}

\end{eqnarray*}is a solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.11}.

We now find a third solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.11} in the form

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_3 = {\bf v} e^{2t} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] {t e^{2t} \over 2} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] {t^2 e^{2t} \over 2}

\end{eqnarray*}where \({\bf v}\) satisfies \((A-2I){\bf v}={\bf u}\). The augmented matrix of this system is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 & 1 & 1 & \vdots & -{1 \over 2} \\ 1 & 1 & -1 & \vdots & {1 \over 2} \\ 0 & 2 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array}\\ 1 & 0 & -1 & \vdots & {1 \over 2} \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Letting \(v_3=0\) yields \(v_1=1/2\) and \(v_2=0\); hence,

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf v} = {1 \over 2} \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Therefore

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_3 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] {e^{2t} \over 2} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] {t e^{2t} \over 2} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] {t^2 e^{2t} \over 2}

\end{eqnarray*}is a solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.11}. Since \({\bf y}_1\), \({\bf y}_2\), and \({\bf y}_3\) are linearly independent by Theorem \((4.5.2)\), they form a fundamental set of solutions of \eqref{eq:4.5.11}. Therefore the general solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.11} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y} &=& c_1 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^{2t} + c_2 \left( \left[ \begin{array} \\ {-1} \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] {e^{2t}\over2} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] te^{2t} \right)\\

&& + c_3 \left( \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] {e^{2t}\over2} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ {-1} \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] {te^{2t}\over2} + \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] {t^2e^{2t}\over2} \right).

\end{eqnarray*}

Theorem \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Suppose the \(n\times n\) matrix \(A\) has an eigenvalue \(\lambda_1\) of multiplicity \(\ge 3\) and the associated eigenspace is two-dimensional; that is, all eigenvectors of \(A\) associated with \(\lambda_1\) are linear combinations of two linearly independent eigenvectors \({\bf x}_1\) and \({\bf x}_2\). Then there are constants \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) (not both zero) such that if

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.12}

{\bf x}_3=\alpha{\bf x}_1+\beta{\bf x}_2,

\end{equation}

then there are infinitely many vectors \({\bf u}\) such that

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.13}

(A-\lambda_1I){\bf u}={\bf x}_3.

\end{equation}

If \({\bf u}\) satisfies \eqref{eq:4.5.13}, then

\begin{eqnarray}

{\bf y}_1&=&{\bf x}_1 e^{\lambda_1t},\nonumber\\

{\bf y}_2&=&{\bf x}_2e^{\lambda_1t},\mbox{and }\nonumber\\

{\bf y}_3&=&{\bf u}e^{\lambda_1t}+{\bf x}_3te^{\lambda_1t}\label{eq:4.5.14},

\end{eqnarray}

are linearly independent solutions of \({\bf y}'=A{\bf y}.\)

- Proof

-

We omit the proof of this theorem.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Use Theorem \((4.5.3)\) to find the general solution of

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.15}

{\bf y}' = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ {-1} & 1 & 1 \\ {-1} & 0 & 2 \end{array} \right] {\bf y}.

\end{equation}

- Answer

-

The characteristic polynomial of the coefficient matrix \(A\) in \eqref{eq:4.5.15} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left| \begin{array} \\ -\lambda & 0 & 1 \\ -1 & 1-\lambda & 1 \\ -1 & 0 & 2-\lambda \end{array} \right| = -(\lambda-1)^3.

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(\lambda_1=1\) is an eigenvalue of multiplicity \(3\). The associated eigenvectors satisfy \((A-I){\bf x=0}\). The augmented matrix of this system is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 & 0 & 1 & \vdots & 0 \\ -1 & 0 & 1 & \vdots & 0 \\ -1 & 0 & 1 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 0 & -1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Hence, \(x_1 =x_3\) and \(x_2\) is arbitrary, so the eigenvectors are of the form

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf x}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ x_3 \\ x_2 \\ x_3 \end{array} \right] = x_3 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] + x_2 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Therefore the vectors

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.16}

{\bf x}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] \quad \mbox{and} \quad {\bf x}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right]

\end{equation}form a basis for the eigenspace, and

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_1 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^t \quad \mbox{and} \quad {\bf y}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] e^t

\end{eqnarray*}are linearly independent solutions of \eqref{eq:4.5.15}.

To find a third linearly independent solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.15}, we must find constants \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) (not both zero) such that the system

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.17}

(A-I){\bf u}=\alpha{\bf x}_1+\beta{\bf x}_2

\end{equation}has a solution \({\bf u}\). The augmented matrix of this system is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 & 0 & 1 & \vdots & \alpha \\ -1 & 0 & 1 & \vdots & \beta \\ -1 & 0 & 1 & \vdots & \alpha \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}which is row equivalent to

\begin{equation}\label{eq:4.5.18}

\left[\begin{array}{rrrcr} 1 & 0 &- 1 &\vdots& -\alpha\\ 0 & 0 & 0

&\vdots&\beta-\alpha\\ 0 & 0 & 0 &\vdots&0\end{array}

\right].

\end{equation}Therefore \eqref{eq:4.5.17} has a solution if and only if \(\beta=\alpha\), where \(\alpha\) is arbitrary. If \(\alpha=\beta=1\) then \eqref{eq:4.5.12} and \eqref{eq:4.5.16} yield

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf x}_3 = {\bf x}_1 + {\bf x}_2 = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] + \left[ \begin{array} \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right],

\end{eqnarray*}and the augmented matrix \eqref{eq:4.5.18} becomes

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 & 0 & -1 & \vdots & -1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \vdots & 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}This implies that \(u_1=-1+u_3\), while \(u_2\) and \(u_3\) are arbitrary. Choosing \(u_2=u_3=0\) yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf u} = \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right].

\end{eqnarray*}Therefore \eqref{eq:4.5.14} implies that

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y}_3 = {\bf u} e^t + {\bf x}_3 t e^t = \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] e^t + \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] t e^t

\end{eqnarray*}is a solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.15}. Since \({\bf y}_1\), \({\bf y}_2\), and \({\bf y}_3\) are linearly independent by Theorem \((4.5.3)\), they form a fundamental set of solutions for \eqref{eq:4.5.15}. Therefore the general solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.15} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\bf y} = c_1 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^t + c_2 \left[ \begin{array} \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] e^t + c_3 \left( \left[ \begin{array} \\ -1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] e^t + \left[ \begin{array} \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] e^t \right)

\end{eqnarray*}

Geometric Properties of Solutions when \(n=2\)

We'll now consider the geometric properties of solutions of a \(2\times2\) constant coefficient system

\begin{equation} \label{eq:4.5.19}

\left[ \begin{array} \\ {y_1'} \\ {y_2'} \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array}{cc}a_{11}&a_{12}\\a_{21}&a_{22}

\end{array}\right] \left[ \begin{array} \\ {y_1} \\ {y_2} \end{array} \right]

\end{equation}

under the assumptions of this section; that is, when the matrix

\begin{eqnarray*}

A = \left[ \begin{array} \\ a_{11} & a_{12} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} \end{array} \right]

\end{eqnarray*}

has a repeated eigenvalue \(\lambda_1\) and the associated eigenspace is one-dimensional. In this case we know from Theorem \((4.5.1)\) that the general solution of \eqref{eq:4.5.19} is

\begin{equation} \label{eq:4.5.20}

{\bf y}=c_1{\bf x}e^{\lambda_1t}+c_2({\bf u}e^{\lambda_1t}+{\bf

x}te^{\lambda_1t}),

\end{equation}

where \({\bf x}\) is an eigenvector of \(A\) and \({\bf u}\) is any one of the infinitely many solutions of

\begin{equation} \label{eq:4.5.21}

(A-\lambda_1I){\bf u}={\bf x}.

\end{equation}

We assume that \(\lambda_1\ne0\).

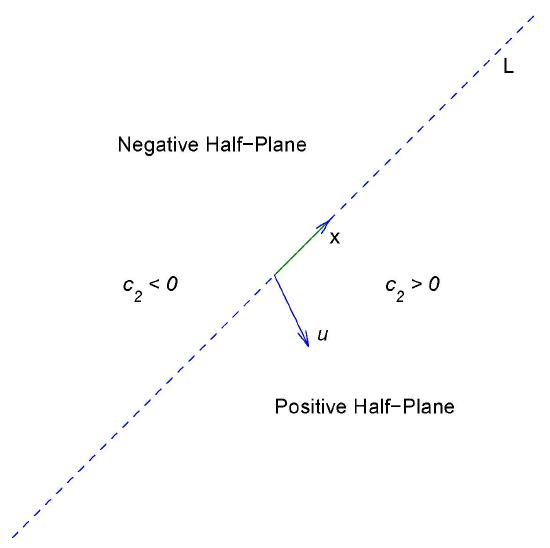

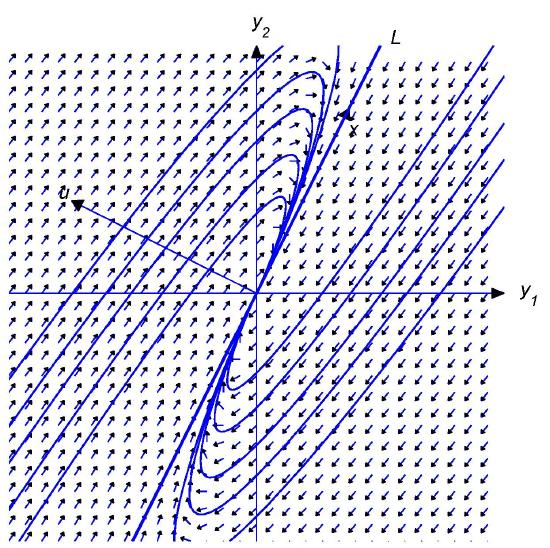

Figure \(4.5.1\)

Positive and negative half-planes

Let \(L\) denote the line through the origin parallel to \({\bf x}\). By a \( \textcolor{blue}{\mbox{half-line}} \) of \(L\) we mean either of the rays obtained by removing the origin from \(L\). Equation \eqref{eq:4.5.20} is a parametric equation of the half-line of \(L\) in the direction of \({\bf x}\) if \(c_1>0\), or of the half-line of |(L\) in the direction of \(-{\bf x}\) if \(c_1<0\). The origin is the trajectory of the trivial solution \({\bf y}\equiv{\bf 0}\).

Henceforth, we assume that \(c_2\ne0\). In this case, the trajectory of \eqref{eq:4.5.20} can't intersect \(L\), since every point of \(L\) is on a trajectory obtained by setting \(c_2=0\). Therefore the trajectory of \eqref{eq:4.5.20} must lie entirely in one of the open half-planes bounded by \(L\), but does not contain any point on \(L\). Since the initial point \((y_1(0),y_2(0))\) defined by \({\bf y}(0)=c_1{\bf x}_1+c_2{\bf u}\) is on the trajectory, we can determine which half-plane contains the trajectory from the sign of \(c_2\), as shown in Figure \(4.5.1\). For convenience we'll call the half-plane where \(c_2>0\) the \( \textcolor{blue}{\mbox{positive half-plane}} \). Similarly, the-half plane where \(c_2<0\) is the \( \textcolor{blue}{\mbox{negative half-plane}} \). You should convince yourself (Exercise \((4.5E.35)\)) that even though there are infinitely many vectors \({\bf u}\) that satisfy \eqref{eq:4.5.21}, they all define the same positive and negative half-planes. In the figures simply regard \({\bf u}\) as an arrow pointing to the positive half-plane, since wen't attempted to give \({\bf u}\) its proper length or direction in comparison with \({\bf x}\). For our purposes here, only the relative orientation of \({\bf x}\) and \({\bf u}\) is important; that is, whether the positive half-plane is to the right of an observer facing the direction of \({\bf x}\) (as in Figures \(4.5.2\) and \(4.5.5\)), or to the left of the observer (as in Figures \(4.5.3\) and \(4.5.4\)).

Multiplying \eqref{eq:4.5.20} by \(e^{-\lambda_1t}\) yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

e^{-\lambda_1 t} {\bf y}(t) = c_1{\bf x} + c_2{\bf u} + c_2 t {\bf x}.

\end{eqnarray*}

Since the last term on the right is dominant when \(|t|\) is large, this provides the following information on the direction of \({\bf y}(t)\):

(a) Along trajectories in the positive half-plane (\(c_2>0\)), the direction of \({\bf y}(t)\) approaches the direction of \({\bf x}\) as \(t\to\infty\) and the direction of \(-{\bf x}\) as \(t\to-\infty\).

(b) Along trajectories in the negative half-plane (\(c_2<0\)), the direction of \({\bf y}(t)\) approaches the direction of \(-{\bf x}\) as \(t\to\infty\) and the direction of \({\bf x}\) as \(t\to-\infty\).

Since

\begin{eqnarray*}

\lim_{t\to\infty} \| {\bf y}(t) \| = \infty \quad \mbox{and} \quad \lim_{t\to-\infty}{\bf y}(t) = {\bf 0} \quad \mbox{if} \quad \lambda_1>0,

\end{eqnarray*}

or

\begin{eqnarray*}

\lim_{t-\to\infty} \| {\bf y}(t) \| = \infty \quad \mbox{and} \quad \lim_{t\to\infty}{\bf y}(t) = {\bf 0} \quad \mbox{if} \quad \lambda_1<0,

\end{eqnarray*}

there are four possible patterns for the trajectories of \eqref{eq:4.5.19}, depending upon the signs of \(c_2\) and \(\lambda_1\).

Figures \(4.5.2\) to \(4.5.5\) illustrate these patterns, and reveal the following principle:

If \(\lambda_1\) and \(c_2\) have the same sign then the direction of the trajectory approaches the direction of \(-{\bf x}\) as \(\|{\bf y} \|\to0\) and the direction of \({\bf x}\) as \(\|{\bf y}\|\to\infty\) If \(\lambda_1\) and \(c_2\) have opposite signs then the direction of the trajectory approaches the direction of \({\bf x}\) as \(\|{\bf y} \|\to0\) and the direction of \(-{\bf x}\) as \(\|{\bf y}\|\to\infty\).

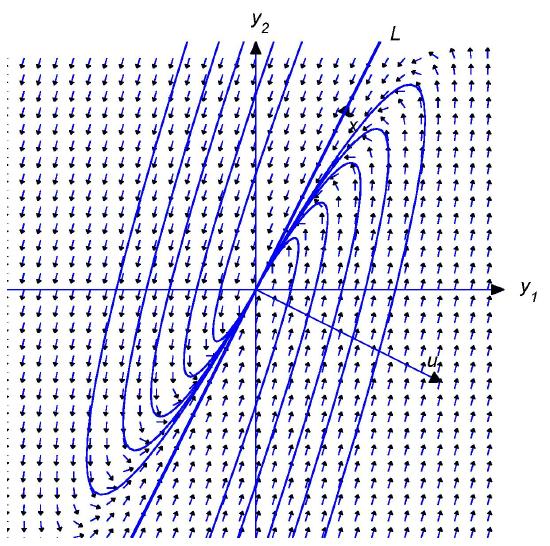

Figure \(4.5.2\)

Positive eigenvalue; motion away from the origin

Positive eigenvalue; motion away from the origin

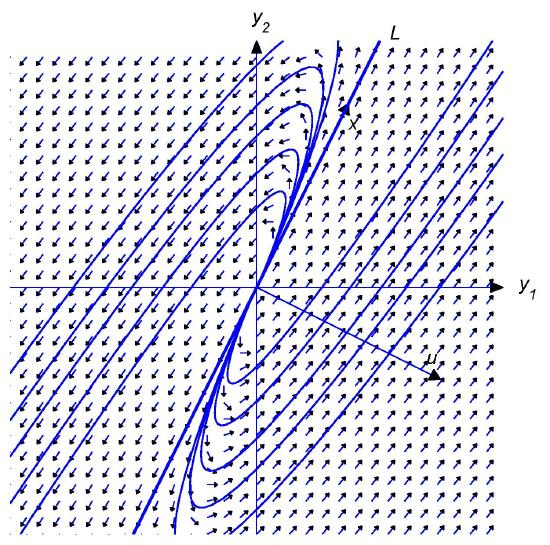

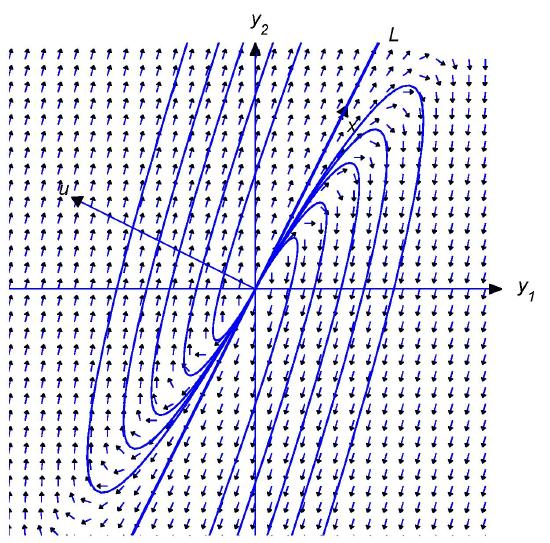

Negative eigenvalue; motion toward the origin

Figure \(4.5.5\)

Negative eigenvalue; motion toward the origin