5.4: Other Algebraic Functions

- Page ID

- 4011

This section serves as a watershed for functions which are combinations of polynomial, and more generally, rational functions, with the operations of radicals. It is business of Calculus to discuss these functions in all the detail they demand so our aim in this section is to help shore up the requisite skills needed so that the reader can answer Calculus's call when the time comes. We briefly recall the definition and some of the basic properties of radicals from Intermediate Algebra.\footnote{Although we discussed imaginary numbers in Section 3.4, we restrict our attention to real numbers in this section. See the epilogue for more details.}

Definition 5.4:

Let \(x\) be a real number and \(n\) a natural number. \footnote{Recall this means \(n=1,2,3,\ldots\).} If \(n\) is odd, the \(n^{\textrm{th}}\) root \(\textbf{principal\) \(\boldmath n^{\textbf{th}}\) root} of \(x\), denoted \(\sqrt[n]{x}\) is the unique real number satisfying \(\left(\sqrt[n]{x}\right)^n = x\). If \(n\) is even, \(\sqrt[n]{x}\) is defined similarly\footnote{Recall both \(x=-2\) and \(x=2\) satisfy \(x^4=16\), but \(\sqrt[4]{16} =2\), not \(-2\).} provided \(x \geq 0\) and \(\sqrt[n]{x} \geq 0\). The \index{root ! index} \(\textbf{index}\) is the number \(n\) and the \(\textbf{radicand}\) is the number \(x\). For \(n=2\), we write \(\sqrt{x}\) instead of \(\sqrt[2]{x}\).

It is worth remarking that, in light of Section 5.2, we could define \(f(x) = \sqrt[n]{x}\) functionally as the inverse of \(g(x) = x^n\) with the stipulation that when \(n\) is even, the domain of \(g\) is restricted to \([0, \infty)\). From what we know about \(g(x) = x^n\) from Section 3.1 along with Theorem 5.3, we can produce the graphs of \(f(x) = \sqrt[n]{x}\) by reflecting the graphs of \(g(x) = x^n\) across the line \(y=x\). Below are the graphs of \(y=\sqrt{x}\), \(y=\sqrt[4]{x}\) and \(y=\sqrt[6]{x}\). The point \((0,0)\) is indicated as a reference. The axes are hidden so we can see the vertical steepening near \(x=0\) and the horizontal flattening as \(x \rightarrow \infty\).

\[ \begin{array}{ccc} \begin{mfpic}[10]{0}{9}{0}{3} \arrow \parafcn{0,3,0.1}{(t^2,t)} \point[2pt]{(0,0)} \tcaption{\scriptsize \y=\sqrt{x}\)} \end{mfpic} & \begin{mfpic}[10]{0}{9}{0}{3} \arrow \parafcn{0,1.732,0.1}{(t^4,t)} \point[2pt]{(0,0)} \tcaption{\scriptsize \(y=\sqrt[4]{x}\)} \end{mfpic}& \begin{mfpic}[10]{0}{9}{0}{3} \arrow \parafcn{0,1.442,0.1}{(t^6,t)}\point[2pt]{(0,0)} \tcaption{\scriptsize \(y=\sqrt[6]{x}\)} \end{mfpic}\end{array}\]

The odd-indexed radical functions also follow a predictable trend - steepening near \(x = 0\) and flattening as \(x \rightarrow \pm \infty\). In the exercises, you'll have a chance to graph some basic radical functions using the techniques presented in Section 1.7.

\[ \begin{array}{ccc} \begin{mfpic}[10]{-9}{9}{0}{3} \arrow \reverse \arrow \parafcn{-1.587,1.587,0.1}{(t^3,t)} \point[2pt]{(0,0)} \tcaption{\scriptsize $y=\sqrt[3]{x}$} \end{mfpic} & \begin{mfpic}[10]{-9}{9}{0}{3} \arrow \reverse \arrow \parafcn{-1.319,1.319,0.1}{(t^5,t)} \point[2pt]{(0,0)} \tcaption{\scriptsize $y=\sqrt[5]{x}$} \end{mfpic} & \begin{mfpic}[10]{-9}{9}{0}{3}\arrow \reverse \arrow \parafcn{-1.219,1.219,0.1}{(t^7,t)} \point[2pt]{(0,0)} \tcaption{\scriptsize $y=\sqrt[7]{x}$} \end{mfpic} \end{array}\]

We have used all of the following properties at some point in the textbook for the case \(n=2\) (the square root), but we list them here in generality for completeness.

Theorem 5.6: Properties of Radicals

Let \(x\) and \(y\) be real numbers and \(m\) and \(n\) be natural numbers. If \(\sqrt[n]{x}\), \(\sqrt[n]{y}\) are real numbers, then

- \(\textbf{Product Rule:}\) \(\sqrt[n]{xy} = \sqrt[n]{x} \, \sqrt[n]{y}\)

- \(\textbf{Powers of Radicals:}\) \(\sqrt[n]{x^m} = \left(\sqrt[n]{x}\right)^m\)

- \(\textbf{Quotient Rule:}\) \(\sqrt[n]{\dfrac{x}{y}} = \dfrac{\sqrt[n]{x}}{\sqrt[n]{y}}\), provided \(y \neq 0\).

- If \(n\) is odd, \(\sqrt[n]{x^n} = x\); if \(n\) is even, \(\sqrt[n]{x^n} = |x|\).

The proof of Theorem 5.6 is based on the definition of the principal roots and properties of exponents. To establish the product rule, consider the following. If \(n\) is odd, then by definition \(\sqrt[n]{xy}\) is the unique real number such that \((\sqrt[n]{xy})^{n} = xy \). Given that \(\left( \sqrt[n]{x} \, \sqrt[n]{y}\right)^n = \left(\sqrt[n]{x}\right)^n \left(\sqrt[n]{y}\right)^n = xy \), it must be the case that \(\\sqrt[n]{xy} = \sqrt[n]{x} \, \sqrt[n]{y}). If \(n\) is even, then \(\sqrt[n]{xy}\) is the unique non-negative real number such that \((\sqrt[n]{xy})^{n} = xy \). Also note that since \(n\) is even, \(\sqrt[n]{x}\) and \(\sqrt[n]{y}\) are also non-negative and hence so is \(\sqrt[n]{x}\sqrt[n]{y} \). Proceeding as above, we find that \(\\sqrt[n]{xy} = \sqrt[n]{x} \, \sqrt[n]{y}). The quotient rule is proved similarly and is left as an exercise. The power rule results from repeated application of the product rule, so long as \(\sqrt[n]{x}\) is a real number to start with.\footnote{Otherwise we'd run into the same paradox we did in Section 3.4.} The last property is an application of the power rule when \(n\) is odd, and the occurrence of the absolute value when \(n\) is even is due to the requirement that \(\sqrt[n]{x} \geq 0\) in Definition 5.4. For instance, \(\sqrt[4]{(-2)^4} = \sqrt[4]{16}= 2 = |-2|\), not \(-2\). It's this last property which makes compositions of roots and powers delicate. This is especially true when we use exponential notation for radicals. Recall the following definition.

Definition 5.5:

Let \(x\) be a real number, \(m\) an integer\footnote{Recall this means \(m = 0, \pm 1, \pm 2, \ldots\)} and \(n\) a natural number.

- \( x^{\frac{1}{n}} = \sqrt[n]{x}\) and is defined whenever \(\sqrt[n]{x}\) is defined.

- \( x^{\frac{m}{n}} = \left(\sqrt[n]{x}\right)^m = \sqrt[n]{x^m} \), whenever \( \left(\sqrt[n]{x}\right)^{m} \) is defined.

The rational exponents defined in Definition 5.5 behave very similarly to the usual integer exponents from Elementary Algebra with one critical exception. Consider the expression \( \left(x^{2/3}\right)^{3/2} \). Applying the usual laws of exponents, we'd be tempted to simplify this as \(\left(x^{2/3}\right)^{3/2} = x^{\frac{2}{3} \cdot \frac{3}{2}} = x^{1} = x \). However, if we substitute \(x=-1\) and apply Definition 5.5, we find \((-1)^{2/3} = \left(\sqrt[3]{-1}\right)^2 = (-1)^2 = 1\) so that \( \left((-1)^{2/3}\right)^{3/2} = 1^{3/2} = \left(\sqrt{1}\right)^3 = 1^3 = 1\). We see in this case that \(\left(x^{2/3}\right)^{3/2} \neq x\). If we take the time to rewrite \( \left(x^{2/3}\right)^{3/2} \) with radicals, we see

\[ \left(x^{2/3}\right)^{3/2} = \left(\left(\sqrt[3]{x}\right)^2\right)^{3/2} = \left(\sqrt{\left(\sqrt[3]{x}\right)^2}\right)^3 =\left(\left|\sqrt[3]{x}\right|\right)^3 = \left| \left(\sqrt[3]{x}\right)^3 \right| = |x|\]

In the play-by-play analysis, we see that when we canceled the \(2\)'s in multiplying \(\frac{2}{3} \cdot \frac{3}{2}\), we were, in fact, attempting to cancel a square with a square root. The fact that \(\sqrt{x^2} = |x|\) and not simply \(x\) is the root\footnote{Did you like that pun?} of the trouble. It may amuse the reader to know that \(\left(x^{3/2}\right)^{2/3} = x\), and this verification is left as an exercise. The moral of the story is that when simplifying fractional exponents, it's usually best to rewrite them as radicals.\footnote{In most other cases, though, rational exponents are preferred.} The last major property we will state, and leave to Calculus to prove, is that radical functions are continuous on their domains, so the Intermediate Value Theorem, Theorem 3.1, applies. This means that if we take combinations of radical functions with polynomial and rational functions to form what the authors consider \index{function ! algebraic} the \( \textbf{algebraic functions} \),\footnote{As mentioned in Section 4.2, \(f(x) = \sqrt{x^2}=|x|\) so that absolute value is also considered an algebraic functions.} we can make sign diagrams using the procedure set forth in Section 4.2.

Steps for Constructing a Sign Diagram for an Algebraic Function

Suppose \(f\) is an algebraic function.

- Place any values excluded from the domain of \(f\) on the number line with an `‽' above them.

- Find the zeros of \(f\) and place them on the number line with the number \(0\) above them.

- Choose a test value in each of the intervals determined in steps 1 and 2.

- Determine the sign of \(f(x)\) for each test value in step 3, and write that sign above the corresponding interval.

Our next example reviews quite a bit of Intermediate Algebra and demonstrates some of the new features of these graphs.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

- \(f(x) = 3x \sqrt[3]{2-x}\)

- \(g(x) = \sqrt{2-\sqrt[4]{x+3}}\)

- \(h(x) = \sqrt[3]{\dfrac{8x}{x+1}}\)

- \(k(x) = \dfrac{2x}{\sqrt{x^2 - 1}}\)

\( \bf Solution.\)

1. As far as domain is concerned, \(f(x)\) has no denominators and no even roots, which means its domain is $(-\infty, \infty)$. To create the sign diagram, we find the zeros of \(f\).

\[ \begin{array}{rclr} f(x) & = & 0 & \\ 3x \sqrt[3]{2-x} & = & 0 \\ 3x = 0 & \mbox{or} & \sqrt[3]{2-x} = 0 & \\ x = 0 & \mbox{or} & \left(\sqrt[3]{2-x}\right)^3 = 0^3 & \\ x = 0 & \mbox{or} & 2-x = 0 & \\ x = 0 & \mbox{or} & x=2 & \\ \end{array}\]

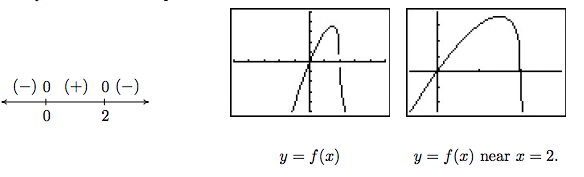

The zeros \(0\) and \(2\) divide the real number line into three test intervals. The sign diagram and accompanying graph are below. Note that the intervals on which \(f\) is \( (+) \) correspond to where the graph of \(f\) is above the \(x\)-axis, and where the graph of \(f\) is below the \(x\)-axis we have that \(f\) is \( (-) \). The calculator suggests something mysterious happens near \(x=2\). Zooming in shows the graph becomes nearly vertical there. You'll have to wait until Calculus to fully understand this phenomenon.

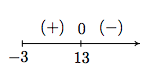

2. In \(g(x) = \sqrt{2-\sqrt[4]{x+3}}\), we have two radicals both of which are even indexed. To satisfy \( \sqrt[4]{x+3} \), we require \( x+3 \geq 0 \) or \( x \geq -3 \). To satisfy \( \sqrt{2-\sqrt[4]{x+3}} \), we need \(2-\sqrt[4]{x+3} \geq 0\). While it may be tempting to write this as \(2 \geq \sqrt[4]{x+3}\) and take both sides to the fourth power, there are times when this technique will produce erroneous results.\footnote{For instance, \(-2 \geq \sqrt[4]{x+3}\), which has no solution or \(-2 \leq \sqrt[4]{x+3}\) whose solution is \([-3,\infty)\).} Instead, we solve \(2-\sqrt[4]{x+3} \geq 0\) using a sign diagram. If we let \(r(x) = 2-\sqrt[4]{x+3}\), we know \( x \geq -3 \), so we concern ourselves with only this portion of the number line. To find the zeros of \(r\) we set \(r(x) =0\) and solve \(2-\sqrt[4]{x+3}=0\). We get \( \sqrt[4]{x+3} = 2\) so that \( \left(\sqrt[4]{x+3}\right)^4 = 2^4\) from which we obtain \(x+3 = 16\) or \(x=13\). Since we raised both sides of an equation to an even power, we need to check to see if \(x=13\) is an extraneous solution.\footnote{Recall, this means we have produced a candidate which doesn't satisfy the original equation. Do you remember how raising both sides of an equation to an even power could cause this?} We find \(x=13\) does check since \(2-\sqrt[4]{x+3} = 2 - \sqrt[4]{13+3} = 2 - \sqrt[4]{16} = 2 - 2 = 0\). Below is our sign diagram for \(r\).

We find \(2-\sqrt[4]{x+3} \geq 0\) on \([-3,13]\) so this is the domain of \(g\). To find a sign diagram for \(g\), we look for the zeros of \(g\). Setting \(g(x) = 0\) is equivalent to \(\sqrt{2-\sqrt[4]{x+3}}=0\). After squaring both sides, we get \(2-\sqrt[4]{x+3} = 0\), whose solution we have found to be \(x=13\). Since we squared both sides, we double check and find \(g(13)\) is, in fact, \(0\). Our sign diagram and graph of \(g\) are below. Since the domain of \(g\) is \([-3,13]\), what we have below is not just a \( \textit{portion} \)of the graph of \(g\), but the \( \textit{complete} \) graph. It is always above or on the \(x\)-axis, which verifies our sign diagram.

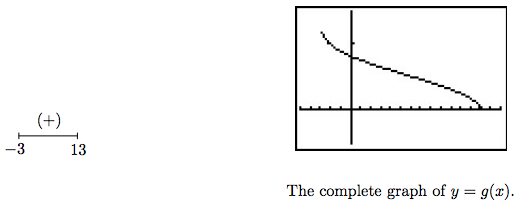

3. The radical in \(h(x)\) is odd, so our only concern is the denominator. Setting \( x+1=0 \) gives \(x=-1\), so our domain is \((-\infty, -1) \cup (-1, \infty) \). To find the zeros of \( h \), we set \( h(x) = 0 \).

To solve \( \sqrt[3]{\frac{8x}{x+1}} = 0 \), we cube both sides to get \(\frac{8x}{x+1} = 0 \). We get \( 8x=0 \), or \(x=0\). Below is the resulting sign diagram and corresponding graph. From the graph, it appears as though \(x=-1\) is a vertical asymptote. Carrying out an analysis as \( x \rightarrow -1 \) as in Section 4.2 confirms this. (We leave the details to the reader.) Near \(x=0\), we have a situation similar to \(x=2\) in the graph of \(f\) in number 1 above. Finally, it appears as if the graph of \( h \) has a horizontal asymptote $y=2$. Using techniques from Section 4.2, we find as \(x \rightarrow \pm \infty\), \( \frac{8x}{x+1} \rightarrow 8 \). From this, it is hardly surprising that as \(x \rightarrow \pm \infty\), \( h(x) = \sqrt[3]{\frac{8x}{x+1}} \approx \sqrt[3]{8} =2 \).

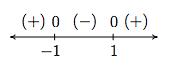

4. To find the domain of \(k\), we have both an even root and a denominator to concern ourselves with. To satisfy the square root, \(x^2 - 1 \geq 0\). Setting \(r(x) = x^2-1\), we find the zeros of \(r\) to be \(x = \pm 1\), and we find the sign diagram of \(r\) to be

We find \(x^2 - 1 \geq 0\) for \((-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)\). To keep the denominator of \(k(x)\) away from zero, we set \( \sqrt{x^2-1} = 0 \). We leave it to the reader to verify the solutions are \(x = \pm 1\), both of which must be excluded from the domain. Hence, the domain of \(k\) is \( (-\infty, -1) \cup (1,\infty) \). To build the sign diagram for \(k\), we need the zeros of \(k\). Setting \( k(x) = 0 \) results in \( \frac{2x}{\sqrt{x^2 - 1}}= 0 \). We get \( 2x =0\) or \(x=0\). However, \(x=0\) isn't in the domain of \(k\), which means \(k\) has no zeros. We construct our sign diagram on the domain of \(k\) below alongside the graph of \(k\). It appears that the graph of \(k\) has two vertical asymptotes, one at \(x=-1\) and one at \(x=1 \). The gap in the graph between the asymptotes is because of the gap in the domain of \(k\). Concerning end behavior, there appear to be two horizontal asymptotes, \(y = 2 \) and \(y=-2\). To see why this is the case, we think of \(x\rightarrow \pm \infty\). The radicand of the denominator \(x^2 - 1 \approx x^2\), and as such, \(k(x) = \frac{2x}{\sqrt{x^2 - 1}} \approx \frac{2x}{\sqrt{x^2}} = \frac{2x}{|x|}\). As \(x \rightarrow \infty\), we have \(|x| = x\) so \(k(x) \approx \frac{2x}{x} = 2\). On the other hand, as \(x \rightarrow -\infty\), \(|x| = -x\), and as such \(k(x) \approx \frac{2x}{-x} = -2\). Finally, it appears as though the graph of \(k\) passes the Horizontal Line Test which means \(k\) is one to one and \( k^{-1} \) exists. Computing \( k^{-1} \) is left as an exercise.

As the previous example illustrates, the graphs of general algebraic functions can have features we've seen before, like vertical and horizontal asymptotes, but they can occur in new and exciting ways. For example, $k(x) = \frac{2x}{\sqrt{x^{2} - 1}}$ had two distinct horizontal asymptotes. You'll recall that rational functions could have at most one horizontal asymptote. Also some new characteristics like `unusual steepness'\footnote{The proper Calculus term for this is `vertical tangent', but for now we'll be okay calling it `unusual steepness'.} and cusps\footnote{See page \pageref{cusppicture} for the first reference to this feature.} can appear in the graphs of arbitrary algebraic functions. Our next example first demonstrates how we can use sign diagrams to solve nonlinear inequalities. (Don't panic. The technique is very similar to the ones used in Chapters \ref{LinearQuadratic}, \ref{Polynomials} and \ref{Rationals}.) We then check our answers graphically with a calculator and see some of the new graphical features of the functions in this extended family.

\begin{ex} Solve the following inequalities. Check your answers graphically with a calculator.

\begin{multicols}{2}

\begin{enumerate}

$x^{2/3} < x^{4/3} - 6$

$3 (2-x)^{1/3} \leq x (2-x)^{-2/3}$

\end{enumerate}

\end{multicols}

\( \bf Solution.\)

\begin{enumerate}

To solve $x^{2/3} < x^{4/3} - 6$, we get \(0\) on one side and attempt to solve $x^{4/3} - x^{2/3} - 6 > 0$. We set $r(x) = x^{4/3} - x^{2/3} - 6$ and note that since the denominators in the exponents are $3$, they correspond to cube roots, which means the domain of \(r\) is $(-\infty, \infty)$. To find the zeros for the sign diagram, we set $r(x) = 0$ and attempt to solve $x^{4/3} - x^{2/3} - 6 = 0$. At this point, it may be unclear how to proceed. We could always try as a last resort converting back to radical notation, but in this case we can take a cue from Example \ref{usubex}. Since there are three terms, and the exponent on one of the variable terms, $x^{4/3}$, is exactly twice that of the other, $x^{2/3}$, we have ourselves a `quadratic in disguise' and we can rewrite $ x^{4/3} - x^{2/3} - 6 = 0$ as $\left(x^{2/3}\right)^2 - x^{2/3} - 6=0$. If we let $u = x^{2/3}$, then in terms of $u$, we get $u^2 - u - 6 = 0$. Solving for $u$, we obtain $u = -2$ or $u = 3$. Replacing $x^{2/3}$ back in for $u$, we get $x^{2/3} = -2$ or $x^{2/3} = 3$. To avoid the trouble we encountered in the discussion following Definition 5.5, we now convert back to radical notation. By interpreting $x^{2/3}$ as $\sqrt[3]{x^2}$ we have $\sqrt[3]{x^2} = -2$ or $\sqrt[3]{x^2}= 3$. Cubing both sides of these equations results in $x^2 = -8$, which admits no real solution, or $x^2 = 27$, which gives $x = \pm 3 \sqrt{3}$. We construct a sign diagram and find $x^{4/3} - x^{2/3} - 6 > 0$ on $\left(-\infty, -3 \sqrt{3}\right)\cup \left(3 \sqrt{3}, \infty\right)$. To check our answer graphically, we set $f(x) = x^{2/3}$ and $g(x) = x^{4/3}-6$. The solution to $x^{2/3} < x^{4/3} - 6$ corresponds to the inequality $f(x) < g(x)$, which means we are looking for the \(x\) values for which the graph of \(f\) is below the graph of \(g\). Using the `Intersect' command we confirm\footnote{Or at least confirm to several decimal places} that the graphs cross at $x= \pm 3\sqrt{3}$. We see that the graph of \(f\) is below the graph of \(g\) (the thicker curve) on $\left(-\infty, -3 \sqrt{3}\right)\cup \left(3 \sqrt{3}, \infty\right)$.

\begin{center}

\begin{tabular}{m{2.5in}c}

\begin{mfpic}[10]{-5}{5}{-1}{2}

\arrow \reverse \arrow \polyline{(-5,0),(5,0)}

\xmarks{-2,2}

\tlabel[cc](-3.5,1){\( (+) \)}

\tlabel[cc](-2,-1){$-3 \sqrt{3} \hspace{7pt}$}

\tlabel[cc](-2,1){\(0\)}

\tlabel[cc](0,1){\( (-) \)}

\tlabel[cc](2,-1){$3 \sqrt{3}$}

\tlabel[cc](2,1){\(0\)}

\tlabel[cc](3.5,1){\( (+) \)}

\end{mfpic}

&

\includegraphics[width=2in]{./FurtherGraphics/Algebraic06.jpg} \\

& $y = f(x)$ and \boldmath $y = g(x)$ \\

\end{tabular}

\end{center}

As a point of interest, if we take a closer look at the graphs of \(f\) and \(g\) near \(x=0\) with the axes off, we see that despite the fact they both involve cube roots, they exhibit different behavior near \(x=0\). The graph of \(f\) has a sharp turn, or cusp, while \(g\) does not.\footnote{Again, we introduced this feature on page \pageref{cusppicture} as a feature which makes the graph of a function `not smooth'.}

\begin{center}

\begin{tabular}{cc}

\includegraphics[width=2in]{./FurtherGraphics/Algebraic07.jpg} & \includegraphics[width=2in]{./FurtherGraphics/Algebraic08.jpg} \\

$y=f(x)$ near \(x=0\) & $y=g(x)$ near \(x=0\) \\

\end{tabular}

\end{center}

To solve $3 (2-x)^{1/3} \leq x (2-x)^{-2/3}$, we gather all the nonzero terms on one side and obtain $3 (2-x)^{1/3} - x (2-x)^{-2/3} \leq 0$. We set $r(x) = 3 (2-x)^{1/3} - x (2-x)^{-2/3}$. As in number 1, the denominators of the rational exponents are odd, which means there are no domain concerns there. However, the negative exponent on the second term indicates a denominator. Rewriting $r(x)$ with positive exponents, we obtain \[r(x) = 3 (2-x)^{1/3} - \frac{x}{(2-x)^{2/3}}\] Setting the denominator equal to zero we get $(2-x)^{2/3} = 0$, or $\sqrt[3]{(2-x)^2} = 0$. After cubing both sides, and subsequently taking square roots, we get $2-x=0$, or \(x=2\). Hence, the domain of \(r\) is $(-\infty, 2) \cup (2, \infty)$. To find the zeros of \(r\), we set $r(x) = 0$. There are two school of thought on how to proceed and we demonstrate both.

\begin{itemize}

\textit{Factoring Approach.} From $r(x) = 3 (2-x)^{1/3} - x (2-x)^{-2/3}$, we note that the quantity $(2-x)$ is common to both terms. When we factor out common factors, we factor out the quantity with the \textit{smaller} exponent. In this case, since $-\frac{2}{3} < \frac{1}{3}$, we factor $(2-x)^{-2/3}$ from both quantities. While it may seem odd to do so, we need to factor $(2-x)^{-2/3}$ \textit{from} $(2-x)^{1/3}$, which results in subtracting the exponent $-\frac{2}{3}$ from $\frac{1}{3}$. We proceed using the usual properties of exponents.\footnote{And we exercise special care when reducing the $\frac{3}{3}$ power to $1$.}

\[ \begin{array}{rclr}

r(x) & = & 3 (2-x)^{1/3} - x (2-x)^{-2/3} & \\ [3pt]

& = & (2-x)^{-2/3} \left[ 3 (2-x)^{\frac{1}{3} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)} - x\right] & \\ [6pt]

& = & (2-x)^{-2/3}\left[3(2-x)^{3/3} - x\right] & \\ [3pt]

& = & (2-x)^{-2/3}\left[3(2-x)^{1} - x\right] & \mbox{since $\sqrt[3]{u^3} = \left(\sqrt[3]{u}\right)^{3} = u$} \\ [3pt]

& = & (2-x)^{-2/3}\left(6-4x\right) & \\ [3pt]

& = & (2-x)^{-2/3}\left(6-4x\right) & \\

\end{array}\]

To solve $r(x) = 0$, we set $(2-x)^{-2/3}\left(6-4x\right) = 0$, or $\frac{6-4x}{(2-x)^{2/3}} = 0$. We have $6-4x = 0$ or $x = \frac{3}{2}$.

\pagebreak

\textit{Common Denominator Approach.} We rewrite

\[ \begin{array}{rclr}

r(x) & = & 3 (2-x)^{1/3} - x (2-x)^{-2/3} & \\ [3pt]

& = & 3 (2-x)^{1/3} - \dfrac{x}{(2-x)^{2/3}} & \\ [10pt]

& = & \dfrac{3 (2-x)^{1/3}(2-x)^{2/3}}{(2-x)^{2/3}} - \dfrac{x}{(2-x)^{2/3}} & \mbox{common denominator} \\ [10pt]

& = & \dfrac{3 (2-x)^{\frac{1}{3} + \frac{2}{3}}}{(2-x)^{2/3}} - \dfrac{x}{(2-x)^{2/3}} & \\ [10pt]

& = & \dfrac{3 (2-x)^{3/3}}{(2-x)^{2/3}} - \dfrac{x}{(2-x)^{2/3}} & \\ [10pt]

& = & \dfrac{3 (2-x)^1}{(2-x)^{2/3}} - \dfrac{x}{(2-x)^{2/3}} & \mbox{since $\sqrt[3]{u^3} = \left(\sqrt[3]{u}\right)^{3} = u$} \\ [10pt]

& = & \dfrac{3 (2-x) - x}{(2-x)^{2/3}} & \\ [10pt]

& = & \dfrac{6-4x}{(2-x)^{2/3}} & \\

\end{array}\]

As before, when we set $r(x) = 0$ we obtain $x = \frac{3}{2}$.

\end{itemize}

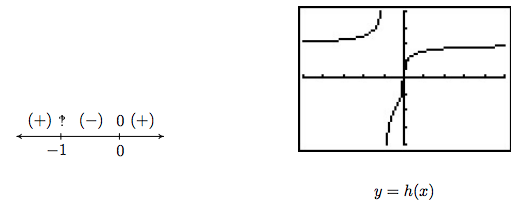

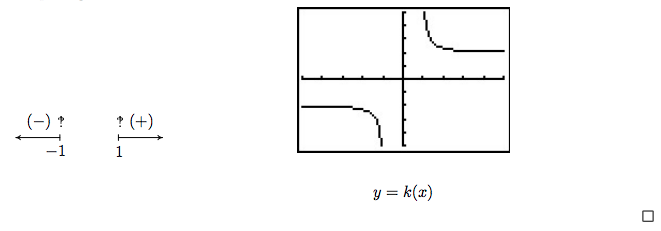

We now create our sign diagram and find $3 (2-x)^{1/3} - x (2-x)^{-2/3} \leq 0$ on $\left[\frac{3}{2},2\right) \cup (2, \infty)$. To check this graphically, we set $f(x)=3 (2-x)^{1/3}$ and $g(x) = x (2-x)^{-2/3}$ (the thicker curve). We confirm that the graphs intersect at $x=\frac{3}{2}$ and the graph of \(f\) is below the graph of \(g\) for $x \geq \frac{3}{2}$, with the exception of \(x=2\) where it appears the graph of \(g\) has a vertical asymptote.

\begin{center}

\begin{tabular}{m{2.5in}c}

\begin{mfpic}[10]{-5}{5}{-1}{2}

\arrow \reverse \arrow \polyline{(-5,0),(5,0)}

\xmarks{-2,2}

\tlabel[cc](-3.5,1){\( (+) \)}

\tlabel[cc](-2,-1.25){$\frac{3}{2}$}

\tlabel[cc](-2,1){\(0\)}

\tlabel[cc](0,1){\( (-) \)}

\tlabel[cc](2,-1){\(2\)}

\tlabel[cc](2,1){‽}

\tlabel[cc](3.5,1){\( (-) \)}

\end{mfpic}

&

\includegraphics[width=2in]{./FurtherGraphics/Algebraic09.jpg} \\

& $y = f(x)$ and \boldmath $y = g(x)$ \\

\end{tabular}

\end{center}

\end{enumerate}

\vspace{-.30in} \qed

\end{ex}

One application of algebraic functions was given in Example \ref{distancefunctionex} in Section \ref{CartesianPlane}. Our last example is a more sophisticated application of distance.

\begin{ex} \label{SasquatchCable} Carl wishes to get high speed internet service installed in his remote Sasquatch observation post located $30$ miles from Route $117$. The nearest junction box is located $50$ miles downroad from the post, as indicated in the diagram below. Suppose it costs $\$ 15$ per mile to run cable along the road and $\$ 20$ per mile to run cable off of the road.

\begin{center}

\begin{mfpic}[15]{-1}{15}{-1}{9}

\xmarks{0, 4}

\arrow \reverse \arrow \polyline{(0,8.75),(0,0.25)}

\arrow \reverse \arrow \polyline{(0.25,0),(3.75,0)}

\arrow \reverse \arrow \polyline{(4.25,0),(9.75,0)}

\arrow \reverse \arrow \polyline{(0,-1),(10,-1)}

\dashed \polyline{(4,0),(0,9)}

\point[3pt]{(0,9), (10,0)}

\tlabel[cc](1.25,9){\scriptsize Outpost}

\tlabel[cc](12,0){\scriptsize Junction Box}

\tlabel[cc](7,0.5){\(x\)}

\tlabel[cc](2,0.5){ \(y\)}

\tlabel[cc](3,4.5){$z$}

\tlabel[cc](5,-.5){\scriptsize Route $117$}

\tlabel[cc](5,-2){\scriptsize $50$ miles}

\tlabel[cc](-0.5,0){\rotatebox{90}{\hspace{1.5in} \scriptsize $30$ miles}}

\end{mfpic}

\end{center}

\begin{enumerate}

Express the total cost $C$ of connecting the Junction Box to the Outpost as a function of \(x\), the number of miles the cable is run along Route $117$ before heading off road directly towards the Outpost. Determine a reasonable applied domain for the problem.

Use your calculator to graph $y=C(x)$ on its domain. What is the minimum cost? How far along Route $117$ should the cable be run before turning off of the road?

\end{enumerate}

\( \bf Solution.\)

\begin{enumerate}

- The cost is broken into two parts: the cost to run cable along Route $117$ at $\$15$ per mile, and the cost to run it off road at $\$20$ per mile. Since \(x\) represents the miles of cable run along Route $117$, the cost for that portion is $15x$. From the diagram, we see that the number of miles the cable is run off road is $z$, so the cost of that portion is $20z$. Hence, the total cost is $C = 15x + 20z$. Our next goal is to determine $z$ as a function of \(x\). The diagram suggests we can use the Pythagorean Theorem to get $y^2+30^2 = z^2$. But we also see $x+y = 50$ so that $y=50-x$. Hence, $z^2 = (50-x)^2+900$. Solving for $z$, we obtain $z = \pm \sqrt{(50-x)^2+900}$. Since $z$ represents a distance, we choose $z = \sqrt{(50-x)^2+900}$ so that our cost as a function of \(x\) only is given by \[C(x) = 15x + 20\sqrt{(50-x)^2+900}\] From the context of the problem, we have $0 \leq x \leq 50$.

- Graphing $y=C(x)$ on a calculator and using the `Minimum' feature, we find the relative minimum (which is also the absolute minimum in this case) to two decimal places to be $(15.98, 1146.86)$. Here the \(x\)-coordinate tells us that in order to minimize cost, we should run $15.98$ miles of cable along Route 117 and then turn off of the road and head towards the outpost. The \(y\)-coordinate tells us that the minimum cost, in dollars, to do so is $\$1146.86$. The ability to stream live SasquatchCasts? Priceless. \qed

\end{enumerate}