2.2: The Commutative Property of Addition and Multiplication

- Page ID

- 13968

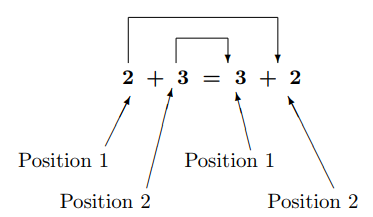

Figure 2.2.1

\(2\) commuted (traveled) from position 1 to position 2

and

\(3\) commuted (traveled) from position 2 to position 1.

Note

A commuter is a traveler. Do not say “communitive" property.

Figure 2.2.1 illustrates the commutative property of addition.

In general

\[\boxed{\Large a+b=b+a}\]

where \(a\) and \(b\) are any real numbers (like \(-6.4\), \(\displaystyle \frac{2}{7}\), \(\pi\)). Any real number can hide in the \(a\)-box or the \(b\)-box.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Is subtraction commutative?

Is \(3-1=1-3\) a true statement?

Solution

No, because \(3-1-2\) and \(1-3=-2\). If we find one counterexample, one example that shows that subtraction is not commutative, the general property (using \(a\) and \(b\)) does not exist.

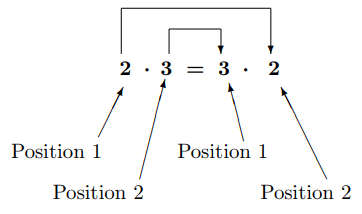

Figure 2.2.2

\(2\) commuted (traveled) from position 1 to position 2

and

\(3\) commuted (traveled) from position 2 to position 1.

Figure 2.2.2 illustrates the commutative property of multiplication.

In general

\[\boxed{\Large ab=ba}\]

where \(a\) and \(b\) are any real numbers (like \(-6.4\), \(\displaystyle \frac{2}{7}\), \(\pi\)). Any real number can hide in the \(a\)-box or the \(b\)-box.

Note that \(ab\) means \(a\) times \(b\).

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Is division commutative?

Is \(4\div 2=2\div 4\) a true statement?

Solution

No, because \(4\div 2=2\) and \(2\div 4=\displaystyle \frac{1}{2}=0.5\). If we find one counterexample, one example that shows that division is not commutative, the general property (using \(a\) and \(b\)) does not exist