6.9: Calculus of the Hyperbolic Functions

- Page ID

- 2527

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Apply the formulas for derivatives and integrals of the hyperbolic functions.

- Apply the formulas for the derivatives of the inverse hyperbolic functions and their associated integrals.

- Describe the common applied conditions of a catenary curve.

We were introduced to hyperbolic functions previously, along with some of their basic properties. In this section, we look at differentiation and integration formulas for the hyperbolic functions and their inverses.

Derivatives and Integrals of the Hyperbolic Functions

Recall that the hyperbolic sine and hyperbolic cosine are defined as

\[\sinh x=\dfrac{e^x−e^{−x}}{2} \nonumber \]

and

\[\cosh x=\dfrac{e^x+e^{−x}}{2}. \nonumber \]

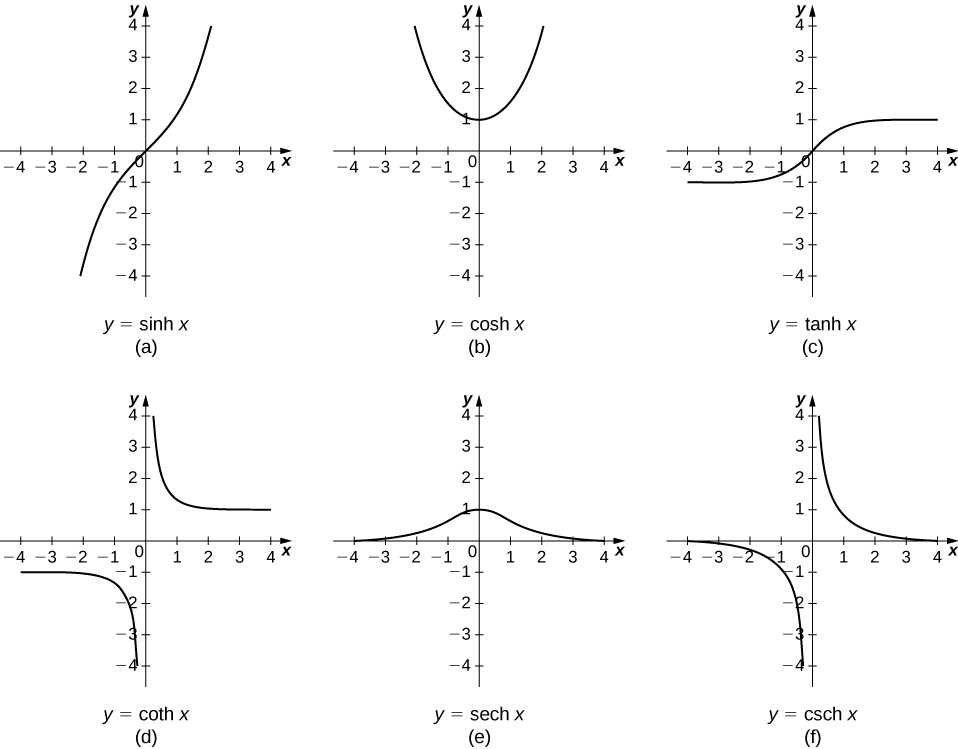

The other hyperbolic functions are then defined in terms of \(\sinh x\) and \(\cosh x\). The graphs of the hyperbolic functions are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

It is easy to develop differentiation formulas for the hyperbolic functions. For example, looking at \(\sinh x\) we have

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{d}{dx} \left(\sinh x \right) &=\dfrac{d}{dx} \left(\dfrac{e^x−e^{−x}}{2}\right) \\[4pt] &=\dfrac{1}{2}\left[\dfrac{d}{dx}(e^x)−\dfrac{d}{dx}(e^{−x})\right] \\[4pt] &=\dfrac{1}{2}[e^x+e^{−x}] \\[4pt] &=\cosh x. \end{align*} \nonumber \]

Similarly,

\[\dfrac{d}{dx} \cosh x=\sinh x. \nonumber \]

We summarize the differentiation formulas for the hyperbolic functions in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\).

| \(f(x)\) | \(\dfrac{d}{dx}f(x)\) |

|---|---|

| \(\sinh x\) | \(\cosh x\) |

| \(\cosh x\) | \(\sinh x\) |

| \(\tanh x\) | \(\text{sech}^2 \,x\) |

| \(\text{coth } x\) | \(−\text{csch}^2\, x\) |

| \(\text{sech } x\) | \(−\text{sech}\, x \tanh x\) |

| \(\text{csch } x\) | \(−\text{csch}\, x \coth x\) |

Let’s take a moment to compare the derivatives of the hyperbolic functions with the derivatives of the standard trigonometric functions. There are a lot of similarities, but differences as well. For example, the derivatives of the sine functions match:

\[\dfrac{d}{dx} \sin x=\cos x \nonumber \]

and

\[\dfrac{d}{dx} \sinh x=\cosh x. \nonumber \]

The derivatives of the cosine functions, however, differ in sign:

\[\dfrac{d}{dx} \cos x=−\sin x, \nonumber \]

but

\[\dfrac{d}{dx} \cosh x=\sinh x. \nonumber \]

As we continue our examination of the hyperbolic functions, we must be mindful of their similarities and differences to the standard trigonometric functions. These differentiation formulas for the hyperbolic functions lead directly to the following integral formulas.

\[ \begin{align} \int \sinh u \,du &=\cosh u+C \\[4pt] \int \text{csch}^2 u \, du &=−\coth u+C \\[4pt] \int \cosh u \,du &=\sinh u+C \\[4pt] \int \text{sech} \,u \tanh u \,du &=−\text{sech } \,u+C−\text{csch} \,u+C \\[4pt] \int \text{sech }^2u \,du &=\tanh u+C \\[4pt] \int \text{csch} \,u \coth u \,du &=−\text{csch} \,u+C \end{align} \nonumber \]

Evaluate the following derivatives:

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sinh(x^2))\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\cosh x)^2\)

Solution:

Using the formulas in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) and the chain rule, we get

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sinh(x^2))=\cosh(x^2)⋅2x\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\cosh x)^2=2\cosh x\sinh x\)

Evaluate the following derivatives:

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\tanh(x^2+3x))\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\dfrac{1}{(\sinh x)^2}\right)\)

- Hint

-

Use the formulas in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) and apply the chain rule as necessary.

- Answer a

-

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\tanh(x^2+3x))=(\text{sech}^2(x^2+3x))(2x+3)\)

- Answer b

-

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\dfrac{1}{(\sinh x)^2}\right)=\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sinh x)^{−2}=−2(\sinh x)^{−3}\cosh x\)

Evaluate the following integrals:

- \( \displaystyle \int x\cosh(x^2)dx\)

- \( \displaystyle \int \tanh x\,dx\)

Solution

We can use \(u\)-substitution in both cases.

a. Let \(u=x^2\). Then, \(du=2x\,dx\) and

\[\begin{align*} \int x\cosh (x^2)dx &=\int \dfrac{1}{2}\cosh u\,du \\[4pt] &=\dfrac{1}{2}\sinh u+C \\[4pt] &=\dfrac{1}{2}\sinh (x^2)+C. \end{align*}\]

b. Let \(u=\cosh x\). Then, \(du=\sinh x\,dx\) and

\[\begin{align*} \int \tanh x \,dx &=\int \dfrac{\sinh x}{\cosh x}\,dx \\[4pt] &=\int \dfrac{1}{u}du \\[4pt] &=\ln|u|+C \\[4pt] &= \ln|\cosh x|+C.\end{align*}\]

Note that \(\cosh x>0\) for all \(x\), so we can eliminate the absolute value signs and obtain

\[\int \tanh x \,dx=\ln(\cosh x)+C. \nonumber \]

Evaluate the following integrals:

- \(\displaystyle \int \sinh^3x \cosh x \,dx\)

- \(\displaystyle \int \text{sech }^2(3x)\, dx\)

- Hint

-

Use the formulas above and apply \(u\)-substitution as necessary.

- Answer a

-

\(\displaystyle \int \sinh^3x \cosh x \,dx=\dfrac{\sinh^4x}{4}+C\)

- Answer b

-

\(\displaystyle \int \text{sech }^2(3x) \, dx=\dfrac{\tanh(3x)}{3}+C\)

Calculus of Inverse Hyperbolic Functions

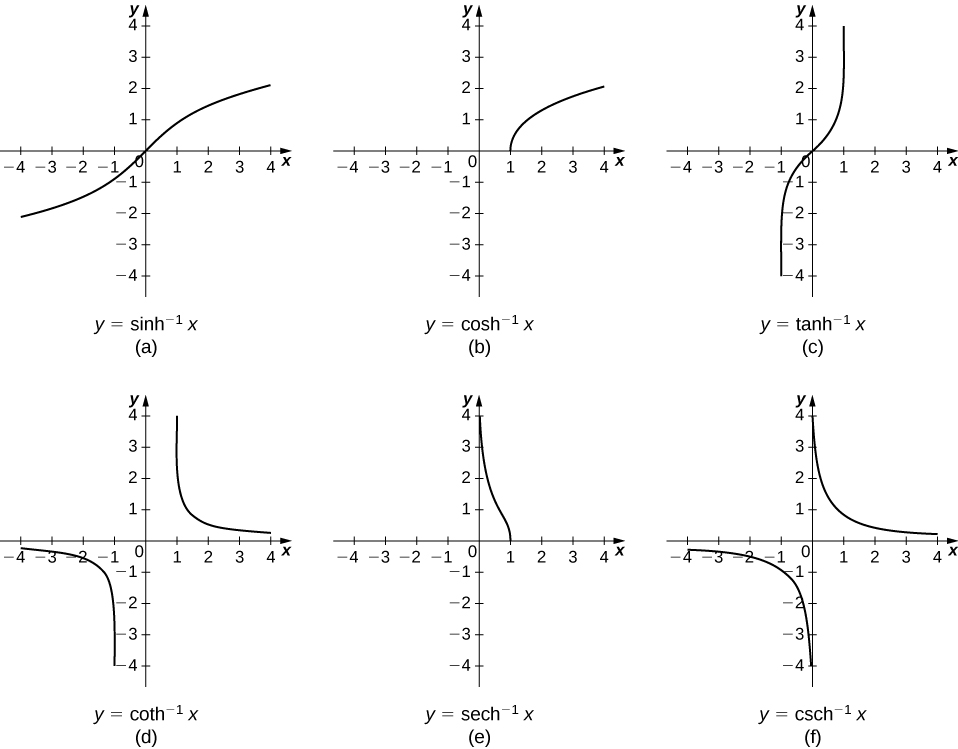

Looking at the graphs of the hyperbolic functions, we see that with appropriate range restrictions, they all have inverses. Most of the necessary range restrictions can be discerned by close examination of the graphs. The domains and ranges of the inverse hyperbolic functions are summarized in Table \(\PageIndex{2}\).

| Function | Domain | Range |

|---|---|---|

| \(\sinh^{−1}x\) | (−∞,∞) | (−∞,∞) |

| \(\cosh^{−1}x\) | (1,∞) | [0,∞) |

| \(\tanh^{−1}x\) | (−1,1) | (−∞,∞) |

| \(\coth^{−1}x\) | (−∞,1)∪(1,∞) | (−∞,0)∪(0,∞) |

| \(\text{sech}^{−1}x\) | (0,1) | [0,∞) |

| \(\text{csch}^{−1}x\) | (−∞,0)∪(0,∞) | (−∞,0)∪(0,∞) |

The graphs of the inverse hyperbolic functions are shown in the following figure.

To find the derivatives of the inverse functions, we use implicit differentiation. We have

\[\begin{align} y &=\sinh^{−1}x \\[4pt] \sinh y &=x \\[4pt] \dfrac{d}{dx} \sinh y &=\dfrac{d}{dx}x \\[4pt] \cosh y\dfrac{dy}{dx} &=1. \end{align} \nonumber \]

Recall that \(\cosh^2y−\sinh^2y=1,\) so \(\cosh y=\sqrt{1+\sinh^2y}\).Then,

\[\dfrac{dy}{dx}=\dfrac{1}{\cosh y}=\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1+\sinh^2y}}=\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1+x^2}}. \nonumber \]

We can derive differentiation formulas for the other inverse hyperbolic functions in a similar fashion. These differentiation formulas are summarized in Table \(\PageIndex{3}\).

| \(f(x)\) | \(\dfrac{d}{dx}f(x)\) |

|---|---|

| \(\sinh^{−1}x\) | \(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1+x^2}}\) |

| \(\cosh^{−1}x\) | \(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{x^2−1}}\) |

| \(\tanh^{−1}x\) | \(\dfrac{1}{1−x^2}\) |

| \(\coth^{−1}x\) | \(\dfrac{1}{1−x^2}\) |

| \(\text{sech}^{−1}x\) | \(\dfrac{−1}{x\sqrt{1−x^2}}\) |

| \(\text{csch}^{−1}x\) | \(\dfrac{−1}{|x|\sqrt{1+x^2}}\) |

Note that the derivatives of \(\tanh^{−1}x\) and \(\coth^{−1}x\) are the same. Thus, when we integrate \(1/(1−x^2)\), we need to select the proper antiderivative based on the domain of the functions and the values of \(x\). Integration formulas involving the inverse hyperbolic functions are summarized as follows.

\[\int \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1+u^2}}du=\sinh^{−1}u+C \nonumber \]

\[\int \dfrac{1}{u\sqrt{1−u^2}}du=−\text{sech}^{−1}|u|+C \nonumber \]

\[\int \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{u^2−1}}du=\cosh^{−1}u+C \nonumber \]

\[\int \dfrac{1}{u\sqrt{1+u^2}}du=−\text{csch}^{−1}|u|+C \nonumber \]

\[\int \dfrac{1}{1−u^2}du=\begin{cases}\tanh^{−1}u+C & \text{if }|u|<1\\ \coth^{−1}u+C & \text{if }|u|>1\end{cases} \nonumber \]

Evaluate the following derivatives:

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\sinh^{−1}\left(\dfrac{x}{3}\right)\right)\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\tanh^{−1}x\right)^2\)

Solution

Using the formulas in Table \(\PageIndex{3}\) and the chain rule, we obtain the following results:

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sinh^{−1}(\dfrac{x}{3}))=\dfrac{1}{3\sqrt{1+\dfrac{x^2}{9}}}=\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{9+x^2}}\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\tanh^{−1}x)^2=\dfrac{2(\tanh^{−1}x)}{1−x^2}\)

Evaluate the following derivatives:

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\cosh^{−1}(3x))\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\coth^{−1}x)^3\)

- Hint

-

Use the formulas in Table \(\PageIndex{3}\) and apply the chain rule as necessary.

- Answer a

-

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\cosh^{−1}(3x))=\dfrac{3}{\sqrt{9x^2−1}} \)

- Answer b

-

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\coth^{−1}x)^3=\dfrac{3(\coth^{−1}x)^2}{1−x^2} \)

Evaluate the following integrals:

- \(\displaystyle \int \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{4x^2−1}}dx\)

- \(\displaystyle \int \dfrac{1}{2x\sqrt{1−9x^2}}dx\)

Solution

We can use \(u\)-substitution in both cases.

Let \(u=2x\). Then, \(du=2\,dx\) and we have

\[\begin{align*} \int \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{4x^2−1}}\,dx &=\int \dfrac{1}{2\sqrt{u^2−1}}\,du \\[4pt] &=\dfrac{1}{2}\cosh^{−1}u+C \\[4pt] &=\dfrac{1}{2}\cosh^{−1}(2x)+C. \end{align*} \nonumber \]

Let \(u=3x.\) Then, \(du=3\,dx\) and we obtain

\[\begin{align*} \int \dfrac{1}{2x\sqrt{1−9x^2}}dx &=\dfrac{1}{2}\int \dfrac{1}{u\sqrt{1−u^2}}du \\[4pt] &=−\dfrac{1}{2}\text{sech}^{−1}|u|+C \\[4pt] &=−\dfrac{1}{2}\text{sech}^{−1}|3x|+C \end{align*}\]

Evaluate the following integrals:

- \(\displaystyle \int \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{x^2−4}}dx,x>2\)

- \(\displaystyle \int \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1−e^{2x}}}dx\)

- Hint

-

Use the formulas above and apply \(u\)-substitution as necessary.

- Answer a

-

\(\displaystyle \int \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{x^2−4}}dx=\cosh^{−1}(\dfrac{x}{2})+C\)

- Answer b

-

\( \displaystyle \int \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1−e^{2x}}}dx=−\text{sech}^{−1}(e^x)+C\)

Applications

One physical application of hyperbolic functions involves hanging cables. If a cable of uniform density is suspended between two supports without any load other than its own weight, the cable forms a curve called a catenary. High-voltage power lines, chains hanging between two posts, and strands of a spider’s web all form catenaries. The following figure shows chains hanging from a row of posts.

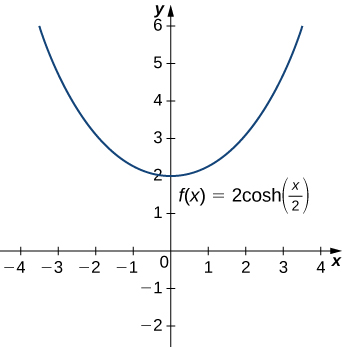

Hyperbolic functions can be used to model catenaries. Specifically, functions of the form \(y=a\cdot \cosh(x/a)\) are catenaries. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows the graph of \(y=2\cosh(x/2)\).

Assume a hanging cable has the shape \(10\cosh(x/10)\) for \(−15≤x≤15\), where \(x\) is measured in feet. Determine the length of the cable (in feet).

Solution

Recall from Section 6.4 that the formula for arc length is

\[\underbrace{\int ^b_a\sqrt{1+[f′(x)]^2}dx}_{\text{Arc Length}}. \nonumber \]

We have \(f(x)=10 \cosh(x/10)\), so \(f′(x)=\sinh(x/10)\). Then the arc length is

\[\int ^b_a\sqrt{1+[f′(x)]^2}dx=\int ^{15}_{−15}\sqrt{1+\sinh^2 \left(\dfrac{x}{10}\right)}dx. \nonumber \]

Now recall that

\[1+\sinh^2x=\cosh^2x, \nonumber \]

so we have

\[\begin{align*} \text{Arc Length} &= \int ^{15}_{−15}\sqrt{1+\sinh^2 \left(\dfrac{x}{10}\right)}dx \\[4pt] &=\int ^{15}_{−15}\cosh \left(\dfrac{x}{10}\right)dx \\[4pt] &= \left.10\sinh \left(\dfrac{x}{10}\right)\right|^{15}_{−15}\\[4pt] &=10\left[\sinh\left(\dfrac{3}{2}\right)−\sinh\left(−\dfrac{3}{2}\right)\right]\\[4pt] &=20\sinh \left(\dfrac{3}{2}\right) \\[4pt] &≈42.586\,\text{ft.} \end{align*}\]

Assume a hanging cable has the shape \(15 \cosh (x/15)\) for \(−20≤x≤20\). Determine the length of the cable (in feet).

- Answer

-

\(52.95\) ft

Key Concepts

- Hyperbolic functions are defined in terms of exponential functions.

- Term-by-term differentiation yields differentiation formulas for the hyperbolic functions. These differentiation formulas give rise, in turn, to integration formulas.

- With appropriate range restrictions, the hyperbolic functions all have inverses.

- Implicit differentiation yields differentiation formulas for the inverse hyperbolic functions, which in turn give rise to integration formulas.

- The most common physical applications of hyperbolic functions are calculations involving catenaries.

Glossary

- catenary

- a curve in the shape of the function \(y=a\cdot\cosh(x/a)\) is a catenary; a cable of uniform density suspended between two supports assumes the shape of a catenary