9.2: Infinite Series

- Page ID

- 2563

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Explain the meaning of the sum of an infinite series.

- Calculate the sum of a geometric series.

- Evaluate a telescoping series.

We have seen that a sequence is an ordered set of terms. If you add these terms together, you get a series. In this section we define an infinite series and show how series are related to sequences. We also define what it means for a series to converge or diverge. We introduce one of the most important types of series: the geometric series. We will use geometric series in the next chapter to write certain functions as polynomials with an infinite number of terms. This process is important because it allows us to evaluate, differentiate, and integrate complicated functions by using polynomials that are easier to handle. We also discuss the harmonic series, arguably the most interesting divergent series because it just fails to converge.

Sums and Series

An infinite series is a sum of infinitely many terms and is written in the form

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞a_n=a_1+a_2+a_3+⋯.\)

But what does this mean? We cannot add an infinite number of terms in the same way we can add a finite number of terms. Instead, the value of an infinite series is defined in terms of the limit of partial sums. A partial sum of an infinite series is a finite sum of the form

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^ka_n=a_1+a_2+a_3+⋯+a_k.\)

To see how we use partial sums to evaluate infinite series, consider the following example. Suppose oil is seeping into a lake such that \( 1000\) gallons enters the lake the first week. During the second week, an additional \( 500\) gallons of oil enters the lake. The third week, \( 250\) more gallons enters the lake. Assume this pattern continues such that each week half as much oil enters the lake as did the previous week. If this continues forever, what can we say about the amount of oil in the lake? Will the amount of oil continue to get arbitrarily large, or is it possible that it approaches some finite amount? To answer this question, we look at the amount of oil in the lake after \( k\) weeks. Letting \( S_k\) denote the amount of oil in the lake (measured in thousands of gallons) after \( k\) weeks, we see that

\( S_1=1\)

\( S_2=1+0.5=1+\frac{1}{2}\)

\( S_3=1+0.5+0.25=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{4}\)

\( S_4=1+0.5+0.25+0.125=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{8}\)

\( S_5=1+0.5+0.25+0.125+0.0625=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{16}.\)

Looking at this pattern, we see that the amount of oil in the lake (in thousands of gallons) after \( k\) weeks is

\[ S_k=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{16}+⋯+\frac{1}{2^{k−1}}=\sum_{n=1}^k\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−1}. \nonumber \]

We are interested in what happens as \( k→∞.\) Symbolically, the amount of oil in the lake as \( k→∞\) is given by the infinite series

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−1}=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{16}+⋯. \nonumber \]

At the same time, as \( k→∞\), the amount of oil in the lake can be calculated by evaluating \(\displaystyle \lim_{k→∞}S_k\). Therefore, the behavior of the infinite series can be determined by looking at the behavior of the sequence of partial sums \( {S_k}\). If the sequence of partial sums \( {S_k}\) converges, we say that the infinite series converges, and its sum is given by \(\displaystyle \lim_{k→∞}S_k\). If the sequence \( {S_k}\) diverges, we say the infinite series diverges. We now turn our attention to determining the limit of this sequence \( {S_k}\).

First, simplifying some of these partial sums, we see that

\( S_1=1\)

\( S_2=1+\frac{1}{2}=\frac{3}{2}\)

\( S_3=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{4}=\frac{7}{4}\)

\( S_4=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{8}=\frac{15}{8}\)

\( S_5=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{16}=\frac{31}{16}.\)

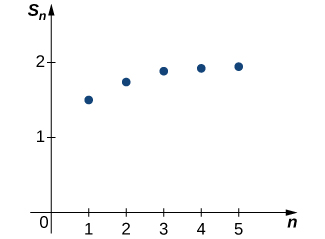

Plotting some of these values in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), it appears that the sequence \( {S_k}\) could be approaching 2.

Let’s look for more convincing evidence. In the following table, we list the values of \(S_k\) for several values of \(k\).

| \( k\) | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \( S_k\) | 1.9375 | 1.998 | 1.999939 | 1.999998 |

These data supply more evidence suggesting that the sequence \({S_k}\) converges to \(2\). Later we will provide an analytic argument that can be used to prove that \(\displaystyle \lim_{k→∞}S_k=2\). For now, we rely on the numerical and graphical data to convince ourselves that the sequence of partial sums does actually converge to \(2\). Since this sequence of partial sums converges to \(2\), we say the infinite series converges to \(2\) and write

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−1}=2.\nonumber \]

Returning to the question about the oil in the lake, since this infinite series converges to \(2\), we conclude that the amount of oil in the lake will get arbitrarily close to \(2000\) gallons as the amount of time gets sufficiently large.

This series is an example of a geometric series. We discuss geometric series in more detail later in this section. First, we summarize what it means for an infinite series to converge.

An infinite series is an expression of the form

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞a_n=a_1+a_2+a_3+⋯. \nonumber \]

For each positive integer \(k\), the sum

\[S_k=\sum_{n=1}^ka_n=a_1+a_2+a_3+⋯+a_k \nonumber \]

is called the \(k^{\text{th}}\) partial sum of the infinite series. The partial sums form a sequence \({S_k}\). If the sequence of partial sums converges to a real number \(S\), the infinite series converges. If we can describe the convergence of a series to \(S\), we call \(S\) the sum of the series, and we write

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞a_n=S. \nonumber \]

If the sequence of partial sums diverges, we have the divergence of a series.

Note that the index for a series need not begin with \(n=1\) but can begin with any value. For example, the series

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−1} \nonumber \]

can also be written as

\[\sum_{n=0}^∞\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^n\; \text{or}\; \sum_{n=5}^∞\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−5}. \nonumber \]

Often it is convenient for the index to begin at \(1\), so if for some reason it begins at a different value, we can re-index by making a change of variables. For example, consider the series

\[ \sum_{n=2}^∞\frac{1}{n^2}. \nonumber \]

By introducing the variable \(m=n−1\), so that \(n=m+1,\) we can rewrite the series as

\[ \sum_{m=1}^∞\frac{1}{(m+1)^2}. \nonumber \]

For each of the following series, use the sequence of partial sums to determine whether the series converges or diverges.

- \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{n}{n+1}\)

- \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞(−1)^n\)

- \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{1}{n(n+1)}\)

Solution

a. The sequence of partial sums \({S_k}\) satisfies

\(S_1=\dfrac{1}{2}\)

\(S_2=\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{2}{3}\)

\(S_3=\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{2}{3}+\dfrac{3}{4}\)

\(S_4=\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{2}{3}+\dfrac{3}{4}+\dfrac{4}{5}\).

Notice that each term added is greater than \(1/2\). As a result, we see that

\(S_1=\dfrac{1}{2}\)

\(S_2=\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{2}{3}>\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{2}=2\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)\)

\(S_3=\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{2}{3}+\dfrac{3}{4}>\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{2}=3\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)\)

\(S_4=\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{2}{3}+\dfrac{3}{4}+\dfrac{4}{5}>\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{2}=4\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right).\)

From this pattern we can see that \(S_k>k\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\) for every integer \(k\). Therefore, \({S_k}\) is unbounded and consequently, diverges. Therefore, the infinite series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{n}{n+1}\) diverges.

b. The sequence of partial sums \({S_k}\) satisfies

\(S_1=−1\)

\(S_2=−1+1=0\)

\(S_3=−1+1−1=−1\)

\(S_4=−1+1−1+1=0.\)

From this pattern we can see the sequence of partial sums is

\[{S_k}={−1,0,−1,0,…}. \nonumber \]

Since this sequence diverges, the infinite series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}(−1)^n\) diverges.

c. The sequence of partial sums \( {S_k}\) satisfies

\( S_1=\dfrac{1}{1⋅2}=\dfrac{1}{2}\)

\( S_2=\dfrac{1}{1⋅2}+\dfrac{1}{2⋅3}=\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{6}=\dfrac{2}{3}\)

\( S_3=\dfrac{1}{1⋅2}+\dfrac{1}{2⋅3}+\dfrac{1}{3⋅4}=\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{6}+\dfrac{1}{12}=\dfrac{3}{4}\)

\( S_4=\dfrac{1}{1⋅2}+\dfrac{1}{2⋅3}+\dfrac{1}{3⋅4}+\dfrac{1}{4⋅5}=\dfrac{4}{5}\)

\( S_5=\dfrac{1}{1⋅2}+\dfrac{1}{2⋅3}+\dfrac{1}{3⋅4}+\dfrac{1}{4⋅5}+\dfrac{1}{5⋅6}=\dfrac{5}{6}.\)

From this pattern, we can see that the \( k^{\text{th}}\) partial sum is given by the explicit formula

\[ S_k=\frac{k}{k+1} \nonumber \].

Since \( k/(k+1)→1,\) we conclude that the sequence of partial sums converges, and therefore the infinite series converges to \( 1\). We have

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{1}{n(n+1)}=1. \nonumber \]

Determine whether the series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{n+1}{n}\) converges or diverges.

- Hint

-

Look at the sequence of partial sums.

- Answer

-

The series diverges because the \( k^{\text{th}}\) partial sum \( S_k>k\).

The Harmonic Series

A useful series to know about is the harmonic series. The harmonic series is defined as

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{1}{n}=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{4}+⋯. \nonumber \]

This series is interesting because it diverges, but it diverges very slowly. By this we mean that the terms in the sequence of partial sums \( {S_k}\) approach infinity, but do so very slowly. We will show that the series diverges, but first we illustrate the slow growth of the terms in the sequence \( {S_k}\) in the following table.

| \( k\) | 10 | 100 | 1000 | 10,00 | 100,000 | 1,000,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \( S_k\) | 2.92897 | 5.18738 | 7.48547 | 9.78761 | 12.09015 | 14.39273 |

Even after \( 1,000,000\) terms, the partial sum is still relatively small. From this table, it is not clear that this series actually diverges. However, we can show analytically that the sequence of partial sums diverges, and therefore the series diverges.

To show that the sequence of partial sums diverges, we show that the sequence of partial sums is unbounded. We begin by writing the first several partial sums:

\( S_1=1\)

\( S_2=1+\dfrac{1}{2}\)

\( S_3=1+\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{3}\)

\( S_4=1+\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{3}+\dfrac{1}{4}\).

Notice that for the last two terms in \( S_4\),

\[ \frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{4}>\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{4} \nonumber \]

Therefore, we conclude that

\[ S_4>1+\frac{1}{2}+\left(\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{4}\right)=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2}=1+2\left(\frac{1}{2}\right). \nonumber \]

Using the same idea for \( S_8\), we see that

\(\displaystyle S_8=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{5}+\frac{1}{6}+\frac{1}{7}+\frac{1}{8}>1+\frac{1}{2}+\left(\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{4}\right)+\left(\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{8}\right)=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2}=1+3\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\).

From this pattern, we see that \( S_1=1, S_2=1+1/2, S_4>1+2(1/2),\) and \( S_8>1+3(1/2)\). More generally, it can be shown that \( S_{2^j}>1+j(1/2)\) for all \( j>1\). Since \( 1+j(1/2)→∞,\) we conclude that the sequence \( {S_k}\) is unbounded and therefore diverges. In the previous section, we stated that convergent sequences are bounded. Consequently, since \( {S_k}\) is unbounded, it diverges. Thus, the harmonic series diverges.

Algebraic Properties of Convergent Series

Since the sum of a convergent infinite series is defined as a limit of a sequence, the algebraic properties for series listed below follow directly from the algebraic properties for sequences.

Let \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞ a_n\) and \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞ b_n\) be convergent series. Then the following algebraic properties hold.

i. The series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞(a_n+b_n)\) converges, and \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}(a_n+b_n)=\sum^∞_{n=1}a_n+\sum^∞_{n=1}b_n.\) (Sum Rule)

ii. The series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞(a_n−b_n)\) converges, and \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}(a_n−b_n)=\sum^∞_{n=1}a_n−\sum^∞_{n=1}b_n.\) (Difference Rule)

iii. For any real number \( c\), the series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞ca_n\) converges, and \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}ca_n=c\sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\). (Constant Multiple Rule)

Evaluate \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\left[\frac{3}{n(n+1)}+\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−2}\right].\)

Solution

We showed earlier that

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{1}{n(n+1)} = 1 \nonumber \]

and

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−1}=2. \nonumber \]

Since both of those series converge, we can apply the properties of Note \(\PageIndex{1}\) to evaluate

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞\left[\frac{3}{n(n+1)}+\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−2}\right]. \nonumber \]

Using the sum rule, write

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\left[\frac{3}{n(n+1)}+\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−2}\right]=\sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{3}{n(n+1)}+\sum_{n=1}^∞\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−2}.\)

Then, using the constant multiple rule and the sums above, we can conclude that

\(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{3}{n(n+1)}+\sum^∞_{n=1}\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−2}=3\sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{1}{n(n+1)}+\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{−1}\sum^∞_{n=1}\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−1}=3(1)+\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{−1}(2)=3+2(2)=7.\)

Evaluate \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{5}{2^{n−1}}\).

- Hint

-

Rewrite as \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}5\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−1}\).

- Answer

-

10

Geometric Series

A geometric series is any series that we can write in the form

\[ a+ar+ar^2+ar^3+⋯=\sum_{n=1}^∞ar^{n−1}. \nonumber \]

Because the ratio of each term in this series to the previous term is \(r\), the number \(r\) is called the ratio. We refer to \(a\) as the initial term because it is the first term in the series. For example, the series

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n−1}=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{8}+⋯ \nonumber \]

is a geometric series with initial term \( a=1\) and ratio \( r=1/2\).

In general, when does a geometric series converge? Consider the geometric series

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞ar^{n−1} \nonumber \]

when \( a>0\). Its sequence of partial sums \( {S_k}\) is given by

\[S_k=\sum_{n=1}^kar^{n−1}=a+ar+ar^2+⋯+ar^{k−1}. \nonumber \]

Consider the case when \( r=1.\) In that case,

\[S_k=a+a(1)+a(1)^2+⋯+a(1)^{k−1}=ak. \nonumber \]

Since \( a>0\), we know \( ak→∞\) as \( k→∞\). Therefore, the sequence of partial sums is unbounded and thus diverges. Consequently, the infinite series diverges for \( r=1\). For \( r≠1\), to find the limit of \( {S_k}\), multiply Equation by \( 1−r\). Doing so, we see that

\[ (1−r)S_k=a(1−r)(1+r+r^2+r^3+⋯+r^{k−1})=a[(1+r+r^2+r^3+⋯+r^{k−1})−(r+r^2+r^3+⋯+r^k)]=a(1−r^k). \nonumber \]

All the other terms cancel out.

Therefore,

\( S_k=\dfrac{a(1−r^k)}{1−r}\) for \( r≠1\).

From our discussion in the previous section, we know that the geometric sequence \( r^k→0\) if \( |r|<1\) and that \( r^k\) diverges if \( |r|>1\) or \( r=±1\). Therefore, for \( |r|<1, S_k→\dfrac{a}{1−r}\) and we have

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞ar^{n−1}=\frac{a}{1−r}\; \text{if}\; |r|<1. \nonumber \]

If \( |r|≥1, \, S_k\) diverges, and therefore

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞ar^{n−1} \; \text{diverges if}\; |r|≥1. \nonumber \]

A geometric series is a series of the form

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞ar^{n−1}=a+ar+ar^2+ar^3+⋯. \label{geoseriesdef} \]

If \( |r|<1\), the series converges, and

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞ar^{n−1}=\frac{a}{1−r}\; \text{for}\; |r|<1. \nonumber \]

If \( |r|≥1\), the series diverges.

Geometric series sometimes appear in slightly different forms. For example, sometimes the index begins at a value other than \( n=1\) or the exponent involves a linear expression for \( n\) other than \( n−1\). As long as we can rewrite the series in the form given by Equation \ref{geoseriesdef}, it is a geometric series. For example, consider the series

\[\sum_{n=0}^∞\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{n+2}. \nonumber \]

To see that this is a geometric series, we write out the first several terms:

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^∞\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{n+2}=\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^2+\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^3+\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^4+⋯=\frac{4}{9}+\frac{4}{9}⋅\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)+\frac{4}{9}⋅\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^2+⋯.\)

We see that the initial term is \( a=4/9\) and the ratio is \( r=2/3.\) Therefore, the series can be written as

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{4}{9}⋅\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{n−1}.\)

Since \( r=2/3<1\), this series converges, and its sum is given by

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{4}{9}⋅\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{n−1}=\frac{4/9}{1−2/3}=\frac{4}{3}.\)

Determine whether each of the following geometric series converges or diverges, and if it converges, find its sum.

- \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{(−3)^{n+1}}{4^{n−1}}\)

- \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}e^{2n}\)

Solution

a. Writing out the first several terms in the series, we have

\[\begin{align*} \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{(−3)^{n+1}}{4^{n−1}} &= \frac{(−3)^2}{4^0}+\frac{(−3)^3}{4}+\frac{(−3)^4}{4^2}+⋯ \\[4pt] &=(−3)^2+(−3)^2⋅\left(\frac{−3}{4}\right)+(−3)^2⋅\left(\frac{−3}{4}\right)^2+⋯ \\[4pt] &=9+9⋅\left(\frac{−3}{4}\right)+9⋅\left(\frac{−3}{4}\right)^2+⋯. \end{align*}\]

The initial term \( a=−3\) and the ratio \( r=−3/4\). Since \( |r|=3/4<1\), the series converges to

\[ \frac{9}{1−(−3/4)}=\frac{9}{7/4}=\frac{36}{7}. \nonumber \]

b. Writing this series as

\[ e^2\sum_{n=1}^∞(e^2)^{n−1} \nonumber \]

we can see that this is a geometric series where \( r=e^2>1.\) Therefore, the series diverges.

Determine whether the series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\left(\frac{−2}{5}\right)^{n−1}\) converges or diverges. If it converges, find its sum.

- Hint

-

\( r=−2/5\)

- Answer

-

\( 5/7\)

We now turn our attention to a nice application of geometric series. We show how they can be used to write repeating decimals as fractions of integers.

Use a geometric series to write \( 3.\bar{26}\) as a fraction of integers.

Solution

Since \( 3.\bar{26}—=3.262626…,\) first we write

\[\begin{align*} 3.262626… &= 3+\frac{26}{100}+\frac{26}{10,000}+\frac{26}{100,000}+⋯ \\[4pt] &=3+\frac{26}{10^2}+\frac{26}{10^4}+\frac{26}{10^6}+⋯. \end{align*}\]

Ignoring the term 3, the rest of this expression is a geometric series with initial term \( a=26/10^2\) and ratio \( r=1/10^2.\) Therefore, the sum of this series is

\[ \frac{26/10^2}{1−(1/10^2)}=\frac{26/10^2}{99/10^2}=\frac{26}{99}. \nonumber \]

Thus,

\( 3.262626…=3+\frac{26}{99}=\frac{323}{99}\).

Write \( 5.2\bar{7}\) as a fraction of integers.

- Hint

-

By expressing this number as a series, find a geometric series with initial term \( a=7/100\) and ratio \( r=1/10\).

- Answer

-

\( 475/90\)

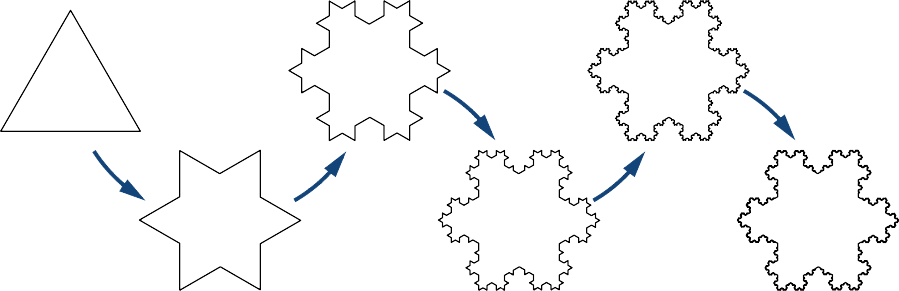

Define a sequence of figures \( \{F_n\}\) recursively as follows (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Let \( F_0\) be an equilateral triangle with sides of length \( 1\). For \( n≥1\), let \( F_n\) be the curve created by removing the middle third of each side of \( F_{n−1}\) and replacing it with an equilateral triangle pointing outward. The limiting figure as \( n→∞\) is known as Koch’s snowflake.

- Find the length \( L_n\) of the perimeter of \( F_n\). Evaluate \(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}L_n\) to find the length of the perimeter of Koch’s snowflake.

- Find the area \( A_n\) of figure \( F_n\). Evaluate \(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}A_n\) to find the area of Koch’s snowflake.

Solution

a. Let \( N_n\) denote the number of sides of figure \( F_n\). Since \( F_0\) is a triangle, \( N_0=3\). Let \(l_n\) denote the length of each side of \( F_n\). Since \( F_0\) is an equilateral triangle with sides of length \( l_0=1\), we now need to determine \( N_1\) and \( l_1\). Since \( F_1\) is created by removing the middle third of each side and replacing that line segment with two line segments, for each side of \( F_0\), we get four sides in \( F_1\). Therefore, the number of sides for \( F_1\) is

\( N_1=4⋅3\).

Since the length of each of these new line segments is \( 1/3\) the length of the line segments in \( F_0\), the length of the line segments for \( F_1\) is given by

\( l_1=\frac{1}{3}⋅1=\frac{1}{3}\).

Similarly, for \( F_2\), since the middle third of each side of \( F_1\) is removed and replaced with two line segments, the number of sides in \( F_2\) is given by

\( N_2=4N_1=4(4⋅3)=4^2⋅3.\)

Since the length of each of these sides is \( 1/3\) the length of the sides of \( F_1\), the length of each side of figure \( F_2\) is given by

\( l_2=\frac{1}{3}⋅l_1=\frac{1}{3}⋅\frac{1}{3}=\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^2\).

More generally, since \( F_n\) is created by removing the middle third of each side of \( F_{n−1}\) and replacing that line segment with two line segments of length \( \frac{1}{3}l_{n−1}\) in the shape of an equilateral triangle, we know that \( N_n=4N_{n−1}\) and \( l_n=\dfrac{l_{n−1}}{3}\). Therefore, the number of sides of figure \( F_n\) is

\( N_n=4^n⋅3\)

and the length of each side is

\[ l_n=\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^n. \nonumber \]

Therefore, to calculate the perimeter of \( F_n\), we multiply the number of sides \( N_n\) and the length of each side \( l_n\). We conclude that the perimeter of \( F_n\) is given by

\[ L_n=N_n⋅l_n=3⋅\left(\frac{4}{3}\right)^n \nonumber \]

Therefore, the length of the perimeter of Koch’s snowflake is

\[ L=\lim_{n→∞}L_n=∞. \nonumber \]

b. Let \( T_n\) denote the area of each new triangle created when forming \( F_n\). For \( n=0, T_0\) is the area of the original equilateral triangle. Therefore, \( T_0=A_0=\sqrt{3}/4\). For \( n≥1\), since the lengths of the sides of the new triangle are \( 1/3\) the length of the sides of \( F_{n−1}\), we have

\[ T_n=\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^2⋅T_{n−1}=\frac{1}{9}⋅T_{n−1}. \nonumber \]

Therefore, \( T_n=\left(\frac{1}{9}\right)^n⋅\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\). Since a new triangle is formed on each side of \( F_{n−1}\),

\[ A_n=A_{n−1}+N_{n−1}⋅T_n=A_{n−1}+(3⋅4_{n−1})⋅\left(\frac{1}{9}\right)^n⋅\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}=A_{n−1}+\frac{3}{4}⋅\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^n⋅\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}. \nonumber \]

Writing out the first few terms \( A_0,A_1,A_2,\) we see that

\( A_0=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\)

\(A_1=A_0+\frac{3}{4}⋅\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)⋅\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}+\frac{3}{4}⋅\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)⋅\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\left[1+\frac{3}{4}⋅\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)\right]\)

\( A_2=A_1+\frac{3}{4}⋅(\frac{4}{9})^2⋅\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\left[1+\frac{3}{4}⋅\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)\right]+\frac{3}{4}⋅\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^2⋅\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}[1+\frac{3}{4}⋅(\frac{4}{9})+\frac{3}{4}⋅\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^2]\).

More generally,

\( A_n=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\left[1+\frac{3}{4}\left(\frac{4}{9}+\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^2+⋯+\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^n\right)\right]\).

Factoring \( 4/9\) out of each term inside the inner parentheses, we rewrite our expression as

\( A_n=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\left[1+\frac{1}{3}\left(1+\frac{4}{9}+\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^2+⋯+\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^{n−1}\right)\right]\).

The expression \( 1+\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)+\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^2+⋯+\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^{n−1}\) is a geometric sum. As shown earlier, this sum satisfies

\( 1+\frac{4}{9}+\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^2+⋯+\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^{n−1}=\dfrac{1−(4/9)^n}{1−(4/9)}.\)

Substituting this expression into the expression above and simplifying, we conclude that

\[ A_n=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\left[1+\frac{1}{3}(\frac{1−(4/9)^n}{1−(4/9)})\right]=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\left[\frac{8}{5}−\frac{3}{5}\left(\frac{4}{9}\right)^n\right]. \nonumber \]

Therefore, the area of Koch’s snowflake is

\(\displaystyle A=\lim_{n→∞}A_n=\frac{2\sqrt{3}}{5}.\)

Analysis

The Koch snowflake is interesting because it has finite area, yet infinite perimeter. Although at first this may seem impossible, recall that you have seen similar examples earlier in the text. For example, consider the region bounded by the curve \( y=1/x^2\) and the \( x\)-axis on the interval \( [1,∞).\) Since the improper integral

\[ ∫^∞_1\frac{1}{x^2}\,dx \nonumber \]

converges, the area of this region is finite, even though the perimeter is infinite.

Telescoping Series

Consider the series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{1}{n(n+1)}.\) We discussed this series in Example , showing that the series converges by writing out the first several partial sums \( S_1, \, S_2, \, …, \, S_6\) and noticing that they are all of the form \( S_k=\dfrac{k}{k+1}\). Here we use a different technique to show that this series converges. By using partial fractions, we can write

\[ \frac{1}{n(n+1)}=\frac{1}{n}−\frac{1}{n+1}. \nonumber \]

Therefore, the series can be written as

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\left[\frac{1}{n}−\frac{1}{n+1}\right]=\left(1-\frac{1}{2}\right)+\left(\frac{1}{2}−\frac{1}{3}\right)+\left(\frac{1}{3}−\frac{1}{4}\right)+⋯.\)

Writing out the first several terms in the sequence of partial sums \( {S_k},\) we see that

\( S_1=1−\frac{1}{2}\)

\( S_2=\left(1−\frac{1}{2}\right)+\left(\frac{1}{2}−\frac{1}{3}\right)=1−\frac{1}{3}\)

\( S_3=\left(1−\frac{1}{2}\right)+\left(\frac{1}{2}−\frac{1}{3}\right)+\left(\frac{1}{3}−\frac{1}{4}\right)=1−\frac{1}{4}\).

In general,

\( S_k=\left(1−\frac{1}{2}\right)+\left(\frac{1}{2}−\frac{1}{3}\right)+\left(\frac{1}{3}−\frac{1}{4}\right)+⋯+\left(\frac{1}{k}−\frac{1}{k+1}\right)=1−\dfrac{1}{k+1}\).

We notice that the middle terms cancel each other out, leaving only the first and last terms. In a sense, the series collapses like a spyglass with tubes that disappear into each other to shorten the telescope. For this reason, we call a series that has this property a telescoping series. For this series, since \( S_k=1−1/(k+1)\) and \( 1/(k+1)→0\) as \( k→∞\), the sequence of partial sums converges to \( 1\), and therefore the series converges to \( 1\).

A telescoping series is a series in which most of the terms cancel in each of the partial sums, leaving only some of the first terms and some of the last terms.

For example, any series of the form

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞[b_n−b_{n+1}]=(b_1−b_2)+(b_2−b_3)+(b_3−b_4)+⋯\)

is a telescoping series. We can see this by writing out some of the partial sums. In particular, we see that

\( S_1=b_1−b_2\)

\( S_2=(b_1−b_2)+(b_2−b_3)=b_1−b_3\)

\( S_3=(b_1−b_2)+(b_2−b_3)+(b_3−b_4)=b_1−b_4.\)

In general, the \( k^{\text{th}}\) partial sum of this series is

\( S_k=b_1−b_{k+1}\).

Since the \( k^{\text{th}}\) partial sum can be simplified to the difference of these two terms, the sequence of partial sums \( {S_k}\) will converge if and only if the sequence \( {b_{k+1}}\) converges. Moreover, if the sequence \( b_{k+1}\) converges to some finite number B, then the sequence of partial sums converges to \( b_1−B\), and therefore

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞[b_n−b_{n+1}]=b_1−B.\)

In the next example, we show how to use these ideas to analyze a telescoping series of this form.

Determine whether the telescoping series

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\left[\cos\left(\frac{1}{n}\right)−\cos\left(\frac{1}{n+1}\right)\right]\)

converges or diverges. If it converges, find its sum.

Solution

By writing out terms in the sequence of partial sums, we can see that

\( S_1=\cos(1)−\cos(\frac{1}{2})\)

\( S_2=(\cos(1)−\cos(\frac{1}{2}))+(\cos(\frac{1}{2})−\cos(\frac{1}{3}))=\cos(1)−\cos(\frac{1}{3})\)

\( S_3=(\cos(1)−\cos(\frac{1}{2}))+(\cos(\frac{1}{2})−\cos(\frac{1}{3}))+(\cos(\frac{1}{3})−\cos(\frac{1}{4}))\)

\( =\cos(1)−\cos(\frac{1}{4})\).

In general,

\( S_k=\cos(1)−\cos\left(\frac{1}{k+1}\right)\).

Since \( 1/(k+1)→0\) as \( k→∞\) and \( \cos x\) is a continuous function, \( \cos(1/(k+1))→\cos(0)=1\). Therefore, we conclude that \( S_k→\cos(1)−1\). The telescoping series converges and the sum is given by

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\left[\cos\left(\frac{1}{n}\right)−\cos\left(\frac{1}{n+1}\right)\right]=\cos(1)−1.\)

Determine whether \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}[e^{1/n}−e^{1/(n+1)}]\) converges or diverges. If it converges, find its sum.

- Hint

-

Write out the sequence of partial sums to see which terms cancel.

- Answer

-

\( e−1\)

We have shown that the harmonic series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{1}{n}\) diverges. Here we investigate the behavior of the partial sums \( S_k\) as \( k→∞.\) In particular, we show that they behave like the natural logarithm function by showing that there exists a constant \( γ\) such that

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^k\left(\frac{1}{n}−\ln k\right)→γ\) as \( k→∞.\)

This constant \( γ\) is known as Euler’s constant.

1. Let \(\displaystyle T_k=\sum_{n=1}^k\left(\frac{1}{n}−\ln k\right).\) Evaluate \( T_k\) for various values of \( k\).

2. For \( T_k\) as defined in part 1. show that the sequence \( {T_k}\) converges by using the following steps.

a. Show that the sequence \( {T_k}\) is monotone decreasing. (Hint: Show that \( \ln(1+1/k>1/(k+1))\)

b. Show that the sequence \( {T_k}\) is bounded below by zero. (Hint: Express \( \ln k\) as a definite integral.)

c. Use the Monotone Convergence Theorem to conclude that the sequence \( {T_k}\) converges. The limit \( γ\) is Euler’s constant.

3. Now estimate how far \( T_k\) is from \( γ\) for a given integer \( k\). Prove that for \( k≥1, 0<T_k−γ≤1/k\) by using the following steps.

a. Show that \( \ln(k+1)−\ln k<1/k.\)

b. Use the result from part a. to show that for any integer \( k\),

\[ T_k−T_{k+1}<\frac{1}{k}−\frac{1}{k+1}. \nonumber \]

c. For any integers \( k\) and \( j\) such that \( j>k\), express \( T_k−T_j\) as a telescoping sum by writing

\[ T_k−T_j=(T_k−T_{k+1})+(T_{k+1}−T_{k+2})+(T_{k+2}−T_{k+3})+⋯+(T_{j−1}−T_j). \nonumber \]

Use the result from part b. combined with this telescoping sum to conclude that

\[ T_k−T_j<\frac{1}{k}−\frac{1}{j}. \nonumber \]

a. Apply the limit to both sides of the inequality in part c. to conclude that

\[ T_k−γ≤\frac{1}{k}. \nonumber \]

e. Estimate \( γ\) to an accuracy of within 0.001.

Key Concepts

- Given the infinite series

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞a_n=a_1+a_2+a_3+⋯\)

and the corresponding sequence of partial sums \( {S_k}\) where

\(\displaystyle S_k=\sum_{n=1}^ka_n=a_1+a_2+a_3+⋯+a_k\),

the series converges if and only if the sequence \( {S_k}\) converges.

- The geometric series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}ar^{n−1}\) converges if \( |r|<1\) and diverges if \( |r|≥1.\) For \( |r|<1,\)

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞ar^{n−1}=\frac{a}{1−r}\).

- The harmonic series

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{1}{n}=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{3}+⋯\)

diverges.

- A series of the form \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞[b_n−b_{n+1}]=[b_1−b_2]+[b_2−b_3]+[b_3−b_4]+⋯+[b_n−b_{n+1}]+⋯\) is a telescoping series. The \( k^{\text{th}}\) partial sum of this series is given by \( S_k=b_1−b_{k+1}\). The series will converge if and only if \(\displaystyle \lim_{k→∞} b_{k+1}\) exists. In that case,

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞[b_n−b_{n+1}]=b_1−\lim_{k→∞}(b_{k+1})\).

Key Equations

- Harmonic series

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{1}{n}=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{4}+⋯\)

- Sum of a geometric series

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞ar^{n−1}=\frac{a}{1−r}\) for \( |r|<1\)

Glossary

- convergence of a series

- a series converges if the sequence of partial sums for that series converges

- divergence of a series

- a series diverges if the sequence of partial sums for that series diverges

- geometric series

- a geometric series is a series that can be written in the form

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞ar^{n−1}=a+ar+ar^2+ar^3+⋯\)

- harmonic series

- the harmonic series takes the form

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{1}{n}=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{3}+⋯\)

- infinite series

- an infinite series is an expression of the form

\(\displaystyle a_1+a_2+a_3+⋯=\sum_{n=1}^∞a_n\)

- partial sum

-

the \( k^{\text{th}}\) partial sum of the infinite series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) is the finite sum

\(\displaystyle S_k=\sum_{n=1}^ka_n=a_1+a_2+a_3+⋯+a_k\)

- telescoping series

- a telescoping series is one in which most of the terms cancel in each of the partial sums