10.3: Taylor and Maclaurin Series

- Page ID

- 2571

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Describe the procedure for finding a Taylor polynomial of a given order for a function.

- Explain the meaning and significance of Taylor’s theorem with remainder.

- Estimate the remainder for a Taylor series approximation of a given function.

In the previous two sections we discussed how to find power series representations for certain types of functions––specifically, functions related to geometric series. Here we discuss power series representations for other types of functions. In particular, we address the following questions: Which functions can be represented by power series and how do we find such representations? If we can find a power series representation for a particular function \(f\) and the series converges on some interval, how do we prove that the series actually converges to \(f\)?

Overview of Taylor/Maclaurin Series

Consider a function \(f\) that has a power series representation at \(x=a\). Then the series has the form

\[\sum_{n=0}^∞c_n(x−a)^n=c_0+c_1(x−a)+c_2(x−a)^2+ \dots. \label{eq1} \]

What should the coefficients be? For now, we ignore issues of convergence, but instead focus on what the series should be, if one exists. We return to discuss convergence later in this section. If the series Equation \ref{eq1} is a representation for \(f\) at \(x=a\), we certainly want the series to equal \(f(a)\) at \(x=a\). Evaluating the series at \(x=a\), we see that

\[\sum_{n=0}^∞c_n(x−a)^n=c_0+c_1(a−a)+c_2(a−a)^2+\dots=c_0.\label{eq2} \]

Thus, the series equals \(f(a)\) if the coefficient \(c_0=f(a)\). In addition, we would like the first derivative of the power series to equal \(f′(a)\) at \(x=a\). Differentiating Equation \ref{eq2} term-by-term, we see that

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}\left( \sum_{n=0}^∞c_n(x−a)^n \right)=c_1+2c_2(x−a)+3c_3(x−a)^2+\dots.\label{eq3} \]

Therefore, at \(x=a,\) the derivative is

\[ f′(a) =c_1+2c_2(a−a)+3c_3(a−a)^2+\dots=c_1.\label{eq4} \]

Therefore, the derivative of the series equals \(f′(a)\) if the coefficient \(c_1=f′(a).\) Continuing in this way, we look for coefficients \(c_n\) such that all the derivatives of the power series Equation \ref{eq4} will agree with all the corresponding derivatives of \(f\) at \(x=a\). The second and third derivatives of Equation \ref{eq3} are given by

\[\dfrac{d^2}{dx^2} \left(\sum_{n=0}^∞c_n(x−a)^n \right)=2c_2+3⋅2c_3(x−a)+4⋅3c_4(x−a)^2+\dots\label{eq5} \]

and

\[ \dfrac{d^3}{dx^3} \left( \sum_{n=0}^∞c_n(x−a)^n \right) =3⋅2c_3+4⋅3⋅2c_4(x−a)+5⋅4⋅3c_5(x−a)^2+⋯.\label{eq6} \]

Therefore, at \(x=a\), the second and third derivatives

\[ f''(a) =2c_2+3⋅2c_3(a−a)+4⋅3c_4(a−a)^2+\dots=2c_2\label{eq7} \]

and

\[ f'''(a)\ =3⋅2c_3+4⋅3⋅2c_4(a−a)+5⋅4⋅3c_5(a−a)^2+\dots =3⋅2c_3\label{eq8} \]

equal \(f''(a)\) and \(f'''(a)\), respectively, if \(c_2=\dfrac{f''(a)}{2}\) and \(c_3=\dfrac{f'''(a)}{3⋅2}\). More generally, we see that if \(f\) has a power series representation at \(x=a\), then the coefficients should be given by \(c_n=\dfrac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}\). That is, the series should be

\[\sum_{n=0}^∞\dfrac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}(x−a)^n=f(a)+f′(a)(x−a)+\dfrac{f''(a)}{2!}(x−a)^2+\dfrac{f'''(a)}{3!}(x−a)^3+⋯ \nonumber \]

This power series for \(f\) is known as the Taylor series for \(f\) at \(a.\) If \(a=0\), then this series is known as the Maclaurin series for \(f\).

If \(f\) has derivatives of all orders at \(x=a\), then the Taylor series for the function \(f\) at \(a\) is

\[\sum_{n=0}^∞\dfrac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}(x−a)^n=f(a)+f′(a)(x−a)+\dfrac{f''(a)}{2!}(x−a)^2+⋯+\dfrac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}(x−a)^n+⋯ \nonumber \]

The Taylor series for \(f\) at 0 is known as the Maclaurin series for \(f\).

Later in this section, we will show examples of finding Taylor series and discuss conditions under which the Taylor series for a function will converge to that function. Here, we state an important result. Recall that power series representations are unique. Therefore, if a function \(f\) has a power series at \(a\), then it must be the Taylor series for \(f\) at \(a\).

If a function \(f\) has a power series at \(a\) that converges to \(f\) on some open interval containing \(a\), then that power series is the Taylor series for \(f\) at \(a\).

The proof follows directly from that discussed previously.

To determine if a Taylor series converges, we need to look at its sequence of partial sums. These partial sums are finite polynomials, known as Taylor polynomials.

Taylor Polynomials

The \(n^{\text{th}}\) partial sum of the Taylor series for a function \(f\) at \(a\) is known as the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomial. For example, the 0th, 1st, 2nd, and 3rd partial sums of the Taylor series are given by

\[\begin{align*} p_0(x) &=f(a) \\[4pt] p_1(x) &=f(a)+f′(a)(x−a) \\[4pt]p_2(x) &=f(a)+f′(a)(x−a)+\dfrac{f''(a)}{2!}(x−a)^2\ \\[4pt]p_3(x) &=f(a)+f′(a)(x−a)+\dfrac{f''(a)}{2!}(x−a)^2+\dfrac{f'''(a)}{3!}(x−a)^3 \end{align*}\]

respectively. These partial sums are known as the 0th, 1st, 2nd, and 3rd degree Taylor polynomials of \(f\) at \(a\), respectively. If \(a=0\), then these polynomials are known as Maclaurin polynomials for \(f\). We now provide a formal definition of Taylor and Maclaurin polynomials for a function \(f\).

If \(f\) has \(n\) derivatives at \(x=a\), then the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomial of \(f\) at \(a\) is

\[p_n(x)=f(a)+f′(a)(x−a)+\dfrac{f''(a)}{2!}(x−a)^2+\dfrac{f'''(a)}{3!}(x−a)^3+⋯+\dfrac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}(x−a)^n. \nonumber \]

The \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomial for \(f\) at \(0\) is known as the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Maclaurin polynomial for \(f\).

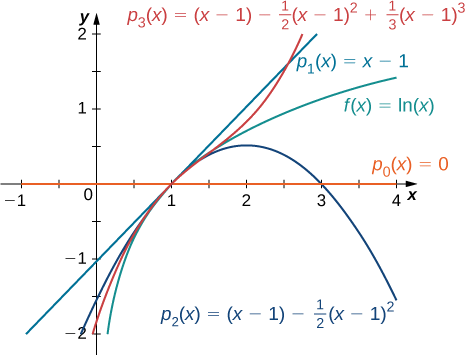

We now show how to use this definition to find several Taylor polynomials for \(f(x)=\ln x\) at \(x=1\).

Find the Taylor polynomials \(p_0,p_1,p_2\) and \(p_3\) for \(f(x)=\ln x\) at \(x=1\). Use a graphing utility to compare the graph of \(f\) with the graphs of \(p_0,p_1,p_2\) and \(p_3\).

Solution

To find these Taylor polynomials, we need to evaluate \(f\) and its first three derivatives at \(x=1\).

\[\begin{align*} f(x)&=\ln x & f(1)&=0\\[5pt]

f′(x)&=\dfrac{1}{x} & f′(1)&=1\\[5pt]

f''(x)&=−\dfrac{1}{x^2} & f''(1)&=−1\\[5pt]

f'''(x)&=\dfrac{2}{x^3} & f'''(1)&=2\end{align*}\]

Therefore,

\[\begin{align*} p_0(x) &= f(1)=0,\\[4pt]p_1(x) &=f(1)+f′(1)(x−1) =x−1,\\[4pt]p_2(x) &=f(1)+f′(1)(x−1)+\dfrac{f''(1)}{2}(x−1)^2 = (x−1)−\dfrac{1}{2}(x−1)^2 \\[4pt]p_3(x) &=f(1)+f′(1)(x−1)+\dfrac{f''(1)}{2}(x−1)^2+\dfrac{f'''(1)}{3!}(x−1)^3=(x−1)−\dfrac{1}{2}(x−1)^2+\dfrac{1}{3}(x−1)^3 \end{align*}\]

The graphs of \(y=f(x)\) and the first three Taylor polynomials are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Find the Taylor polynomials \(p_0,p_1,p_2\) and \(p_3\) for \(f(x)=\dfrac{1}{x^2}\) at \(x=1\).

- Hint

-

Find the first three derivatives of \(f\) and evaluate them at \(x=1.\)

- Answer

-

\[ \begin{align*} p_0(x)&=1\\[5pt]

p_1(x)&=1−2(x−1)\\[5pt]

p_2(x)&=1−2(x−1)+3(x−1)^2\\[5pt]

p_3(x)&=1−2(x−1)+3(x−1)^2−4(x−1)^3\end{align*}\]

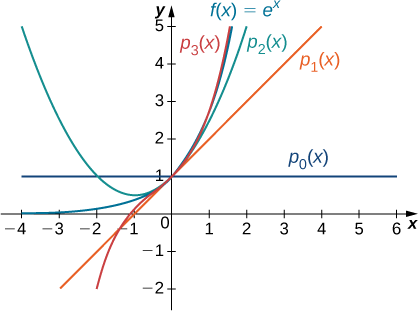

We now show how to find Maclaurin polynomials for \(e^x, \sin x,\) and \(\cos x\). As stated above, Maclaurin polynomials are Taylor polynomials centered at zero.

For each of the following functions, find formulas for the Maclaurin polynomials \(p_0,p_1,p_2\) and \(p_3\). Find a formula for the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Maclaurin polynomial and write it using sigma notation. Use a graphing utility to compare the graphs of \(p_0,p_1,p_2\) and \(p_3\) with \(f\).

- \(f(x)=e^x\)

- \(f(x)=\sin x\)

- \(f(x)=\cos x\)

Solution

Since \(f(x)=e^x\),we know that \(f(x)=f′(x)=f''(x)=⋯=f^{(n)}(x)=e^x\) for all positive integers \(n\). Therefore,

\[f(0)=f′(0)=f''(0)=⋯=f^{(n)}(0)=1 \nonumber \]

for all positive integers \(n\). Therefore, we have

\(\begin{align*} p_0(x)&=f(0)=1,\\[5pt]

p_1(x)&=f(0)+f′(0)x=1+x,\\[5pt]

p_2(x)&=f(0)+f′(0)x+\dfrac{f''(0)}{2!}x^2=1+x+\dfrac{1}{2}x^2,\\[5pt]

p_3(x)&=f(0)+f′(0)x+\dfrac{f''(0)}{2}x^2+\dfrac{f'''(0)}{3!}x^3=1+x+\dfrac{1}{2}x^2+\dfrac{1}{3!}x^3,\end{align*}\)

\(\begin{align*} p_n(x)&=f(0)+f′(0)x+\dfrac{f''(0)}{2}x^2+\dfrac{f'''(0)}{3!}x^3+⋯+\dfrac{f^{(n)}(0)}{n!}x^n\\[5pt]

&=1+x+\dfrac{x^2}{2!}+\dfrac{x^3}{3!}+⋯+\dfrac{x^n}{n!}\\[5pt]

&=\sum_{k=0}^n\dfrac{x^k}{k!}\end{align*}\).

The function and the first three Maclaurin polynomials are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

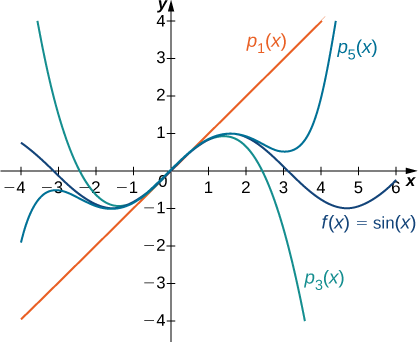

b. For \(f(x)=\sin x\), the values of the function and its first four derivatives at \(x=0\) are given as follows:

\[\begin{align*} f(x)&=\sin x & f(0)&=0\\[5pt]

f′(x)&=\cos x & f′(0)&=1\\[5pt]

f''(x)&=−\sin x & f''(0)&=0\\[5pt]

f'''(x)&=−\cos x & f'''(0)&=−1\\[5pt]

f^{(4)}(x)&=\sin x & f^{(4)}(0)&=0.\end{align*}\]

Since the fourth derivative is \(\sin x,\) the pattern repeats. That is, \(f^{(2m)}(0)=0\) and \(f^{(2m+1)}(0)=(−1)^m\) for \(m≥0.\) Thus, we have

\(\begin{align*} p_0(x)&=0,\\[5pt]

p_1(x)&=0+x=x,\\[5pt]

p_2(x)&=0+x+0=x,\\[5pt]

p_3(x)&=0+x+0−\dfrac{1}{3!}x^3=x−\dfrac{x^3}{3!},\\[5pt]

p_4(x)&=0+x+0−\dfrac{1}{3!}x^3+0=x−\dfrac{x^3}{3!},\\[5pt]

p_5(x)&=0+x+0−\dfrac{1}{3!}x^3+0+\dfrac{1}{5!}x^5=x−\dfrac{x^3}{3!}+\dfrac{x^5}{5!},\end{align*}\)

and for \(m≥0\),

\[\begin{align*} p_{2m+1}(x)=p_{2m+2}(x)&=x−\dfrac{x^3}{3!}+\dfrac{x^5}{5!}−⋯+(−1)^m\dfrac{x^{2m+1}}{(2m+1)!}\\[5pt]

&=\sum_{k=0}^m(−1)^k\dfrac{x^{2k+1}}{(2k+1)!}.\end{align*}\]

Graphs of the function and its Maclaurin polynomials are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).

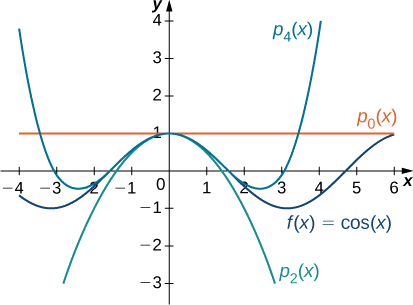

c. For \(f(x)=\cos x\), the values of the function and its first four derivatives at \(x=0\) are given as follows:

\[\begin{align*} f(x)&=\cos x & f(0)&=1\\[5pt]

f′(x)&=−\sin x & f′(0)&=0\\[5pt]

f''(x)&=−\cos x & f''(0)&=−1\\[5pt]

f'''(x)&=\sin x & f'''(0)&=0\\[5pt]

f^{(4)}(x)&=\cos x & f^{(4)}(0)&=1.\end{align*}\]

Since the fourth derivative is \(\sin x\), the pattern repeats. In other words, \(f^{(2m)}(0)=(−1)^m\) and \(f^{(2m+1)}=0\) for \(m≥0\). Therefore,

\(\begin{align*} p_0(x)&=1,\\[5pt]

p_1(x)&=1+0=1,\\[5pt]

p_2(x)&=1+0−\dfrac{1}{2!}x^2=1−\dfrac{x^2}{2!},\\[5pt]

p_3(x)&=1+0−\dfrac{1}{2!}x^2+0=1−\dfrac{x^2}{2!},\\[5pt]

p_4(x)&=1+0−\dfrac{1}{2!}x^2+0+\dfrac{1}{4!}x^4=1−\dfrac{x^2}{2!}+\dfrac{x^4}{4!},\\[5pt]

p_5(x)&=1+0−\dfrac{1}{2!}x^2+0+\dfrac{1}{4!}x^4+0=1−\dfrac{x^2}{2!}+\dfrac{x^4}{4!},\end{align*}\)

and for \(n≥0\),

\[\begin{align*} p_{2m}(x)&=p_{2m+1}(x)\\[5pt]

&=1−\dfrac{x^2}{2!}+\dfrac{x^4}{4!}−⋯+(−1)^m\dfrac{x^{2m}}{(2m)!}\\[5pt]

&=\sum_{k=0}^m(−1)^k\dfrac{x^{2k}}{(2k)!}.\end{align*}\]

Graphs of the function and the Maclaurin polynomials appear in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Find formulas for the Maclaurin polynomials \(p_0,\,p_1,\,p_2\) and \(p_3\) for \(f(x)=\dfrac{1}{1+x}\).

Find a formula for the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Maclaurin polynomial. Write your answer using sigma notation.

- Hint

-

Evaluate the first four derivatives of \(f\) and look for a pattern.

- Answer

-

\(\displaystyle p_0(x)=1,\) \(\displaystyle p_1(x)=1−x,\) \(\displaystyle p_2(x)=1−x+x^2,\) \(\displaystyle p_3(x)=1−x+x^2−x^3,\) \(\displaystyle p_n(x)=1−x+x^2−x^3+⋯+(−1)^nx^n\) \(\displaystyle=\sum_{k=0}^n(−1)^kx^k\)

Taylor’s Theorem with Remainder

Recall that the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomial for a function \(f\) at \(a\) is the \(n^{\text{th}}\) partial sum of the Taylor series for \(f\) at \(a\). Therefore, to determine if the Taylor series converges, we need to determine whether the sequence of Taylor polynomials \({p_n}\) converges. However, not only do we want to know if the sequence of Taylor polynomials converges, we want to know if it converges to \(f\). To answer this question, we define the remainder \(R_n(x)\) as

\[R_n(x)=f(x)−p_n(x). \nonumber \]

For the sequence of Taylor polynomials to converge to \(f\), we need the remainder \(R_n\) to converge to zero. To determine if \(R_n\) converges to zero, we introduce Taylor’s theorem with remainder. Not only is this theorem useful in proving that a Taylor series converges to its related function, but it will also allow us to quantify how well the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomial approximates the function.

Here we look for a bound on \(|R_n|.\) Consider the simplest case: \(n=0\). Let \(p_0\) be the 0th Taylor polynomial at \(a\) for a function \(f\). The remainder \(R_0\) satisfies

\(R_0(x)=f(x)−p_0(x)=f(x)−f(a).\)

If \(f\) is differentiable on an interval \(I\) containing \(a\) and \(x\), then by the Mean Value Theorem there exists a real number \(c\) between \(a\) and \(x\) such that \(f(x)−f(a)=f′(c)(x−a)\). Therefore,

\[R_0(x)=f′(c)(x−a). \nonumber \]

Using the Mean Value Theorem in a similar argument, we can show that if \(f\) is \(n\) times differentiable on an interval \(I\) containing \(a\) and \(x\), then the \(n^{\text{th}}\) remainder \(R_n\) satisfies

\[R_n(x)=\dfrac{f^{(n+1)}(c)}{(n+1)!}(x−a)^{n+1} \nonumber \]

for some real number \(c\) between \(a\) and \(x\). It is important to note that the value \(c\) in the numerator above is not the center \(a\), but rather an unknown value \(c\) between \(a\) and \(x\). This formula allows us to get a bound on the remainder \(R_n\). If we happen to know that \(∣f^{(n+1)}(x)∣\) is bounded by some real number \(M\) on this interval \(I\), then

\[|R_n(x)|≤\dfrac{M}{(n+1)!}|x−a|^{n+1} \nonumber \]

for all \(x\) in the interval \(I\).

We now state Taylor’s theorem, which provides the formal relationship between a function \(f\) and its \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomial \(p_n(x)\). This theorem allows us to bound the error when using a Taylor polynomial to approximate a function value, and will be important in proving that a Taylor series for \(f\) converges to \(f\).

Let \(f\) be a function that can be differentiated \(n+1\) times on an interval \(I\) containing the real number \(a\). Let \(p_n\) be the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomial of \(f\) at \(a\) and let

\[R_n(x)=f(x)−p_n(x) \nonumber \]

be the \(n^{\text{th}}\) remainder. Then for each \(x\) in the interval \(I\), there exists a real number \(c\) between \(a\) and \(x\) such that

\[R_n(x)=\dfrac{f^{(n+1)}(c)}{(n+1)!}(x−a)^{n+1} \nonumber \].

If there exists a real number \(M\) such that \(∣f^{(n+1)}(x)∣≤M\) for all \(x∈I\), then

\[|R_n(x)|≤\dfrac{M}{(n+1)!}|x−a|^{n+1} \nonumber \]

for all \(x\) in \(I\).

Proof

Fix a point \(x∈I\) and introduce the function \(g\) such that

\[g(t)=f(x)−f(t)−f′(t)(x−t)−\dfrac{f''(t)}{2!}(x−t)^2−⋯−\dfrac{f^{(n)}(t)}{n!}(x−t)^n−R_n(x)\dfrac{(x−t)^{n+1}}{(x−a)^{n+1}}. \nonumber \]

We claim that \(g\) satisfies the criteria of Rolle’s theorem. Since \(g\) is a polynomial function (in \(t\)), it is a differentiable function. Also, \(g\) is zero at \(t=a\) and \(t=x\) because

\[ \begin{align*} g(a) &=f(x)−f(a)−f′(a)(x−a)−\dfrac{f''(a)}{2!}(x−a)^2+⋯+\dfrac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}(x−a)^n−R_n(x) \\[4pt] &=f(x)−p_n(x)−R_n(x) \\[4pt] &=0, \\[4pt] g(x) &=f(x)−f(x)−0−⋯−0 \\[4pt] &=0. \end{align*}\]

Therefore, \(g\) satisfies Rolle’s theorem, and consequently, there exists \(c\) between \(a\) and \(x\) such that \(g′(c)=0.\) We now calculate \(g′\). Using the product rule, we note that

\[\dfrac{d}{dt}\left[\dfrac{f^{(n)}(t)}{n!}(x−t)^n\right]=−\dfrac{f^{(n)}(t)}{(n−1)!}(x−t)^{n−1}+\dfrac{f^{(n+1)}(t)}{n!}(x−t)^n. \nonumber \]

Consequently,

\[\begin{align*} g′(t)&=−f′(t)+[f′(t)−f''(t)(x−t)]+\left[f''(t)(x−t)−\dfrac{f'''(t)}{2!}(x−t)^2\right]+⋯ \\

&\quad+\left[\dfrac{f^{(n)}(t)}{(n−1)!}(x−t)^{n−1}−\dfrac{f^{(n+1)}(t)}{n!}(x−t)^n\right]+(n+1)R_n(x)\dfrac{(x−t)^n}{(x−a)^{n+1}}\end{align*} \].

Notice that there is a telescoping effect. Therefore,

\[g'(t)=−\dfrac{f^{(n+1)}(t)}{n!}(x−t)^n+(n+1)R_n(x)\dfrac{(x−t)^n}{(x−a)^{n+1}} \nonumber \].

By Rolle’s theorem, we conclude that there exists a number \(c\) between \(a\) and \(x\) such that \(g′(c)=0.\) Since

\[g′(c)=−\dfrac{f^{(n+1})(c)}{n!}(x−c)^n+(n+1)R_n(x)\dfrac{(x−c)^n}{(x−a)^{n+1}} \nonumber \]

we conclude that

\[−\dfrac{f^{(n+1)}(c)}{n!}(x−c)^n+(n+1)R_n(x)\dfrac{(x−c)^n}{(x−a)^{n+1}}=0. \nonumber \]

Adding the first term on the left-hand side to both sides of the equation and dividing both sides of the equation by \(n+1,\) we conclude that

\[R_n(x)=\dfrac{f^{(n+1)}(c)}{(n+1)!}(x−a)^{n+1} \nonumber \]

as desired. From this fact, it follows that if there exists \(M\) such that \(∣f^{(n+1)}(x)∣≤M\) for all \(x\) in \(I\), then

\[|R_n(x)|≤\dfrac{M}{(n+1)!}|x−a|^{n+1} \nonumber \].

□

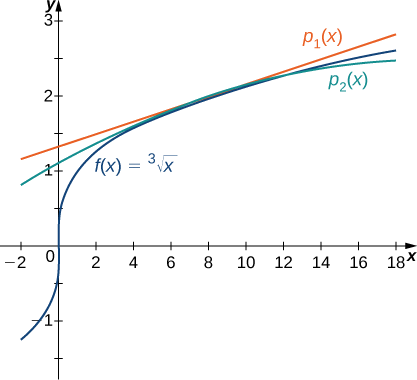

Not only does Taylor’s theorem allow us to prove that a Taylor series converges to a function, but it also allows us to estimate the accuracy of Taylor polynomials in approximating function values. We begin by looking at linear and quadratic approximations of \(f(x)=\sqrt[3]{x}\) at \(x=8\) and determine how accurate these approximations are at estimating \(\sqrt[3]{11}\).

Consider the function \(f(x)=\sqrt[3]{x}\).

- Find the first and second Taylor polynomials for \(f\) at \(x=8\). Use a graphing utility to compare these polynomials with \(f\) near \(x=8.\)

- Use these two polynomials to estimate \(\sqrt[3]{11}\).

- Use Taylor’s theorem to bound the error.

Solution:

a. For \(f(x)=\sqrt[3]{x}\), the values of the function and its first two derivatives at \(x=8\) are as follows:

\[\begin{align*} f(x)&=\sqrt[3]{x}, & f(8)&=2\\[5pt]

f′(x)&=\dfrac{1}{3x^{2/3}}, & f′(8)&=\dfrac{1}{12}\\[5pt]

f''(x)&=\dfrac{−2}{9x^{5/3}}, & f''(8)&=−\dfrac{1}{144.}\end{align*}\]

Thus, the first and second Taylor polynomials at \(x=8\) are given by

\(\begin{align*} p_1(x)&=f(8)+f′(8)(x−8)\\[5pt]

&=2+\dfrac{1}{12}(x−8)\end{align*}\)

\(\begin{align*} p_2(x)&=f(8)+f′(8)(x−8)+\dfrac{f''(8)}{2!}(x−8)^2\\[5pt]

&=2+\dfrac{1}{12}(x−8)−\dfrac{1}{288}(x−8)^2.\end{align*}\)

The function and the Taylor polynomials are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

b. Using the first Taylor polynomial at \(x=8\), we can estimate

\[\sqrt[3]{11}≈p_1(11)=2+\dfrac{1}{12}(11−8)=2.25. \nonumber \]

Using the second Taylor polynomial at \(x=8\), we obtain

\[\sqrt[3]{11}≈p_2(11)=2+\dfrac{1}{12}(11−8)−\dfrac{1}{288}(11−8)^2=2.21875. \nonumber \]

c. By Theorem \(\PageIndex{2}\), there exists a \(c\) in the interval \((8,11)\) such that the remainder when approximating \(\sqrt[3]{11}\) by the first Taylor polynomial satisfies

\[R_1(11)=\dfrac{f''(c)}{2!}(11−8)^2. \nonumber \]

We do not know the exact value of \(c\), so we find an upper bound on \(R_1(11)\) by determining the maximum value of \(f''\) on the interval \((8,11)\). Since \(f''(x)=−\dfrac{2}{9x^{5/3}}\), the largest value for \(|f''(x)|\) on that interval occurs at \(x=8\). Using the fact that \(f''(8)=−\dfrac{1}{144}\), we obtain

\(|R_1(11)|≤\dfrac{1}{144⋅2!}(11−8)^2=0.03125.\)

Similarly, to estimate \(R_2(11)\), we use the fact that

\(R_2(11)=\dfrac{f'''(c)}{3!}(11−8)^3\).

Since \(f'''(x)=\dfrac{10}{27x^{8/3}}\), the maximum value of \(f'''\) on the interval \((8,11)\) is \(f'''(8)≈0.0014468\). Therefore, we have

\(|R_2(11)|≤\dfrac{0.0011468}{3!}(11−8)^3≈0.0065104.\)

Find the first and second Taylor polynomials for \(f(x)=\sqrt{x}\) at \(x=4\). Use these polynomials to estimate \(\sqrt{6}\). Use Taylor’s theorem to bound the error.

- Hint

-

Evaluate \(f(4),f′(4),\) and \(f''(4).\)

- Answer

-

\(p_1(x)=2+\dfrac{1}{4}(x−4);p_2(x)=2+\dfrac{1}{4}(x−4)−\dfrac{1}{64}(x−4)^2;p_1(6)=2.5;p_2(6)=2.4375;\)

\(|R_1(6)|≤0.0625;|R_2(6)|≤0.015625\)

From Example \(\PageIndex{2b}\), the Maclaurin polynomials for \(\sin x\) are given by

\[p_{2m+1}(x)=p_{2m+2}(x)=x−\dfrac{x^3}{3!}+\dfrac{x^5}{5!}−\dfrac{x^7}{7!}+⋯+(−1)^m\dfrac{x^{2m+1}}{(2m+1)!} \nonumber \]

for \(m=0,1,2,….\)

- Use the fifth Maclaurin polynomial for \(\sin x\) to approximate \(\sin\left(\dfrac{π}{18}\right)\) and bound the error.

- For what values of \(x\) does the fifth Maclaurin polynomial approximate \(\sin x\) to within \(0.0001\)?

Solution

a.

The fifth Maclaurin polynomial is

\[p_5(x)=x−\dfrac{x^3}{3!}+\dfrac{x^5}{5!} \nonumber \].

Using this polynomial, we can estimate as follows:

\[\sin\left(\dfrac{π}{18}\right)≈p_5\left(\dfrac{π}{18}\right)=\dfrac{π}{18}−\dfrac{1}{3!}\left(\dfrac{π}{18}\right)^3+\dfrac{1}{5!}\left(\dfrac{π}{18}\right)^5≈0.173648. \nonumber \]

To estimate the error, use the fact that the sixth Maclaurin polynomial is \(p_6(x)=p_5(x)\) and calculate a bound on \(R_6(\dfrac{π}{18})\). By Theorem \(\PageIndex{2}\), the remainder is

\[R_6\left(\dfrac{π}{18}\right)=\dfrac{f^{(7)}(c)}{7!}\left(\dfrac{π}{18}\right)^7 \nonumber \]

for some \(c\) between 0 and \(\dfrac{π}{18}\). Using the fact that \(∣f^{(7)}(x)∣≤1\) for all \(x\), we find that the magnitude of the error is at most

\[\dfrac{1}{7!}⋅\left(\dfrac{π}{18}\right)^7≤9.8×10^{−10}. \nonumber \]

b.

We need to find the values of \(x\) such that

\[\dfrac{1}{7!}|x|^7≤0.0001. \nonumber \]

Solving this inequality for \(x\), we have that the fifth Maclaurin polynomial gives an estimate to within \(0.0001\) as long as \(|x|<0.907.\)

Use the fourth Maclaurin polynomial for \(\cos x\) to approximate \(\cos\left(\dfrac{π}{12}\right).\)

- Hint

-

The fourth Maclaurin polynomial is \(p_4(x)=1−\dfrac{x^2}{2!}+\dfrac{x^4}{4!}\).

- Answer

-

\(0.96593\)

Now that we are able to bound the remainder \(R_n(x)\), we can use this bound to prove that a Taylor series for \(f\) at a converges to \(f\).

Representing Functions with Taylor and Maclaurin Series

We now discuss issues of convergence for Taylor series. We begin by showing how to find a Taylor series for a function, and how to find its interval of convergence.

Find the Taylor series for \(f(x)=\dfrac{1}{x}\) at \(x=1\). Determine the interval of convergence.

Solution

For \(f(x)=\dfrac{1}{x},\) the values of the function and its first four derivatives at \(x=1\) are

\[\begin{align*} f(x)&=\dfrac{1}{x} & f(1)&=1\\[5pt]

f′(x)&=−\dfrac{1}{x^2} & f′(1)&=−1\\[5pt]

f''(x)&=\dfrac{2}{x^3} & f''(1)&=2!\\[5pt]

f'''(x)&=−\dfrac{3⋅2}{x^4} & f'''(1)&=−3!\\[5pt]

f^{(4)}(x)&=\dfrac{4⋅3⋅2}{x^5} & f^{(4)}(1)&=4!.\end{align*}\]

That is, we have \(f^{(n)}(1)=(−1)^nn!\) for all \(n≥0\). Therefore, the Taylor series for \(f\) at \(x=1\) is given by

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^∞\dfrac{f^{(n)}(1)}{n!}(x−1)^n=\sum_{n=0}^∞(−1)^n(x−1)^n\).

To find the interval of convergence, we use the ratio test. We find that

\(\dfrac{|a_{n+1}|}{|a_n|}=\dfrac{∣(−1)^{n+1}(x−1)n^{+1}∣}{|(−1)^n(x−1)^n|}=|x−1|\).

Thus, the series converges if \(|x−1|<1.\) That is, the series converges for \(0<x<2\). Next, we need to check the endpoints. At \(x=2\), we see that

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^∞(−1)^n(2−1)^n=\sum_{n=0}^∞(−1)^n\)

diverges by the divergence test. Similarly, at \(x=0,\)

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^∞(−1)^n(0−1)^n=\sum_{n=0}^∞(−1)^{2n}=\sum_{n=0}^∞1\)

diverges. Therefore, the interval of convergence is \((0,2)\).

Find the Taylor series for \(f(x)=\dfrac{1}{2x}\) at \(x=2\) and determine its interval of convergence.

- Hint

-

\(f^{(n)}(2)=\dfrac{(−1)^nn!}{2^{n+2}}\)

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{1}{4}\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^∞\left(\dfrac{2−x}{2}\right)^n\). The interval of convergence is \((0,4)\).

We know that the Taylor series found in this example converges on the interval \((0,2)\), but how do we know it actually converges to \(f\)? We consider this question in more generality in a moment, but for this example, we can answer this question by writing

\[ f(x)=\dfrac{1}{x}=\dfrac{1}{1−(1−x)}. \nonumber \]

That is, \(f\) can be represented by the geometric series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^∞(1−x)^n\). Since this is a geometric series, it converges to \(\dfrac{1}{x}\) as long as \(|1−x|<1.\) Therefore, the Taylor series found in Example \(\PageIndex{5}\) does converge to \(f(x)=\dfrac{1}{x}\) on \((0,2).\)

We now consider the more general question: if a Taylor series for a function \(f\) converges on some interval, how can we determine if it actually converges to \(f\)? To answer this question, recall that a series converges to a particular value if and only if its sequence of partial sums converges to that value. Given a Taylor series for \(f\) at \(a\), the \(n^{\text{th}}\) partial sum is given by the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomial \(p_n\). Therefore, to determine if the Taylor series converges to \(f\), we need to determine whether

\(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}p_n(x)=f(x)\).

Since the remainder \(R_n(x)=f(x)−p_n(x)\), the Taylor series converges to \(f\) if and only if

\(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}R_n(x)=0.\)

We now state this theorem formally.

Suppose that \(f\) has derivatives of all orders on an interval \(I\) containing \(a\). Then the Taylor series

\[\sum_{n=0}^∞\dfrac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}(x−a)^n \nonumber \]

converges to \(f(x)\) for all \(x\) in \(I\) if and only if

\[\lim_{n→∞}R_n(x)=0 \nonumber \]

for all \(x\) in \(I\).

With this theorem, we can prove that a Taylor series for \(f\) at \(a\) converges to \(f\) if we can prove that the remainder \(R_n(x)→0\). To prove that \(R_n(x)→0\), we typically use the bound

\[|R_n(x)|≤\dfrac{M}{(n+1)!}|x−a|^{n+1} \nonumber \]

from Taylor’s theorem with remainder.

In the next example, we find the Maclaurin series for \(e^x\) and \(\sin x\) and show that these series converge to the corresponding functions for all real numbers by proving that the remainders \(R_n(x)→0\) for all real numbers \(x\).

For each of the following functions, find the Maclaurin series and its interval of convergence. Use Theorem \(\PageIndex{2}\) to prove that the Maclaurin series for \(f\) converges to \(f\) on that interval.

- \(e^x\)

- \(\sin x\)

Solution

a. Using the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Maclaurin polynomial for \(e^x\) found in Example \(\PageIndex{2a}\), we find that the Maclaurin series for \(e^x\) is given by

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^∞\dfrac{x^n}{n!}\).

To determine the interval of convergence, we use the ratio test. Since

\(\dfrac{|a_{n+1}|}{|a_n|}=\dfrac{|x|^{n+1}}{(n+1)!}⋅\dfrac{n!}{|x|^n}=\dfrac{|x|}{n+1}\),

we have

\(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}\dfrac{|a_{n+1}|}{|a_n|}=\lim_{n→∞}\dfrac{|x|}{n+1}=0\)

for all \(x\). Therefore, the series converges absolutely for all \(x\), and thus, the interval of convergence is \((−∞,∞)\). To show that the series converges to \(e^x\) for all \(x\), we use the fact that \(f^{(n)}(x)=e^x\) for all \(n≥0\) and \(e^x\) is an increasing function on \((−∞,∞)\). Therefore, for any real number \(b\), the maximum value of \(e^x\) for all \(|x|≤b\) is \(e^b\). Thus,

\(|R_n(x)|≤\dfrac{e^b}{(n+1)!}|x|^{n+1}\).

Since we just showed that

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^∞\dfrac{|x|^n}{n!}\)

converges for all \(x\), by the divergence test, we know that

\(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}\dfrac{|x|^{n+1}}{(n+1)!}=0\)

for any real number \(x\). By combining this fact with the squeeze theorem, the result is \(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}R_n(x)=0.\)

b. Using the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Maclaurin polynomial for \(\sin x\) found in Example \(\PageIndex{2b}\), we find that the Maclaurin series for \(\sin x\) is given by

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^∞(−1)^n\dfrac{x^{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!}\).

In order to apply the ratio test, consider

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{|a_{n+1}|}{|a_n|}&=\dfrac{|x|^{2n+3}}{(2n+3)!}⋅\dfrac{(2n+1)!}{|x|^{2n+1}}\\[5pt]

&=\dfrac{|x|^2}{(2n+3)(2n+2)}\end{align*}. \nonumber \]

Since

\(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}\dfrac{|x|^2}{(2n+3)(2n+2)}=0\)

for all \(x\), we obtain the interval of convergence as \((−∞,∞).\) To show that the Maclaurin series converges to \(\sin x\), look at \(R_n(x)\). For each \(x\) there exists a real number \(c\) between \(0\) and \(x\) such that

\(R_n(x)=\dfrac{f^{(n+1)}(c)}{(n+1)!}x^{n+1}\).

Since \(∣f^{(n+1)}(c)∣≤1\) for all integers \(n\) and all real numbers \(c\), we have

\(|R_n(x)|≤\dfrac{|x|^{n+1}}{(n+1)!}\)

for all real numbers \(x\). Using the same idea as in part a., the result is \(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}R_n(x)=0\) for all \(x\), and therefore, the Maclaurin series for \(\sin x\) converges to \(\sin x\) for all real \(x\).

Find the Maclaurin series for \(f(x)=\cos x\). Use the ratio test to show that the interval of convergence is \((−∞,∞)\). Show that the Maclaurin series converges to \(\cos x\) for all real numbers \(x\).

- Hint

-

Use the Maclaurin polynomials for \(\cos x.\)

- Answer

-

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^∞\dfrac{(−1)^nx^{2n}}{(2n)!}\)

By the ratio test, the interval of convergence is \((−∞,∞).\) Since \(|R_n(x)|≤\dfrac{|x|^{n+1}}{(n+1)!}\), the series converges to \(\cos x\) for all real \(x\).

In this project, we use the Maclaurin polynomials for \(e^x\) to prove that \(e\) is irrational. The proof relies on supposing that \(e\) is rational and arriving at a contradiction. Therefore, in the following steps, we suppose \(e=r/s\) for some integers \(r\) and \(s\) where \(s≠0.\)

- Write the Maclaurin polynomials \(p_0(x),p_1(x),p_2(x),p_3(x),p_4(x)\) for \(e^x\). Evaluate \(p_0(1),p_1(1),p_2(1),p_3(1),p_4(1)\) to estimate \(e\).

- Let \(R_n(x)\) denote the remainder when using \(p_n(x)\) to estimate \(e^x\). Therefore, \(R_n(x)=e^x−p_n(x)\), and \(R_n(1)=e−p_n(1)\). Assuming that \(e=\dfrac{r}{s}\) for integers \(r\) and \(s\), evaluate \(R_0(1),R_1(1),R_2(1),R_3(1),R_4(1).\)

- Using the results from part 2, show that for each remainder \(R_0(1),R_1(1),R_2(1),R_3(1),R_4(1),\) we can find an integer \(k\) such that \(kR_n(1)\) is an integer for \(n=0,1,2,3,4.\)

- Write down the formula for the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Maclaurin polynomial \(p_n(x)\) for \(e^x\) and the corresponding remainder \(R_n(x).\) Show that \(sn!R_n(1)\) is an integer.

- Use Taylor’s theorem to write down an explicit formula for \(R_n(1)\). Conclude that \(R_n(1)≠0\), and therefore, \(sn!R_n(1)≠0\).

- Use Taylor’s theorem to find an estimate on \(R_n(1)\). Use this estimate combined with the result from part 5 to show that \(|sn!R_n(1)|<\dfrac{se}{n+1}\). Conclude that if \(n\) is large enough, then \(|sn!R_n(1)|<1\). Therefore, \(sn!R_n(1)\) is an integer with magnitude less than 1. Thus, \(sn!R_n(1)=0\). But from part 5, we know that \(sn!R_n(1)≠0\). We have arrived at a contradiction, and consequently, the original supposition that e is rational must be false.

Key Concepts

- Taylor polynomials are used to approximate functions near a value \(x=a\). Maclaurin polynomials are Taylor polynomials at \(x=0\).

- The \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomials for a function \(f\) are the partial sums of the Taylor series for \(f\).

- If a function \(f\) has a power series representation at \(x=a\), then it is given by its Taylor series at \(x=a\).

- A Taylor series for \(f\) converges to \(f\) if and only if \(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}R_n(x)=0\) where \(R_n(x)=f(x)−p_n(x)\).

- The Taylor series for \(e^x, \sin x\), and \(\cos x\) converge to the respective functions for all real x.

Key Equations

- Taylor series for the function \(f\) at the point \(x=a\)

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^∞\dfrac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}(x−a)^n=f(a)+f′(a)(x−a)+\dfrac{f''(a)}{2!}(x−a)^2+⋯+\dfrac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}(x−a)^n+⋯\)

Glossary

- Maclaurin polynomial

- a Taylor polynomial centered at \(0\); the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomial for \(f\) at \(0\) is the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Maclaurin polynomial for \(f\)

- Maclaurin series

- a Taylor series for a function \(f\) at \(x=0\) is known as a Maclaurin series for \(f\)

- Taylor polynomials

- the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomial for \(f\) at \(x=a\) is \(p_n(x)=f(a)+f′(a)(x−a)+\dfrac{f''(a)}{2!}(x−a)^2+⋯+\dfrac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}(x−a)^n\)

- Taylor series

- a power series at \(a\) that converges to a function \(f\) on some open interval containing \(a\).

- Taylor’s theorem with remainder

-

for a function \(f\) and the \(n^{\text{th}}\)-degree Taylor polynomial for \(f\) at \(x=a\), the remainder \(R_n(x)=f(x)−p_n(x)\) satisfies \(R_n(x)=\dfrac{f^{(n+1)}(c)}{(n+1)!}(x−a)^{n+1}\)

for some\(c\) between \(x\) and \(a\); if there exists an interval \(I\) containing \(a\) and a real number \(M\) such that \(∣f^{(n+1)}(x)∣≤M\) for all \(x\) in \(I\), then \(|R_n(x)|≤\dfrac{M}{(n+1)!}|x−a|^{n+1}\)