2.5: Circumscribed and Inscribed Circles

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Recall from the Law of Sines that any triangle △ABC has a common ratio of sides to sines of opposite angles, namely

asinA = bsinB = csinC .

This common ratio has a geometric meaning: it is the diameter (i.e. twice the radius) of the unique circle in which △ABC can be inscribed, called the circumscribed circle of the triangle. Before proving this, we need to review some elementary geometry.

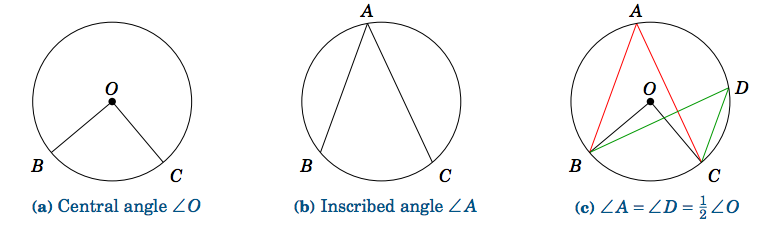

An inscribed angle of a circle is an angle whose vertex is a point A on the circle and whose sides are line segments (called chords) from A to two other points on the circle. In Figure 2.5.1(b), ∠A is an inscribed angle that intercepts the arc ⏜BC. We state here without proof a useful relation between inscribed and central angles:

If an inscribed angle ∠A and a central angle ∠O intercept the same arc, then ∠A=12∠O. Thus, inscribed angles which intercept the same arc are equal.

Figure 2.5.1(c) shows two inscribed angles, ∠A and ∠D, which intercept the same arc ⏜BC as the central angle ∠O, and hence ∠A=∠D=12∠O (so ∠O=2∠A=2∠D).

We will now prove our assertion about the common ratio in the Law of Sines:

For any triangle △ABC, the radius R of its circumscribed circle is given by:

2R = asinA = bsinB = csinC

Note: For a circle of diameter 1, this means a=sinA, b=sinB, and c=sinC.)

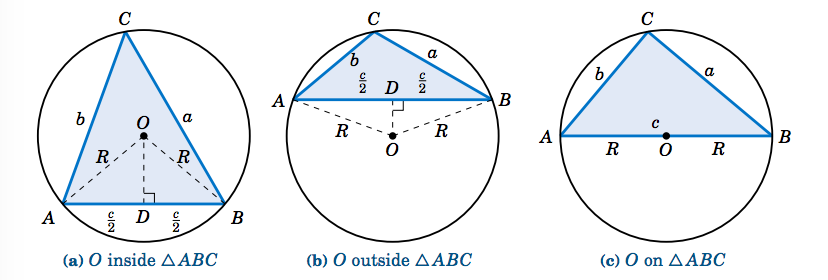

To prove this, let O be the center of the circumscribed circle for a triangle △ABC. Then O can be either inside, outside, or on the triangle, as in Figure 2.5.2 below. In the first two cases, draw a perpendicular line segment from O to ¯AB at the point D.

The radii ¯OA and ¯OB have the same length R, so △AOB is an isosceles triangle. Thus, from elementary geometry we know that ¯OD bisects both the angle ∠AOB and the side ¯AB. So ∠AOD=12∠AOB and AD=c2. But since the inscribed angle ∠ACB and the central angle ∠AOB intercept the same arc ⏜AB, we know from Theorem 2.4 that ∠ACB=12∠AOB. Hence, ∠ACB=∠AOD. So since C=∠ACB, we have

sinC = sin∠AOD = ADOA = c2R = c2R⇒2R = csinC ,

so by the Law of Sines the result follows if O is inside or outside △ABC.

Now suppose that O is on △ABC, say, on the side ¯AB, as in Figure 2.5.2(c). Then ¯AB is a diameter of the circle, so C=90∘ by Thales' Theorem. Hence, sinC=1, and so 2R=AB=c=c1=csinC, and the result again follows by the Law of Sines. QED

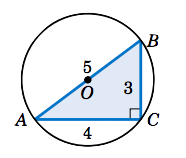

Solution:

We know that △ABC is a right triangle. So as we see from Figure 2.5.3, sinA=3/5. Thus,

2R = asinA = 335 = 5⇒R = 2.5 .

Note that since R=2.5, the diameter of the circle is 5, which is the same as AB. Thus, ¯AB must be a diameter of the circle, and so the center O of the circle is the midpoint of ¯AB.

For any right triangle, the hypotenuse is a diameter of the circumscribed circle, i.e. the center of the circle is the midpoint of the hypotenuse.

For the right triangle in the above example, the circumscribed circle is simple to draw; its center can be found by measuring a distance of 2.5 units from A along ¯AB.

We need a different procedure for acute and obtuse triangles, since for an acute triangle the center of the circumscribed circle will be inside the triangle, and it will be outside for an obtuse triangle. Notice from the proof of Theorem 2.5 that the center O was on the perpendicular bisector of one of the sides (¯AB). Similar arguments for the other sides would show that O is on the perpendicular bisectors for those sides:

For any triangle, the center of its circumscribed circle is the intersection of the perpendicular bisectors of the sides.

Find the radius R of the circumscribed circle for the triangle △ABC from Example 2.6 in Section 2.2: a=2, b=3, and c=4. Then draw the triangle and the circle.

Solution:

In Example 2.6 we found A=28.9∘, so 2R=asinA=2sin28.9∘=4.14, so R=2.07.

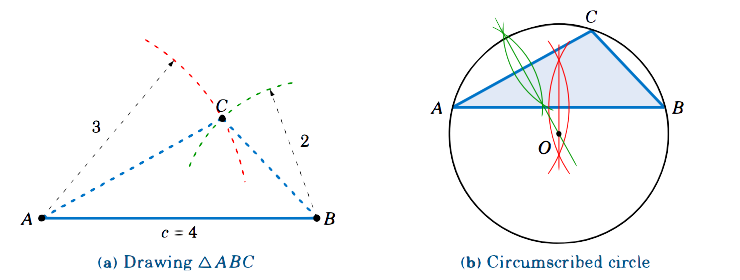

In Figure 2.5.5(a) we show how to draw △ABC: use a ruler to draw the longest side ¯AB of length c=4, then use a compass to draw arcs of radius 3 and 2 centered at A and B, respectively. The intersection of the arcs is the vertex C.

In Figure 2.5.5(b) we show how to draw the circumscribed circle: draw the perpendicular bisectors of ¯AB and ¯AC; their intersection is the center O of the circle. Use a compass to draw the circle centered at O which passes through A.

Theorem 2.5 can be used to derive another formula for the area of a triangle:

For a triangle △ABC, let K be its area and let R be the radius of its circumscribed circle. Then

K = abc4R(and hence R = abc4K ) .

To prove this, note that by Theorem 2.5 we have

2R = asinA = bsinB = csinC⇒sinA = a2R , sinB = b2R , sinC = c2R .

Substitute those expressions into Equation 2.26 from Section 2.4 for the area K:

K = a2sinBsinC2sinA = a2⋅b2R⋅c2R2⋅a2R = abc4RQED

Combining Theorem 2.8 with Heron's formula for the area of a triangle, we get:

For a triangle △ABC, let s=12(a+b+c). Then the radius R of its circumscribed circle is

R = abc4√s(s−a)(s−b)(s−c) .

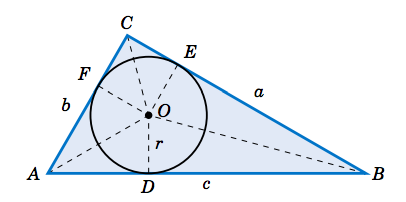

Let r be the radius of the inscribed circle, and let D, E, and F be the points on ¯AB, ¯BC, and ¯AC, respectively, at which the circle is tangent. Then ¯OD⊥¯AB, ¯OE⊥¯BC, and ¯OF⊥¯AC. Thus, △OAD and △OAF are equivalent triangles, since they are right triangles with the same hypotenuse ¯OA and with corresponding legs ¯OD and ¯OF of the same length r. Hence, ∠OAD=∠OAF, which means that ¯OA bisects the angle A. Similarly, ¯OB bisects B and ¯OC bisects C. We have thus shown:

For any triangle, the center of its inscribed circle is the intersection of the bisectors of the angles.

We will use Figure 2.5.6 to find the radius r of the inscribed circle. Since ¯OA bisects A, we see that tan12A=rAD, and so r=AD⋅tan12A. Now, △OAD and △OAF are equivalent triangles, so AD=AF. Similarly, DB=EB and FC=CE. Thus, if we let s=12(a+b+c), we see that

2s = a + b + c = (AD+DB) + (CE+EB) + (AF+FC)= AD + EB + CE + EB + AD + CE = 2(AD+EB+CE)s = AD + EB + CE = AD + aAD = s−a .

Hence, r=(s−a)tan12A. Similar arguments for the angles B and C give us:

For any triangle △ABC, let s=12(a+b+c). Then the radius r of its inscribed circle is

r = (s−a)tan12A = (s−b)tan12B = (s−c)tan12C .

We also see from Figure 2.5.6 that the area of the triangle △AOB is

Area(△AOB) = 12base×height = 12cr .

Similarly, Area(△BOC)=12ar and Area(△AOC)=12br. Thus, the area K of △ABC is

K = Area(△AOB) + Area(△BOC) + Area(△AOC) = 12cr + 12ar + 12br= 12(a+b+c)r = sr , so by Heron's formula we getr = Ks = √s(s−a)(s−b)(s−c)s = √s(s−a)(s−b)(s−c)s2 = √(s−a)(s−b)(s−c)s .

We have thus proved the following theorem:

For any triangle △ABC, let s=12(a+b+c). Then the radius r of its inscribed circle is

r = Ks = √(s−a)(s−b)(s−c)s .

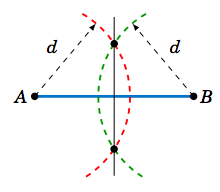

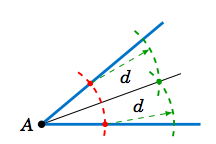

Recall from geometry how to bisect an angle: use a compass centered at the vertex to draw an arc that intersects the sides of the angle at two points. At those two points use a compass to draw an arc with the same radius, large enough so that the two arcs intersect at a point, as in Figure 2.5.7. The line through that point and the vertex is the bisector of the angle. For the inscribed circle of a triangle, you need only two angle bisectors; their intersection will be the center of the circle.

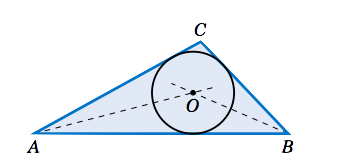

Find the radius r of the inscribed circle for the triangle △ABC from Example 2.6 in Section 2.2: a=2, b=3, and c=4. Draw the circle.

Solution:

Using Theorem 2.11 with s=12(a+b+c)=12(2+3+4)=92, we have

r = √(s−a)(s−b)(s−c)s = √(92−2)(92−3)(92−4)92 = √512 .

Figure 2.5.8 shows how to draw the inscribed circle: draw the bisectors of A and B, then at their intersection use a compass to draw a circle of radius r=√5/12≈0.645.