7.1: One-to-One Functions

- Page ID

- 212063

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)You’ve seen that some equations have only one solution (for example, \(5 - 2x = 3\) and \(x^3 = 8\)), while some have two solutions (\(x^2 + 3 = 7\)) and some even have an infinite number of solutions (\(\sin(x) = 0.8\)). The graphs of \(y = 5 - 2x\), \(y = x^3\), \(y = x^2 + 3\) and \(y = \sin(x)\) and the solutions of the equations mentioned above appear below:

Functions \(f\) for which equations of the form \(f(x) = k\) have at most one solution for each value of \(k\) (that is, each outcome \(k\) comes from only one input \(x\)) arise often in applications and possess a number of useful mathematical properties. This brief section focuses on those functions and examines some of their properties.

- \(f(x) = 0\) for \(f(x) = x(x - 4)\)

- \(g(x) = 3\) for \(g\) given in the table below:

\(x\) 0 1 2 3 4 5 \(g(x)\) 5 7 3 5 0 7 - \(h(x) = 4\) for \(h\) given by the graph below:

- \(f(x) = k\) for \(f(x) = e^x\).

Solution

- Two: \(x(4 - x) = 0 \Rightarrow x = 0\) or \(x = 4\).

- One: \(g(x) = 3\) only if \(x = 2\).

- Two: \(h(x) = 4\) if \(x \approx 1.2\) or if \(x \approx 4\).

- If \(k > 0\), it has one solution: \(x = \ln(k)\). If \(k \leq 0\), it has no solutions.

How many solutions does each equation have?

- \(f(x) = 4\) for \(f(x) = x(4 - x)\)

- \(g(x) = 7\) for \(g\) given by the table from Example \(\PageIndex{1}\).

- \(H(x) = 3\) for \(H\) given by the graph below:

- \(f(x) = 5\) for \(f(x) = \ln(x)\)

- Answer

-

- One: solve \(x(4 - x) = 4\) to get \(x = 2\).

- Two: \(x = 1\) and \(x = 5\).

- One: \(x \approx 3.5\).

- One: solve \(5 = \ln(x)\) to get \(x = e^5 \approx 148.4\).

Horizontal Line Test

You should be familiar with the Vertical Line Test, a graphical tool you can use to help determine whether or not a curve in the \(xy\)-plane is the graph of a function. (If not, review Section 0.3.) A similar geometrical test leads to the definition of a one-to-one function and provides a tool for helping to determine when a function is one-to-one.

A function is one-to-one if each horizontal line intersects the graph of the function at most once.

Equivalently, a function \(y = f(x)\) is one-to-one if two distinct \(x\)-values always produce two distinct \(y\)-values: that is, \(a \neq b \Rightarrow f(a) \neq f(b)\). This immediately tells us that every strictly increasing function is one-to-one, and that every strictly decreasing function is one-to-one. (Why?)

For any function, if we know an input value we can calculate the output, but an output may arise from any of several different inputs. With a one-to-one function, each output comes from only one input.

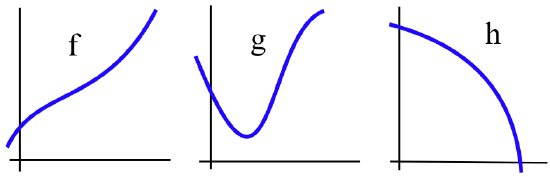

- Which functions in the figure below are one-to-one?

- Which functions in the table below are one-to-one?

\(x\) \(f(x)\) \(g(x)\) \(h(x)\) 0 5 7 2 1 2 3 -1 2 3 0 5 3 5 1 4 4 0 6 3 5 1 3 0

Solution

- In the figure, \(f\) and \(h\) are one-to-one; \(g\) fails the Horizontal Line Test, so \(g\) is not one-to-one.

- In the table, \(h\) is one-to-one, while \(f\) and \(g\) are not one-to-one because \(f(0) = f(3)\) and \(g(1) = g(5)\).

- Which functions graphed below are one-to-one?

- Which functions in the table below are one-to-one?

\(x\) \(f(x)\) \(g(x)\) \(h(x)\) 0 4 2 -2 1 2 3 5 2 -2 0 1 3 5 4 14 4 3 6 3 5 1 7 1

- Answer

-

- Only \(g\) is one-to-one; \(f\) and \(h\) fail the Horizontal Line Test.

- Both \(f\) and \(g\) are one-to-one; \(h\) is not, because \(h(2)=h(5)\).

Let \(f(x) = 2x + 1\):

Find the values of \(x\) so that:

- \(f(x) = 9\) and

- \(f(x) = a\) and then

- solve \(f(y) = x\) for \(y\).

Solution

- \(9 = f(x) = 2x + 1 \Rightarrow 8 = 2x \Rightarrow x = \frac82 = 4\)

- \(a = 2x + 1\) \(\Rightarrow 2x = a - 1 \Rightarrow x = \frac{a - 1}{2}\)

- \(\displaystyle x = f(y) = 2y + 1 \Rightarrow 2y = x - 1\) so \(\displaystyle y = \frac{x - 1}{2}\). Notice that this new function reverses the operations of \(f(x)\), applied in reverse order: \(f(x)\) multiplies \(x\) by \(2\), then adds \(1\); the new function subtracts \(1\), then divides by \(2\).

Let \(g(x) = 3x - 5\). Find the values of \(x\) so that:

- \(g(x) = 7\) and

- \(g(x) = b\) and then

- solve \(g(y) = x\) for \(y\).

- Answer

-

- \(3x - 5 = 7 \Rightarrow 3x=12 \Rightarrow x = 4\)

- \(\displaystyle 3x - 5 = a \Rightarrow 3x = a + 5 \Rightarrow x = \frac{a+5}{3}\)

- \(\displaystyle f(x) = 3x - 5 \Rightarrow f(y) = 3y-5\) so \(\displaystyle f(y) = x \Rightarrow 3y-5 = x \Rightarrow 3y=x+5 \Rightarrow y = \frac{x+5}{3}\)

Show that exponential growth, for example \(f(x) = e^{3x}\), and exponential decay, for example \(g(x) = e^{-2x}\), are both one-to-one.

- Answer

-

If \(f(x) = e^{kx}\) where \(k>0\) then \(f'(x) = k\cdot e^{kx} > 0\) so \(f(x)\) is strictly increasing, hence one-to-one. If \(g(x) = e^{rx}\) where \(r<0\) then \(g'(x) = r\cdot e^{rx} < 0\) so \(g(x)\) is strictly decreasing, hence one-to-one.

Problems

In Problems 1–4, explain why each given function is (or is not) one-to-one.

- \(f(x) = 3x - 5\), \(y = 3 - x\), \(g(x)\) given by the table below:

and \(h(x)\) given by the graph below:\(x\) \(g(x)\) 0 3 1 4 2 5 3 2 4 4

- \(\displaystyle f(x) = \frac{x}{4}\), \(y = x^2 + 3\), \(g(x)\) given by the table below:

and \(h(x)\) given by the graph below:\(x\) \(g(x)\) 0 3 1 2 2 0 3 -2 4 1

- \(\displaystyle f(x) = \sin(x)\), \(y = e^x - 2\), \(g(x)\) given by the table below:

and \(h(x)\) given by the graph below:\(x\) \(g(x)\) 0 -1 1 5 2 3 3 1 4 0

- \(\displaystyle f(x) = 17\), \(y = x^3-1\), \(g(x)\) given by the table below:

and \(h(x)\) given by the graph below:\(x\) \(g(x)\) 0 2 1 5 2 4 3 1 4 2

- Is the relation between people and Social Security numbers a function? A one-to-one function?

- Is the relation between people and phone numbers a function? If so, is it one-to-one?

- What would it mean if the scores on a calculus test were one-to-one?

- The relation given below represents “\(y\) is married to \(x\)”:

\(x\) A B C D \(y\) P Q P R - Is this relation a function?

- Is it one-to-one?

- Is P breaking the law?

- Is A breaking the law?

- In how many places can a one-to-one function touch the \(x\)-axis?

- Can a continuous one-to-one function have the values given below? Explain.

\(x\) 1 3 5 \(f(x)\) 2 7 3 - The graph of \(f(x) = x - 2\cdot\lfloor x \rfloor\) for \(-2 \leq x \leq 3\) appears below:

- Is \(f\) a one-to-one function?

- Is \(f\) an increasing function?

- Is \(f\) a decreasing function?

- Is every linear function \(L(x) = ax + b\) one-to-one? If not, which linear functions are one-to-one?

- Show that \(f(x) = \ln(x)\) is one-to-one for \(x > 0\).

- Show that \(g(x) = e^x\) is one-to-one.

- The table below gives an encoding rule for a six-letter alphabet:

a b c d e f d c f e b a - Is the encoding rule a function?

- Is the encoding rule one-to-one?

- Encode the word “bad.”

- Create a table for decoding the encoded letters and use it to decode your answer to part (c).

- A graph of the encoding rule appears below:

Create a graph of the decoding rule. - Compare the encoding and decoding graphs.

- The table below gives an encoding rule for a six-letter alphabet:

a b c d e f b d b b a c - Is the encoding rule a function?

- Is the encoding rule one-to-one?

- Encode the word “bad.”

- Create a table for decoding the encoded letters and use it to decode your answer to part (c).

- Create a graph of the encoding rule.

- Create a graph of the decoding rule.

- Compare the encoding and decoding graphs.

- The table below gives an encoding rule for a six-letter alphabet:

a b c d e f d f e a c b - Is the encoding rule a function?

- Is the encoding rule one-to-one?

- Encode the word “bad.”

- Create a table for decoding the encoded letters and use it to decode your answer to part (c).

- Create a graph of the encoding rule.

- Create a graph of the decoding rule.

- Compare the encoding and decoding graphs.

- What happens if you encode a word, then encode the encoded word? For example, \(\mbox{encode}\left(\mbox{encode}\left(\mbox{“bad”}\right)\right) = \mbox{?}\)

- The table below gives an encoding rule for a six-letter alphabet:

a b c d e f e a f c b d - Is the encoding rule a function?

- Is the encoding rule one-to-one?

- Encode the word “bad.”

- Create a table for decoding the encoded letters and use it to decode your answer to part (c).

- Create a graph of the encoding rule.

- Create a graph of the decoding rule.

- Compare the encoding and decoding graphs.

- What happens if you apply this encoding rule three times in succession? For example: \(\mbox{encode}\left(\mbox{encode}\left(\mbox{encode}\left(\mbox{“bad”}\right)\right)\right) = \mbox{?}\)