7.3: Inverse Trigonometric Functions

- Page ID

- 212065

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)We now turn our attention to the inverse trigonometric functions, their properties and their graphs, focusing on properties and techniques needed to investigate derivatives and integrals of these functions. We will concentrate on the inverse sine and inverse tangent functions, the two inverse trigonometric functions that arise most often in calculus.

Inverse Sine: Solving \(k = \sin(x)\) for \(x\)

It is straightforward to solve the equation \(3 = e^x\):

Simply apply the natural logarithm function, the inverse of the exponential function \(e^x\), to each side of the equation to get \(\ln( 3 ) = \ln\left(e^x\right) = x\). Because the function \(f(x) = e^x\) is one-to-one, the equation \(3 = e^x\) has only the one solution \(x = \ln(3) \approx 1.1\).

The solution of the equation \(0.5 = \sin(x)\) presents more difficulties. As the figure below illustrates:

the function \(f(x) = \sin(x)\) is not one-to-one: its graph reflected about the line \(y=x\):

is not the graph of a function. Sometimes, however, it is necessary to “undo” the sine function, and we can do so by restricting its domain to the interval \(\left[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right]\). For \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq x \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\), the function \(f(x) = \sin(x)\) is one-to-one and has an inverse function — and the graph of the inverse function

is the reflection about the line \(y = x\) of the (restricted) graph of \(y = \sin(x)\).

Many textbooks — and most calculators — use the notation \(\sin^{-1}(x)\) for \(\arcsin(x)\). You must be very careful to never interpret \(\sin^{-1}(x)\) to mean:\[\left(\sin(x)\right)^{-1} = \frac{1}{\sin(x)} =\csc(x)\]We avoid the \(\sin^{-1}(x)\) notation for this reason and suggest that you do as well.

We call this inverse of the (restricted) sine function the arcsine and denote it \(\arcsin(x)\). The name “arcsine” comes from the unit-circle definition of the sine function. On the unit circle:

if \(\theta\) is the length of the arc whose sine is \(x\), then \(\sin(\theta) = x\) and \(\theta = \arcsin(x)\). Using the right-triangle definition of sine:

\(\theta\) represents an angle whose sine is \(x\).

For \(-1 \leq x \leq 1\) and \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq y \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\):\[y = \arcsin(x) \iff x = \sin(y)\]The domain of \(\arcsin(x)\) is \(\left[-1, 1\right]\) and its range is \(\left[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right]\).

The (restricted) sine function and the arcsine are inverses of each other:

\begin{align*}

-1 \leq x \leq 1 \ &\Rightarrow \ \sin\left(\arcsin(x)\right) = x\\

-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq y \leq \frac{\pi}{2} \ &\Rightarrow \ \arcsin\left(\sin(y)\right) = y\end{align*}

Right Triangles and Arcsine

For the right triangle shown below:

\(\sin(\theta) = \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}} = \frac35\) so \(\theta = \arcsin\left(\frac35\right)\). It is possible to evaluate other trigonometric functions (such as cosine and tangent) of an angle expressed as an arcsine without explicitly solving for the value of the angle. For example:

\begin{align*}\cos\left(\arcsin\left(\frac35\right)\right) &= \cos(\theta) = \frac{\mbox{adjacent}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}} = \frac45 \\

\tan\left(\arcsin\left(\frac35\right)\right) &= \tan(\theta) = \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{adjacent}} = \frac34\end{align*}

Once you know the sides of the right triangle, you can compute the values of the other trigonometric functions using their standard right-triangle definitions:

\begin{align*}

\sin(\theta) &= \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}}\\

\csc(\theta) &= \frac{1}{\sin(\theta)} = \frac{\mbox{hypotenuse}}{\mbox{opposite}}

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\cos(\theta) &= \frac{\mbox{adjacent}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}}\\

\sec(\theta) &= \frac{1}{\cos(\theta)} = \frac{\mbox{hypotenuse}}{\mbox{adjacent}}

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\tan(\theta) &= \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{adjacent}}\\

\cot(\theta) &= \frac{1}{\tan(\theta)} = \frac{\mbox{adjacent}}{\mbox{opposite}}

\end{align*}

If you are given an angle \(\theta\) as the arcsine of a number, but not given the sides of a right triangle, you can construct your own triangle with the given angle: select values for the opposite side and hypotenuse so the ratio \(\frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}}\) is the value whose arcsine we want: \(\displaystyle \arcsin\left(\frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}}\right)\). You can calculate the length of the third (“adjacent”) side using the Pythagorean Theorem.

Determine the lengths of the sides of a right triangle so one angle is \(\theta = \arcsin\left(\frac{5}{13}\right)\). Use the triangle to determine the values of \(\tan\left(\arcsin\left(\frac{5}{13}\right)\right)\) and \(\csc\left(\arcsin\left(\frac{5}{13}\right)\right)\).

Solution

We want the sine of \(\theta\), the ratio \(\frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}}\), to be \(\frac{5}{13}\) so we can choose the opposite side to be \(5\) and the hypotenuse to be \(13\):

Then \(\sin(\theta) = \frac{5}{13}\), as desired. Using the Pythagorean Theorem, the length of the adjacent side is \(\sqrt{13^2 - 5^2} = 12\). So:

\begin{align*}

\tan(\theta) &= \tan\left(\arcsin\left(\frac{5}{13}\right)\right) = \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{adjacent}} = \frac{5}{12}\\

\csc(\theta) &= \csc\left(\arcsin\left(\frac{5}{13}\right)\right) = \frac{1}{\sin\left(\arcsin\left(\frac{5}{13}\right)\right)} = \frac{1}{\frac{5}{13}} = \frac{13}{5}

\end{align*}

Any choice of values for the opposite side and the hypotenuse will work (for example opposite \(= 500\) and hypotenuse \(=1300\)), as long as the ratio of the opposite side to the hypotenuse is \(\frac{5}{13}\).

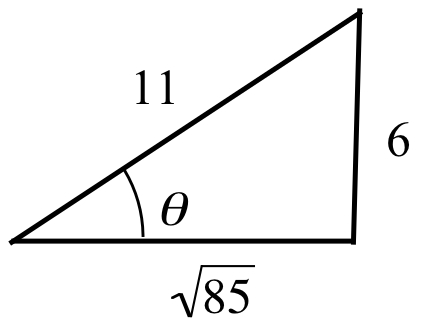

Determine the lengths of the sides of a right triangle so one angle is \(\theta = \arcsin\left(\frac{6}{11}\right)\). Use the triangle to determine the values of \(\tan\left(\arcsin\left(\frac{6}{11}\right)\right)\), \(\csc\left(\arcsin\left(\frac{6}{11}\right)\right)\) and \(\cos\left(\arcsin\left(\frac{6}{11}\right)\right)\).

- Answer

-

With hypotenuse \(11\) and opposite side \(6\), the adjacent side must have length \(\sqrt{11^2-6^2} = \sqrt{85}\), so:

\begin{align*}

\tan\left(\arcsin\left(\frac{6}{11}\right)\right) &= \frac{6}{\sqrt{85}}\\

\csc\left(\arcsin\left(\frac{6}{11}\right)\right) &= \frac{11}{6}\\

\cos\left(\arcsin\left(\frac{6}{11}\right)\right) &= \frac{\sqrt{85}}{11}

\end{align*}

Determine the lengths of the sides of a right triangle so one angle is \(\theta = \arcsin(x)\). Use the triangle to determine the values of \(\tan\left(\arcsin(x)\right)\) and \(\cos\left(\arcsin(x)\right)\).

Solution

We want the sine of \(\theta\), the ratio \(\frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}}\), to be \(x\) so we can choose the opposite side to be \(x\) and the hypotenuse to be \(1\):

Then \(\sin(\theta) = \frac{x}{1} = x\) and, using the Pythagorean Theorem, the length of the adjacent side is \(\sqrt{1 - x^2}\) so that:

\begin{align*}

\tan\left(\arcsin(x)\right) &= \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{adjacent}} = \frac{x}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\\

\cos\left(\arcsin(x)\right) &= \frac{\mbox{adjacent}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}} = \frac{\sqrt{1-x^2}}{1} = \sqrt{1-x^2}

\end{align*}

Other choices for the lengths of the opposite side and hypotenuse, such as \(3x\) and \(3\), will work, but \(x\) and \(1\) are the simplest choices.

Evaluate \(\sec\left(\arcsin( x )\right)\) and \(\csc\left(\arcsin( x )\right)\).

- Answer

-

With hypotenuse \(1\) and opposite side \(x\), the adjacent side must have length \(\sqrt{1^2-x^2} = \sqrt{1-x^2}\), so:

\begin{align*}

\sec\left(\arcsin\left(x\right)\right) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\\

\csc\left(\arcsin\left(x\right)\right) &= \frac{1}{x}

\end{align*}

Inverse Tangent: Solving \(k = \tan(x)\) for \(x\)

The equation \(0.5 = \tan(x)\):

has many solutions: the function \(f(x) = \tan(x)\) is not one-to-one, and its graph reflected across the line \(y=x\):

is not the graph of a function. If, however, we restrict the domain of the tangent function to the interval \(\left(-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right)\), then the restricted \(f(x) = \tan(x)\) is one-to-one and has an inverse function. The graph of this inverse tangent function:

is the reflection about the line \(y = x\) of the (restricted) graph of \(y = \tan(x)\). We call this inverse of the (restricted) tangent function the arctangent and denote it \(\arctan(x)\). For \(x>0\), the number \(\arctan(x)\) is the length of the arc on the unit circle whose tangent is \(x\), and \(\arctan(x)\) is the angle whose tangent is \(x\): \(\tan\left(\arctan(x)\right) = x\).

Many textbooks — and most calculators — use the notation \(\tan^{-1}(x)\) for \(\arctan(x)\). You must be very careful to never interpret \(\tan^{-1}(x)\) to mean:\[\left(\tan(x)\right)^{-1} = \frac{1}{\tan(x)} =\cot(x)\]We avoid the \(\tan^{-1}(x)\) notation for this reason and suggest that you do as well.

For all \(x\) and \(-\frac{\pi}{2} < y < \frac{\pi}{2}\):\[y = \arctan(x) \iff x = \tan(y)\]The domain of \(\arctan(x)\) is \(\left(-\infty, \infty\right)\) and its range is \(\left(-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right)\).

The (restricted) tangent function and the arctangent are inverses:

\begin{align*}

-\infty < x < \infty \ &\Rightarrow \ \tan\left(\arctan(x)\right) = x\\

-\frac{\pi}{2} < y < \frac{\pi}{2} \ &\Rightarrow \ \arctan\left(\tan(y)\right) = y \end{align*}

Right Triangles and Arctangent

For the right triangle in the figure below:

\(\tan(\theta) = \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{adjacent}} = \frac32\) so that \(\theta = \arctan\left(\frac32\right)\), hence:

\begin{align*}

\sin\left(\arctan\left(\frac32\right)\right) &= \sin(\theta) = \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}} = \frac{3}{\sqrt{13}} \approx 0.832\\

\cot\left(\arctan\left(\frac32\right)\right) &= \frac{1}{\tan\left(\arctan\left(\frac32\right)\right)} = \frac{1}{\frac32} = \frac23 \approx 0.667

\end{align*}

Determine the lengths of the sides of a right triangle so that one angle is \(\theta = \arctan\left(\frac34\right)\), then use the triangle to determine the values of \(\sin\left(\arctan\left(\frac34\right)\right)\), \(\cot\left(\arctan\left(\frac34\right)\right)\) and \(\cos\left(\arctan\left(\frac34\right)\right)\).

- Answer

-

With opposite side \(3\) and adjacent side \(4\), the hypotenuse must have length \(\sqrt{3^2+4^2} = \sqrt{25} = 5\), so:

\begin{align*}

\sin\left(\arctan\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)\right) &= \frac{3}{5}\\

\cot\left(\arctan\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)\right) &= \frac{4}{3}\\

\cos\left(\arctan\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)\right) &= \frac{4}{5}

\end{align*}

On a wall 8 feet in front of you, the lower edge of a 5-foot-tall painting rests 2 feet above your eye level:

Represent your viewing angle \(\theta\) using arctangents.

Solution

The viewing angle \(\alpha\) to the bottom of the painting satisfies:\[\tan(\alpha) = \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{adjacent}} = \frac28 \Rightarrow \alpha = \arctan\left(\frac14\right)\]Similarly, the angle \(\beta\) to the top of the painting satisfies:\[\tan(\beta) = \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{adjacent}} = \frac78 \Rightarrow \alpha = \arctan\left(\frac78\right)\]The viewing angle \(\theta\) for the painting is therefore:\[\theta = \beta - \alpha = \arctan\left(\frac78\right) - \arctan\left(\frac14\right) \approx 0.719 - 0.245 = 0.474\]or about \(27^{\circ}\).

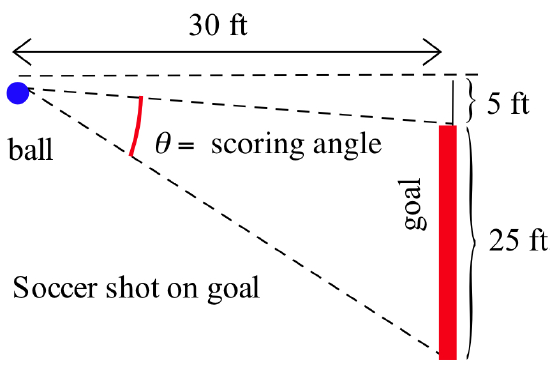

Determine the scoring angle for the soccer player in the figure below:

- Answer

-

\(\tan(\alpha) = \frac{5}{30} = \frac16\) so \(\alpha = \arctan\left(\frac16\right) \approx 0.165\) (or about \(9.46^{\circ}\)). Likewise, \(\tan( \alpha + \theta ) = \frac{30}{30} = 1\) so \(\alpha + \theta = \arctan(1) =\frac{\pi}{4} \approx 0.785\) (or \(45^{\circ}\)). Finally:\[\theta = \left( \alpha + \theta \right) - \alpha \approx 0.785 - 0.165 = 0.62\]or about \(35.54^{\circ}\).

Determine the lengths of the sides of a right triangle so that one angle is \(\theta = \arctan(x)\), then use the triangle to determine the values of \(\sin\left(\arctan( x )\right)\) and \(\cos\left(\arctan( x )\right)\).

Solution

We want the tangent of \(\theta\) (the ratio of opposite to adjacent) to be \(x\), so we can choose the opposite side to be \(x\) and the adjacent side to be \(1\):

Then \(\tan(\theta) = \frac{x}{1} = x\) and, using the Pythagorean Theorem, the length of the hypotenuse is \(\sqrt{1 + x^2}\) so that:

\begin{align*}

\sin\left(\arctan( x )\right) &= \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}} = \frac{x}{\sqrt{1 + x^2}}\\

\cos\left(\arctan( x )\right) &= \frac{\mbox{adjacent}}{\mbox{hypotenuse}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 + x^2}}

\end{align*}

We could have chosen other values for the opposite and adjacent sides (such as \(x^2\) and \(x\)), but \(x\) and \(1\) provide the simplest option.

Evaluate \(\sec\left(\arctan(x)\right)\) and \(\cot\left(\arctan(x)\right)\).

- Answer

-

With opposite side \(x\) and adjacent side \(1\), the hypotenuse must have length \(\sqrt{1^2+x^2} = \sqrt{1+x^2}\), so:

\begin{align*}

\sec\left(\arctan\left(x\right)\right) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{1+x^2}}\\

\cot\left(\arctan\left(x\right)\right) &= \frac{1}{x}

\end{align*}

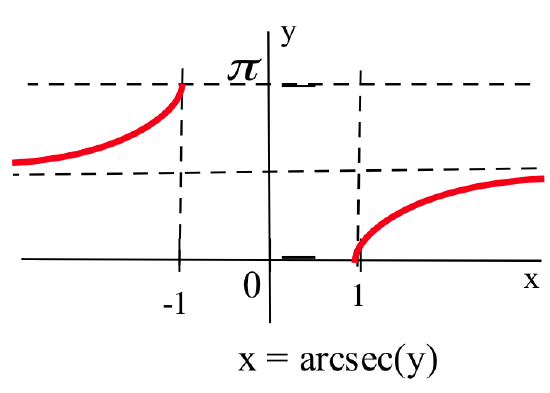

Inverse Secant: Solving \(k = \sec(x)\) for \(x\)

The equation \(2 = \sec(x)\):

has many solutions, but we can create an inverse function for secant — much the same way we did for sine and tangent — by suitably restricting the domain of the secant function so that it becomes a one-to-one function:

The figure above shows the restriction \(0 \leq x \leq \pi\) (\(x \neq \frac{\pi}{2}\)), which results in a one-to-one function that has an inverse. The graph of the inverse function:

is the reflection about the line \(y = x\) of the (restricted) graph of \(y = \sec(x)\). We call this inverse of the (restricted) secant function the arcsecant and denote it \(\mbox{arcsec}(x)\).

If \(\left| x \right| \geq 1\) and \(0 \leq y \leq \pi\) with \(y \neq \frac{\pi}{2}\):\[y = \mbox{arcsec}(x) \iff x = \sec(y)\]The domain of \(\mbox{arcsec}(x)\) is \((-\infty, -1]\cup[1,\infty)\) and the range of \(\mbox{arcsec}(x)\) is \(\left[0,\frac{\pi}{2}\right) \cup \left(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi\right]\).

There are alternate ways to restrict the secant function to get a one-to-one function, and they lead to slightly different definitions of the inverse secant. We chose to use this restriction because it seems more “natural” than the alternatives, it is easier to evaluate on a calculator, and it is the most commonly used.

Many textbooks use the notation \(\sec^{-1}(x)\) for \(\mbox{arcsec}(x)\). You must be very careful to never interpret \(\sec^{-1}(x)\) to mean:\[\left(\sec(x)\right)^{-1} = \frac{1}{\sec(x)} =\cos(x)\]We avoid the \(\sec^{-1}(x)\) notation for this reason and suggest that you do as well.

The (restricted) secant function and the arcsecant are inverses:

\begin{align*}

\left|x\right| \geq 1 \ &\Rightarrow \ \sec\left(\mbox{arcsec}(x)\right) = x\\

0 \leq y \leq \pi \ \left(y\neq\frac{\pi}{2}\right) \ &\Rightarrow \ \mbox{arcsec}\left(\sec(y)\right) = y\end{align*}

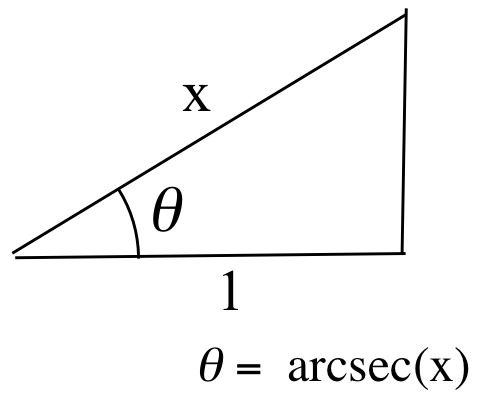

Evaluate \(\tan\left(\mbox{arcsec}(x)\right)\).

Solution

We want the secant of \(\theta\) (the ratio of hypotenuse to adjacent) to be \(x\), so we can choose the hypotenuse to be \(x\) and the adjacent side to be \(1\):

Then \(\sec(\theta) = \frac{x}{1} = x\) and, using the Pythagorean Theorem, the length of the opposite side is \(\sqrt{x^2 - 1}\), so:\[\tan\left(\mbox{arcsec}( x )\right) = \frac{\mbox{opposite}}{\mbox{adjacent}} = \frac{\sqrt{x^2 - 1}}{1} = \sqrt{x^2 - 1}\]As usual, \(x\) and \(1\) are the simplest — but not the only — choices.

Evaluate \(\sin\left(\mbox{arcsec}(x)\right)\) and \(\cot\left(\mbox{arcsec}(x)\right)\).

- Answer

-

FIGURE With hypotenuse \(x\) and adjacent side \(1\), the opposite side must have length \(\sqrt{x^2-1^2} = \sqrt{x^2-1}\), so:

\begin{align*}

\sin\left(\arcsec\left(x\right)\right) &= \frac{\sqrt{x^2-1}}{x}\\

\cot\left(\arcsec\left(x\right)\right) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2-1}}

\end{align*}

The Other Inverse Trigonometric Functions

The inverse tangent and inverse sine functions are by far the most commonly used of the six inverse trigonometric functions in calculus. The inverse secant function turns up less often. The other three inverse trigonometric functions (\(\arccos(x)\), \(\mbox{arccot}(x)\) and \(\mbox{arccsc}(x)\)) can be defined as the inverses of restricted versions of \(\cos(x)\), \(\cot(x)\) and \(\csc(x)\), respectively, but these functions are almost dispensable in calculus. (The reasons for this will become apparent in the next section.)

Calculators and Inverse Trigonometric Functions

Most calculators only have keys for \(\sin^{-1}(x)\), \(\cos^{-1}(x)\) and \(\tan^{-1}(x)\), but the following identities allow you to compute values of the other inverse trigonometric functions.

If: \(x \neq 0\) and \(x\) is in the appropriate domain

then: \(\mbox{arccot}(x) = \arctan\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\), \(\mbox{arcsec}(x) = \arccos\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\) and \(\mbox{arccsc}(x) = \arcsin\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\).

Proof

If \(x \neq 0\), then:\[\tan\left( \mbox{arccot}( x ) \right) = \frac{1}{\cot\left( \mbox{arccot}( x ) \right)} = \frac{1}{x}\]Applying the arctangent function to each side of this equation:\[\arctan\left( \tan\left( \mbox{arccot}( x ) \right) \right) = \arctan\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) \ \Rightarrow \ \mbox{arccot}( x ) = \arctan\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\]Proofs of the other two identities are left to you.

If: \(x \neq 0\) and \(x\) is in the appropriate domain

then: \(\arcsin( x ) + \arccos( x ) = \frac{\pi}{2}\), \(\arctan( x ) + \mbox{arccot}( x ) = \frac{\pi}{2}\) and \(\mbox{arcsec}( x ) + \mbox{arccsc}( x ) = \frac{\pi}{2}\).

Proof

If \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are complementary angles in a right triangle, so that \(\alpha + \beta = \frac{\pi}{2}\), then \(\sin(\alpha) = \cos(\beta)\). Let \(x = \sin( \alpha ) = \cos( \beta )\) so that \(\alpha = \arcsin( x )\) and \(\beta = \arccos( x )\), hence:\[\alpha + \beta = \arcsin( x ) + \arccos( x ) = \frac{\pi}{2}\]This proves the first result for \(0 < x < 1\). You can easily check that the result also holds for \(x = 0\), \(x = 1\) and \(x = -1\). To check that it holds for \(-1 < x < 0\), we need the the next set of identities listed below. Proofs of the other two identities above are left to you.

If: \(x\) is in the appropriate domain

then: \(\arcsin( -x ) = -\arcsin(x)\), \(\arccos( -x ) = \pi - \arccos(x)\), \(\arctan( x ) = - \arctan(x)\), \(\mbox{arcsec}( x ) = \pi-\mbox{arcsec}(x)\), \(\mbox{arccsc}(-x) = -\mbox{arccsc}(x)\) and \(\mbox{arccot}(-x) = -\mbox{arccot}(x)\).

Proof

If \(-1 \leq x \leq 1\), let \(\theta = \arcsin(-x)\) so that \(\sin(\theta) = -x \Rightarrow x = -\sin(\theta) = \sin(-\theta) \Rightarrow \arcsin(x) = -\theta \Rightarrow -\arcsin(x) = \theta = \arcsin(-x)\). This proves the first identity; the others are left to you.

Some programming languages only include a single inverse trigonometric function, \(\arctan(x)\), but it suffices to enable you to evaluate the other five inverse trigonometric functions:

- \(\displaystyle \arcsin(x) = \arctan\left(\frac{x}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\right)\)

- \(\displaystyle \arccos(x) = \frac{\pi}{2} - \arcsin(x) = \frac{\pi}{2} - \arctan\left(\frac{x}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\right)\)

- \(\displaystyle \mbox{arccot}(x) = \arctan\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\)

- \(\displaystyle \mbox{arcsec}(x) = \arctan\left(\sqrt{x^2-1}\right)\)

- \(\displaystyle \mbox{arccsc}(x) = \frac{\pi}{2} - \mbox{arcsec}(x) = \frac{\pi}{2} - \arctan\left(\sqrt{x^2-1}\right)\)

Problems

-

- List the three smallest positive angles \(\theta\) that are solutions of the equation \(\sin(\theta) = 1\).

- Evaluate \(\arcsin( 1 )\) and \(\mbox{arccsc}( 1 )\).

-

- List the three smallest positive angles \(\theta\) that are solutions of the equation \(\tan( \theta ) = 1\).

- Evaluate \(\arctan( 1 )\) and \(\mbox{arccot}( 1 )\).

- Find all \(x\) between \(1\) and \(7\) so that:

- \(\sin(x) = 0.3\)

- \(\sin(x) = -0.4\)

- \(\sin(x) = 0.5\)

- Find all values of \(x\) between \(1\) and \(7\) so that:

- \(\sin(x) = 0.3\)

- \(\sin(x) = -0.4\)

- Find all values of \(x\) between \(2\) and \(7\) so that:

- \(\tan(x) = 3.2\)

- \(\tan(x) = -0.2\)

- Find all values of \(x\) between \(1\) and \(5\) so that:

- \(\tan(x) = 8\)

- \(\tan(x) = -3\)

- In the figure below:

angle \(\theta\) is- the arcsine of what number?

- the arctangent of what number?

- the arcsecant of what number?

- the arccosine of what number?

- In the figure below:

angle \(\theta\) is- the arcsine of what number?

- the arctangent of what number?

- the arcsecant of what number?

- the arccosine of what number?

- For the angle \(\alpha\) in the triangle below:

evaluate:- \(\sin( \alpha )\)

- \(\tan( \alpha )\)

- \(\sec( \alpha )\)

- \(\cos( \alpha )\)

- For the angle \(\beta\) in the triangle Problem 9, evaluate:

- \(\sin( \beta )\)

- \(\tan( \beta )\)

- \(\sec( \beta )\)

- \(\cos( \beta )\)

- For \(\theta = \arcsin\left( \frac27 \right)\), find the exact values of:

- \(\tan( \theta )\)

- \(\cos( \theta )\)

- \(\csc( \theta )\)

- \(\cot( \theta )\)

- For \(\theta = \arctan\left( \frac92 \right)\), find the exact values of:

- \(\sin( \theta )\)

- \(\cos( \theta )\)

- \(\csc( \theta )\)

- \(\cot( \theta )\)

- For \(\theta = \arccos\left( \frac15 \right)\), find the exact values of:

- \(\tan( \theta )\)

- \(\sin( \theta )\)

- \(\csc( \theta )\)

- \(\cot( \theta )\)

- For \(\theta = \arcsin\left( \frac{a}{b} \right)\) with \(0< a < b\), find the exact values of:

- \(\tan( \theta )\)

- \(\cos( \theta )\)

- \(\csc( \theta )\)

- \(\cot( \theta )\)

- For \(\theta = \arctan\left( \frac{a}{b} \right)\) with \(0 < a < b\), find the exact values of:

- \(\tan( \theta )\)

- \(\sin( \theta )\)

- \(\cos( \theta )\)

- \(\cot( \theta )\)

- For \(\theta = \arctan\left( x \right)\), find the exact values of:

- \(\sin( \theta )\)

- \(\cos( \theta )\)

- \(\sec( \theta )\)

- \(\cot( \theta )\)

- Find the exact values of

- \(\sin\left( \arccos( x ) \right)\)

- \(\cos\left( \arcsin( x ) \right)\)

- \(\sec\left( \arccos( x ) \right)\)

- Find the exact values of

- \(\tan\left( \arccos( x ) \right)\)

- \(\cos\left( \arctan( x ) \right)\)

- \(\sec\left( \arcsin( x ) \right)\)

-

- Does \(\arcsin( 1 ) + \arcsin( 1 ) = \arcsin( 2 )\)?

- Does \(\arccos( 1 ) + \arccos( 1 ) = \arccos( 2 )\)?

-

- What is the viewing angle for the tunnel sign in the figure below?

- Use arctangents to describe the viewing angle when the observer is \(x\) feet from the entrance of the tunnel.

- What is the viewing angle for the tunnel sign in the figure below?

-

- What is the viewing angle for the whiteboard in the figure below?

- Use arctangents to describe the viewing angle when the student is \(x\) feet from the wall.

- What is the viewing angle for the whiteboard in the figure below?

- Graph \(y = \arcsin( 2x )\) and \(y = \arctan( 2x )\).

- Graph \(y = \arcsin\left( \frac{x}{2} \right)\) and \(y = \arctan\left( \frac{x}{2} \right)\).

- Which curve is longer, \(y = \sin(x)\) from \(x = 0\) to \(x = \pi\), or \(y = \arcsin(x)\) from \(x = -1\) to \(x = 1\)?

For Problems 25–28, \(\displaystyle \frac{d\theta}{dt}\bigg|_{\theta=1.3} = 12\), and \(\theta\) and \(h\) are related by the given formula. Find \(\displaystyle \frac{dh}{dt}\bigg|_{\theta=1.3}\).

- \(\displaystyle \sin(\theta) = \frac{h}{20}\)

- \(\displaystyle \tan(\theta) = \frac{h}{50}\)

- \(\displaystyle \cos(\theta) = 3h+20\)

- \(\displaystyle 3+\tan(\theta) = 7h\)

For Problems 29–32, \(\displaystyle \frac{dh}{dt}\bigg|_{\theta=1.3} = 4\), and \(\theta\) and \(h\) are related by the given formula. Find \(\displaystyle \frac{d\theta}{dt}\bigg|_{\theta=1.3}\).

- \(\displaystyle \sin(\theta) = \frac{h}{38}\)

- \(\displaystyle \tan(\theta) = \frac{h}{40}\)

- \(\displaystyle \cos(\theta) = 7h-23\)

- \(\displaystyle \tan(\theta) = h^2\)

- You are observing a rocket launch from a position located 4000 feet from the launch pad:

When your observation angle of the rocket is \(\frac{\pi}{3}\), the angle is increasing at \(\frac{\pi}{12}\) feet per second. How fast is the rocket traveling? - You are observing a rocket launch from a position 3000 feet from the launch pad. NASA’s Twitter feed reports that when the rocket is 5000 feet high, its velocity is 100 feet per second.

- What is the angle of elevation of the rocket when it is 5000 feet above the launch pad?

- How fast is the angle of elevation increasing when the rocket is 5000 feet high?

- Refer to the right triangle shown below:

- Angle \(\alpha\) is arcsine of what number?

- Angle \(\beta\) is arccosine of what number?

- For positive numbers \(A\) and \(C\), evaluate \(\arcsin\left( \frac{A}{C} \right) + \arccos\left( \frac{A}{C} \right)\).

- Refer to the right triangle in Problem 35.

- Angle \(\alpha\) is arctangent of what number?

- Angle \(\beta\) is arccotangent of what number?

- For positive numbers \(A\) and \(B\), evaluate \(\arctan\left( \frac{A}{B} \right) + \mbox{arccot}\left( \frac{A}{B} \right)\).

- Refer to the triangle from Problems 35–36.

- Angle \(\alpha\) is arcsecant of what number?

- Angle \(\beta\) is arccosecant of what number?

- For positive numbers \(B\) and \(C\), evaluate \(\mbox{arcsec}\left( \frac{C}{B} \right) + \mbox{arccsc}\left( \frac{C}{B} \right)\).

- Describe the pattern apparent in your results from the previous three problems.

- Refer to the right triangle shown below:

- Angle \(\theta\) is arctangent of what number?

- Angle \(\theta\) is arccotangent of what number?

- Refer to the right triangle from the previous Problem.

- Angle \(\theta\) is arcsine of what number?

- Angle \(\theta\) is arccosecant of what number?

- Refer to the triangle from Problems 39–40.

- Angle \(\theta\) is arccosine of what number?

- Angle \(\theta\) is arcsecant of what number?

- Describe the pattern apparent in your results from the previous three problems.

In Problems 43–51, use a calculator (as necessary) and appropriate identities to compute the given values.

- \(\mbox{arcsec}( 3 )\)

- \(\mbox{arcsec}( -2 )\)

- \(\mbox{arcsec}( -1 )\)

- \(\arccos( 0.5 )\)

- \(\arccos( -0.5 )\)

- \(\arccos( 1 )\)

- \(\mbox{arccot}( 1 )\)

- \(\mbox{arccot}( 0.5 )\)

- \(\mbox{arccot}( -3 )\)

- For the triangle shown below:

- \(\theta = \arctan\left(\, \underline{\quad\quad} \, \right)\)

- \(\theta = \mbox{arccot}\left(\, \underline{\quad\quad} \, \right)\)

- \(\mbox{arccot}\left(\, \underline{\quad\quad} \, \right) = \arctan\left(\, \underline{\quad\quad} \, \right)\)

- For the triangle shown below:

- \(\theta = \arcsin\left(\, \underline{\quad\quad} \, \right)\)

- \(\theta = \arccos\left(\, \underline{\quad\quad} \, \right)\)

- \(\arccos\left(\, \underline{\quad\quad} \, \right) = \arcsin\left(\, \underline{\quad\quad} \, \right)\)

- Prove that \(\displaystyle \mbox{arcsec}(x) = \arccos\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\).

- Prove that \(\displaystyle \mbox{arccsc}(x) = \arcsin\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\).

Using a right triangle you can show that: \begin{align*} &\tan\left( \arcsin( x ) \right) = \frac{x}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}} \\ &\quad \Rightarrow \arcsin( x ) = \arctan\left( \frac{x}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}\right) \end{align*} Imitate this reasoning in Problems 56–57.

- Evaluate \(\tan\left( \mbox{arccot}( x ) \right)\) and use the result to find a formula for \(\mbox{arccot}( x )\) in terms of arctangent.

- Evaluate \(\tan\left(\mbox{arcsec}( x ) \right)\) and use the result to find a formula for \(\mbox{arcsec}( x )\) in terms of arctangent.

- Let \(a = \arctan( x )\) and \(b = \arctan( y )\). Use the identity:\[\tan( a + b ) = \frac{\tan(a) + \tan(b)}{1 - \tan(a)\cdot\tan(b)}\]to show that:\[\arctan( x ) + \arctan( y ) = \arctan\left(\frac{x + y}{1 - xy}\right)\]