0.4: Combinations of Functions

- Page ID

- 209838

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Sometimes a physical or economic situation behaves differently depending on various circumstances. In these situations, a more complicated formula may be needed to describe the situation.

Multiline Definitions of Functions: Putting Pieces Together

Sales Tax: Some states have different rates of sales tax depending on the type of item purchased. As an example, for many years food purchased at restaurants in Seattle was taxed at a rate of 10%, while most other items were taxed at a rate of 9.5% and food purchased at grocery stores had no tax assessed. We can describe this situation by using a multiline function: a function whose defining rule consists of several pieces. Which piece of the rule we need to use will depend on what we buy. In this example, we could define the tax \(T\) on an item that costs \(x\) to be:

\(T ( x ) = \left\{ \begin{array} { r l } { 0 } & { \text { if } x \text { if is the cost of a food at a grocery store} } \\ { 0.10x } & { \text { if } x \text { is the cost of food at a restaurant } } \\ { 0.095x } & { \text { if } x \text { is the cost of any other item } } \end{array} \right.\)

To find the tax on a $2 can of stew, we would use the first piece of the rule and find that the tax is $0. To find the tax on a $30 restaurant bill, we would use the second piece of the rule and find that the tax is $3.00. The tax on a $150 textbook requires using the third rule: the tax would be $14.25.

Wind Chill Index: The rate at which a person’s body loses heat depends on the temperature of the surrounding air and on the speed of the air. You lose heat more quickly on a windy day than you do on a day with little or no wind. Scientists have experimentally determined this rate of heat loss as a function of temperature and wind speed, and the resulting function is called the Wind Chill Index, WCI. The WCI is the temperature on a still day (no wind) at which your body would lose heat at the same rate as on the windy day. For example, the WCI value for \(30^{\circ}\)F air moving at \(15\) miles per hour is \(9^{\circ}\)F: your body loses heat as quickly on a \(30^{\circ}\)F day with a \(15\) mph wind as it does on a \(9^{\circ}\)F day with no wind.

If \(T\) is the Fahrenheit temperature of the air and \(v\) is the speed of the wind in miles per hour, then the WCI can be expressed as a multiline function of the wind speed \(v\) (and of the temperature \(T\)):\[\mbox{WCI} = \left\{\begin{array}{rl} T & \mbox{if }0\leq v \leq 4\\ 91.4 - \frac{10.45 + 6.69\sqrt{v} - 0.447v}{22} (91.5 - T) & \mbox{if }4 < v \leq 45\\ 1.60T - 55 & \mbox{if } v > 45\end{array}\right.\]The WCI value for a still day (\(0 \leq v \leq 4\) mph) is just the air temperature. The WCI for wind speeds above \(45\) mph are the same as the WCI for a wind speed of \(45\) mph. The WCI for wind speeds between \(4\) mph and \(45\) mph decrease as the wind speeds increase. This WCI function depends on two variables: the temperature and the wind speed; but if the temperature is constant, then the resulting formula for WCI only depends on the wind speed. If the air temperature is \(30^{\circ}\)F (\(T = 30\)), then the formula for the Wind Chill Index is:\[\mbox{WCI}_{30} = \left\{\begin{array}{rl} 30^{\circ} & \mbox{if }0\leq v \leq 4\mbox{ mph}\\ 62.19 - 18.70\sqrt{v} +1.25v & \mbox{if }4\mbox{ mph} < v \leq 45\mbox{ mph}\\ -7^{\circ} & \mbox{if } v > 45\mbox{ mph}\end{array}\right.\] The WCI graphs for temperatures of \(40^{\circ}\)F, \(30^{\circ}\)F and \(20^{\circ}\)F appear below:

Figure \(\PageIndex{i}\): From UMAP Module 658, “Windchill,” by William Bosch and L.G.\ Cobb, 1984.

A Hawaiian condo rents for $380 per night during the tourist season (from December 15 through April 30), and for $295 per night otherwise. Define a multiline function that describes these rates.

- Answer

-

\(C(x)\) is the cost for one night on date \(x\): \(C(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} { $380 } & { \text{if }x \text{ is between December 15 and April 30}}\\ { $295 } & { \text{if }x \text{ is any other date}}\end{array}\right.\)

Define \(f(x)\) by:

\(f ( x ) = \left\{ \begin{array} { r l } { 2 } & { \text { if } x < 0 } \\ { 2x } & { \text { if } 0 \leq x < 2 } \\ { 1 } & { \text{ if } 2 < x } \end{array} \right.\)

Evaluate \(f(-3)\),\(f(0)\),\(f(1)\),\(f(4)\) and \(f(2)\). Graph \(y = f(x)\) on the interval \(-1 \leq x \leq 4\).

Solution

To evaluate the function at different values of \(x\), we must first decide which line of the rule applies. If \(x = -3 < 0\), then we need to use the first line, so \(f(-3) = 2\).

When \(x = 0\) or \(x = 1\), we need the second line of the function definition, so \(f(0) = 2(0) = 0\) and \(f(1) = 2(1) = 2\).

At \(x = 4\) we need the third line, so \(f(4) = 1\). Finally, at \(x = 2\), none of the lines apply: the second line requires \(x < 2\) and the third line requires \(2 < x\), so \(f(2)\) is undefined. The graph of \(f(x)\) appears below:

Note the “hole” above \(x = 2\), which indicates \(f(2)\) is not defined by the rule for \(f\).

Define \(g(x)\) by: \(g ( x ) = \left\{ \begin{array} { r l } { x } & { \text { if } x < -1 } \\ { 2 } & { \text{ if } -1 \leq x < 1 } \\ { -x } & { \text{ if } 1 < x } \end{array} \right.\)

Graph \(y = g(x)\) for \(-3 \leq x \leq 6)\) and evaluate \(g(-3)\), \(g(-1)\), \(g(0)\), \(g(\frac12)\), \(g(1)\), \(g(\frac{\pi}{3})\), \(g(2)\), \(g(3)\), \(g(4)\) and \(g(5)\).

- Answer

-

A graph and table appear below:

\(x\) \(g(x)\) \(x\) \(g(x)\) \(-3\) \(-3\) \(\frac{\pi}{3}\) \(-\frac{\pi}{3}\) \(-1\) \(2\) \(2\) \(-2\) \(0\) \(2\) \(3\) \(-3\) \(\frac12\) \(2\) \(4\) undefined \(1\) undefined \(5\) \(1\)

Write a multiline definition for the function whose graph appears below:

- Answer

-

Define \(f(x)\) as: \(f(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} { 1 } & { \text{if }x \leq -1 } \\ { 1-x } & { \text{if }-1 < x \leq 1 } \\ { 2 } & { \text{if } 1 < x } \end{array}\right.\)

We can think of a multiline function as a machine that first examines the input value to decide which line of the function rule to apply:

Composition of Functions: Functions of Functions

Basic functions are often combined with each other to describe more complicated situations. Here we will consider the composition of functions — functions of functions.

The composite of two functions \(f\) and \(g\), written \(f\circ g\), is: \(f\circ g(x) = f\left( g(x) \right)\)

The domain of the composite function \(f\circ g(x) = f\left( g(x) \right)\) consists of those \(x\)-values for which \(g(x)\) and \(f\left( g(x) \right)\) are both defined: we can evaluate the composition of two functions at a point \(x\) only if each step in the composition is defined.

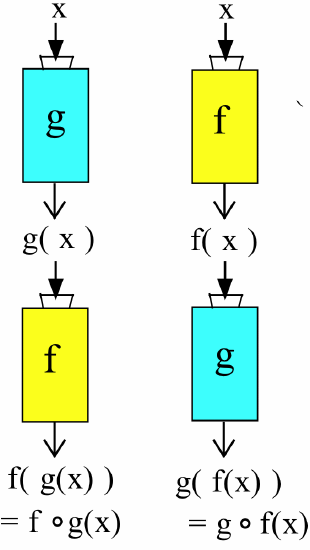

If we think of our functions as machines, then composition is simply a new machine consisting of an arrangement of the original machines. The composition \(f\circ g\) of the function machines \(f\) and \(g\) shown below left is an arrangement of the machines so that the original input \(x\) goes into machine \(g\), the output from machine \(g\) becomes the input into machine \(f\), and the output from machine \(f\) is our final output. The composition of the function machines \(f\circ g(x) = f\left( g(x) \right)\) is only valid if \(x\) is an allowable input into \(g\) (that is, \(x\) is in the domain of \(g\)) and if \(g(x)\) is then an allowable input into \(f\).

The composition \(g\circ f\) involves arranging the machines so the original input goes into \(f\), and the output from \(f\) then becomes the input for \(g\) (shown above right).

For \(f(x) = \sqrt{x - 2}\), \(g(x) = x^2\) and \(h(x) = \left\{ \begin{array} { r l } { 3x } & { \text{if } x < 2 } \\ { x - 1 } & { \text{ if } 2 \leq x } \end{array}\right.\) evaluate \(f\circ g(3)\), \(g\circ f(6)\), \(f\circ h(2)\) and \(h\circ g(-3)\).

Find the formulas and domains of \(f\circ g(x)\) and \(g\circ f(x)\).

Solution

\(f\circ g(3) = f\left( g(3) \right) = f(3^2) = f(9) = \sqrt{9 - 2} = \sqrt{7} \approx 2.646\); \(g\circ f(6) = g\left( f(6) \right) = g(\sqrt{6 - 2}) = g(\sqrt{4}) = g( 2 ) = 2^2 = 4\); \(f\circ h(2) = f\left( h(2) \right) = f( 2 - 1 ) = f( 1 ) = \sqrt{1 - 2} = \sqrt{-1}\), which is undefined; \(h\circ g(-3) = h\left( g(-3) \right) = h( 9 ) = 9 - 1 = 8\); \(f\circ g(x) = f\left( g(x) \right) = f( x^2 ) = \sqrt{x^2 - 2}\), and the domain of \(f\circ g\) consists of those \(x\)-values for which \(x^2 - 2 \geq 0\), so the domain of \(f\circ g\) is all \(x\) such that \(x \geq \sqrt{2}\) or \(x \leq -\sqrt{2}\); \(g\circ f(x) = g\left( f(x) \right) = g( \sqrt{x - 2} ) = \left(\sqrt{x - 2}\right)^2 = x - 2\), but this last equality is true only when \(x-2 \geq 0 \Rightarrow x \geq 2\), so the domain of \(g\circ f\) is all \(x \geq 2\).

For \(f(x) = \frac{x}{x-3}\), \(g(x) = \sqrt{1+x}\) and \( h(x) = \left\{ \begin{array} { r l } {2x } & { \text{ if } x \leq 1 } \\ { 5-x } & { \text{ if } 1 < x } \end{array} \right. \) evaluate \(f\circ g(3)\), \(f\circ g(8)\), \(g\circ f(4)\), \(f\circ h(1)\), \(f\circ h(3)\), \(f\circ h(2)\) and \(h{\circ}g(-1)\).

Find formulas for \(f \circ g(x)\) and \(g\circ f(x)\).

- Answer

-

\(f\circ g(3) = f(2) = \frac{2}{-1} = -2\); \(f\circ g(8) = f(3)\) is undefined; \(g\circ f(4) = g(4) = 5\); \(f\circ h(1) = f(2) = \frac{2}{-1} = -2\); \(f\circ h(3) = f(2) = -2\); \(f\circ h(2) = f(3)\) is undefined; \(h\circ g(-1) = h(0) = 0\); \(f\circ g(x) = f(\sqrt{1 + x}) = \frac{1+x }{\sqrt{1+x} - 3}\), \(g\circ f(x) = g\left(\frac{x}{x-3}\right) = \sqrt{1 + \frac{x}{x-3}}\)

Shifting and Stretching Graphs

Some common compositions are fairly straightforward; you should recognize the effect of these compositions on graphs of the functions.

The figure below shows the graph of \(y = f(x)\):

Graph:

- \(2 + f(x)\)

- \(3\cdot f(x)\)

- \(f(x - 1)\)

Solution

All of the new graphs appear below:

- Adding \(2\) to all of the values of \(f(x)\) rigidly shifts the graph of \(f(x)\) upward \(2\) units.

- Multiplying all of the values of \(f(x)\) by \(3\) leaves all of the roots (zeros) of \(f\) fixed: if \(x\) is a root of \(f\) then \(f(x) = 0 \Rightarrow 3\cdot f(x) = 3(0) = 0\) so \(x\) is also a root of \(3 \cdot f(x)\). If \(x\) is not a root of \(f\), then the graph of \(3f(x)\) looks like the graph of \(f(x)\) stretched vertically by a factor of \(3).

- The graph of \(f(x-1)\) is the graph of \(f(x)\) rigidly shifted \(1\) unit to the right.

We could also get these results by examining the graph of \(y = f(x)\), creating a table of values for \(f(x)\) and the new functions:

| \(x\) | \(f(x)\) | \(2 + f(x)\) | \(3f(x)\) | \(x-1\) | \(f(x-1)\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(-1\) | \(-1\) | \(1\) | \(-3\) | \(-2\) | \(f(-2)\) not defined |

| \(0\) | \(0\) | \(2\) | \(0\) | \(-1\) | \(f(0-1) = -1\) |

| \(1\) | \(1\) | \(3\) | \(3\) | \(0\) | \(f(1-1) = 0\) |

| \(2\) | \(1\) | \(3\) | \(3\) | \(1\) | \(f(2-1) = 1\) |

| \(3\) | \(2\) | \(4\) | \(6\) | \(2\) | \(f(3-1) = 1\) |

| \(4\) | \(0\) | \(2\) | \(0\) | \(3\) | \(f(4-1) = 2\) |

| \(5\) | \(-1\) | \(1\) | \(-3\) | \(4\) | \(f(5-1) = 0\) |

and then graphing those new functions.

If \(k\) is a positive constant, then:

- the graph of \(y = k + f(x)\) will be the graph of \(y = f(x)\) rigidly shifted up by k units

- the graph of \(y = k f(x)\) will have the same roots as the graph of \(f(x)\) and will be the graph of \(y = f(x)\) vertically stretched by a factor of \(k\)

- the graph of \(y = f(x - k)\) will be the graph of \(y = f(x)\) rigidly shifted right by \(k\) units

- the graph of \(y = f(x + k)\) will be the graph of \(y = f(x)\) rigidly shifted left by \(k\) units

The figure below shows the graph of \(y = g(x)\):

Graph:

- \(1 + g(x)\)

- \(2\cdot g(x)\)

- \(g(x - 1)\)

- \(-3\cdot g(x)\)

- Answer

-

See the figure below:

Iteration of Functions

Certain applications feed the output from a function machine back into the same machine as the new input. Each time through the machine is called an iteration of the function.

Suppose \(\displaystyle f(x) = \frac{\frac{5}{x} + x}{2}\) and we start with the input \(x = 4\) and repeatedly feed the output from \(f\) back into \(f\). What happens?

Solution

Creating a table:

| iteration | input | output |

|---|---|---|

| \(1\) | \(4\) | \(f(4) = \frac{\frac54 + 4}{2} = 2.625000000\) |

| \(2\) | \(2.625000000\) | \(f\left( f(4) \right) = \frac{\frac{5}{2.625} + 2.625}{2} = 2.264880952\) |

| \(3\) | \(2.264880952\) | \(f\left( f\left( f(4) \right) \right) = 2.236251251\) |

| \(4\) | \(2.236251251\) | \(2.236067985\) |

| \(5\) | \(2.236067985\) | \(2.236067977\) |

| \(6\) | \(2.236067977\) | \(2.236067977\) |

Once we have obtained the output \(2.236067977\), we will just keep getting the same output (to 9 decimal places). You might recognize this output value as an approximation of \(\sqrt{5}\).

This algorithm always finds \(\pm \sqrt{5}\). If we start with any positive input, the values will eventually get as close to \(\sqrt{5}\) as we want. Starting with any negative value for the input will eventually get us close to \(-\sqrt{5}\). We cannot start with \(x = 0\), as \(\frac50\) is undefined.

What happens if we start with the input value \(x = 1\) and iterate the function \(\displaystyle f(x) = \frac{\frac{9}{x} + x}{2}\) several times? Do you recognize the resulting number? What do you think will happen to the iterates of \(\displaystyle g(x) = \frac{\frac{A}{x} + x}{2}\)? (Try several positive values of \(A\).)

- Answer

-

Using \(\displaystyle f(x) = \frac{\frac{9}{x} + x}{2}\), \(f(1) = \frac{\frac91 + 1}{2} = 5\), \(f(5) = \frac{\frac95 + 5}{2} = 3.4\), \(f(3.4) \approx 3.023529412\) and \(f(3.023529412) \approx 3.000091554\). The next iteration gives \(f(3.000091554) \approx 3.000000001\): these values are approaching \(3\), the square root of \(9\).

With \(A = 6\), \(\displaystyle f(x) = \frac{\frac{6}{x} + x}{2}\), so \(f(1) = \frac{\frac61 + 1}{2} = 3.5\), \(f(3.5) = \frac{\frac{6}{3.5} + 3.5}{2} = 2.607142857\), and the next iteration gives \(f(2.607142857) \approx 2.45425636\). Then \(f(2.45425636) \approx 2.449494372\), \(f(2.449494372) \approx 2.449489743\) and \(f(2.449489743) \approx 2.449489743\) (the output is the same as the input to 9 decimal places): these values are approaching \(2.449489743\), an approximation of \(\sqrt{6}\).

For any positive value \(A\), the iterates of \(\displaystyle f(x) = \frac{\frac{A}{x} +x}{2}\) (starting with any positive \(x\)) will approach \(\sqrt{A}\).

Two Useful Functions: Absolute Value and Greatest Integer

Two functions (one of which should be familiar to you, the other perhaps not) possess useful properties that let us describe situations in which an object abruptly changes direction or jumps from one value to another value. Their graphs will have corners and breaks, respectively.

The absolute value function evaluated at a number \(x\), \(y = f(x) = \left|x\right|\), is the distance between the number \(x\) and \(0\).

Some calculators and computer programming languages represent the absolute value function by \(\mbox{abs}(x)\) or \(\mbox{ABS}(x)\).

If \(x\) is greater than or equal to \(0\), then \(| x |\) is simply \(x - 0 = x\). If \(x\) is negative, then \(| x |\) is \(0 - x = -x = -1\cdot x\), which is positive because: \[-1\cdot(\mbox{negative number}) = \mbox{a positive number}\]

\(\left| x \right| = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} {x } & {\text{if }x\geq 0 } \\ {-x } & {\text{if }x<0} \end{array}\right.\)

We can also write: \(\left|x\right| = \sqrt{x^2}\).

The domain of \(y = f(x) = \left| x \right|\) consists of all real numbers. The range of \(f(x) = \left| x \right|\) consists of all numbers larger than or equal to zero (all non-negative numbers). The graph of \(y = f(x) = \left| x \right|\) has no holes or breaks, but it does have a sharp corner at \(x = 0\):

The absolute value will be useful for describing phenomena such as reflected light and bouncing balls that change direction abruptly or whose graphs have corners. The absolute value function has a number of properties we will use later.

For all real numbers \(a\) and \(b\):

- \(\left| a \right| = 0\cdot \left| a \right| = 0\) if and only if \(a = 0\)

- \(\left| ab \right| = \left| a \right| \cdot \left| b \right|\)

- \(\left| a + b \right| \leq \left| a \right| + \left| b \right|\)

This last property is widely known as the triangle inequality.

Taking the absolute value of a function has an interesting effect on the graph of the function: for any function \(f(x)\), we have:

\(\left| f(x) \right| = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} { f(x) } & { \text{if } f(x)\geq 0 } \\ {-f(x) } & { \text{if } f(x)<0 } \end{array}\right.\)

In other words, if \(f(x) \geq 0\), then \(\left| f(x) \right| = f(x)\), so the graph of \(\left| f(x) \right|\) is the same as the graph of \(f(x)\). If \(f(x) < 0\), then \(\left| f(x) \right| = -f(x)\), so the graph of \(\left| f(x) \right|\) is just the graph of \(f(x)\) “flipped” about the \(x\)-axis, and it lies above the \(x\)-axis. The graph of \(\left|f(x)\right|\) will always be on or above the \(x\)-axis.

The figure below shows the graph of \(f(x)\):

Graph:

- \(\left| f(x) \right|\)

- \(\left| 1 + f(x) \right|\)

- \(1+\left| f(x) \right|\)

Solution

The graphs appear below:

In (b), we rigidly shift the graph of \(f\) up \(1\) unit before taking the absolute value. In (c), we take the absolute value before rigidly shifting the graph up \(1\) unit.

The figure below shows the graph of \(g(x)\):

Graph:

- \(\left| g(x) \right|\)

- \(\left| g(x-1) \right|\)

- \(g\left(\left|x\right|\right)\)

- Answer

-

The figure below shows some intermediate steps and final graphs:

The greatest integer function (or floor function) evaluated at a number \(x\), \(y = f(x) = \left\lfloor x \right\rfloor\), is the largest integer less than or equal to \(x\).

The value of \(\left\lfloor x \right\rfloor\) is always an integer and \(\left\lfloor x \right\rfloor\) is always less than or equal to \(x\). For example, \(\left\lfloor 3.2 \right\rfloor = 3\), \(\left\lfloor 3.9 \right\rfloor = 3\) and \(\left\lfloor 3 \right\rfloor = 3\). If \(x\) is positive, then \(\left\lfloor x \right\rfloor\) truncates \(x\) (drops the fractional part of \(x\)). If \(x\) is negative, the situation is different: \(\left\lfloor -4.2 \right\rfloor \neq -4\) because \(-4\) is not less than or equal to \(-4.2\): \(\left\lfloor -4.2 \right\rfloor = -5\), \(\left\lfloor -4.7 \right\rfloor = -5\) and \(\left\lfloor -4 \right\rfloor = -4\).

Historically, many textbooks have used the square brackets \(\left[\mbox{ }\right]\) to represent the greatest integer function, while calculators and many programming languages use \(\mbox{INT}(x)\) or \(\mbox{floor}(x)\).

\(\left\lfloor x \right\rfloor = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} {x } & {\text{if } x \text{ is an integer} } \\ { \text{largest integer strictly less than } x } & {\text{if }x \text{ is not an integer} } \end{array}\right.\)

The domain of \(f(x) = \left\lfloor x \right\rfloor\) is all real numbers. The range of \(f(x) = \left\lfloor x \right\rfloor\) is only the integers. The graph of \(y = f(x) = \left\lfloor x \right\rfloor\) appears below.

![A graph of the greatest integer function, y = INT(x) or y = [x]. It is a step function composed of horizontal line segments. Each segment has a solid (closed) circle on the left, indicating the function value includes that integer, and an open circle on the right, indicating it excludes the next integer. The steps shown are at y = -1 (from x=-2 to x=-1, open circle at x=-1), y = 0 (from x=0 to x=1, open circle at x=1), y = 1 (from x=1 to x=2, open circle at x=2), and y = 2 (from x=2 to x=3, open circle at x=3).](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/139094/fig004_14.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=364&height=292)

It has a jump break{\thinspace}---{\thinspace}a “step” — at each integer value of \(x\), so \(f(x) = \left\lfloor x \right\rfloor\) is called a {\bf step function}. Between any two consecutive integers, the graph is horizontal with no breaks or holes.

The greatest integer function is useful for describing phenomena that change values abruptly, such as postage rates as a function of weight. As of January 26, 2014, the cost to mail a first-class retail “flat” (such as a manila envelope) was \$0.98 for the first ounce and another $0.21 for each additional ounce.

The \(\left\lfloor x \right\rfloor\) function can also be used for functions whose graphs are “square waves,” such as the on and off of a flashing light.

Graph \(y = \left\lfloor 1+0.5\sin(x) \right\rfloor\).

Solution

One way to create this graph is to first graph \(y = 1 + 0.5\sin(x)\), the thin curve in figure below:

and then apply the greatest integer function to \(y\) to get the thicker “square wave” pattern.

Sketch the graph of \(y = \left\lfloor x^2 \right\rfloor\) for \(-2 \leq x \leq 2\).

- Answer

-

The figure below shows the graph of \(y = x^2\) and the (thicker) graph of \(y = \left\lfloor x^2 \right\rfloor\):

A Really “Holey” Function

The graph of \(\left\lfloor x\right\rfloor\) has a break or jump at each integer value, but how many breaks can a function have? The next function illustrates just how broken or “holey” the graph of a function can be.

Define a function \(h(x)\) as: \(h(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} {2} & { \text{if }x\text{ is a rational number} } \\ {1} & { \text{if }x\text{ is an irrational number} } \end{array}\right.\)

Then \(h( 3 ) = 2\), \(h\left(\frac53\right) = 2\) and \(h\left(-\frac25\right) = 2\), because \(3\), \(\frac53\) and \(-\frac25\) are all rational numbers. Meanwhile, \(h( \pi ) = 1\), \(h(\sqrt{7}) = 1\) and \(h(\sqrt{2}) = 1\), because \(\pi\), \(\sqrt{7}\) and \(\sqrt{2}\) are all irrational numbers. These and some other points are plotted in the figure below:

In order to analyze the behavior of \(h(x)\) the following fact about rational and irrational numbers is useful.

Every interval contains both rational and irrational numbers.

Equivalently: If \(a\) and \(b\) are real numbers and \(a < b\), then there is:

- a rational number \(R\) between \(a\) and \(b\) (\(a < R < b\))

- an irrational number \(I\) between \(a\) and \(b\) (\(a < I < b\)

The above fact tells us that between any two places where \(y = h(x) = 1\) (because \(x\) is rational) there is a place where \(y = h(x)\) is \(2\), because there is an irrational number between any two distinct rational numbers. Similarly, between any two places where \(y = h(x) = 2\) (because \(x\) is irrational) there is a place where \(y = h(x) = 1\), because there is a rational number between any two distinct irrational numbers.

The graph of \(y = h(x)\) is impossible to actually draw, because every two points on the graph are separated by a hole. This is also an example of a function that your computer or calculator cannot graph, because in general it can not determine whether an input value of \(x\) is irrational.

Sketch the graph of \(g(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} {2} & { \text{if }x\text{ is a rational number} } \\ {x} & { \text{if }x\text{ is an irrational number} } \end{array}\right.\)

Solution

A sketch of the graph of \(y = g(x)\) appears below:

When \(x\) is rational, the graph of \(y = g(x)\) looks like the “holey” horizontal line \(y = 2\). When \(x\) is irrational, the graph of \(y = g(x)\) looks like the “holey” line \(y = x\).

Sketch the graph of \(h(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} { \sin(x) } & { \text{if }x\text{ is a rational number} }\\ { x } & { \text{if }x\text{ is an irrational number} } \end{array}\right.\)

- Answer

-

The figure below shows the “holey” graph of \(y = x\) with a hole at each rational value of \(x\) and the “holey” graph of \(y = \sin(x)\) with a hole at each irrational value of \(x\). Together they form the graph of \(r(x)\).

(This is a very crude image, since we can’t really see the individual holes, which have zero width.)

Problems

- If \(T\) is the Celsius temperature of the air and \(v\) is the speed of the wind in kilometers per hour, then:

\( \text{WCI} = \left\{\begin{array}{rl} {T } & { \text{if }0\leq v \leq 6.5}\\ {33 - \frac{10.45 + 5.29\sqrt{v} - 0.279v}{22} (33 - T) } & { \text{if }6.5 < v \leq 72 }\\ {1.6T - 19.8 } & { \text{if } v > 72 } \end{array}\right.\)- Determine the Wind Chill Index for:

- a temperature of \(0^\circ\)C and a wind speed of \(49\) km/hr

- a temperature of \(11^\circ\)C and a wind speed of \(80\) km/hr.

- Write a multiline function definition for the WCI if the temperature is \(11^{\circ}\)C.

- Determine the Wind Chill Index for:

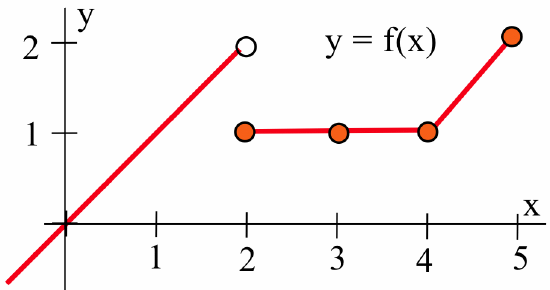

- Use the graph of \(y = f(x)\) below to evaluate \(f(0)\), \(f(1)\), \(f(2)\), \(f(3)\), \(f(4)\) and \(f(5)\):

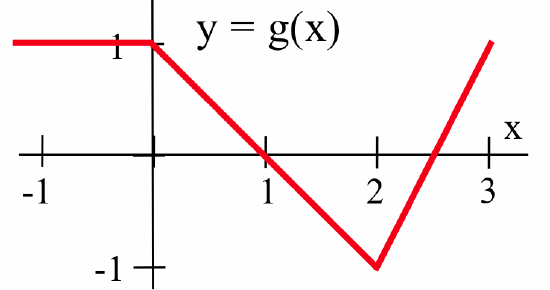

Write a multiline function definition for \(f\). - Use the graph of \(y = g(x)\) below to evaluate \(g(0)\), \(g(1)\), \(g(2)\), \(g(3)\), \(g(4)\) and \(g(5)\):

Write a multiline function definition for \(g\). - Use the values given in the table below, along with \(h(x) = 2x + 1\), to determine the missing values of \(f\circ g\), \(g\circ f\) and \(h\circ g\).

\(x\) \(f(x)\) \(g(x)\) \(f\circ g(x)\) \(g\circ f(x)\) \(h\circ g(x)\) \(-1\) \(2\) \(0\) \(0\) \(1\) \(2\) \(1\) \(-1\) \(1\) \(2\) \(0\) \(2\) - Use the graphs shown below:

and the function \(h(x) = x - 2\) to determine the values of:- \(f\left( f( 1 ) \right)\), \(f\left( g( 2 ) \right)\), \(f\left( g( 0 ) \right)\), \(f\left( g( 1 ) \right)\)

- \(g\left( f( 2 ) \right)\), \(g\left( f( 3 ) \right)\), \(g\left( g( 0 ) \right)\), \(g\left( f( 0 ) \right)\)

- \(f\left( h( 3 ) \right)\), \(f\left( h( 4 ) \right)\), \(h\left( g( 0 ) \right)\), \(h\left( g( 1 ) \right)\)

- Use the graphs shown below:

and the function \(h(x) = 5 - 2x\) to determine the values of:- \(h\left( f( 0 ) \right)\), \(f\left( h( 1 ) \right)\), \(f\left( g( 2 ) \right)\), \(f\left( f( 3 ) \right)\)

- \(g\left( f( 0 ) \right)\), \(g\left( f( 1 ) \right)\), \(g\left( h( 2 ) \right)\), \(h\left( f( 3 ) \right)\)

- \(f\left( g( 0 ) \right)\), \(f\left( g( 1 ) \right)\), \(f\left( h( 2 ) \right)\), \(h\left( g( 3 ) \right)\)

- Defining \(h(x) = x - 2\), \(f(x)\) as:

\(f(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} {3} & {\text{if }x < 1}\\ {x-2} & {\text{if }1 \leq x < 3}\\ {1} & {\text{if }3 \leq x}\end{array}\right.\)

and \(g(x)\) as:

\(g(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} {x^2-3} & {\text{if }x < 0}\\ {\left\lfloor x \right\rfloor } & { \text{if }0 \leq x } \end{array}\right.\)- evaluate \(f(x)\), \(g(x)\) and \(h(x)\) for \(x = -1\), \(0\), \(1\), \(2\), \(3\) and \(4\).

- evaluate \(f\left( g( 1 ) \right)\), \(f\left( h( 1 ) \right)\), \(h\left( f( 1 ) \right)\), \(f\left( f( 2 ) \right)\), \(g\left( g( 3.5 ) \right)\).

- graph \(f(x)\), \(g(x)\) and \(h(x)\) for \(-5 \leq x \leq 5\).

- Defining \(h(x) = 3\), \(f(x)\) as:

\(f(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} {x+1} & {\text{if }x < 1}\\ {1 } & {\text{if }1 \leq x < 3}\\ {2-x} & {\text{if }3 \leq x}\end{array}\right.\)

and \(g(x)\) as:

\(g(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} {\left|x+1\right|} & {\text{if }x < 0}\\ {2x} & {\text{if }0 \leq x}\end{array}\right.\)- evaluate \(f(x)\), \(g(x)\) and \(h(x)\) for \(x = -1\), \(0\), \(1\), \(2\), \(3\) and \(4\).

- evaluate \(f\left( g( 1 ) \right)\), \(f\left( h( 1 ) \right)\), \(h\left( f( 1 ) \right)\), \(f\left( f( 2 ) \right)\), \(g\left( g( 3.5 ) \right)\).

- graph \(f(x)\), \(g(x)\) and \(h(x)\) for \(-5 \leq x \leq 5\).

- You are planning to take a one-week vacation in Europe, and the tour brochure says that Monday and Tuesday will be spent in England, Wednesday in France, Thursday and Friday in Germany, and Saturday and Sunday in Italy. Let \(L(d)\) be the location of the tour group on day \(d\) and write a multiline function definition for \(L(d)\).

- A state has just adopted the following state income tax system: no tax on the first $10,000 earned, 1% of the next $10,000 earned, 2% of the next $20,000 earned, and 3% of all additional earnings. Write a multiline function definition for \(T(x)\), the state income tax due on earnings of \(x\) dollars.

- Write a multiline function definition for the curve \(y = f(x)\) shown below:

- Define \(B(x)\) to be the area of the rectangle whose lower left corner is at the origin and whose upper right corner is at the point \(\left(x, f(x) \right)\) for the function \(f\) shown below:

For example, \(B(3)=6\). Evaluate \(B(1)\), \(B(2)\), \(B(4)\) and \(B(5)\). - Define \(B(x)\) to be the area of the rectangle whose lower left corner is at the origin and whose upper right corner is at the point \(\left(x, \frac{1}{x}\right)\).

- Evaluate \(B(1)\), \(B(2)\) and \(B(3)\).

- Show that \(B(x) = 1\) for all \(x > 0\).

- For \(f(x) = \left| 9 - x \right|\) and \(g(x) = \sqrt{x - 1}\):

- evaluate \(f\circ g( 1 )\), \(f \circ g( 3 )\), \(f\circ g( 5 )\), \(f \circ g( 7 )\), \(f\circ g( 0 )\).

- evaluate \(f \circ f( 2 )\), \(f \circ f( 5 )\), \(f\circ f( -2 )\).

- Does \(f\circ f(x) = \left|x \right|\) for all values of \(x\)?

- The function \(g(x)\) is graphed below:

Graph:- \(g(x) - 1\)

- \(g( x-1 )\)

- \(\left| g(x) \right|\)

- \(\left\lfloor g(x) \right\rfloor\)

- The function \(f(x)\) is graphed below:

Graph:- \(f(x) - 2\)

- \(f( x-2 )\)

- \(\left| f(x) \right|\)

- \(\left\lfloor f(x) \right\rfloor\)

- Find \(A\) and \(B\) so that \(f\left( g(x) \right) = g\left( f(x) \right)\) when:

- \(f(x) = 3x + 2\) and \(g(x) = 2x + A\)

- \(f(x) = 3x + 2\) and \(g(x) = Bx - 1\)

- Find \(C\) and \(D\) so that \(f\left( g(x) \right) = g\left( f(x) \right)\) when:

- \(f(x) = Cx + 3\) and \(g(x) = Cx-1\)

- \(f(x) = 2x + D\) and \(g(x) = 3x+D\)

- Graph \(y = f(x) = x - \left\lfloor x\right\rfloor\) for \(-1 \leq x \leq 3\). This function is called the “fractional part of \(x\)” and its graph an example of a “sawtooth” graph.

- The function \(f(x) = \left\lfloor x + 0.5\right\rfloor\) rounds off \(x\) to the nearest integer, while \(\displaystyle g(x) = \frac{\left\lfloor 10x + 0.5\right\rfloor}{10}\) rounds off \(x\) to the nearest tenth (the first decimal place). What function will round off \(x\) to:

- the nearest hundredth (two decimal places)?

- the nearest thousandth (three decimal places)?

- Modify the function in Example 6 to produce a “square wave” graph with a “long on, short off, long on, short off” pattern.

- Many computer languages contain a “signum” or “sign” function defined by:

\(\mbox{sgn}(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} {1} & {\text{if }x > 0}\\ {0} & {\text{if }x=0}\\ {-1} & {\text{if }x <0}\end{array}\right.\)- Graph \(\mbox{sgn}( x )\).

- Graph \(\mbox{sgn}( x - 2 )\).

- Graph \(\mbox{sgn}( x - 4 )\).

- Graph \(\mbox{sgn}( x - 2 ) \cdot \mbox{sgn}( x - 4 )\).

- Graph \(1 - \mbox{sgn}( x - 2 ) \cdot \mbox{sgn}( x - 4 )\).

- For real numbers \(a\) and \(b\) with \(a < b\), describe the graph of \(1 - \mbox{sgn}( x - a ) \cdot \mbox{sgn}( x - b )\).

- Define \(g(x)\) to be the slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(y = f(x)\) at \((x,y)\), with \(y = f(x)\) shown here:

- Estimate \(g(1)\), \(g(2)\), \(g(3)\) and \(g(4)\).

- Graph \(y = g(x)\) for \(0 \leq x \leq 4\).

- Define \(h(x)\) to be the slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(y = f(x)\) at \((x,y)\), with \(y = f(x)\) shown here:

- Estimate \(h(1)\), \(h(2)\), \(h(3)\) and \(h(4)\).

- Graph \(y = h(x)\) for \(0 \leq x \leq 4\).

- Using the cos (cosine) button on your calculator several times produces iterates of \(f(x) = \cos(x)\). What number will the iterates approach if you use the cos button 20 or 30 times starting with:

- \(x = 1\)?

- \(x = 2\)?

- \(x = 10\)?

- Let \(f(x) = 1 + \sin(x)\).

- What happens if you start with \(x = 1\) and repeatedly feed the output from \(f\) back into \(f\)?

- What happens if you start with \(x = 2\) and examine the iterates of \(f\)?

- Starting with \(x = 1\), do the iterates of \(f(x) = \frac{x^ 2 + 1}{2x}\) approach a number? What happens if you start with \(x = 0.5\) or \(x = 4\)?

- Let \(f(x) = \frac{x}{2} + 3\).

- What are the iterates of \(f\) if you start with \(x = 2\)? \(x = 4\)? \(x = 6\)?

- Find a number \(c\) so that \(f(c) = c\). This value of \(c\) is called a fixed point of \(f\).

- Find a fixed point of \(g(x) = \frac{x}{2} + A\).

- Let \(f(x) = \frac{x}{3} + 4\).

- What are the iterates of \(f\) if you start with \(x = 2\)? \(x = 4\)? \(x = 6\)?

- Find a number \(c\) so that \(f(c) = c\).

- Find a fixed point of \(g(x) = \frac{x}{3} + A\).

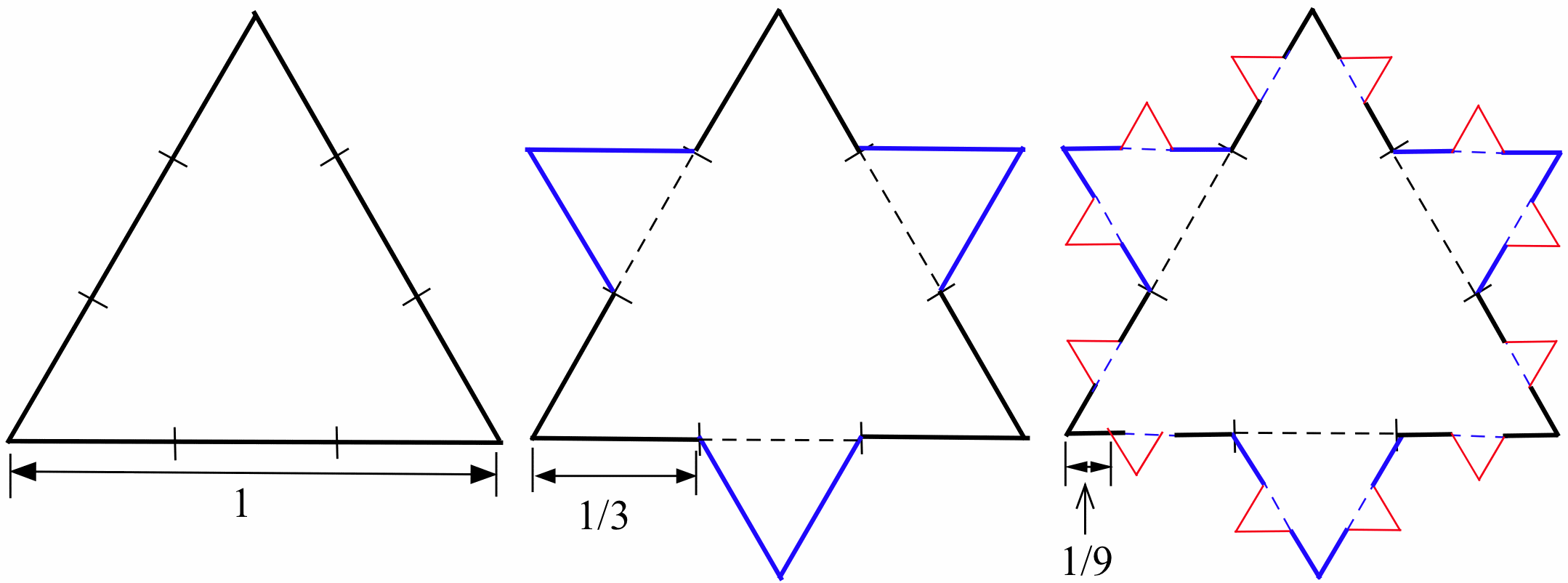

- Some iterative procedures are geometric rather than numerical. Start with an equilateral triangle with sides of length \(1\), as shown at left in the figure below.

- Remove the middle third of each line segment.

- Replace the removed portion with two segments with the same length as the removed segment.

Repeat these steps several more times, each time removing the middle third of each line segment and replacing it with two new segments. What happens to the length of the shape with each iteration? (The result of iterating over and over with this procedure is called Koch’s Snowflake, named for Helga von Koch.) - Sketch the graph of: \(p(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} {3-x} & {\text{if }x \text{ is a rational number}}\\ {1} & {\text{if }x \text{ is an irrational number}}\end{array}\right.\)

- Sketch the graph of: \(q(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} {x^2} & {\text{if }x \text{ is a rational number}}\\ {x+11} & {\text{if }x \text{ is an irrational number}}\end{array}\right.\)