2.0: Introduction to Derivatives

- Page ID

- 212010

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)This section begins with a very graphical approach to slopes of tangent lines. It then examines the problem of finding the slopes of the tangent lines for a single function, \(y = x^2\), in some detail — and illustrates how these slopes can help us solve fairly sophisticated problems.

Slopes of Tangent Lines: Graphically

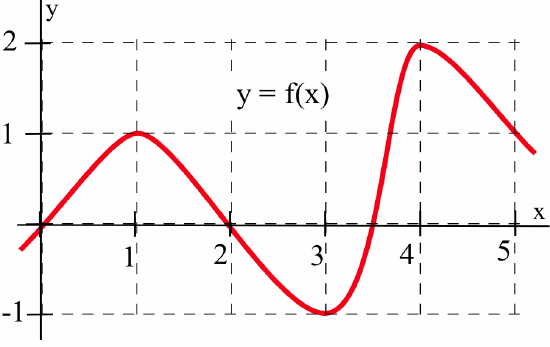

The figure below shows the graph of a function \(y = f(x)\).

We can use the information in the graph to fill in the table:

| \(x\) | \(y = f(x)\) | \(m(x)\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(0\) | \(0\) | \(1\) |

| \(1\) | \(1\) | \(0\) |

| \(2\) | \(0\) | \(-1\) |

| \(3\) | \(-1\) | \(0\) |

| \(4\) | \(1\) | \(1\) |

| \(5\) | \(2\) | \(\frac12\) |

where \(m(x)\) is the (estimated) slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(y=f(x)\) at the point \((x,y)\). We can estimate the values of \(m(x)\) at some non-integer values of \(x\) as well: \(m(0.5) \approx 0.5\) and \(m(1.3) \approx -0.3\), for example. We can even say something about the behavior of \(m(x)\) over entire intervals: if \(0 < x < 1\), then \(m(x)\) is positive, for example.

The values of \(m(x)\) definitely depend on the values of \(x\) (the slope varies as \(x\) varies, and there is at most one slope associated with each value of \(x\)) so \(m(x)\) is a function of \(x\). We can use the results in the table to help sketch a graph of the function \(m(x)\):

A graph of \(y = f(x)\) appears below. Set up a table of (estimated) values for \(x\) and \(m(x)\), the slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(y=f(x)\) at the point \((x,y)\), and then sketch a graph of the function \(m(x)\).

- Answer

-

Approximate values of \(m(x)\) appear in the table:

\(x\) \(f(x)\) \(m(x)\) \(0\) \(2\) \(-1\) \(1\) \(1\) \(-1\) \(2\) \(\frac13\) \(0\) \(3\) \(1\) \(1\) \(4\) \(\frac32\) \(\frac12\) \(5\) \(1\) \(-2\) The figure shows a graph of \(m(x)\) below a graph of \(y=f(x)\):

In some applications, we need to know where the graph of a function \(f(x)\) has horizontal tangent lines (that is, where the slope of the tangent line equals \(0\)). The slopes of the lines tangent to graph of \(y = f(x)\) in Practice \(\PageIndex{1}\) are \(0\) when \(x = 2\) or \(x \approx 4.25\).

At what values of \(x\) does the graph of \(y = g(x)\) (below) have horizontal tangent lines?

- Answer

-

The tangent lines to the graph of \(g\) are horizontal (slope \(= 0\)) when \(x \approx -1\), \(1\), \(2.5\) and \(5\).

The graph of the height of a rocket at time \(t\) appears below:

Sketch a graph of the velocity of the rocket at time \(t\). (Remember that instantaneous velocity corresponds to the slope of the line tangent to the graph of position or height function.)

Solution

The top figure below shows some sample tangent line segments:

while the bottom figure shows the velocity of the rocket. (What so you think happened at time \(t = 8\)?)

The graph below shows the temperature during a summer day in Chicago.

Sketch a graph of the rate at which the temperature is changing at each moment in time. (As with instantaneous velocity, the instantaneous rate of change for the temperature corresponds to the slope of the line tangent to the temperature graph.

- Answer

-

The figure below shows a graph of the approximate rate of temperature change (slope) below a graph of the temperature.

The function \(m(x)\), the slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(y = f(x)\) at \(( x, f(x) )\), is called the derivative of \(f(x)\).

We used the idea of the slope of the tangent line all throughout Chapter 1. In Section 2.1, we will formally define the derivative of a function and begin to examine some of its properties, but first let’s see what we can do when we have a formula for \(f(x)\).

Tangents to \(y = x^2\)

When we have a formula for a function, we can determine the slope of the tangent line at a point \(( x, f(x) )\):

by calculating the slope of the secant line through the points \(( x, f(x) )\) and \(( x+h, f(x+h) )\):\[m_{\mbox{sec}} = \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{(x+h) - (x)}\]and then taking the limit of \(m_{\mbox{sec}}\) as \(h\) approaches \(0\):\[m_{\mbox{tan}} \ = \ \lim_{h\to 0} \, m_{\mbox{sec}} \ = \ \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{(x+h) - (x)}\]

Find the slope of the line tangent to the graph of the function \(y = f(x) = x^2\) at the point \((2,4)\).

Solution

In this example, \(x = 2\), so \(x + h = 2 + h\) and \(f(x + h) = f(2+h) = (2+h)^2\). The slope of the tangent line at \((2,4)\) is \begin{align*} m_{\mbox{tan}} &= \lim_{h\to 0} \, m_{\mbox{sec}} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{f(2+h) - f(2)}{(2+h) - (2)}\\ &= \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{(2+h)^2 - 2^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{4+4h+h^2-4}{h}\\ &= \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{4h+h^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, [4+h] = 4 \end{align*} The line tangent to \(y = x^2\) at the point \((2,4)\) has slope \(4\).

We can use the point-slope formula for a line to find an equation of this tangent line:\[y - y_0 = m(x - x_0) \ \Rightarrow \ y - 4 = 4(x - 2) \ \Rightarrow \ y = 4x - 4\nonumber\]

Use the method of Example \(\PageIndex{2}\) to show that the slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(y = f(x) = x^2\) at the point \((1,1)\) is \(m_{\mbox{tan}} = 2\). Also find the values of \(m_{\mbox{tan}}\) at \((0,0)\) and \((-1,1)\).

- Answer

-

At \((1,1)\), the slope of the tangent line is:

\begin{align*}

m_{\mbox{tan}} &= \lim_{h\to 0} \, m_{\mbox{sec}} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{f(1+h) - f(1)}{(1+h) - (1)}\\

&= \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{(1+h)^2 - 1^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{1+2h+h^2-1}{h}\\

&= \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{2h+h^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, [2+h] = 2

\end{align*}

so the line tangent to \(y = x^2\) at the point \((1,1)\) has slope \(2\). At \((0,0)\):

\begin{align*}

m_{\mbox{tan}} &= \lim_{h\to 0} \, m_{\mbox{sec}} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{f(0+h) - f(1)}{(0+h) - (0)}\\

&= \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{(0+h)^2 - 0^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{h^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, h = 0

\end{align*}

so the line tangent to \(y = x^2\) at \((0,0)\) has slope \(0\). At \((-1,1)\):

\begin{align*}

m_{\mbox{tan}} &= \lim_{h\to 0} \, m_{\mbox{sec}} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{f(-1+h) - f(-1)}{(-1+h) - (-1)}\\

&= \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{(-1+h)^2 - (-1)^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{1-2h+h^2-1}{h}\\

&= \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{-2h+h^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, [-2+h] = -2

\end{align*}

so the line tangent to \(y = x^2\) at the point \((-1,1)\) has slope \(-2\).

It is possible to compute the slopes of the tangent lines one point at a time, as we have been doing, but that is not very efficient. You should have noticed in Practice 4 that the algebra for each point was very similar, so let”s do all the work just once, for an arbitrary point \(( x, f(x) ) = ( x, x^2 )\) and then use the general result to find the slopes at the particular points we’re interested in.

The slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(y = f(x) = x^2\) at the arbitrary point \(( x, x^2 )\) is: \begin{align*} m_{\mbox{tan}} &= \lim_{h\to 0} \, m_{\mbox{sec}} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{(x+h) - (x)}\\ &= \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{(x+h)^2 - x^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{x^2+2xh+h^2-x^2}{h}\\ &= \lim_{h\to 0} \, \frac{2xh+h^2}{h} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, \left[2x+h\right] = 2x \end{align*} The slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(y = f(x) = x^2\) at the point \((x, x^2)\) is \(m_{\mbox{tan}} = 2x\). We can use this general result at any value of \(x\) without going through all of the calculations again. The slope of the line tangent to \(y = f(x) = x^2\) at the point \((4, 16)\) is \(m_{\mbox{tan}} = 2(4) = 8\) and the slope at \((p, p^2)\) is \(m_{\mbox{tan}} = 2(p) = 2p\). The value of \(x\) determines the location of our point on the curve, \((x, x^2)\), as well as the slope of the line tangent to the curve at that point, \(m_{\mbox{tan}} = 2x\). The slope \(m_{\mbox{tan}} = 2x\) is a function of \(x\) and is called the derivative of \(y = x^2\).

Simply knowing that the slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(y = x^2\) is \(m_{\mbox{tan}} = 2x\) at a point \((x,y)\) can help us quickly find an equation of the line tangent to the graph of \(y = x^2\) at any point and answer a number of difficult-sounding questions.

Find equations of the lines tangent to \(y = x^2\) at the points \((3, 9)\) and \((p, p^2)\).

Solution

At \((3, 9)\), the slope of the tangent line is \(2x = 2(3) = 6\), and the equation of the line is \(y - 9 = 6(x - 3) \Rightarrow y = 6x - 9\).

At \((p, p^2)\), the slope of the tangent line is \(2x = 2(p) = 2p\), and the equation of the line is \(y - p^2 = 2p(x - p) \Rightarrow y = 2px - p^2\).

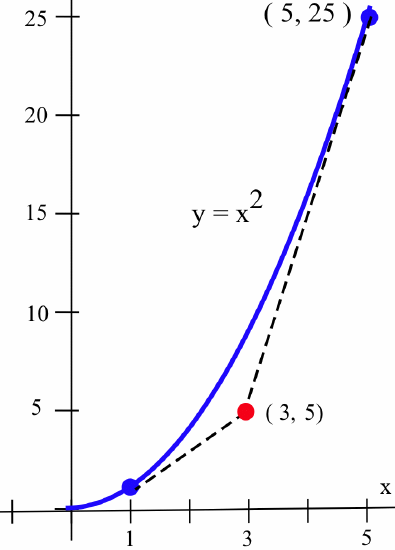

A rocket has been programmed to follow the path \(y = x^2\) in space (from left to right along the curve, as seen in the figure below), but an emergency has arisen and the crew must return to their base, which is located at coordinates \((3,5)\).

At what point on the path \(y = x^2\) should the captain turn off the engines so that the ship will coast along a path tangent to the curve to return to the base?

Solution

You might spend a few minutes trying to solve this problem without using the relation \(m_{\mbox{tan}} = 2x\), but the problem is much easier if we do use that result.

Let’s assume that the captain turns off the engine at the point \((p,q)\) on the curve \(y = x^2\) and then try to determine what values \(p\) and \(q\) must have so that the resulting tangent line to the curve will go through the point \((3,5)\). The point \((p,q)\) is on the curve \(y = x^2\), so \(q = p^2\) and the equation of the tangent line, found in Example \(\PageIndex{3}\), must then be \(y = 2px - p^2\).

To find the value of \(p\) so that the tangent line will go through the point \((3,5)\), we can substitute the values \(x = 3\) and \(y = 5\) into the equation of the tangent line and solve for \(p\): \begin{align*}y = 2px - p^2 \ \Rightarrow \ 5 = 2p(3) - p^2 \ &\Rightarrow \ p^2 - 6p + 5 = 0\\ &\Rightarrow \ (p - 1)(p - 5) = 0\end{align*} The only solutions are \(p = 1\) and \(p = 5\), so the only possible points are \((1,1)\) and \((5,25)\).

You can verify that the tangent lines to \(y = x^2\) at \((1,1)\) and \((5,25)\) both go through the point \((3,5)\). Because the ship is moving from left to right along the curve, the captain should turn off the engines at the point \((1,1)\). (Why not at \((5,25)\)?)

Verify that if the rocket engines in Example 4 are shut off at \((2,4)\), then the rocket will go through the point \((3,8)\).

- Answer

-

From Example \(\PageIndex{4}\) we know the slope of the tangent line is \(m_{\mbox{tan}} = 2x\), so the slope of the tangent line at \((2,4)\) is \(m_{\mbox{tan}} = 2x = 2(2) = 4\). The tangent line has slope \(4\) and goes through the point \((2,4)\), so an equation of the tangent line (using \(y - y_0 = m(x - x_0)\)) is \(y - 4 = 4(x - 2)\) or \(y = 4x - 4\). The point \((3,8)\) satisfies the equation \(y = 4x - 4\), so the point \((3,8)\) lies on the tangent line.

Problems

- Use the function \(f(x)\) graphed below to fill in the table and then graph \(m(x)\), the estimated slope of the tangent line to \(y=f(x)\) at the point \((x,y)\).

\(x\) \(f(x)\) \(m(x)\) \(x\) \(f(x)\) \(m(x)\) \(0.0\) \(2.5\) \(0.5\) \(3.0\) \(1.0\) \(3.5\) \(1.5\) \(4.0\) \(2.0\) - Use the function \(g(x)\) graphed below to fill in the table and then graph \(m(x)\), the estimated slope of the tangent line to \(y=g(x)\) at the point \((x,y)\).

\(x\) \(g(x)\) \(m(x)\) \(x\) \(g(x)\) \(m(x)\) \(0.0\) \(2.5\) \(0.5\) \(3.0\) \(1.0\) \(3.5\) \(1.5\) \(4.0\) \(2.0\) -

- At what values of \(x\) does the graph of \(f\) (shown below) have a horizontal tangent line?

- At what value(s) of \(x\) is the value of \(f\) the largest? Smallest?

- Sketch a graph of \(m(x)\), the slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(f\) at the point \((x,f(x))\).

- At what values of \(x\) does the graph of \(f\) (shown below) have a horizontal tangent line?

-

- At what values of \(x\) does the graph of \(g\) (shown below) have a horizontal tangent line?

- At what value(s) of \(x\) is the value of \(g\) the largest? Smallest?

- Sketch a graph of \(m(x)\), the slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(g\) at the point \((x,g(x))\).

- At what values of \(x\) does the graph of \(g\) (shown below) have a horizontal tangent line?

-

- Sketch the graph of \(f(x) = \sin(x)\) on the interval \(-3 \leq x \leq 10\).

- Sketch a graph of \(m(x)\), the slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(\sin(x)\) at the point \((x, \sin(x))\).

- Your graph in part (b) should look familiar. What function is it?

- Match the situation descriptions with the corresponding time-velocity graphs shown below.

- A car quickly leaving from a stop sign.

- A car sedately leaving from a stop sign.

- A student bouncing on a trampoline.

- A ball thrown straight up.

- A student confidently striding across campus to take a calculus test.

- An unprepared student walking across campus to take a calculus test.

Problems 7–10 assume that a rocket is following the path \(y = x^2\), from left to right.

- At what point should the engine be turned off in order to coast along the tangent line to a base at \((5,16)\)?

- At \((3,-7)\)?

- At \((1,3)\)?

- Which points in the plane can not be reached by the rocket? Why not?

In Problems 11–16, perform these steps:

- Calculate and simplify: \(\displaystyle m_{\mbox{sec}} = \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{(x+h) - (x)}\)

- Determine \(\displaystyle m_{\mbox{tan}} = \lim_{h\to 0} \, m_{\mbox{sec}}\).

- Evaluate \(m_{\mbox{tan}}\) at \(x = 2\).

- Find an equation of the line tangent to the graph of \(f\) at \((2, f(2))\).

- \(f(x) = 3x - 7\)

- \(f(x) = 2 - 7x\)

- \(f(x) = ax + b\) where \(a\) and \(b\) are constants

- \(f(x) = x^2 + 3x\)

- \(f(x) = 8 - 3x^2\)

- \(f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c\) where \(a\), \(b\) and \(c\) are constants

In Problems 17–18, use the result: \(\displaystyle f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c \ \Rightarrow \ m_{\mbox{tan}} = 2ax + b\)

- Given \(f(x) = x^2 + 2x\), at which point(s) \((p, f(p))\) does the line tangent to the graph at that point also go through the point \((3, 6)\)?

-

- If \(a \neq 0\), then what is the shape of the graph of \(y = f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c\)?

- At what value(s) of \(x\) is the line tangent to the graph of \(f(x)\) horizontal?