13.8: Laplace inverse

- Page ID

- 51238

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Up to now we have computed the inverse Laplace transform by table lookup. For example, \(\mathcal{L}^{-1} (1/(s - a)) = e^{at}\). To do this properly we should first check that the Laplace transform has an inverse.

We start with the bad news: Unfortunately this is not strictly true. There are many functions with the same Laplace transform. We list some of the ways this can happen.

- If \(f(t) = g(t)\) for \(t \ge 0\), then clearly \(F(s) = G(s)\). Since the Laplace transform only concerns \(t \ge 0\), the functions can differ completely for \(t < 0\).

- Suppose \(f(t) = e^{at}\) and

\[g(t) = \begin{cases} f(t) & \text{ for } t \ne 1 \\ 0 & \text{ for } t = 1. \end{cases} \nonumber \]

That is, \(f\) and \(g\) are the same except we arbitrarily assigned them different values at \(t = 1\). Then, since the integrals won’t notice the difference at one point, \(F(s) = G(s) = 1/(s - a)\). In this sense it is impossible to define \(\mathcal{L}^{-1} (F)\) uniquely.

The good news is that the inverse exists as long as we consider two functions that only differ on a negligible set of points the same. In particular, we can make the following claim.

Suppose \(f\) and \(g\) are continuous and \(F(s) = G(s)\) for all \(s\) with \(\text{Re} (s) > a\) for some \(a\). Then \(f(t) = g(t)\) for \(t \ge 0\).

This theorem can be stated in a way that includes piecewise continuous functions. Such a statement takes more care, which would obscure the basic point that the Laplace transform has a unique inverse up to some, for us, trivial differences.

We start with a few examples that we can compute directly.

Let

\[f(t) = e^{at}. \nonumber \]

So,

\[F(s) = \dfrac{1}{s - a}. \nonumber \]

Show

\[f(t) = \sum \text{Res} (F(s) e^{st}) \nonumber \]

\[f(t) = \dfrac{1}{2\pi i} \int_{c - i\infty}^{c + i \infty} F(s) e^{st}\ ds \nonumber \]

The sum is over all poles of \(e^{st}/(s - a)\). As usual, we only consider \(t > 0\).

Here, \(c > \text{Re} (a)\) and the integral means the path integral along the vertical line \(x = c\).

Solution

Proving Equation 13.8.4 is straightforward: It is clear that

\[\dfrac{e^{st}}{s -a} \nonumber \]

has only one pole which is at \(s = a\). Since,

\[\sum \text{Res} (\dfrac{e^{st}}{s - a}, a) = e^{at} \nonumber \]

we have proved Equation 13.8.4.

Proving Equation 13.8.5 is more involved. We should first check the convergence of the integral. In this case, \(s = c + iy\), so the integral is

\[\dfrac{1}{2\pi i} \int_{c - i \infty}^{c + i \infty} F(s) e^{st} \ ds = \dfrac{1}{2\pi i} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \dfrac{e^{(c + iy)t}}{c + iy - a} i \ dy = \dfrac{e^{ct}}{2 \pi} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \dfrac{e^{iyt}}{c + iy - a} \ dy. \nonumber \]

The (conditional) convergence of this integral follows using exactly the same argument as in the example near the end of Topic 9 on the Fourier inversion formula for \(f(t) = e^{at}\). That is, the integrand is a decaying oscillation, around 0, so its integral is also a decaying oscillation around some limiting value.

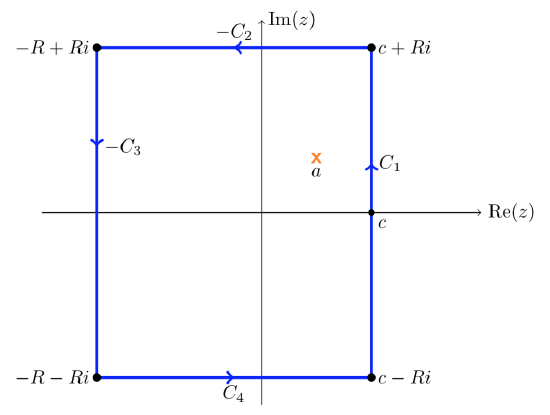

Now we use the contour shown below.

We will let \(R\) go to infinity and use the following steps to prove Equation 13.8.5.

- The residue theorem guarantees that if the curve is large enough to contain \(a\) then

\[\dfrac{1}{2\pi i} \int_{C_1 - C_2 - C_3 + C_4} \dfrac{e^{st}}{s - a}\ ds = \sum \text{Res} (\dfrac{e^{st}}{s - a}, a) = e^{at}. \nonumber \] - In a moment we will show that the integrals over \(C_2, C_3, C_4\) all go to 0 as \(R \to \infty\).

- Clearly as \(R\) goes to infinity, the integral over \(C_1\) goes to the integral in Equation 13.8.5 Putting these steps together we have

\[e^{at} = \lim_{R \to \infty} \int_{C_1 - C_2 - C_3 + C_4} \dfrac{e^{st}}{s - a} \ ds = \int_{c - i\infty}^{c + i\infty} \dfrac{e^{st}}{s - a} \ ds \nonumber \]

Except for proving the claims in step 2, this proves Equation 13.8.5.

To verify step 2 we look at one side at a time.

\(C_2\): \(C_2\) is parametrized by \(s = \gamma (u) = u + iR\), with \(-R \le u \le c\). So,

\[|\int_{C_2} \dfrac{e^{st}}{s - a} \ ds| = \int_{-R}^{c} |\dfrac{e^{(u + iR)t}}{u + iR - a}| \le \int_{-R}^{c} \dfrac{e^{ut}}{R} \ du = \dfrac{e^{ct} - e^{-Rt}}{tR}. \nonumber \]

Since \(c\) and \(t\) are fixed, it’s clear this goes to 0 as \(R\) goes to infinity.

The bottom \(C_4\) is handled in exactly the same manner as the top \(C_2\).

\(C_3\): \(C_3\) is parametrized by \(s = \gamma (u) = -R + iu\), with \(-R \le u \le R\). So,

\[|\int_{C_3} \dfrac{e^{st}}{s - a} \ ds| = \int_{-R}^{R} |\dfrac{e^{(-R + iu)t}}{-R + iu - a}| \le \int_{-R}^{R} \dfrac{e^{-Rt}}{R + a} \ du = \dfrac{e^{-Rt}}{R + a} \int_{-R}^{R} \ du = \dfrac{2\text{Re}^{-Rt}}{R+a}. \nonumber \]

Since \(a\) and \(t > 0\) are fixed, it’s clear this goes to 0 as \(R\) goes to infinity.

Repeat the previous example with \(f(t) = t\) for \(t > 0\), \(F(s) = 1/s^2\).

This is similar to the previous example. Since \(F\) decays like \(1/s^2\) we can actually allow \(t \ge 0\)

Assume \(f\) is continuous and of exponential type \(a\). Then for \(c > a\) we have

\[f(t) = \dfrac{1}{2\pi i} \int_{c - i\infty}^{c + i\infty} F(s) e^{st}\ ds. \nonumber \]

As usual, this formula holds for \(t > 0\).

- Proof

-

The proof uses the Fourier inversion formula. We will just accept this theorem for now. Example 13.8.1 above illustrates the theorem.

Suppose \(F(s)\) has a finite number of poles and decays like \(1/s\) (or faster). Define

\[f(t) = \sum \text{Res} (F(s) e^{st}, p_k), \text{ where the sum is over all the poles } p_k. \nonumber \]

Then \(\mathcal{L} (f; s) = F(s)\)

- Proof

-

Proof given in class. To be added here. The basic ideas are present in the examples above, though it requires a fairly clever choice of contours.

The integral inversion formula in Equation 13.8.13 can be viewed as writing \(f(t)\) as a ‘sum’ of exponentials. This is extremely useful. For example, for a linear system if we know how the system responds to input \(f(t) = e^{at}\) for all \(a\), then we know how it responds to any input by writing it as a ‘sum’ of exponentials.