9.10: Surface Area

- Page ID

- 490

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Another geometric question that arises naturally is: "What is the surface area of a volume?'' For example, what is the surface area of a sphere? More advanced techniques are required to approach this question in general, but we can compute the areas of some volumes generated by revolution.

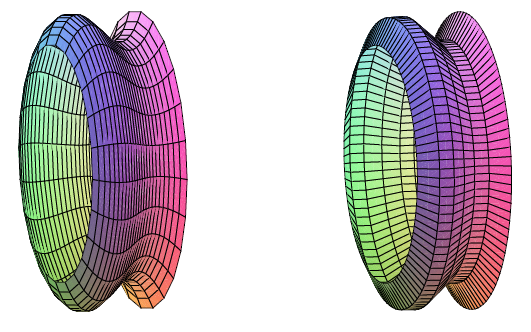

As usual, the question is: how might we approximate the surface area? For a surface obtained by rotating a curve around an axis, we can take a polygonal approximation to the curve, as in the last section, and rotate it around the same axis. This gives a surface composed of many "truncated cones;'' a truncated cone is called a frustum of a cone. Figure 9.10.1 illustrates this approximation.

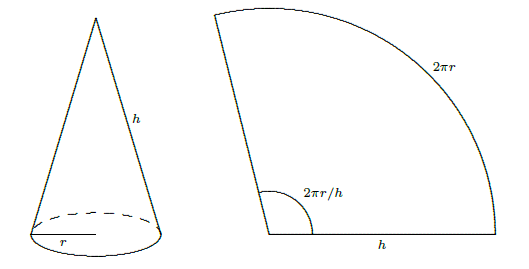

So we need to be able to compute the area of a frustum of a cone. Since the frustum can be formed by removing a small cone from the top of a larger one, we can compute the desired area if we know the surface area of a cone. Suppose a right circular cone has base radius \(r\) and slant height \(h\). If we cut the cone from the vertex to the base circle and flatten it out, we obtain a sector of a circle with radius \(h\) and arc length \(2\pi r\), as in Figure 9.10.2. The angle at the center, in radians, is then \(2\pi r/h\), and the area of the cone is equal to the area of the sector of the circle. Let \(A\) be the area of the sector; since the area of the entire circle is \(\pi h^2\), we have \[\eqalign{{A\over\pi h^2}&={2\pi r/h\over 2\pi}\cr A &= \pi r h.\cr} \nonumber \]

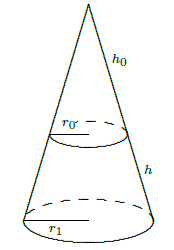

Now suppose we have a frustum of a cone with slant height \(h\) and radii \(r_0\) and \(r_1\), as in figure 9.10.3. The area of the entire cone is \(\pi r_1(h_0+h)\), and the area of the small cone is \(\pi r_0 h_0\); thus, the area of the frustum is \(\pi r_1(h_0+h)-\pi r_0 h_0=\pi((r_1-r_0)h_0+r_1h)\). By similar triangles,

\[{h_0\over r_0}={h_0+h\over r_1}. \nonumber \]

With a bit of algebra this becomes \((r_1-r_0)h_0= r_0h\); substitution into the area gives

\[\pi((r_1-r_0)h_0+r_1h)=\pi(r_0h+r_1h)=\pi h(r_0+r_1)=2\pi {r_0+r_1\over2} h = 2\pi r h. \nonumber \]

The final form is particularly easy to remember, with \(r\) equal to the average of \(r_0\) and \(r_1\), as it is also the formula for the area of a cylinder. (Think of a cylinder of radius \(r\) and height \(h\) as the frustum of a cone of infinite height.)

Now we are ready to approximate the area of a surface of revolution. On one subinterval, the situation is as shown in Figure 9.10.4. When the line joining two points on the curve is rotated around the \(x\)-axis, it forms a frustum of a cone. The area is

\[ 2\pi r h= 2\pi {f(x_i)+f(x_{i+1})\over2} \sqrt{1+(f'(t_i))^2}\,\Delta x. \nonumber \]

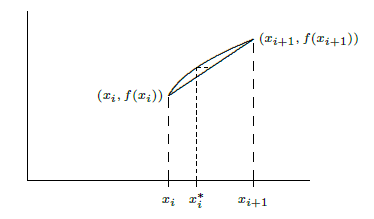

Here \(\sqrt{1+(f'(t_i))^2}\,\Delta x\) is the length of the line segment, as we found in the previous section. Assuming \(f\) is a continuous function, there must be some \(x_i^*\) in \( [x_i,x_{i+1}]\) such that \((f(x_i)+f(x_{i+1}))/2 = f(x_i^*)\), so the approximation for the surface area is \[\sum_{i=0}^{n-1} 2\pi f(x_i^*)\sqrt{1+(f'(t_i))^2}\,\Delta x. \nonumber \] This is not quite the sort of sum we have seen before, as it contains two different values in the interval \([x_i,x_{i+1}]\), namely \(x_i^*\) and \(t_i\). Nevertheless, using more advanced techniques than we have available here, it turns out that

\[\lim_{n\to\infty} \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} 2\pi f(x_i^*)\sqrt{1+(f'(t_i))^2}\,\Delta x= \int_a^b 2\pi f(x)\sqrt{1+(f'(x))^2}\,dx \nonumber \]

is the surface area we seek. (Roughly speaking, this is because while \(x_i^*\) and \(t_i\) are distinct values in \([x_i,x_{i+1}]\), they get closer and closer to each other as the length of the interval shrinks.)