9.5: Alternating Series

- Page ID

- 2566

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Use the alternating series test to test an alternating series for convergence.

- Estimate the sum of an alternating series.

- Explain the meaning of absolute convergence and conditional convergence.

So far in this chapter, we have primarily discussed series with positive terms. In this section we introduce alternating series—those series whose terms alternate in sign. We will show in a later chapter that these series often arise when studying power series. After defining alternating series, we introduce the alternating series test to determine whether such a series converges.

The Alternating Series Test

A series whose terms alternate between positive and negative values is an alternating series. For example, the series

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞ \left(−\dfrac{1}{2} \right)^n=−\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{4}−\dfrac{1}{8}+\dfrac{1}{16}− \ldots \label{eq1} \]

and

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞\dfrac{(−1)^{n+1}}{n}=1−\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{3}−\dfrac{1}{4}+\ldots \label{eq2} \]

are both alternating series.

Any series whose terms alternate between positive and negative values is called an alternating series. An alternating series can be written in the form

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞(−1)^{n+1}b_n=b_1−b_2+b_3−b_4+ \ldots \label{eq3} \]

or

\[\sum_{n−1}^∞(−1)^nb_n=−b_1+b_2−b_3+b_4−\ldots \label{eq4} \]

Where \( b_n≥0\) for all positive integers \(n\).

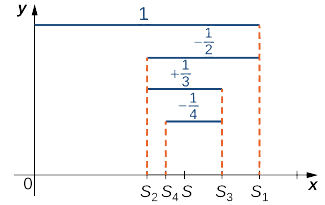

Series (1), shown in Equation \ref{eq1}, is a geometric series. Since \( |r|=|−1/2|<1,\) the series converges. Series (2), shown in Equation \ref{eq2}, is called the alternating harmonic series. We will show that whereas the harmonic series diverges, the alternating harmonic series converges. To prove this, we look at the sequence of partial sums \( \{S_k\}\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Consider the odd terms \( S_{2k+1}\) for \( k≥0\). Since \( 1/(2k+1)<1/2k,\)

\[S_{2k+1}=S_{2k−1}−\dfrac{1}{2k}+\dfrac{1}{2k+1}<S_{2k−1}. \nonumber \]

Therefore, \( \{S_{2k+1}\}\) is a decreasing sequence. Also,

\[S_{2k+1}=\left(1−\dfrac{1}{2}\right)+\left(\dfrac{1}{3}−\dfrac{1}{4}\right)+ \ldots + \left(\dfrac{1}{2k−1}−\dfrac{1}{2k}\right)+\dfrac{1}{2k+1}>0. \nonumber \]

Therefore, \( \{S_{2k+1}\}\) is bounded below. Since \( \{S_{2k+1}\}\) is a decreasing sequence that is bounded below, by the Monotone Convergence Theorem, \( \{S_{2k+1}\}\) converges. Similarly, the even terms \( \{S_{2k}\}\) form an increasing sequence that is bounded above because

\[S_{2k}=S_{2k−2}+\dfrac{1}{2k−1}−\dfrac{1}{2k}>S_{2k−2} \nonumber \]

and

\[S_{2k}=1+ \left(−\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{3}\right)+\ldots + \left(−\dfrac{1}{2k−2}+\dfrac{1}{2k−1}\right)−\dfrac{1}{2k}<1. \nonumber \]

Therefore, by the Monotone Convergence Theorem, the sequence \( \{S_{2k}\}\) also converges. Since

\[S_{2k+1}=S_{2k}+\dfrac{1}{2k+1}, \nonumber \]

we know that

\[\lim_{k→∞}S_{2k+1}=\lim_{k→∞}S_{2k}+\lim_{k→∞}\dfrac{1}{2k+1}. \nonumber \]

Letting \(\displaystyle S=\lim_{k→∞}S_{2k+1}\) and using the fact that \( 1/(2k+1)→0,\) we conclude that \(\displaystyle \lim_{k→∞}S_{2k}=S\). Since the odd terms and the even terms in the sequence of partial sums converge to the same limit \( S\), it can be shown that the sequence of partial sums converges to \( S\), and therefore the alternating harmonic series converges to \( S\).

It can also be shown that \( S=\ln 2,\) and we can write

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞\dfrac{(−1)^{n+1}}{n}=1−\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{3}−\dfrac{1}{4}+a\ldots=\ln (2). \nonumber \]

□

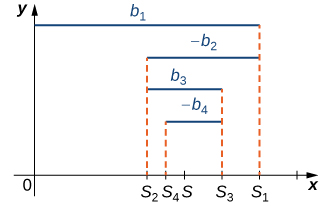

More generally, any alternating series of form (3) (Equation \ref{eq3}) or (4) (Equation \ref{eq4}) converges as long as \( b_1≥b_2≥b_3≥⋯\) and \( b_n→0\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). The proof is similar to the proof for the alternating harmonic series.

An alternating series of the form

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞(−1)^{n+1}b_n \nonumber \] or \[\sum_{n=1}^∞(−1)^nb_n \nonumber \]

converges if

- \( 0≤b_{n+1}≤b_n\) for all \( n≥1\) and

- \(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}b_n=0.\)

This is known as the alternating series test.

We remark that this theorem is true more generally as long as there exists some integer \( N\) such that \( 0≤b_{n+1}≤b_n\) for all \( n≥N.\)

For each of the following alternating series, determine whether the series converges or diverges.

- \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{(−1)^{n+1}}{n^2}\)

- \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}(−1)^{n+1}\frac{n}{n+1}\)

Solution

a. Since \( \dfrac{1}{(n+1)^2}<\dfrac{1}{n^2}\) and \( \dfrac{1}{n^2}→0,\) the series converges.

b. Since \( n/(n+1)↛0\) as \( n→∞\), we cannot apply the alternating series test. Instead, we use the nth term test for divergence. Since \(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}\dfrac{n}{n+1}=1≠0,\) the series diverges.

Determine whether the series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}(−1)^{n+1}\frac{n}{2^n}\) converges or diverges.

- Hint

-

Is \( \left\{\frac{n}{2^n}\right\}\) decreasing? What is \(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}\frac{n}{2^n}\)?

- Answer

-

The series converges.

Remainder of an Alternating Series

It is difficult to explicitly calculate the sum of most alternating series, so typically the sum is approximated by using a partial sum. When doing so, we are interested in the amount of error in our approximation. Consider an alternating series

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞(−1)^{n+1}b_n \nonumber \]

satisfying the hypotheses of the alternating series test. Let \( S\) denote the sum of this series and \( {S_k}\) be the corresponding sequence of partial sums. From Figure \( \PageIndex{2}\), we see that for any integer \( N≥1\), the remainder \( R_N\) satisfies

\[|R_N|=|S−S_N|≤|S_{N+1}−S_N|=b_{n+1}. \nonumber \]

Consider an alternating series of the form

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞(−1)^{n+1}b_n \nonumber \] or \[\sum_{n=1}^∞(−1)^nb_n \nonumber \]

that satisfies the hypotheses of the alternating series test. Let \( S\) denote the sum of the series and \( S_N\) denote the \(N^{\text{th}}\) partial sum. For any integer \( N≥1\), the remainder \( R_N=S−S_N\) satisfies

\[|R_N|≤b_{N+1}. \nonumber \]

In other words, if the conditions of the alternating series test apply, then the error in approximating the infinite series by the \(N^{\text{th}}\) partial sum \( S_N\) is in magnitude at most the size of the next term \( b_{N+1}\).

Consider the alternating series

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞\dfrac{(−1)^{n+1}}{n^2}. \nonumber \]

Use the remainder estimate to determine a bound on the error \( R_{10}\) if we approximate the sum of the series by the partial sum \( S_{10}\).

Solution

From the theorem stated above, \[ |R_{10}|≤b_{11}=\dfrac{1}{11^2}≈0.008265. \nonumber \]

Find a bound for \( R_{20}\) when approximating \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{(−1)^{n+1}}{n}\) by \( S_{20}\).

- Hint

-

\( |R_{20}|≤b_{21}\)

- Answer

-

\( 0.04762\)

Absolute and Conditional Convergence

Consider a series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞a_n\) and the related series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞|a_n|\). Here we discuss possibilities for the relationship between the convergence of these two series. For example, consider the alternating harmonic series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{(−1)^{n+1}}{n}\). The series whose terms are the absolute value of these terms is the harmonic series, since \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\left|\frac{(−1)^{n+1}}{n}\right|=\sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{1}{n}.\) Since the alternating harmonic series converges, but the harmonic series diverges, we say the alternating harmonic series exhibits conditional convergence.

By comparison, consider the series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{(−1)^{n+1}}{n^2}.\) The series whose terms are the absolute values of the terms of this series is the series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{1}{n^2}.\) Since both of these series converge, we say the series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\frac{(−1)^{n+1}}{n^2}\) exhibits absolute convergence.

A series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) exhibits absolute convergence if \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}|a_n|\) converges. A series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) exhibits conditional convergence if \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) converges but \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}|a_n|\) diverges.

As shown by the alternating harmonic series, a series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) may converge, but \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}|a_n|\) may diverge. In the following theorem, however, we show that if \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}|a_n|\) converges, then \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) converges.

If \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}|a_n|\) converges, then \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) converges.

Suppose that \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞|a_n|\) converges. We show this by using the fact that \( a_n=|a_n|\) or \( a_n=−|a_n|\) and therefore \( |a_n|+a_n=2|a_n|\) or \( |a_n|+a_n=0\). Therefore, \( 0≤|a_n|+a_n≤2|a_n|\). Consequently, by the comparison test, since \( 2\sum^∞_{n=1}|a_n|\) converges, the series

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞(|a_n|+a_n) \nonumber \]

converges. By using the algebraic properties for convergent series, we conclude that

\[\sum_{n=1}^∞a_n=\sum_{n=1}^∞(|a_n|+a_n)−\sum_{n=1}^∞|a_n| \nonumber \]

converges.

□

For each of the following series, determine whether the series converges absolutely, converges conditionally, or diverges.

- \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{(−1)^{n+1}}{3n+1}\)

- \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{\cos(n)}{n^2}\)

Solution

a. We can see that

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\left|\dfrac{(−1)^{n+1}}{3n+1}\right|=\sum_{n=1}^∞\dfrac{1}{3n+1}\)

diverges by using the limit comparison test with the harmonic series. In fact,

\(\displaystyle \lim_{n→∞}\dfrac{1/(3n+1)}{1/n}=\dfrac{1}{3}\).

Therefore, the series does not converge absolutely. However, since

\( \dfrac{1}{3(n+1)+1}<\dfrac{1}{3n+1}\) and \( \dfrac{1}{3n+1}→0\),

the series converges. We can conclude that \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{(−1)^{n+1}}{3n+1}\) converges conditionally.

b. Noting that \( |\cos n|≤1,\) to determine whether the series converges absolutely, compare

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞\left|\dfrac{\cos n}{n^2}\right|\)

with the series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{1}{n^2}\). Since \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{1}{n^2}\) converges, by the comparison test, \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\left|\frac{\cos n}{n^2}\right|\) converges, and therefore \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{\cos n}{n^2}\) converges absolutely.

Determine whether the series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}(−1)^{n+1}\frac{n}{2n^3+1}\) converges absolutely, converges conditionally, or diverges.

- Hint

-

Check for absolute convergence first.

- Answer

-

The series converges absolutely.

To see the difference between absolute and conditional convergence, look at what happens when we rearrange the terms of the alternating harmonic series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}(−1)^{n+1}\frac{1}{n}\). We show that we can rearrange the terms so that the new series diverges. Certainly if we rearrange the terms of a finite sum, the sum does not change. When we work with an infinite sum, however, interesting things can happen.

Begin by adding enough of the positive terms to produce a sum that is larger than some real number \( M=10\) For example, let \( M=10,\) and find an integer \( k\) such that

\[1+\dfrac{1}{3}+\dfrac{1}{5}+⋯+\dfrac{1}{2k−1}>10 \nonumber \]

(We can do this because the series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}\frac{1}{2n−1}\) diverges to infinity.) Then subtract \( 1/2\). Then add more positive terms until the sum reaches 100. That is, find another integer \( j>k\) such that

\[(1+\dfrac{1}{3}+⋯+\dfrac{1}{2k−1}−\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{2k+1}+ \ldots +\dfrac{1}{2j+1}>100. \nonumber \]

Then subtract \( 1/4.\) Continuing in this way, we have found a way of rearranging the terms in the alternating harmonic series so that the sequence of partial sums for the rearranged series is unbounded and therefore diverges.

The terms in the alternating harmonic series can also be rearranged so that the new series converges to a different value. In Example, we show how to rearrange the terms to create a new series that converges to \( 3\ln(2)/2\). We point out that the alternating harmonic series can be rearranged to create a series that converges to any real number \( r\); however, the proof of that fact is beyond the scope of this text.

In general, any series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) that converges conditionally can be rearranged so that the new series diverges or converges to a different real number. A series that converges absolutely does not have this property. For any series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) that converges absolutely, the value of \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) is the same for any rearrangement of the terms. This result is known as the Riemann Rearrangement Theorem, which is beyond the scope of this book.

Use the fact that

\[ 1−\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{3}−\dfrac{1}{4}+\dfrac{1}{5}−⋯=\ln 2 \nonumber \]

to rearrange the terms in the alternating harmonic series so the sum of the rearranged series is \( 3\ln (2)/2.\)

Solution

Let

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞a_n=1−\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{3}−\dfrac{1}{4}+\dfrac{1}{5}−\dfrac{1}{6}+\dfrac{1}{7}−\dfrac{1}{8}+⋯. \nonumber \]

Since \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞a_n=\ln (2)\), by the algebraic properties of convergent series,

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞\dfrac{1}{2}a_n=\dfrac{1}{2}−\dfrac{1}{4}+\dfrac{1}{6}−\dfrac{1}{8}+⋯=\dfrac{1}{2}\sum_{n=1}^∞a_n=\dfrac{\ln 2}{2}. \nonumber \]

Now introduce the series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞b_n\) such that for all \( n≥1, b_{2n−1}=0\) and \( b_{2n}=a_n/2.\) Then

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞b_n=0+\dfrac{1}{2}+0−\dfrac{1}{4}+0+\dfrac{1}{6}+0−\dfrac{1}{8}+⋯=\dfrac{\ln 2}{2}. \nonumber \]

Then using the algebraic limit properties of convergent series, since \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞a_n\) and \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞b_n\) converge, the series \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞(a_n+b_n)\) converges and

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞(a_n+b_n)=\sum_{n=1}^∞a_n+\sum_{n=1}^∞b_n=\ln 2+\dfrac{\ln 2}{2}=\dfrac{3\ln 2}{2}. \nonumber \]

Now adding the corresponding terms, \( a_n\) and \( b_n\), we see that

\[ \sum_{n=1}^∞(a_n+b_n)=(1+0)+\left(−\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{2}\right)+\left(\dfrac{1}{3}+0\right)+\left(−\dfrac{1}{4}−14\right)+\left(\dfrac{1}{5}+0\right)+\left(−\dfrac{1}{6}+\dfrac{1}{6}\right)+\left(\dfrac{1}{7}+0\right)+\left(\dfrac{1}{8}−\dfrac{1}{8}\right)+⋯=1+\dfrac{1}{3}−\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{5}+\dfrac{1}{7}−\dfrac{1}{4}+⋯. \nonumber \]

We notice that the series on the right side of the equal sign is a rearrangement of the alternating harmonic series. Since \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞(a_n+b_n)=3\ln (2)/2,\) we conclude that

\[ 1+\dfrac{1}{3}−\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{1}{5}+\dfrac{1}{7}−\dfrac{1}{4}+⋯=\dfrac{3\ln (2)}{2}. \nonumber \]

Therefore, we have found a rearrangement of the alternating harmonic series having the desired property.

Key Concepts

- For an alternating series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}(−1)^{n+1}b_n,\) if \( b_{k+1}≤b_k\) for all \( k\) and \( b_k→0\) as \( k→∞,\) the alternating series converges.

- If \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}|a_n|\) converges, then \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) converges.

Key Equations

- Alternating series

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞(−1)^{n+1}b_n=b_1−b_2+b_3−b_4+⋯\) or

\(\displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^∞(−1)^nb_n=−b_1+b_2−b_3+b_4−⋯\)

Glossary

- absolute convergence

- if the series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}|a_n|\) converges, the series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) is said to converge absolutely

- alternating series

- a series of the form \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}(−1)^{n+1}b_n\) or \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}(−1)^nb_n\), where \( b_n≥0\), is called an alternating series

- alternating series test

- for an alternating series of either form, if \( b_{n+1}≤b_n\) for all integers \( n≥1\) and \( b_n→0\), then an alternating series converges

- conditional convergence

- if the series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) converges, but the series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}|a_n|\) diverges, the series \(\displaystyle \sum^∞_{n=1}a_n\) is said to converge conditionally