13.2: Calculus of Vector-Valued Functions

- Page ID

- 2595

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Write an expression for the derivative of a vector-valued function.

- Find the tangent vector at a point for a given position vector.

- Find the unit tangent vector at a point for a given position vector and explain its significance.

- Calculate the definite integral of a vector-valued function.

To study the calculus of vector-valued functions, we follow a similar path to the one we took in studying real-valued functions. First, we define the derivative, then we examine applications of the derivative, then we move on to defining integrals. However, we will find some interesting new ideas along the way as a result of the vector nature of these functions and the properties of space curves.

Derivatives of Vector-Valued Functions

Now that we have seen what a vector-valued function is and how to take its limit, the next step is to learn how to differentiate a vector-valued function. The definition of the derivative of a vector-valued function is nearly identical to the definition of a real-valued function of one variable. However, because the range of a vector-valued function consists of vectors, the same is true for the range of the derivative of a vector-valued function.

The derivative of a vector-valued function \(\vecs{r}(t)\) is

\[\vecs{r}′(t) = \lim \limits_{\Delta t \to 0} \dfrac{\vecs{r}(t+\Delta t)−\vecs{r}(t)}{ \Delta t} \label{eq1} \]

provided the limit exists. If \(\vecs{r}'(t)\) exists, then \(\vecs{r}(t)\) is differentiable at \(t\). If \(\vecs{r}′(t)\) exists for all \(t\) in an open interval \((a,b)\) then \(\vecs{r}(t)\) is differentiable over the interval \((a,b)\). For the function to be differentiable over the closed interval \([a,b]\), the following two limits must exist as well:

\[\vecs{r}′(a) = \lim \limits_{\Delta t \to 0^+} \dfrac{\vecs{r}(a+\Delta t)−\vecs{r}(a)}{ \Delta t} \nonumber \]

and

\[\vecs{r}′(b) = \lim \limits_{\Delta t \to 0^-} \dfrac{\vecs{r}(b+\Delta t)−\vecs{r}(b)}{ \Delta t} \nonumber \]

Many of the rules for calculating derivatives of real-valued functions can be applied to calculating the derivatives of vector-valued functions as well. Recall that the derivative of a real-valued function can be interpreted as the slope of a tangent line or the instantaneous rate of change of the function. The derivative of a vector-valued function can be understood to be an instantaneous rate of change as well; for example, when the function represents the position of an object at a given point in time, the derivative represents its velocity at that same point in time.

We now demonstrate taking the derivative of a vector-valued function.

Use the definition to calculate the derivative of the function

\[\vecs{r}(t)=(3t+4) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(t^2−4t+3) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} .\nonumber \]

Solution

Let’s use Equation \ref{eq1}:

\[\begin{align*} \vecs{r}′(t) &= \lim \limits_{\Delta t \to 0} \dfrac{\vecs{r}(t+Δt)− \vecs{r} (t)}{Δt} \\[4pt]

&= \lim \limits_{\Delta t \to 0} \dfrac{[(3(t+Δt)+4)\,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+((t+Δt)^2−4(t+Δt)+3)\,\hat{\mathbf{j}}]−[(3t+4) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(t^2−4t+3) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}]}{Δt} \\[4pt]

&= \lim \limits_{\Delta t \to 0} \dfrac{(3t+3Δt+4)\,\hat{\mathbf{i}}−(3t+4) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(t^2+2tΔt+(Δt)^2−4t−4Δt+3) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}−(t^2−4t+3)\,\hat{\mathbf{j}}}{Δt} \\[4pt]

&= \lim \limits_{\Delta t \to 0} \dfrac{(3Δt)\,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(2tΔt+(Δt)^2−4Δt)\,\hat{\mathbf{j}}}{Δt} \\[4pt]

&= \lim \limits_{\Delta t \to 0} (3 \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(2t+Δt−4)\,\hat{\mathbf{j}}) \\[4pt]

&=3 \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(2t−4) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} \end{align*} \nonumber \]

Use the definition to calculate the derivative of the function \(\vecs{r}(t)=(2t^2+3) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(5t−6) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}\).

- Hint

-

Use Equation \ref{eq1}.

- Answer

-

\[\vecs{r}′(t)=4t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+5 \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} \nonumber \]

Notice that in the calculations in Example \(\PageIndex{1}\), we could also obtain the answer by first calculating the derivative of each component function, then putting these derivatives back into the vector-valued function. This is always true for calculating the derivative of a vector-valued function, whether it is in two or three dimensions. We state this in the following theorem. The proof of this theorem follows directly from the definitions of the limit of a vector-valued function and the derivative of a vector-valued function.

Let \(f\), \(g\), and \(h\) be differentiable functions of \(t\).

- If \(\vecs{r}(t)=f(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}\) then \[\vecs{r}′(t)=f′(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g′(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}. \nonumber \]

- If \(\vecs{r}(t)=f(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} + h(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\) then \[\vecs{r}′(t)=f′(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g′(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} + h′(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}. \nonumber \]

Use Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\) to calculate the derivative of each of the following functions.

- \(\vecs{r}(t)=(6t+8) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(4t^2+2t−3) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}\)

- \(\vecs{r}(t)=3 \cos t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+4 \sin t \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}\)

- \(\vecs{r}(t)=e^t \sin t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+e^t \cos t \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}−e^{2t} \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\)

Solution

We use Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\) and what we know about differentiating functions of one variable.

- The first component of \[\vecs r(t)=(6t+8) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(4t^2+2t−3) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} \nonumber \] is \(f(t)=6t+8\). The second component is \(g(t)=4t^2+2t−3\). We have \(f′(t)=6\) and \(g′(t)=8t+2\), so the Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\) gives \(\vecs r′(t)=6 \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(8t+2)\,\mathbf{\hat{j}}\).

- The first component is \(f(t)=3 \cos t\) and the second component is \(g(t)=4 \sin t\). We have \(f′(t)=−3 \sin t\) and \(g′(t)=4 \cos t\), so we obtain \(\vecs r′(t)=−3 \sin t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+4 \cos t \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}\).

- The first component of \(\vecs r(t)=e^t \sin t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+e^t \cos t \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}−e^{2t} \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\) is \(f(t)=e^t \sin t\), the second component is \(g(t)=e^t \cos t\), and the third component is \(h(t)=−e^{2t}\). We have \(f′(t)=e^t(\sin t+\cos t)\), \(g′(t)=e^t (\cos t−\sin t)\), and \(h′(t)=−2e^{2t}\), so the theorem gives \(\vecs r′(t)=e^t(\sin t+\cos t)\,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+e^t(\cos t−\sin t)\,\mathbf{\hat{j}}−2e^{2t} \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\).

Calculate the derivative of the function

\[\vecs{r}(t)=(t \ln t)\,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(5e^t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+(\cos t−\sin t) \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}. \nonumber \]

- Hint

-

Identify the component functions and use Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\).

- Answer

-

\[\vecs{r}′(t)=(1+ \ln t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+5e^t \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}−(\sin t+\cos t)\,\mathbf{\hat{k}} \nonumber \]

We can extend to vector-valued functions the properties of the derivative that we presented previously. In particular, the constant multiple rule, the sum and difference rules, the product rule, and the chain rule all extend to vector-valued functions. However, in the case of the product rule, there are actually three extensions:

- for a real-valued function multiplied by a vector-valued function,

- for the dot product of two vector-valued functions, and

- for the cross product of two vector-valued functions.

Let \(\vecs{r}\) and \(\vecs{u}\) be differentiable vector-valued functions of \(t\), let \(f\) be a differentiable real-valued function of \(t\), and let \(c\) be a scalar.

\[\begin{array}{lrcll} \mathrm{i.} & \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[c\vecs r(t)] & = & c\vecs r′(t) & \text{Scalar multiple} \nonumber\\ \mathrm{ii.} & \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs r(t)±\vecs u(t)] & = & \vecs r′(t)±\vecs u′(t) & \text{Sum and difference} \nonumber\\ \mathrm{iii.} & \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[f(t)\vecs u(t)] & = & f′(t)\vecs u(t)+f(t)\vecs u′(t) & \text{Scalar product} \nonumber\\ \mathrm{iv.} & \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs r(t)⋅\vecs u(t)] & = & \vecs r′(t)⋅\vecs u(t)+\vecs r(t)⋅\vecs u′(t) & \text{Dot product} \nonumber\\ \mathrm{v.} & \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs r(t)×\vecs u(t)] & = & \vecs r′(t)×\vecs u(t)+\vecs r(t)×\vecs u′(t) & \text{Cross product} \nonumber\\ \mathrm{vi.} & \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs r(f(t))] & = & \vecs r′(f(t))⋅f′(t) & \text{Chain rule} \nonumber\\ \mathrm{vii.} & \text{If} \; \vecs r(t)·\vecs r(t) & = & c, \text{then} \; \vecs r(t)⋅\vecs r′(t) \; =0 \; . & \mathrm{} \nonumber \end{array} \nonumber \]

The proofs of the first two properties follow directly from the definition of the derivative of a vector-valued function. The third property can be derived from the first two properties, along with the product rule. Let \(\vecs u(t)=g(t)\,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+h(t)\,\mathbf{\hat{j}}\). Then

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[f(t)\vecs u(t)] &=\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[f(t)(g(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+h(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}})] \\[4pt]

&=\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[f(t)g(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+f(t)h(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}] \\[4pt]

&=\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[f(t)g(t)] \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[f(t)h(t)] \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} \\[4pt]

&=(f′(t)g(t)+f(t)g′(t)) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(f′(t)h(t)+f(t)h′(t)) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} \\[4pt]

&=f′(t)\vecs u(t)+f(t)\vecs u′(t). \end{align*} \nonumber \]

To prove property iv. let \(\vecs r(t)=f_1(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g_1(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}\) and \(\vecs u(t)=f_2(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g_2(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}\). Then

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs r(t)⋅\vecs u(t)] &=\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[f_1(t)f_2(t)+g_1(t)g_2(t)] \\[4pt]

&=f_1′(t)f_2(t)+f_1(t)f_2′(t)+g_1′(t)g_2(t)+g_1(t)g_2′(t)=f_1′(t)f_2(t)+g_1′(t)g_2(t)+f_1(t)f_2′(t)+g_1(t)g_2′(t) \\[4pt]

&=(f_1′ \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g_1′ \,\mathbf{\hat{j}})⋅(f_2 \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g_2 \,\mathbf{\hat{j}})+(f_1 \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g_1 \,\mathbf{\hat{j}})⋅(f_2′ \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g_2′ \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}) \\[4pt]

&=\vecs r′(t)⋅\vecs u(t)+\vecs r(t)⋅\vecs u′(t). \end{align*} \nonumber \]

The proof of property v. is similar to that of property iv. Property vi. can be proved using the chain rule. Last, property vii. follows from property iv:

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs r(t)·\vecs r(t)] &=\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[c] \\[4pt]

\vecs r′(t)·\vecs r(t)+\vecs r(t)·\vecs r′(t) &= 0 \\[4pt]

2\vecs r(t)·\vecs r′(t) &= 0 \\[4pt]

\vecs r(t)·\vecs r′(t) &= 0 \end{align*} \nonumber \]

Now for some examples using these properties.

Given the vector-valued functions

\[\vecs{r}(t)=(6t+8)\,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(4t^2+2t−3)\,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+5t \,\mathbf{\hat{k}} \nonumber \]

and

\[\vecs{u}(t)=(t^2−3)\,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(2t+4)\,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+(t^3−3t)\,\mathbf{\hat{k}}, \nonumber \]

calculate each of the following derivatives using the properties of the derivative of vector-valued functions.

- \(\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs{r}(t)⋅ \vecs{u}(t)]\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[ \vecs{u} (t) \times \vecs{u}′(t)]\)

Solution

We have \(\vecs{r}′(t)=6 \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(8t+2) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+5 \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\) and \(\vecs{u}′(t)=2t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+2 \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+(3t^2−3) \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\). Therefore, according to property iv:

- \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs r(t)⋅\vecs u(t)] &= \vecs r′(t)⋅\vecs u(t)+\vecs r(t)⋅\vecs u′(t) \\[4pt]

&= (6 \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(8t+2) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+5 \,\mathbf{\hat{k}})⋅((t^2−3) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(2t+4) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+(t^3−3t) \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}) \\[4pt]

& \; +((6t+8) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(4t^2+2t−3) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+5t \,\mathbf{\hat{k}})⋅(2t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+2 \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+(3t^2−3)\,\mathbf{\hat{k}}) \\[4pt]

&= 6(t^2−3)+(8t+2)(2t+4)+5(t^3−3t) \\[4pt]

& \; +2t(6t+8)+2(4t^2+2t−3)+5t(3t^2−3) \\[4pt]

&= 20t^3+42t^2+26t−16. \end{align*}\] - First, we need to adapt property v for this problem:

\[\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[ \vecs{u}(t) \times \vecs{u}′(t)]=\vecs{u}′(t)\times \vecs{u}′(t)+ \vecs{u}(t) \times \vecs{u}′′(t). \nonumber \]

Recall that the cross product of any vector with itself is zero. Furthermore,\(\vecs u′′(t)\) represents the second derivative of \(\vecs u(t):\)

\[\vecs u′′(t)=\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs u′(t)]=\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[2t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+2 \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+(3t^2−3) \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}]=2 \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+6t \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}. \nonumber \]

Therefore,

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs u(t) \times \vecs u′(t)] &=0+((t^2−3)\,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(2t+4)\,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+(t^3−3t)\,\hat{\mathbf{k}})\times (2 \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+6t \,\hat{\mathbf{k}}) \\[4pt]

&= \begin{vmatrix} \,\hat{\mathbf{i}} & \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} & \,\hat{\mathbf{k}} \\ t^2-3 & 2t+4 & t^3 -3t \\ 2 & 0 & 6t \end{vmatrix} \\[4pt]

& =6t(2t+4) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}−(6t(t^2−3)−2(t^3−3t)) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}−2(2t+4) \,\hat{\mathbf{k}} \\[4pt]

& =(12t^2+24t) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(12t−4t^3) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}−(4t+8)\,\hat{\mathbf{k}}. \end{align*}\]

Calculate \(\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs{r}(t)⋅ \vecs{r}′(t)]\) and \( \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs{u}(t) \times \vecs{r}(t)]\) for the vector-valued functions:

- \(\vecs{r}(t)=\cos t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+ \sin t \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}−e^{2t} \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\)

- \(\vecs{u}(t)=t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+ \sin t \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+ \cos t \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\),

- Hint

-

Follow the same steps as in Example \(\PageIndex{3}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{d}{\,dt}[\vecs{r}(t)⋅ \vecs{r}′(t)]=8e^{4t}\)

\( \dfrac{d}{\,dt}[ \vecs{u}(t) \times \vecs{r}(t)] =−(e^{2t}(\cos t+2 \sin t)+ \cos 2t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(e^{2t}(2t+1)− \sin 2t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+(t \cos t+ \sin t− \cos 2t) \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\)

Tangent Vectors and Unit Tangent Vectors

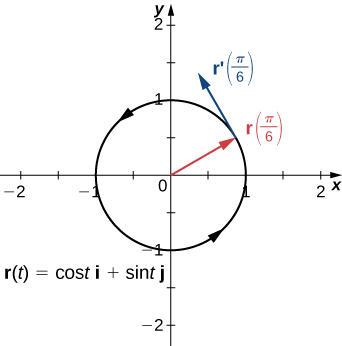

Recall that the derivative at a point can be interpreted as the slope of the tangent line to the graph at that point. In the case of a vector-valued function, the derivative provides a tangent vector to the curve represented by the function. Consider the vector-valued function

\[\vecs{r}(t)=\cos t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}} + \sin t \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} \label{eq10} \]

The derivative of this function is

\[\vecs{r}′(t)=−\sin t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}} + \cos t \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} \nonumber \]

If we substitute the value \(t=π/6\) into both functions we get

\[\vecs{r} \left(\dfrac{π}{6}\right)=\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+\dfrac{1}{2}\,\mathbf{\hat{j}} \nonumber \]

and

\[ \vecs{r}′ \left(\dfrac{π}{6} \right)=−\dfrac{1}{2}\,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\,\mathbf{\hat{j}}. \nonumber \]

The graph of this function appears in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), along with the vectors \(\vecs{r}\left(\dfrac{π}{6}\right)\) and \(\vecs{r}' \left(\dfrac{π}{6}\right)\).

Notice that the vector \(\vecs{r}′\left(\dfrac{π}{6}\right)\) is tangent to the circle at the point corresponding to \(t=\dfrac{π}{6}\). This is an example of a tangent vector to the plane curve defined by Equation \ref{eq10}.

Let \(C\) be a curve defined by a vector-valued function \(\vecs{r}\), and assume that \(\vecs{r}′(t)\) exists when \(\mathrm{t=t_0}\) A tangent vector \(\vecs{r}\) at \(t=t_0\) is any vector such that, when the tail of the vector is placed at point \(\vecs r(t_0)\) on the graph, vector \(\vecs{r}\) is tangent to curve \(C\). Vector \(\vecs{r}′(t_0)\) is an example of a tangent vector at point \(t=t_0\). Furthermore, assume that \(\vecs{r}′(t)≠0\). The principal unit tangent vector at \(t\) is defined to be

\[\vecs{T}(t)=\dfrac{ \vecs{r}′(t)}{‖\vecs{r}′(t)‖}, \nonumber \]

provided \(‖\vecs{r}′(t)‖≠0\).

The unit tangent vector is exactly what it sounds like: a unit vector that is tangent to the curve. To calculate a unit tangent vector, first find the derivative \(\vecs{r}′(t)\). Second, calculate the magnitude of the derivative. The third step is to divide the derivative by its magnitude.

Find the unit tangent vector for each of the following vector-valued functions:

- \(\vecs{r}(t)=\cos t \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+\sin t \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}\)

- \(\vecs{u}(t)=(3t^2+2t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(2−4t^3)\,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+(6t+5)\,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\)

Solution

- \(\begin{array}{lrcl} \text{First step:} & \vecs r′(t) & = & − \sin t \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \cos t \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} \\ \text{Second step:} & ‖\vecs r′(t)‖ & = & \sqrt{(− \sin t)^2+( \cos t)^2} = 1 \\ \text{Third step:} & \vecs T(t) & = & \dfrac{\vecs r′(t)}{‖\vecs r′(t)‖}=\dfrac{− \sin t \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \cos t \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}}{1}=− \sin t \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \cos t \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} \end{array}\)

- \(\begin{array}{lrcl} \text{First step:} & \vecs r′(t) & = & (6t+2) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}−12t^2 \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+6 \,\hat{\mathbf{k}} \\ \text{Second step:} & ‖\vecs r′(t)‖ & = & \sqrt{(6t+2)^2+(−12t^2)^2+6^2} \\ \text{} & \text{} & = & \sqrt{144t^4+36t^2+24t+40} \\ \text{} & \text{} & = & 2 \sqrt{36t^4+9t^2+6t+10} \\ \text{Third step:} & \vecs T(t) & = & \dfrac{\vecs r′(t)}{‖\vecs r′(t)‖}=\dfrac{(6t+2) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}−12t^2 \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+6 \,\hat{\mathbf{k}}}{2 \sqrt{36t^4+9t^2+6t+10}} \\ \text{} & \text{} & = & \dfrac{3t+1}{\sqrt{36t^4+9t^2+6t+10}} \,\hat{\mathbf{i}} - \dfrac{6t^2}{\sqrt{36t^4+9t^2+6t+10}} \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} + \dfrac{3}{\sqrt{36t^4+9t^2+6t+10}} \,\hat{\mathbf{k}} \end{array}\)

Find the unit tangent vector for the vector-valued function

\[\vecs r(t)=(t^2−3)\,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(2t+1) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+(t−2) \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}. \nonumber \]

- Hint

-

Follow the same steps as in Example \(\PageIndex{4}\).

- Answer

-

\[\vecs T(t)=\dfrac{2t}{\sqrt{4t^2+5}}\,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+\dfrac{2}{\sqrt{4t^2+5}}\,\mathbf{\hat{j}}+\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{4t^2+5}}\,\mathbf{\hat{k}} \nonumber \]

Integrals of Vector-Valued Functions

We introduced antiderivatives of real-valued functions in Antiderivatives and definite integrals of real-valued functions in The Definite Integral. Each of these concepts can be extended to vector-valued functions. Also, just as we can calculate the derivative of a vector-valued function by differentiating the component functions separately, we can calculate the antiderivative in the same manner. Furthermore, the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus applies to vector-valued functions as well.

The antiderivative of a vector-valued function appears in applications. For example, if a vector-valued function represents the velocity of an object at time t, then its antiderivative represents position. Or, if the function represents the acceleration of the object at a given time, then the antiderivative represents its velocity.

Let \(f\), \(g\), and \(h\) be integrable real-valued functions over the closed interval \([a,b].\)

- The indefinite integral of a vector-valued function \(\vecs{r}(t)=f(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+g(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}\) is

\[\int [f(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+g(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}]\,dt= \left[ \int f(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \left[ \int g(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}. \nonumber \]

The definite integral of a vector-valued function is\[\int_a^b [f(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+g(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}]\,dt = \left[ \int_a^b f(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \left[ \int_a^b g(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}. \nonumber \]

- The indefinite integral of a vector-valued function \(\vecs r(t)=f(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+g(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+h(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{k}}\) is

\[\int [f(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+g(t)\,\hat{\mathbf{j}} + h(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{k}}]\,dt= \left[ \int f(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \left[ \int g(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} + \left[ \int h(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{k}}. \nonumber \]

The definite integral of the vector-valued function is\[\int_a^b [f(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+g(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} + h(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{k}}]\,dt= \left[ \int_a^b f(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \left[ \int_a^b g(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} + \left[ \int_a^b h(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{k}}. \nonumber \]

Since the indefinite integral of a vector-valued function involves indefinite integrals of the component functions, each of these component integrals contains an integration constant. They can all be different. For example, in the two-dimensional case, we can have

\[\int f(t)\,dt=F(t)+C_1 \; and \; \int g(t)\,dt=G(t)+C_2, \nonumber \]

where \(F\) and \(G\) are antiderivatives of \(f\) and \(g\), respectively. Then

\[\begin{align*} \int [f(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+g(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}]\,dt &= \left[ \int f(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \left[ \int g(t)\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} \\[4pt]

&= (F(t)+C_1) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(G(t)+C_2) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} \\[4pt]

&=F(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+G(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+C_1 \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+C_2 \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} \\[4pt]

&= F(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+G(t) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+\vecs{C} \end{align*}\]

where \(\vecs{C}=C_1 \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+C_2 \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}\). Therefore, the integration constants becomes a constant vector.

Calculate each of the following integrals:

- \( \displaystyle \int [(3t^2+2t) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(3t−6) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+(6t^3+5t^2−4) \,\hat{\mathbf{k}}]\,dt\)

- \( \displaystyle \int [⟨t,t^2,t^3⟩ \times ⟨t^3,t^2,t⟩] \,dt\)

- \( \displaystyle \int_{0}^{\frac{\pi}{3}} [\sin 2t \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \tan t \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+e^{−2t} \,\hat{\mathbf{k}}]\,dt\)

Solution

- We use the first part of the definition of the integral of a space curve:

- \[\begin{align*} \int[(3t^2+2t)\,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(3t−6) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+(6t^3+5t^2−4)\,\hat{\mathbf{k}}]\,dt &=\left[\int 3t^2+2t\,dt \right]\,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \left[\int 3t−6\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+ \left[\int 6t^3+5t^2−4\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{k}} \\[4pt]

&=(t^3+t^2) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+\left(\frac{3}{2}t^2−6t\right) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+\left(\frac{3}{2}t^4+\frac{5}{3}t^3−4t\right)\,\hat{\mathbf{k}}+\vecs C. \end{align*}\] - First calculate \(⟨t,t^2,t^3⟩ \times ⟨t^3,t^2,t⟩:\)

\[\begin{align*} ⟨t,t^2,t^3⟩ \times ⟨t^3,t^2,t⟩ &= \begin{vmatrix} \hat{\mathbf{i}} & \,\hat{\mathbf{j}} & \,\hat{\mathbf{k}} \\ t & t^2 & t^3 \\ t^3 & t^2 & t \end{vmatrix} \\[4pt]

Next, substitute this back into the integral and integrate:

&=(t^2(t)−t^3(t^2)) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}−(t^2−t^3(t^3))\,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+(t(t^2)−t^2(t^3))\,\hat{\mathbf{k}} \\[4pt]

&=(t^3−t^5)\,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(t^6−t^2)\,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+(t^3−t^5)\,\hat{\mathbf{k}}. \end{align*} \nonumber \]\[\begin{align*} \int [⟨t,t^2,t^3⟩ \times ⟨t^3,t^2,t⟩]\,dt &= \int (t^3−t^5) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(t^6−t^2) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+(t^3−t^5)\,\hat{\mathbf{k}}\,dt \\[4pt]

&=\left(\frac{t^4}{4}−\frac{t^6}{6}\right)\,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+\left(\frac{t^7}{7}−\frac{t^3}{3}\right)\,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+\left(\frac{t^4}{4}−\frac{t^6}{6}\right)\,\hat{\mathbf{k}}+\vecs C. \end{align*}\] - Use the second part of the definition of the integral of a space curve:

\[\begin{align*} \int_0^{\frac{\pi}{3}} [\sin 2t \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \tan t \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+e^{−2t} \,\hat{\mathbf{k}}]\,dt &=\left[\int_0^{\frac{π}{3}} \sin 2t \,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+ \left[ \int_0^{\frac{π}{3}} \tan t \,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+\left[\int_0^{\frac{π}{3}}e^{−2t}\,dt \right] \,\hat{\mathbf{k}} \\[4pt]

&= (-\tfrac{1}{2} \cos 2t) \Big\vert_{0}^{π/3} \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}−( \ln |\cos t|)\Big\vert_{0}^{π/3} \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}−\left(\tfrac{1}{2}e^{−2t}\right)\Big\vert_{0}^{π/3} \,\hat{\mathbf{k}} \\[4pt]

&=\left(−\tfrac{1}{2} \cos \tfrac{2π}{3}+\tfrac{1}{2} \cos 0\right) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}−\left( \ln \left( \cos \tfrac{π}{3}\right)− \ln( \cos 0)\right) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}−\left( \tfrac{1}{2}e^{−2π/3}−\tfrac{1}{2}e^{−2(0)}\right) \,\hat{\mathbf{k}} \\[4pt]

& =\left(\tfrac{1}{4}+\tfrac{1}{2}\right) \,\hat{\mathbf{i}}−(−\ln 2) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}−\left(\tfrac{1}{2}e^{−2π/3}−\tfrac{1}{2}\right) \,\hat{\mathbf{k}} \\[4pt]

&=\tfrac{3}{4}\,\hat{\mathbf{i}}+(\ln 2) \,\hat{\mathbf{j}}+\left(\tfrac{1}{2}−\tfrac{1}{2}e^{−2π/3}\right)\,\hat{\mathbf{k}}. \end{align*}\]

Calculate the following integral:

\[\int_1^3 [(2t+4) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(3t^2−4t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}]\,dt \nonumber \]

- Hint

-

Use the definition of the definite integral of a plane curve.

- Answer

-

\[\int_1^3 [(2t+4) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+(3t^2−4t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}}]\,dt = 16 \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+10 \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} \nonumber \]

Summary

- To calculate the derivative of a vector-valued function, calculate the derivatives of the component functions, then put them back into a new vector-valued function.

- Many of the properties of differentiation of scalar functions also apply to vector-valued functions.

- The derivative of a vector-valued function \(\vecs r(t)\) is also a tangent vector to the curve. The unit tangent vector \(\vecs T(t)\) is calculated by dividing the derivative of a vector-valued function by its magnitude.

- The antiderivative of a vector-valued function is found by finding the antiderivatives of the component functions, then putting them back together in a vector-valued function.

- The definite integral of a vector-valued function is found by finding the definite integrals of the component functions, then putting them back together in a vector-valued function.

Key Equations

- Derivative of a vector-valued function\[\vecs r′(t) = \lim \limits_{\Delta t \to 0} \dfrac{\vecs r(t+\Delta t)−\vecs r(t)}{ \Delta t} \nonumber \]

- Principal unit tangent vector \[\vecs T(t)=\frac{\vecs r′(t)}{‖\vecs r′(t)‖} \nonumber \]

- Indefinite integral of a vector-valued function \[\int [f(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g(t)\,\mathbf{\hat{j}} + h(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}]\,dt= \left[ \int f(t)\,dt \right] \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+ \left[ \int g(t)\,dt \right] \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} + \left[ \int h(t)\,dt \right] \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\nonumber \]

- Definite integral of a vector-valued function \[\int_a^b [f(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+g(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} + h(t) \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}]\,dt= \left[\int_a^b f(t)\,dt \right] \,\mathbf{\hat{i}}+ \left[ \int _a^b g(t)\,dt \right] \,\mathbf{\hat{j}} + \left[ \int _a^b h(t)\,dt \right] \,\mathbf{\hat{k}}\nonumber \]

Glossary

- definite integral of a vector-valued function

- the vector obtained by calculating the definite integral of each of the component functions of a given vector-valued function, then using the results as the components of the resulting function

- derivative of a vector-valued function

- the derivative of a vector-valued function \(\vecs{r}(t)\) is \(\vecs{r}′(t) = \lim \limits_{\Delta t \to 0} \frac{\vecs r(t+\Delta t)−\vecs r(t)}{ \Delta t}\), provided the limit exists

- indefinite integral of a vector-valued function

- a vector-valued function with a derivative that is equal to a given vector-valued function

- principal unit tangent vector

- a unit vector tangent to a curve C

- tangent vector

- to \(\vecs{r}(t)\) at \(t=t_0\) any vector \(\vecs v\) such that, when the tail of the vector is placed at point \(\vecs r(t_0)\) on the graph, vector \(\vecs{v}\) is tangent to curve C