12.1: Minimum Weight Spanning Trees

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

In this section, we consider pairs

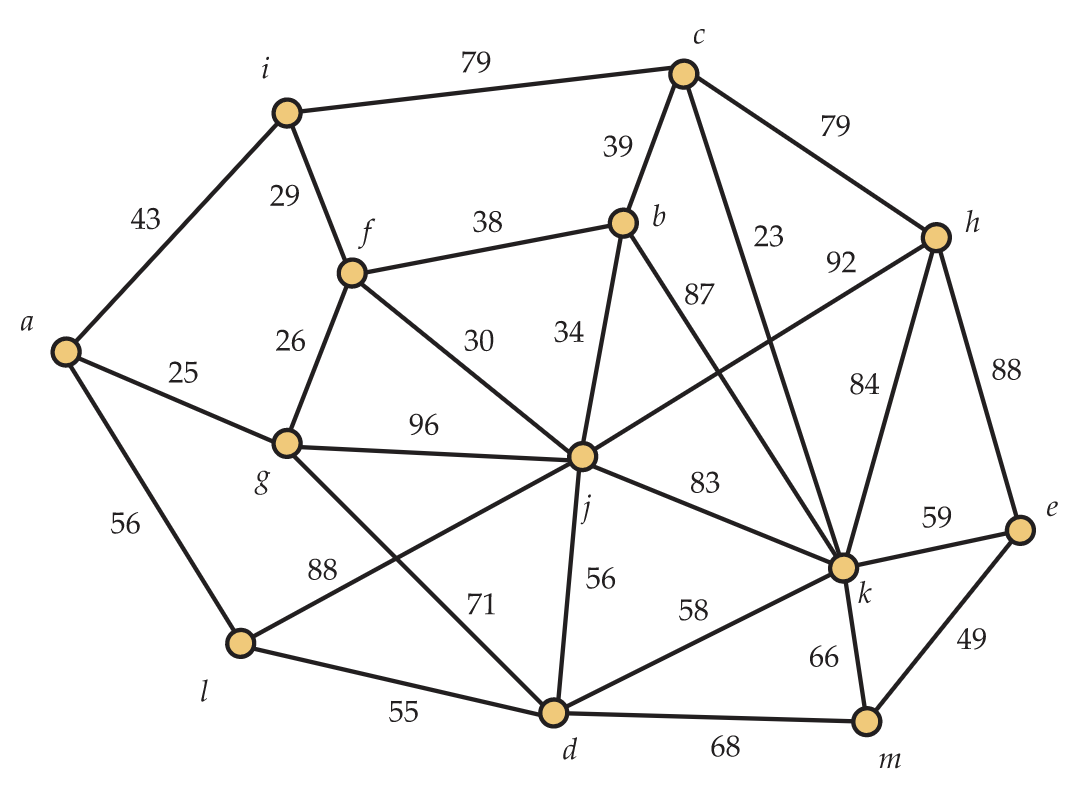

Weighted graphs arise in many contexts. One of the most natural is when the weights on the edges are distances or costs. For example, consider the weighted graph in Figure 12.1. Suppose the vertices represent nodes of a network and the edges represent the ability to establish direct physical connections between those nodes. The weights associated to the edges represent the cost (let's say in thousands of dollars) of building those connections. The company establishing the network among the nodes only cares that there is a way to get data between each pair of nodes. Any additional links would create redundancy in which they are not interested at this time. A spanning tree of the graph ensures that each node can communicate with each of the others and has no redundancy, since removing any edge disconnects it. Thus, to minimize the cost of building the network, we want to find a minimum weight (or cost) spanning tree.

To do this, this section considers the following problem:

Find a minimum weight spanning tree

To solve this problem, we will develop two efficient graph algorithms, each having certain computational advantages and disadvantages. Before developing the algorithms, we need to establish some preliminaries about spanning trees and forests.

12.1.1 Preliminaries

The following proposition about the number of components in a spanning forest of a graph

Proposition 12.3

Let

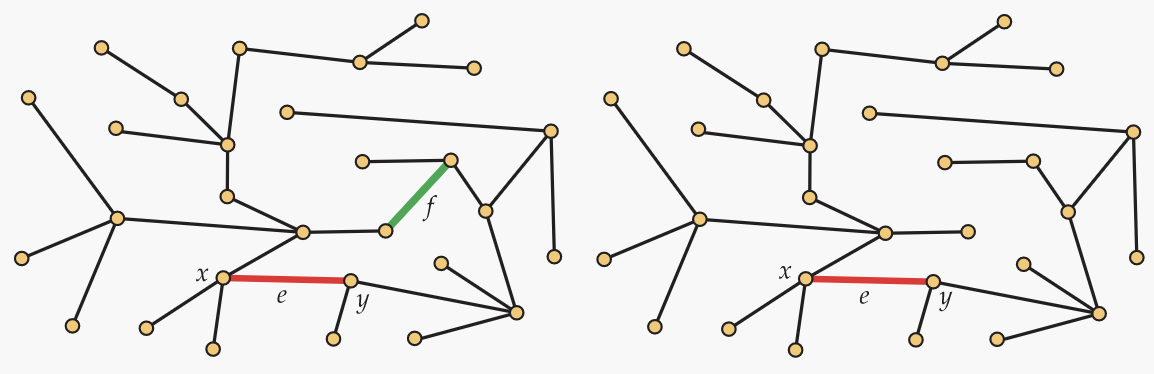

The following proposition establishes a way to take a spanning tree of a graph, remove an edge from it, and add an edge of the graph that is not in the spanning tree to create a new spanning tree. Effectively, the process exchanges two edges to form the new spanning tree, so we call this the exchange principle.

Let

- There is a unique path

- For each

i.e., we exchange edge

- Proof

-

For the first fact, it suffices to note that if there were more than one distinct path from

Figure 12.5. The exchange principle

For both of the algorithms we develop, the argument to show that the algorithm is optimal rests on the following technical lemma. To avoid trivialities, we assume

Let

- Proof

-

Let

Let

Although Bob's combinatorial intuition has improved over the course he doesn't quite understand why we need special algorithms to find minimum weight spanning trees. He figures there can't be that many spanning trees, so he wants to just write them down. Alice groans as she senses that Bob must have been absent when the material from Section 5.6 was discussed. In that section, we learned that a graph on

12.1.2 Kruskal's Algorithm

In this section, we develop one of the best known algorithms for finding a minimum weight spanning tree. It is known as Kruskal's Algorithm, although some prefer the descriptive label Avoid Cycles because of the way it builds the spanning tree.

To start Kruskal's algorithm, we sort the edges according to weight. To be more precise, let m denote the number of edges in

Once the edges are sorted, Kruskal's algorithm proceeds to an initialization step and then inductively builds the spanning tree

Initialization. Set

Inductive Step. While

The correctness of Kruskal's Algorithm follows from an inductive argument. First, the set

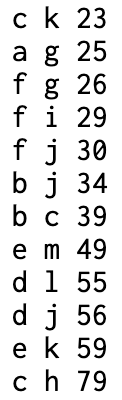

Let's see what Kruskal's algorithm does on the weighted graph in Figure 12.1. It first sorts all of the edges by weight. We won't reproduce the list here, since we won't need all of it. The edge of least weight is

12.1.3 Prim's Algorithm

We now develop Prim's Algorithm for finding a minimum weight spanning tree. This algorithm is also known by a more descriptive label: Build Tree. We begin by choosing a root vertex

Initialization. Set

Inductive Step. While

The correctness of Prim's algorithm follows immediately from Lemma 12.6.

Let's see what Prim's algorithm does on the weighted graph in Figure 12.1. We start with vertex

a g 25 f g 26 f i 29 f j 30 b j 34 b c 39 c k 23 a l 56 d l 55 e k 59 e m 49 c h 79

12.1.4 Comments on Efficiency

An implementation of Kruskal's algorithm seems to require that the edges be sorted. If the graph has

On the other hand, an implementation of Prim's algorithm requires the program to conveniently keep track of the edges incident with each vertex and always be able to identify the edge with least weight among subsets of these edges. In computer science, the data structure that enables this task to be carried out is called a heap.