5.2: Application of Eigenfunction Series

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

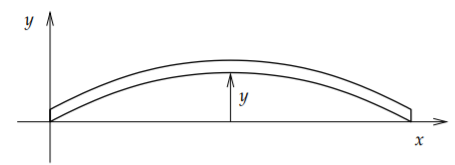

The eigenfunction series can arise even from higher order equations. Consider an elastic beam (say made of steel). We will study the transversal vibrations of the beam. That is, suppose the beam lies along the x-axis and let y(x,t) measure the displacement of the point x on the beam at time t. See Figure 5.2.1.

The equation that governs this setup is

a4∂4y∂x4+∂2y∂t2=0,

for some constant a>0, let us not worry about the physics1.

Suppose the beam is of length 1 simply supported (hinged) at the ends. The beam is displaced by some function f(x) at time t=0 and then let go (initial velocity is 0). Then y satisfies:

a4yxxxx+ytt=0(0<x<1,t>0),y(0,t)=yxx(0,t)=0,y(1,t)=yxx(1,t)=0,y(x,0)=f(x),yt(x,0)=0.

Again we try y(x,t)=X(x)T(t) and plug in to get a4X(4)T+XT″=0 or

X(4)X=−T″a4T=λ.

The equations are T″+λa4T=0,X(4)−λX=0. The boundary conditions y(0,t)=yxx(0,t)=0 and y(1,t)=yxx(1,t)=0 imply X(0)=X″(0)=0,andX(1)=X″(1)=0.

The initial homogeneous condition yt(x,0)=0 implies T′(0)=0. As usual, we leave the nonhomogeneous y(x,0)=f(x) for later.

Considering the equation for T, that is, T″+λa4T=0, and physical intuition leads us to the fact that if λ is an eigenvalue then λ>0: We expect vibration and not exponential growth nor decay in the t direction (there is no friction in our model for instance). So there are no negative eigenvalues. Similarly λ=0 is not an eigenvalue.

Justify λ>0 just from the equation for X and the boundary conditions.

Write ω4=λ, so that we do not need to write the fourth root all the time. For X we get the equation X(4)−ω4X=0. The general solution is

X(x)=Aeωx+Be−ωx+Csin(ωx)+Dcos(ωx).

Now 0=X(0)A+B+D,0=X″(0)=ω2(A+B−D). Hence, D=0 and A+B=0, or B=−A. So we have

X(x)=Aeωx−Ae−ωx+Csin(ωx).

Also 0=X(1)=A(eω−e−ω)+Csinω, and 0=X″(1)=Aω2(eω−e−ω)−Cω2sinω. This means that Csinω=0 and A(eω−e−ω)=2Asinhω=0. If ω>0, then ω≠0 and so A=0. This means that C≠0 otherwise λ is not an eigenvalue. Also ω must be an integer multiple of π. Hence ω=nπ and n≥1 (as ω>0). We can take C=1. So the eigenvalues are λn=n4π4 and the eigenfunctions are sin(nπx).

Now T″+n4π4a4T=0. The general solution is T(t)=Asin(n2π2a2t)+Bcos(n2π2a2t). But T′(0)=0 and hence we must have A=0 and we can take B=1 to make T(0)=1 for convenience. So our solutions are Tn(t)=cos(n2π2a2t).

As the eigenfunctions are just sines again, we can decompose the function f(x) on 0<x<1 using the sine series. We find numbers bn such that for 0<x<1 we have

f(x)=∞∑n=1bnsin(nπx).

Then the solution to (5.2.2) is

y(x,t)=∞∑n=1bnXn(x)Tn(t)=∞∑n=1bnsin(nπx)cos(n2π2a2t).

The point is that XnTn is a solution that satisfies all the homogeneous conditions (that is, all conditions except the initial position). And since and Tn(0)=1, we have

y(x,0)=∞∑n=1bnXn(x)Tn(0)=∞∑n=1bnXn(x)=∞∑n=1bnsin(nπx)=f(x).

So y(x,t) solves (5.2.2).

The natural (circular) frequencies of the system are n2π2a2. These frequencies are all integer multiples of the fundamental frequency π2a2, so we get a nice musical note. The exact frequencies and their amplitude are what we call the timbre of the note.

The timbre of a beam is different than for a vibrating string where we get “more” of the lower frequencies since we get all integer multiples, 1,2,3,4,5,…. For a steel beam we get only the square multiples 1,4,9,16,25,…. That is why when you hit a steel beam you hear a very pure sound. The sound of a xylophone or vibraphone is, therefore, very different from a guitar or piano.

Let us assume that f(x)=x(x−1)10. On 0<x<1 we have (you know how to do this by now)

f(x)=∞∑n=1n odd45π3n3sin(nπx).

Hence, the solution to (5.2.2) with the given initial position f(x) is

y(x,t)=∞∑n=1n odd45π3n3sin(nπx)cos(n2π2a2t).

There are other boundary conditions than just hinged ends. There are three basic possibilities: hinged, free, or fixed. Let us consider the end at x=0. For the other end, it is the same idea. If the end is hinged, then u(0,t)=uxx(0,t)=0. If the end is free, that is, it is just floating in air, then uxx(0,t)=uxxx(0,t)=0. And finally, if the end is clamped or fixed, for example it is welded to a wall, then u(0,t)=ux(0,t)=0.

Footnotes

[1] If you are interested, a4=EIρ, where E is the elastic modulus, I is the second moment of area of the cross section, and ρ is linear density.