A.5: Inner Product and Projections

- Page ID

- 73039

Inner Product and Orthogonality

To do basic geometry, we need length, and we need angles. We have already seen the euclidean length, so let us figure out how to compute angles. Mostly, we are worried about the right angle\(^{1}\).

Given two (column) vectors in \({\mathbb{R}}^n\), we define the (standard) inner product as the dot product: \[\langle \vec{x} , \vec{y} \rangle = \vec{x} \cdot \vec{y} = \vec{y}^T \vec{x} = x_1 y_1 + x_2 y_2 + \cdots + x_n y_n = \sum_{i=1}^n x_i y_i . \nonumber \] Why do we seemingly give a new notation for the dot product? Because there are other possible inner products, which are not the dot product, although we will not worry about others here. An inner product can even be defined on spaces of functions as we do in Chapter 4: \[\langle f(t) , g(t) \rangle = \int_{a}^{b} f(t) g(t) \, dt . \nonumber \] But we digress.

The inner product satisfies the following rules:

- \(\langle \vec{x} , \vec{x} \rangle \geq 0\), and \(\langle \vec{x} , \vec{x} \rangle = 0\) if and only if \(\vec{x} = 0\),

- \(\langle \vec{x} , \vec{y} \rangle = \langle \vec{y} , \vec{x} \rangle\),

- \(\langle a\vec{x} , \vec{y} \rangle = \langle \vec{x} , a\vec{y} \rangle = a \langle \vec{x} , \vec{y} \rangle\),

- \(\langle \vec{x} + \vec{y} , \vec{z} \rangle = \langle \vec{x} , \vec{z} \rangle + \langle \vec{y} , \vec{z} \rangle\) and \(\langle \vec{x}, \vec{y} + \vec{z} \rangle = \langle \vec{x} , \vec{y} \rangle + \langle \vec{x} , \vec{z} \rangle\).

Anything that satisfies the properties above can be called an inner product, although in this section we are concerned with the standard inner product in \({\mathbb{R}}^n\).

The standard inner product gives the euclidean length: \[\lVert{\vec{x}}\rVert = \sqrt{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{x} \rangle} = \sqrt{x_1^2 + x_2^2 + \cdots + x_n^2} . \nonumber \] How does it give angles?

You may recall from multivariable calculus, that in two or three dimensions, the standard inner product (the dot product) gives you the angle between the vectors: \[\langle \vec{x}, \vec{y} \rangle = \lVert{\vec{x}}\rVert \lVert{\vec{y}}\rVert \cos \theta. \nonumber \] That is, \(\theta\) is the angle that \(\vec{x}\) and \(\vec{y}\) make when they are based at the same point.

In \({\mathbb{R}}^n\) (any dimension), we are simply going to say that \(\theta\) from the formula is what the angle is. This makes sense as any two vectors based at the origin lie in a 2-dimensional plane (subspace), and the formula works in 2 dimensions. In fact, one could even talk about angles between functions this way, and we do in Chapter 4, where we talk about orthogonal functions (functions at right angle to each other).

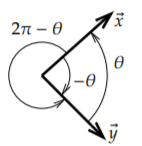

To compute the angle we compute \[\cos \theta = \frac{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{y} \rangle}{\lVert{\vec{x}}\rVert \lVert{\vec{y}}\rVert} . \nonumber \] Our angles are always in radians. We are computing the cosine of the angle, which is really the best we can do. Given two vectors at an angle \(\theta\), we can give the angle as \(-\theta\), \(2\pi-\theta\), etc., see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). Fortunately, \(\cos \theta = \cos (-\theta) = \cos(2\pi - \theta)\). If we solve for \(\theta\) using the inverse cosine \(\cos^{-1}\), we can just decree that \(0 \leq \theta \leq \pi\).

Let us compute the angle between the vectors \((3,0)\) and \((1,1)\) in the plane. Compute \[\cos \theta = \frac{\bigl\langle (3,0) , (1,1) \bigr\rangle}{\lVert(3,0)\rVert \lVert(1,1)\rVert} = \frac{3 + 0}{3 \sqrt{2}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} . \nonumber \] Therefore \(\theta = \frac{\pi}{4}\).

As we said, the most important angle is the right angle. A right angle is \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) radians, and \(\cos (\frac{\pi}{2}) = 0\), so the formula is particularly easy in this case. We say vectors \(\vec{x}\) and \(\vec{y}\) are orthogonal if they are at right angles, that is if \[\langle \vec{x} , \vec{y} \rangle = 0 . \nonumber \] The vectors \((1,0,0,1)\) and \((1,2,3,-1)\) are orthogonal. So are \((1,1)\) and \((1,-1)\). However, \((1,1)\) and \((1,2)\) are not orthogonal as their inner product is \(3\) and not \(0\).

Orthogonal Projection

A typical application of linear algebra is to take a difficult problem, write everything in the right basis, and in this new basis the problem becomes simple. A particularly useful basis is an orthogonal basis, that is a basis where all the basis vectors are orthogonal. When we draw a coordinate system in two or three dimensions, we almost always draw our axes as orthogonal to each other.

Generalizing this concept to functions, it is particularly useful in Chapter 4 to express a function using a particular orthogonal basis, the Fourier series.

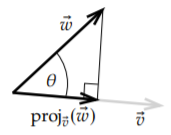

To express one vector in terms of an orthogonal basis, we need to first project one vector onto another. Given a nonzero vector \(\vec{v}\), we define the orthogonal projection of \(\vec{w}\) onto \(\vec{v}\) as \[\operatorname{proj}_{\vec{v}}(\vec{w}) = \left( \frac{\langle \vec{w} , \vec{v} \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v} , \vec{v} \rangle} \right) \vec{v} . \nonumber \] For the geometric idea, see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). That is, we find the "shadow of \(\vec{w}\)" on the line spanned by \(\vec{v}\) if the direction of the sun’s rays were exactly perpendicular to the line. Another way of thinking about it is that the tip of the arrow of \(\operatorname{proj}_{\vec{v}}(\vec{w})\) is the closest point on the line spanned by \(\vec{v}\) to the tip of the arrow of \(\vec{w}\). In terms of euclidean distance, \(\vec{u} = \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{v}}(\vec{w})\) minimizes the distance \(\lVert \vec{w} - \vec{u} \rVert\) among all vectors \(\vec{u}\) that are multiples of \(\vec{v}\). Because of this, this projection comes up often in applied mathematics in all sorts of contexts we cannot solve a problem exactly: We can’t always solve "Find \(\vec{w}\) as a multiple of \(\vec{v}\)" but \(\operatorname{proj}_{\vec{v}}(\vec{w})\) is the best "solution."

The formula follows from basic trigonometry. The length of \(\operatorname{proj}_{\vec{v}}(\vec{w})\) should be \(\cos \theta\) times the length of \(\vec{w}\), that is \((\cos \theta)\lVert\vec{w}\rVert\). We take the unit vector in the direction of \(\vec{v}\), that is, \(\frac{\vec{v}}{\lVert \vec{v} \rVert}\) and we multiply it by the length of the projection. In other words, \[\operatorname{proj}_{\vec{v}}(\vec{w}) = (\cos \theta) \lVert \vec{w} \rVert \frac{\vec{v}}{\lVert \vec{v} \rVert} = \frac{(\cos \theta) \lVert \vec{w} \rVert \lVert \vec{v} \rVert}{ {\lVert \vec{v} \rVert}^2 } \vec{v} = \frac{\langle \vec{w}, \vec{v} \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v}, \vec{v} \rangle } \vec{v} . \nonumber \]

Suppose we wish to project the vector \((3,2,1)\) onto the vector \((1,2,3)\). Compute \[\begin{align}\begin{aligned} \operatorname{proj}_{(1,2,3)} \bigl( (3,2,1) \bigr) = \frac{\langle (3,2,1) , (1,2,3) \rangle}{\langle (1,2,3) , (1,2,3) \rangle} (1,2,3) & = \frac{3 \cdot 1 + 2 \cdot 2 + 1 \cdot 3}{ 1 \cdot 1 + 2 \cdot 2 + 3 \cdot 3} (1,2,3) \\ & = \frac{10}{14} (1,2,3) = \left(\frac{5}{7},\frac{10}{7},\frac{15}{7}\right) . \end{aligned}\end{align} \nonumber \] Let us double check that the projection is orthogonal. That is \(\vec{w}-\operatorname{proj}_{\vec{v}}(\vec{w})\) ought to be orthogonal to \(\vec{v}\), see the right angle in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). That is, \[(3,2,1) - \operatorname{proj}_{(1,2,3)} \bigl( (3,2,1) \bigr) = \left(3-\frac{5}{7},2-\frac{10}{7},1-\frac{15}{7}\right) = \left(\frac{16}{7},\frac{4}{7},\frac{-8}{7}\right) \nonumber \] ought to be orthogonal to \((1,2,3)\). We compute the inner product and we had better get zero: \[\left\langle \left(\frac{16}{7},\frac{4}{7},\frac{-8}{7}\right) , (1,2,3) \right\rangle = \frac{16}{7} \cdot 1 + \frac{4}{7} \cdot 2 -\frac{8}{7} \cdot 3 = 0 . \nonumber \]

Orthogonal Basis

As we said, a basis \(\vec{v}_1,\vec{v}_2,\ldots,\vec{v}_n\) is an orthogonal basis if all vectors in the basis are orthogonal to each other, that is, if \[\langle \vec{v}_j , \vec{v}_k \rangle = 0 \nonumber \] for all choices of \(j\) and \(k\) where \(j \not= k\) (a nonzero vector cannot be orthogonal to itself). A basis is furthermore called an orthonormal basis if all the vectors in a basis are also unit vectors, that is, if all the vectors have magnitude 1. For example, the standard basis \(\{ (1,0,0), (0,1,0), (0,0,1) \}\) is an orthonormal basis of \({\mathbb{R}}^3\): Any pair is orthogonal, and each vector is of unit magnitude.

The reason why we are interested in orthogonal (or orthonormal) bases is that they make it really simple to represent a vector (or a projection onto a subspace) in the basis. The simple formula for the orthogonal projection onto a vector gives us the coefficients. In Chapter 4, we use the same idea by finding the correct orthogonal basis for the set of solutions of a differential equation. We are then able to find any particular solution by simply applying the orthogonal projection formula, which is just a couple of a inner products.

Let us come back to linear algebra. Suppose that we have a subspace and an orthogonal basis \(\vec{v}_1, \vec{v}_2, \ldots, \vec{v}_n\). We wish to express \(\vec{x}\) in terms of the basis. If \(\vec{x}\) is not in the span of the basis (when it is not in the given subspace), then of course it is not possible, but the following formula gives us at least the orthogonal projection onto the subspace, or in other words, the best approximation in the subspace.

First suppose that \(\vec{x}\) is in the span. Then it is the sum of the orthogonal projections: \[\vec{x} = \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{v}_1} ( \vec{x} ) + \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{v}_2} ( \vec{x} ) + \cdots + \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{v}_n} ( \vec{x} ) = \frac{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{v}_1 \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v}_1, \vec{v}_1 \rangle } \vec{v}_1 + \frac{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{v}_2 \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v}_2, \vec{v}_2 \rangle } \vec{v}_2 + \cdots + \frac{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{v}_n \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v}_n, \vec{v}_n \rangle } \vec{v}_n . \nonumber \] In other words, if we want to write \(\vec{x} = a_1 \vec{v}_1 + a_2 \vec{v}_2 + \cdots + a_n \vec{v}_n\), then \[a_1 = \frac{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{v}_1 \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v}_1, \vec{v}_1 \rangle } , \quad a_2 = \frac{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{v}_2 \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v}_2, \vec{v}_2 \rangle } , \quad \ldots , \quad a_n = \frac{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{v}_n \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v}_n, \vec{v}_n \rangle } . \nonumber \] Another way to derive this formula is to work in reverse. Suppose that \(\vec{x} = a_1 \vec{v}_1 + a_2 \vec{v}_2 + \cdots + a_n \vec{v}_n\). Take an inner product with \(\vec{v}_j\), and use the properties of the inner product: \[\begin{align}\begin{aligned} \langle \vec{x} , \vec{v}_j \rangle & = \langle a_1 \vec{v}_1 + a_2 \vec{v}_2 + \cdots + a_n \vec{v}_n , \vec{v}_j \rangle \\ & = a_1 \langle \vec{v}_1 , \vec{v}_j \rangle + a_2 \langle \vec{v}_2 , \vec{v}_j \rangle + \cdots + a_n \langle \vec{v}_n , \vec{v}_j \rangle . \end{aligned}\end{align} \nonumber \] As the basis is orthogonal, then \(\langle \vec{v}_k , \vec{v}_j \rangle = 0\) whenever \(k \not= j\). That means that only one of the terms, the \(j^{\text{th}}\) one, on the right hand side is nonzero and we get \[\langle \vec{x} , \vec{v}_j \rangle = a_j \langle \vec{v}_j , \vec{v}_j \rangle . \nonumber \] Solving for \(a_j\) we find \(a_j = \frac{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{v}_j \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v}_j, \vec{v}_j \rangle }\) as before.

The vectors \((1,1)\) and \((1,-1)\) form an orthogonal basis of \({\mathbb{R}}^2\). Suppose we wish to represent \((3,4)\) in terms of this basis, that is, we wish to find \(a_1\) and \(a_2\) such that \[(3,4) = a_1 (1,1) + a_2 (1,-1) . \nonumber \] We compute: \[a_1 = \frac{\langle (3,4), (1,1) \rangle}{ \langle (1,1), (1,1) \rangle } = \frac{7}{2}, \qquad a_2 = \frac{\langle (3,4), (1,-1) \rangle}{ \langle (1,-1), (1,-1) \rangle } = \frac{-1}{2} . \nonumber \] So \[(3,4) = \frac{7}{2} (1,1) + \frac{-1}{2} (1,-1) . \nonumber \]

If the basis is orthonormal rather than orthogonal, then all the denominators are one. It is easy to make a basis orthonormal—divide all the vectors by their size. If you want to decompose many vectors, it may be better to find an orthonormal basis. In the example above, the orthonormal basis we would thus create is \[\left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} , \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \right) , \quad \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} , \frac{-1}{\sqrt{2}} \right) . \nonumber \] Then the computation would have been \[\begin{align}\begin{aligned} (3,4) & = \left\langle (3,4) , \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} , \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \right) \right\rangle \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} , \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \right) + \left\langle (3,4) , \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} , \frac{-1}{\sqrt{2}} \right) \right\rangle \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} , \frac{-1}{\sqrt{2}} \right) \\ & = \frac{7}{\sqrt{2}} \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} , \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \right) + \frac{-1}{\sqrt{2}} \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} , \frac{-1}{\sqrt{2}} \right) . \end{aligned}\end{align} \nonumber \] Maybe the example is not so awe inspiring, but given vectors in \({\mathbb{R}}^{20}\) rather than \({\mathbb{R}}^2\), then surely one would much rather do 20 inner products (or 40 if we did not have an orthonormal basis) rather than solving a system of twenty equations in twenty unknowns using row reduction of a \(20 \times 21\) matrix.

As we said above, the formula still works even if \(\vec{x}\) is not in the subspace, although then it does not get us the vector \(\vec{x}\) but its projection. More concretely, suppose that \(S\) is a subspace that is the span of \(\vec{v}_1,\vec{v}_2,\ldots,\vec{v}_n\) and \(\vec{x}\) is any vector. Let \(\operatorname{proj}_{S}(\vec{x})\) be the vector in \(S\) that is the closest to \(\vec{x}\). Then \[\operatorname{proj}_{S}(\vec{x}) = \frac{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{v}_1 \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v}_1, \vec{v}_1 \rangle } \vec{v}_1 + \frac{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{v}_2 \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v}_2, \vec{v}_2 \rangle } \vec{v}_2 + \cdots + \frac{\langle \vec{x}, \vec{v}_n \rangle}{ \langle \vec{v}_n, \vec{v}_n \rangle } \vec{v}_n . \nonumber \] Of course, if \(\vec{x}\) is in \(S\), then \(\operatorname{proj}_{S}(\vec{x}) = \vec{x}\), as the closest vector in \(S\) to \(\vec{x}\) is \(\vec{x}\) itself. But true utility is obtained when \(\vec{x}\) is not in \(S\). In much of applied mathematics, we cannot find an exact solution to a problem, but we try to find the best solution out of a small subset (subspace). The partial sums of Fourier series from Chapter 4 are one example. Another example is least square approximation to fit a curve to data. Yet another example is given by the most commonly used numerical methods to solve partial differential equations, the finite element methods.

The vectors \((1,2,3)\) and \((3,0,-1)\) are orthogonal, and so they are an orthogonal basis of a subspace \(S\): \[S = \operatorname{span} \bigl\{ (1,2,3), (3,0,-1) \bigr\} . \nonumber \] Let us find the vector in \(S\) that is closest to \((2,1,0)\). That is, let us find \(\operatorname{proj}_{S}\bigl((2,1,0)\bigr)\). \[\begin{align}\begin{aligned} \operatorname{proj}_{S}\bigl((2,1,0)\bigr) & = \frac{\langle (2,1,0), (1,2,3) \rangle}{ \langle (1,2,3), (1,2,3) \rangle } (1,2,3) + \frac{\langle (2,1,0), (3,0,-1) \rangle}{ \langle (3,0,-1), (3,0,-1) \rangle } (3,0,-1) \\ & = \frac{2}{7} (1,2,3) + \frac{3}{5} (3,0,-1) \\ &= \left( \frac{73}{35} , \frac{4}{7} , \frac{9}{35} \right) . \end{aligned}\end{align} \nonumber \]

Gram–Schmidt Process

Before leaving orthogonal bases, let us note a procedure for manufacturing them out of any old basis. It may not be difficult to come up with an orthogonal basis for a 2-dimensional subspace, but for a 20-dimensional subspace, it seems a daunting task. Fortunately, the orthogonal projection can be used to "project away" the bits of the vectors that are making them not orthogonal. It is called the Gram-Schmidt process.

We start with a basis of vectors \(\vec{v}_1,\vec{v}_2, \ldots, \vec{v}_n\). We construct an orthogonal basis \(\vec{w}_1, \vec{w}_2, \ldots, \vec{w}_n\) as follows. \[\begin{align}\begin{aligned} \vec{w}_1 & = \vec{v}_1 , \\ \vec{w}_2 & = \vec{v}_2 - \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{w}_1}(\vec{v}_2) , \\ \vec{w}_3 & = \vec{v}_3 - \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{w}_1}(\vec{v}_3) - \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{w}_2}(\vec{v}_3) , \\ \vec{w}_4 & = \vec{v}_4 - \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{w}_1}(\vec{v}_4) - \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{w}_2}(\vec{v}_4) - \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{w}_3}(\vec{v}_4) , \\ & \vdots \\ \vec{w}_n & = \vec{v}_n - \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{w}_1}(\vec{v}_n) - \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{w}_2}(\vec{v}_n) - \cdots - \operatorname{proj}_{\vec{w}_{n-1}}(\vec{v}_n) .\end{aligned}\end{align} \nonumber \] What we do is at the \(k^{\text{th}}\) step, we take \(\vec{v}_k\) and we subtract the projection of \(\vec{v}_k\) to the subspace spanned by \(\vec{w}_1,\vec{w}_2,\ldots,\vec{w}_{k-1}\).

Consider the vectors \((1,2,-1)\), and \((0,5,-2)\) and call \(S\) the span of the two vectors. Let us find an orthogonal basis of \(S\): \[\begin{align}\begin{aligned} \vec{w}_1 & = (1,2,-1) , \\ \vec{w}_2 & = (0,5,-2) - \operatorname{proj}_{(1,2,-1)}\bigl((0,2,-2)\bigr) \\ & = (0,1,-1) - \frac{\langle (0,5,-2), (1,2,-1) \rangle}{ \langle (1,2,-1), (1,2,-1) \rangle } (1,2,-1) = (0,5,-2) - 2 (1,2,-1) = (-2,1,0) .\end{aligned}\end{align} \nonumber \] So \((1,2,-1)\) and \((-2,1,0)\) span \(S\) and are orthogonal. Let us check: \(\langle (1,2,-1) , (-2,1,0) \rangle = 0\).

Suppose we wish to find an orthonormal basis, not just an orthogonal one. Well, we simply make the vectors into unit vectors by dividing them by their magnitude. The two vectors making up the orthonormal basis of \(S\) are: \[\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} (1,2,-1) = \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}, \frac{2}{\sqrt{6}}, \frac{-1}{\sqrt{6}} \right) , \qquad \frac{1}{\sqrt{5}} (-2,1,0) = \left( \frac{-2}{\sqrt{5}}, \frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}, 0 \right) . \nonumber \]

Footnotes

[1] When Euclid defined angles in his Elements, the only angle he ever really defined was the right angle.