6.4: Motion Under a Central Force

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

We’ll now study the motion of a object moving under the influence of a central force; that is, a force whose magnitude at any point P other than the origin depends only on the distance from P to the origin, and whose direction at P is parallel to the line connecting P and the origin, as indicated in Figure 6.4.1 for the case where the direction of the force at every point is toward the origin. Gravitational forces are central forces; for example, as mentioned in Section 4.3, if we assume that Earth is a perfect sphere with constant mass density then Newton’s law of gravitation asserts that the force exerted on an object by Earth’s gravitational field is proportional to the mass of the object and inversely proportional to the square of its distance from the center of Earth, which we take to be the origin.

If the initial position and velocity vectors of an object moving under a central force are parallel, then the subsequent motion is along the line from the origin to the initial position. Here we’ll assume that the initial position and velocity vectors are not parallel; in this case the subsequent motion is in the plane determined by them. For convenience we take this to be the xy-plane. We’ll consider the problem of determining the curve traversed by the object. We call this curve the orbit.

We can represent a central force in terms of polar coordinates

x=rcosθ,y=rsinθ

as

F(r,θ)=f(r)(cosθi+sinθj).

We assume that f is continuous for all r>0. The magnitude of F at (x,y)=(rcosθ,rsinθ) is |f(r)|, so it depends only on the distance r from the point to the origin the direction of F is from the point to the origin if f(r)<0, or from the origin to the point if f(r)>0. We’ll show that the orbit of an object with mass m moving under this force is given by

r(θ)=1u(θ),

where u is solution of the differential equation

d2udθ2+u=−1mh2u2f(1/u),

and h is a constant defined below.

Newton’s second law of motion (F=ma) says that the polar coordinates r=r(t) and θ=θ(t) of the particle satisfy the vector differential equation

m(rcosθi+rsinθj)″=f(r)(cosθi+sinθj).

To deal with this equation we introduce the unit vectors

e1=cosθi+sinθjande2=−sinθi+cosθj.

Note that e1 points in the direction of increasing r and e2 points in the direction of increasing θ (Figure 6.4.2 ); moreover,

de1dθ=e2,de2dθ=−e1,

and

e1⋅e2=cosθ(−sinθ)+sinθcosθ=0,

so e1 and e2 are perpendicular. Recalling that the single prime (′) stands for differentiation with respect to t, we see from Equation ??? and the chain rule that

e′1=θ′e2ande′2=−θ′e1.

Now we can write Equation ??? as

m(re1)″=f(r)e1.

But

(re1)′=r′e1+re′1=r′e1+rθ′e2

(from Equation ???), and

(re1)″=(r′e1+rθ′e2)′=r″e1+r′e′1+(rθ″+r′θ′)e2+rθ′e′2=r″e1+r′θ′e2+(rθ″+r′θ′)e2−r(θ′)2e1from (???)=(r″−r(θ′)2)e1+(rθ″+2r′θ′)e2.

Substituting this into Equation ??? yields

m(r″−r(θ′)2)e1+m(rθ″+2r′θ′)e2=f(r)e1.

By equating the coefficients of e1 and e2 on the two sides of this equation we see that

m(r″−r(θ′)2)=f(r)

and

rθ″+2r′θ′=0.

Multiplying the last equation by r yields

r2θ″+2rr′θ′=(r2θ′)′=0,

so

r2θ′=h,

where h is a constant that we can write in terms of the initial conditions as

h=r2(0)θ′(0).

Since the initial position and velocity vectors are

r(0)e1(0)andr′(0)e1(0)+r(0)θ′(0)e2(0),

our assumption that these two vectors are not parallel implies that θ′(0)≠0, so h≠0.

Now let u=1/r. Then u2=θ′/h (from Equation ???) and

r′=−u′u2=−h(u′θ′),

which implies that

r′=−hdudθ,

since

u′θ′=dudt/dθdt=dudθ.

Differentiating Equation ??? with respect to t yields

r″=−hddt(dudθ)=−hd2udθ2θ′,

which implies that

r″=−h2u2d2udθ2sinceθ′=hu2.

Substituting from these equalities into Equation ??? and recalling that r=1/u yields

−m(h2u2d2udθ2+1uh2u4)=f(1/u),

and dividing through by −mh2u2 yields Equation ???.

Equation ??? has the following geometrical interpretation, which is known as Kepler’s Second Law.

The position vector of an object moving under a central force sweeps out equal areas in equal times; more precisely, if θ(t1)≤θ(t2) then the signed area of the sector (Figure 6.4.3 ):

(x,y)=(rcosθ,rsinθ):0≤r≤r(θ),θ(t1)≤θ(t2)

is given by

A=h(t2−t1)2,

where h=r2θ′, which we have shown to be constant.

- Proof

-

Recall from calculus that the area of the shaded sector in Figure 6.4.3 is

A=12∫θ(t2)θ(t1)r2(θ)dθ,

where r=r(θ) is the polar representation of the orbit. Making the change of variable θ=θ(t) yields

A=12∫t2t1r2(θ(t))θ′(t)dt.

However, Equations ??? and 6.4.28 imply that

A=12∫t2t1hdt=h(t2−t1)2,

which completes the proof.

Motion Under an Inverse Square Law Force

In the special case where f(r)=−mk/r2=−mku2, so F can be interpreted as a gravitational force, Equation ??? becomes

d2udθ2+u=kh2.

The general solution of the complementary equation

d2udθ2+u=0

can be written in amplitude–phase form as

u=Acos(θ−ϕ),

where A≥0 and ϕ is a phase angle. Since up=k/h2 is a particular solution of Equation ???, the general solution of Equation ??? is

u=Acos(θ−ϕ)+kh2;

hence, the orbit is given by

r=(Acos(θ−ϕ)+kh2)−1,

which we rewrite as

r=ρ1+ecos(θ−ϕ),

where

ρ=h2kande=Aρ.

A curve satisfying Equation ??? is a conic section with a focus at the origin (Exercise 6.4.1). The nonnegative constant e is the eccentricity of the orbit, which is an ellipse if e<1 ellipse (a circle if e=0), a parabola if e=1, or a hyperbola if e>1.

If the orbit is an ellipse, then the minimum and maximum values of r are

rmin

Figure 6.4.4 shows a typical elliptic orbit. The point P on the orbit where r=r_{\min} is the perigee and the point A where r=r_{\max} is the apogee.

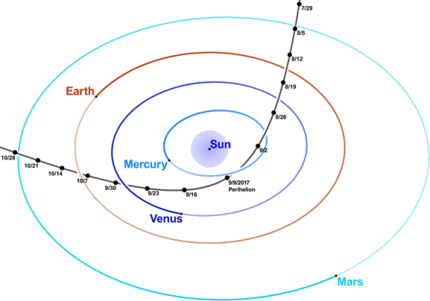

Earth’s orbit around the Sun is approximately an ellipse with e\approx 0.017, r_{\min}\approx 91 \times 10^6 miles, and r_{\max}\approx 95\times 10^6 miles. Halley’s comet has a very elongated approximately elliptical orbit around the sun (Figure \PageIndex{5; left}), with e\approx 0.967, r_{\min}\approx 55 \times10^6 miles, and r_{\max}\approx 33 \times 10^8 miles. Some comets (the nonrecurring type) have parabolic or hyperbolic orbits like the Oumuamua interstellar object (Figure \PageIndex{5; right}).