5.2: Multiply Rational Expressions

- Page ID

- 83137

Multiplying rational expressions is very much the same as fraction multiplication in arithmetic. The numerators are multiplied to numerators. The denominators are multiplied to denominators. The common factors in the numerator and denominator are canceled before multiplying. That’s it! Two examples are shown below. Compare the similarities!

\(\begin{array} &&\text{Multiply rational numbers} && \text{Multiply rational expressions} \\ &\dfrac{3}{20} \cdot \dfrac{4}{9} && \dfrac{2x + 6}{x + 4} \cdot \dfrac{x^2 + 3x − 4}{x^2 − 9} \\ &\dfrac{\cancel{3}}{\cancel{4} \cdot 5} \cdot \dfrac{\cancel{4}}{\cancel{3} \cdot 3} &\textcolor{green}{\text{Factor & Cancel}} & \dfrac{2(\cancel{x + 3})}{\cancel{x + 4}} \cdot \dfrac{(\cancel{x + 4})(x − 1)}{(\cancel{x + 3})(x − 3)} \\ &=\dfrac{1}{5} \cdot \dfrac{1}{3} &\textcolor{green}{\text{What's left?}} & \dfrac{2}{1} \cdot \dfrac{x-1}{x-3} \\ &\dfrac{1 \cdot 1}{5 \cdot 3} &\textcolor{green}{\text{Multiply}} & \dfrac{2(x-1)}{1(x-3)} \\ &\dfrac{1}{15} &\textcolor{green}{\text{Answer!}}& \dfrac{2x-2}{x-3} \end{array}\)

Factoring is key to multiplying rational expressions! Parentheses group expressions. The whole group is seen as a single number, like a package deal. If numerators and denominators are factored, you can cancel common factors, just like with real numbers.

Multiply \(\dfrac{12a^2b}{5c^4} \cdot \dfrac{10c}{9a^2b^2}\)

Solution

The given rational expressions are factored. Find the common factors that cancel. Stay organized to avoid losing track of what’s left after cancelling.

\(\begin{array} &&= \dfrac{3 \cdot 4 \cdot a^2 \cdot b}{5 \cdot c \cdot c^3} \cdot \dfrac{5 \cdot 2 \cdot c}{3 \cdot 3a^2 \cdot b \cdot b} &\text{Multiplication shows cancelable factors.} \\ &= \dfrac{4}{c^3} \cdot \dfrac{2}{3b} &\text{These are the factors left after canceling.} \\ &= \dfrac{4 \cdot 2}{c^3 \cdot 3b} &\text{Multiply numerators. Multiply denominators.} \\ &= \dfrac{8}{3c^3b} &\text{Final inspection. Did we cancel everything? Yes!} \end{array}\)

Opposites

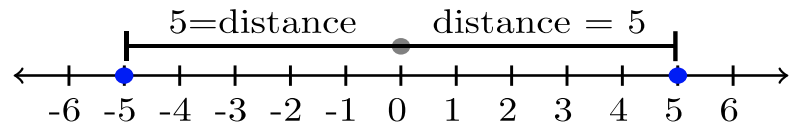

Two numbers are opposites if both numbers have the same distance from zero. For example, \(5\) and \(−5\) are opposites.

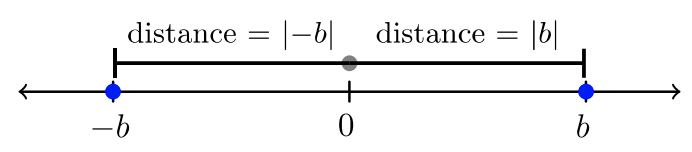

Algebraic Opposites

Algebra generalizes mathematical patterns using variables. If \(b\) is any real number except zero, \(b\) and \(−b\) are opposites.

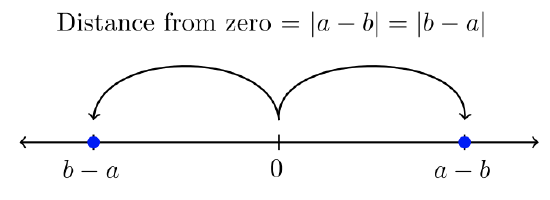

Opposite of a Quantity

Quantities act like one real number. That means the quantity \((a − b)\) should also have an opposite, just like \(5\) has its opposite, \(−5\). Find the opposite of \((a − b)\) in \(3\) steps:

- Put a negative on the entire quantity: \(−(a − b)\)

- Distribute through the negative: \(−a + b\)

- Rearrange the terms: \(b − a\)

\(a-b\) and \(b-a\) are opposites.

\[|a-b| = |b-a|\]

It’s arbitrary which you assign a positive value: \((a − b) > 0\) is pictured above, but you could correctly assign \((b − a) > 0\) making \((a − b) < 0\). In that case, you would swap their marked positions on the number line. Nevertheless, \(|a − b| = |b − a|\).

The Ratio of Opposites

What happens when we take the ratio of opposites? In arithmetic, \(−\dfrac{5}{5} = −\dfrac{1 \cdot 5}{5} = −1\). Now let’s use \(b =\) any real number except zero:

\(\textcolor{green}{\checkmark} \dfrac{-b}{b} = \dfrac{-1 \cdot b}{b} = -1 \cdot \dfrac{b}{b} = -1 \cdot 1 = -1 \)

Since zero in the denominator doesn’t compute, \(b \neq 0\).

\[\dfrac{-b}{b} = \dfrac{b}{-b} = -1 \\ \dfrac{a-b}{b-a} = \dfrac{b-a}{a-b} = -1 \]

Spotting opposites gives us another cancelation opportunity. Opposites in the numerator and denominator cancel to negative \(1\).

Multiply \(\dfrac{y^2−4}{y^2−4y−12} \cdot \dfrac{y^2−7y+6}{2−y}\)

Solution

The given rational expressions are not factored. We can’t cancel before factoring.

\(\begin{array} &&\dfrac{y^2−4}{y^2−4y−12} \cdot \dfrac{y^2−7y+6}{2−y} = \dfrac{(\cancel{y+2})(y−2)}{(\cancel{y+2})(\cancel{y−6})} \cdot \dfrac{(\cancel{y−6})(y−1)}{2−y} &\text{Factor wherever possible. Cancel.} \\ &= \dfrac{\textcolor{red}{y−2}}{1} \cdot \dfrac{y−1}{\textcolor{red}{2−y}} &\text{Notice the opposites! \(\dfrac{y−2}{2−y} = −1\).} \\ &= \textcolor{red}{−1} \cdot (y − 1) &\text{Treat the numerator as a quantity. Use parentheses.} \\& = −y + 1 &\text{Use the distributive property.} \\ &= 1 − y &\text{A positive leading term is preferred.} \end{array}\)

Multiply \(\dfrac{9−4t^2}{16t^2−20t−6} \cdot (1 + 4t)\)

Solution

When multiplying fractions to an integer, we create a fraction of the integer by placing a one in the denominator. Let’s do the same for rational expressions!

\(\begin{array} &\dfrac{9−4t^2}{16t^2−20t−6} \cdot (1 + 4t) &= \dfrac{9−4t^2}{16t^2−20t−6} \cdot \dfrac{1+4t}{1} &\text{Create a fraction. Put a “1” under it!} \\ &= \dfrac{\overbrace{(3 − 2t)( 3 + 2t )}^{\text{Difference of Squares}}}{\underbrace{2(8t^2 − 10t − 3)}_{\text{GCF} = 2}} \cdot \dfrac{1+4t}{1} &\text{Factor. Notice the denominator can be further factored.} \\ &= \dfrac{(3−2t)(3+2t)}{2(\cancel{4t+1})(2t−3)} \cdot \dfrac{\cancel{1+4t}}{1} &\text{Cancel common factors. \(4t + 1 = 1 + 4t\).} \\ &= \dfrac{\textcolor{red}{(3−2t)}(3+2t)}{2 \textcolor{red}{(2t−3)}} &\text{Notice the opposites! \(\dfrac{3−2t}{2t−3} = −1\).} \\ &= \textcolor{red}{−1} \cdot \dfrac{3+2t}{2} &\text{The cancelation of opposites creates a multiplier of \(−1\).} \\&= \dfrac{−1(3+2t)}{2} = \underbrace{\dfrac{-3-2t}{2}}_{\text{Answer #}1} \text{ OR } -1 \cdot \dfrac{3+2t}{2} = \underbrace{-\dfrac{3+2t}{2}}_{\text{Answer #}2} &\text{Which answer do you prefer?} \end{array}\)

Both Answer #1 and Answer #2 are perfectly good answers. Your final answer is your choice!

Try It! (Exercises)

For #1-5, answer the questions about opposites:

- The opposite of \(3\) is\(\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\)

- The opposite of \(−4\) is\(\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\)

- The opposite of \((6 − 4c)\) is\(\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\)

- The opposite of \((2t + 5)\) is\(\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\)

- Opposites in a rational expression cancel to what number?\(\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\)

For #6-8, multiply the rational numbers without using a calculator. Give answer in reduced fraction form.

- \(\dfrac{2^3 \cdot 5^4}{11^6} \cdot \dfrac{11^7 \cdot 3^2}{2^5 \cdot 5^3}\)

- \(6^5 \cdot \dfrac{5^2}{3 \cdot 6^6}\)

- \(\dfrac{4^3 \cdot 2^{10}}{3} \cdot \dfrac{6}{4^2 \cdot 2^{12}} \cdot 2^3\)

For #9-30, multiply and simplify.

- \(\dfrac{4x^5}{9y^4} \cdot \dfrac{27y^2z^3}{8x^5}\)

- \(49u^6 \cdot \dfrac{w^3}{7u^3}\)

- \(\dfrac{10p^8}{9q^2} \cdot \dfrac{18q^5}{25p^9} \cdot 5p\)

- \(\dfrac{(2r−3)^3}{5(4r+1)^2} \cdot \dfrac{15(4r+1)^3}{2r−3}\)

- \(12(3c − 5)^4 \cdot \dfrac{c+1}{6(3c−5)^3}\)

- \(\dfrac{4x+24}{x^2+x−2} \cdot \dfrac{x^2−4}{6x+36}\)

- \(\dfrac{z^2+2z+1}{3z−15} \cdot \dfrac{z^2−6z+5}{z^2+z}\)

- \(\dfrac{y^2−6y−16}{6y−3} \cdot \dfrac{2y^2+y−1}{64−y^2}\)

- \(\dfrac{10−2b}{b^2+5b−14} \cdot \dfrac{b−2}{b^2−3b−10}\)

- \(\dfrac{16h^2+24h+9}{h^2−h-12} \cdot \dfrac{6h^2−24h}{8h^2+6h}\)

- \(\dfrac{6a^2+7a−3}{9a^2−1} \cdot \dfrac{30a+10}{2a+6}\)

- \((2n + 1) \cdot \dfrac{5n}{10n^2+n−2}\)

- \((3p + 7) \cdot \dfrac{2p}{3p^2+13p+14}\)

- \(\dfrac{4d^2−4}{2d^2−20d+18} \cdot (d − 9)\)

- \(\dfrac{4t}{10t−t^2} \cdot (t^2 − 12t + 20)\)

- \(\dfrac{7w^2−7}{w^2+6w+5} \cdot\dfrac{w^2+5w}{14w}\)

- \(\dfrac{1−x}{3x} \cdot \dfrac{x^2−x−42}{3x+18} \cdot \dfrac{27x^2}{x^2−8x+7}\)

- \(\dfrac{4a^2+44a}{9a^2} \cdot \dfrac{63a^3}{a^2+a−20} \cdot \dfrac{a+5}{a^3+11a^2}\)

- \(\dfrac{v^3+1}{v^2−1} \cdot \dfrac{v^2−8v−9}{v^2−2v+1}\)

- \(\dfrac{q^3−8}{q^3−2q^2} \cdot \dfrac{8q^3}{q^2+16q+4}\)

- \(\dfrac{27−8m^3}{m^2−64} \cdot \dfrac{8+m}{2m−3}\)

- \(\dfrac{a^3}{a^2+ab} \cdot \dfrac{a^2−b^2}{ab−a^2}\)

For #31-36, one numerator is left blank. What expression goes in the blank to make the equation true?

- \(\dfrac{x+1}{8x−1} \cdot \dfrac{\textcolor{red}{?}}{x+1} = 1\)

- \(\dfrac{x+1}{8x−1} \cdot \dfrac{\textcolor{red}{?}}{x+1} = −1\)

- \(\dfrac{y^2−4}{y^2−y−6} \cdot \dfrac{\textcolor{red}{?}}{y−2} = 1\)

- \(\dfrac{y^2−4}{y^2−y−6} \cdot \dfrac{\textcolor{red}{?}}{y−2} = −1\)

- \(\dfrac{5u^2}{u−4} \cdot \dfrac{\textcolor{red}{?}}{10u^3} = 1\)

- \(\dfrac{5u^2}{u−4} \cdot \dfrac{\textcolor{red}{?}}{10u^3} = −1\)