5.1: Graphing the Trigonometric Functions

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

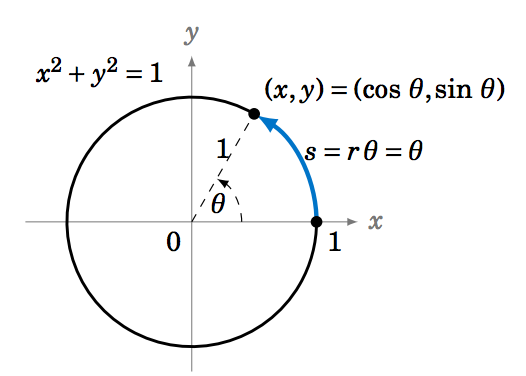

The first function we will graph is the sine function. We will describe a geometrical way to create the graph, using the unit circle. This is the circle of radius 1 in the xy-plane consisting of all points (x,y) which satisfy the equation x2+y2=1.

We see in Figure 5.1.1 that any point on the unit circle has coordinates (x,y)=(cosθ,sinθ), where θ is the angle that the line segment from the origin to (x,y) makes with the positive x-axis (by definition of sine and cosine). So as the point (x,y) goes around the circle, its y-coordinate is sinθ.

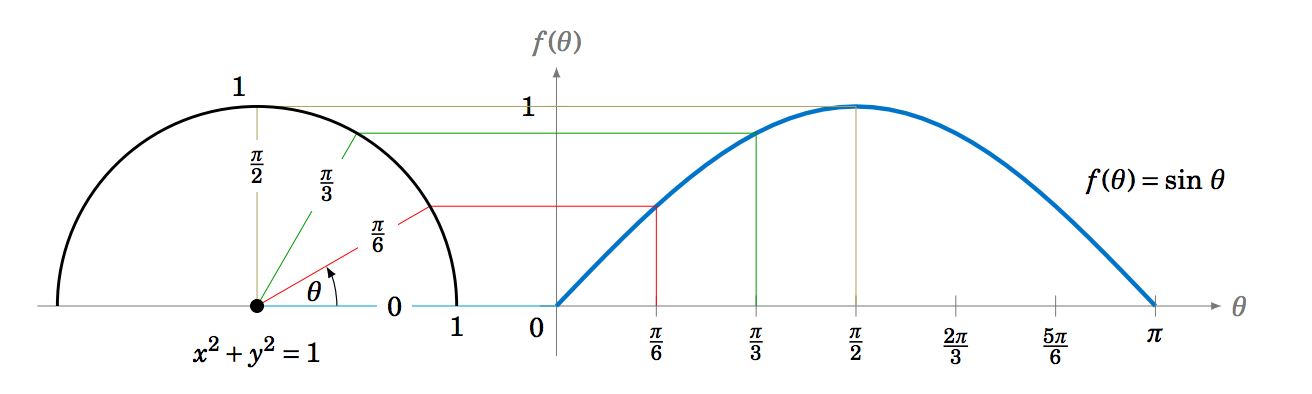

We thus get a correspondence between the y-coordinates of points on the unit circle and the values f(θ)=sinθ, as shown by the horizontal lines from the unit circle to the graph of f(θ)=sinθ in Figure 5.1.2 for the angles θ=0, π6, π3, π2.

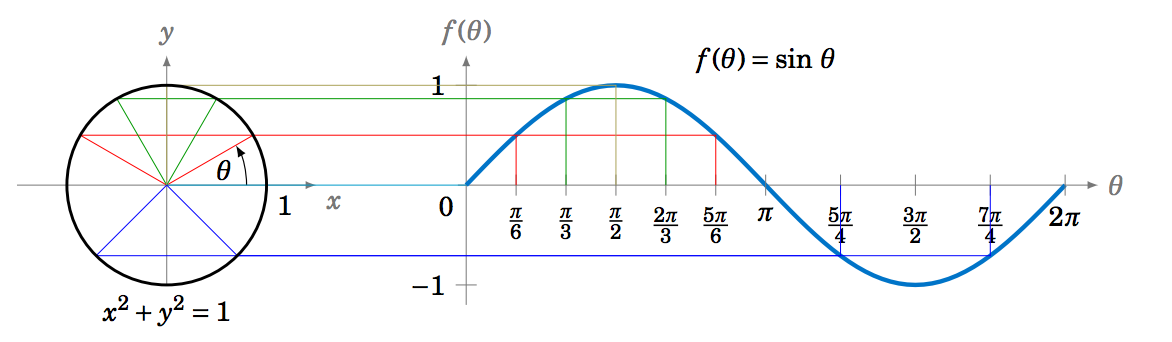

We can extend the above picture to include angles from 0 to 2π radians, as in Figure 5.1.3. This illustrates what is sometimes called the unit circle definition of the sine function.

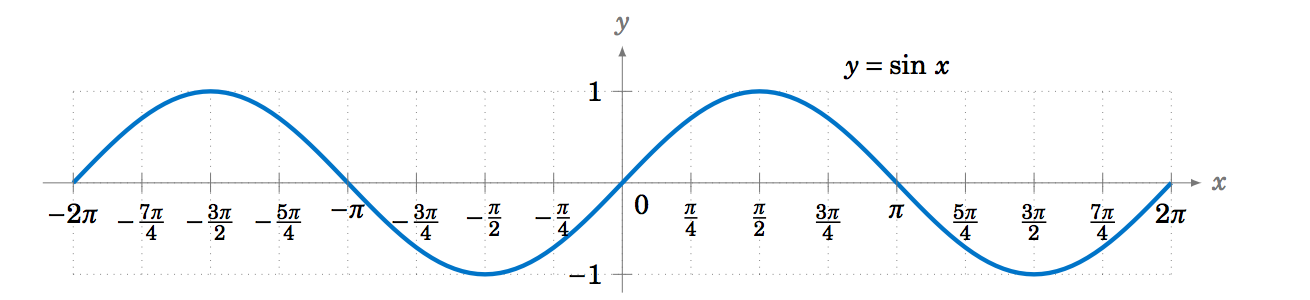

Since the trigonometric functions repeat every 2π radians (360∘), we get, for example, the following graph of the function y=sinx for x in the interval [−2π,2π]:

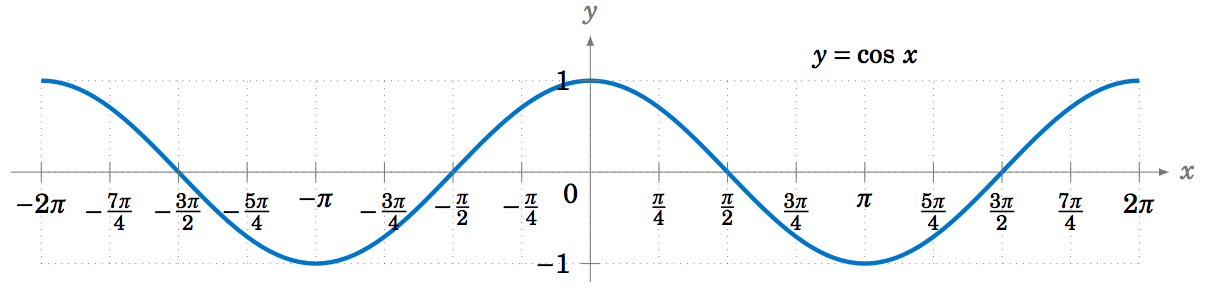

To graph the cosine function, we could again use the unit circle idea (using the x-coordinate of a point that moves around the circle), but there is an easier way. Recall from Section 1.5 that cosx=sin(x+90∘) for all x. So cos0∘ has the same value as sin90∘, cos90∘ has the same value as sin180∘, cos180∘ has the same value as sin270∘, and so on. In other words, the graph of the cosine function is just the graph of the sine function shifted to the left by 90∘=π/2 radians, as in Figure 5.1.5:

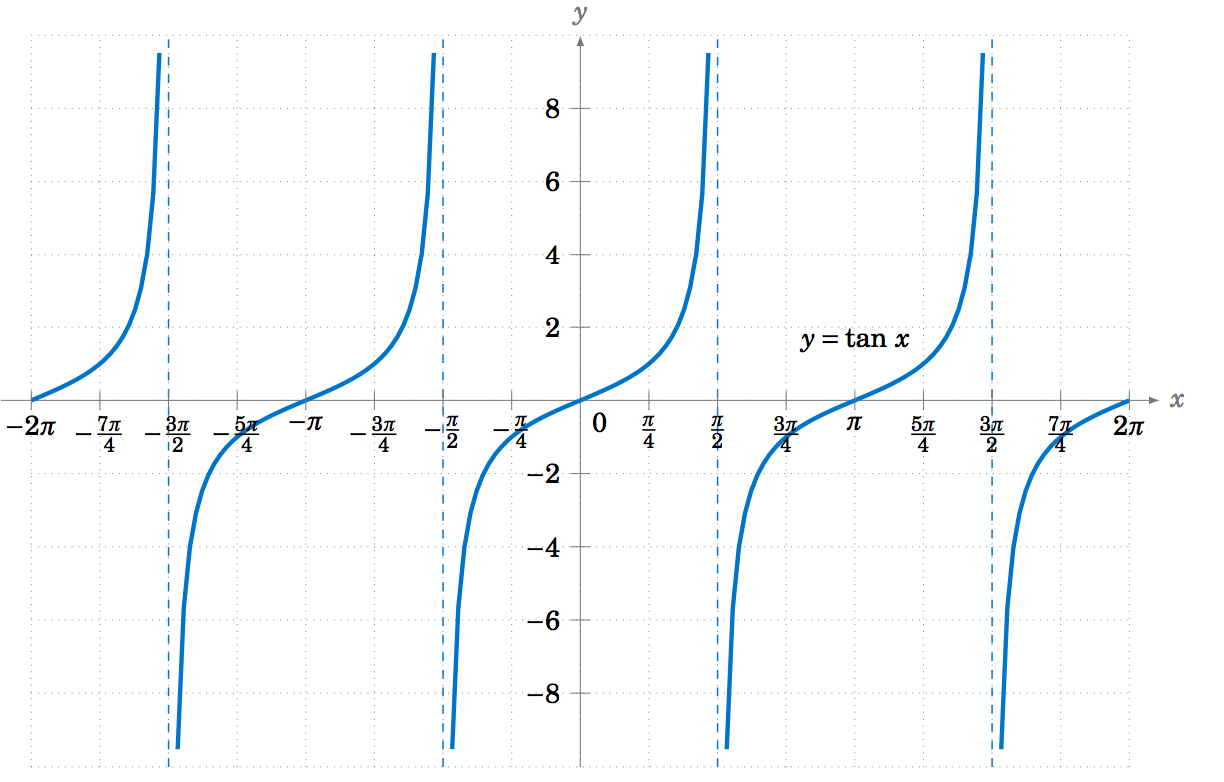

To graph the tangent function, use tanx=sinxcosx to get the following graph:

Recall that the tangent is positive for angles in QI and QIII, and is negative in QII and QIV, and that is indeed what the graph in Figure 5.1.6 shows. We know that tanx is not defined when cosx=0, i.e. at odd multiples of π2: x=±π2, ±3π2, ±5π2, etc. We can figure out what happens near those angles by looking at the sine and cosine functions. For example, for x in QI near π2, sinx and cosx are both positive, with sinx very close to 1 and cosx very close to 0, so the quotient tanx=sinxcosx is a positive number that is very large. And the closer x gets to π2, the larger tanx gets. Thus, x=π2 is a vertical asymptote of the graph of y=tanx.

Likewise, for x in QII very close to π2, sinx is very close to 1 and cosx is negative and very close to 0, so the quotient tanx=sinxcosx is a negative number that is very large, and it gets larger in the negative direction the closer x gets to π2. The graph shows this. Similarly, we get vertical asymptotes at x=−π2, x=3π2, and x=−3π2, as in Figure 5.1.6. Notice that the graph of the tangent function repeats every π radians, i.e. two times faster than the graphs of sine and cosine repeat.

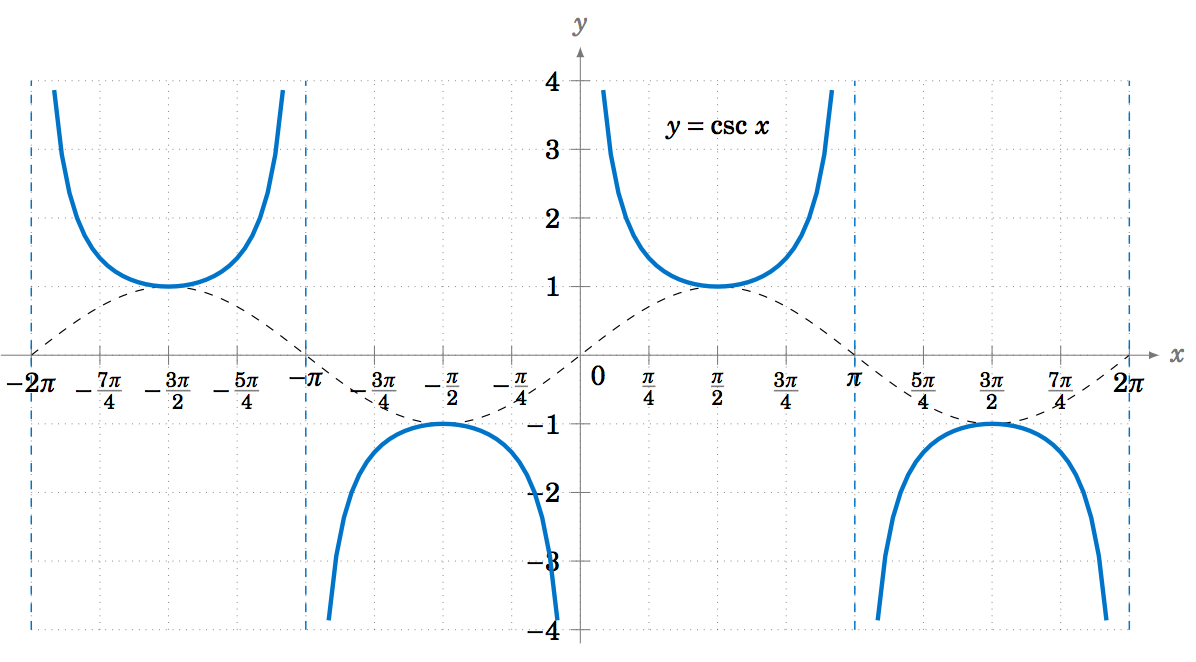

The graphs of the remaining trigonometric functions can be determined by looking at the graphs of their reciprocal functions. For example, using cscx=1sinx we can just look at the graph of y=sinx and invert the values. We will get vertical asymptotes when sinx=0, namely at multiples of π: x=0, ±π, ±2π, etc. Figure 5.1.7 shows the graph of y=cscx, with the graph of y=sinx (the dashed curve) for reference.

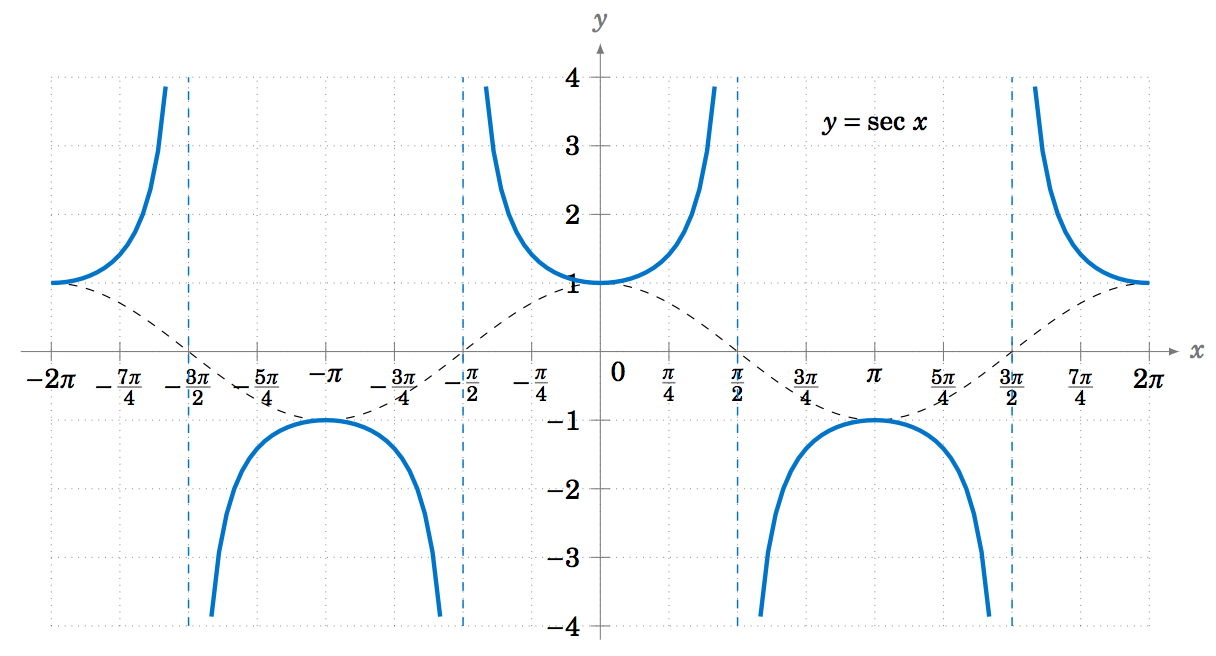

Likewise, Figure 5.1.8 shows the graph of y=secx, with the graph of y=cosx (the dashed curve) for reference. Note the vertical asymptotes at x=±π2, ±3π2. Notice also that the graph is just the graph of the cosecant function shifted to the left by π2 radians.

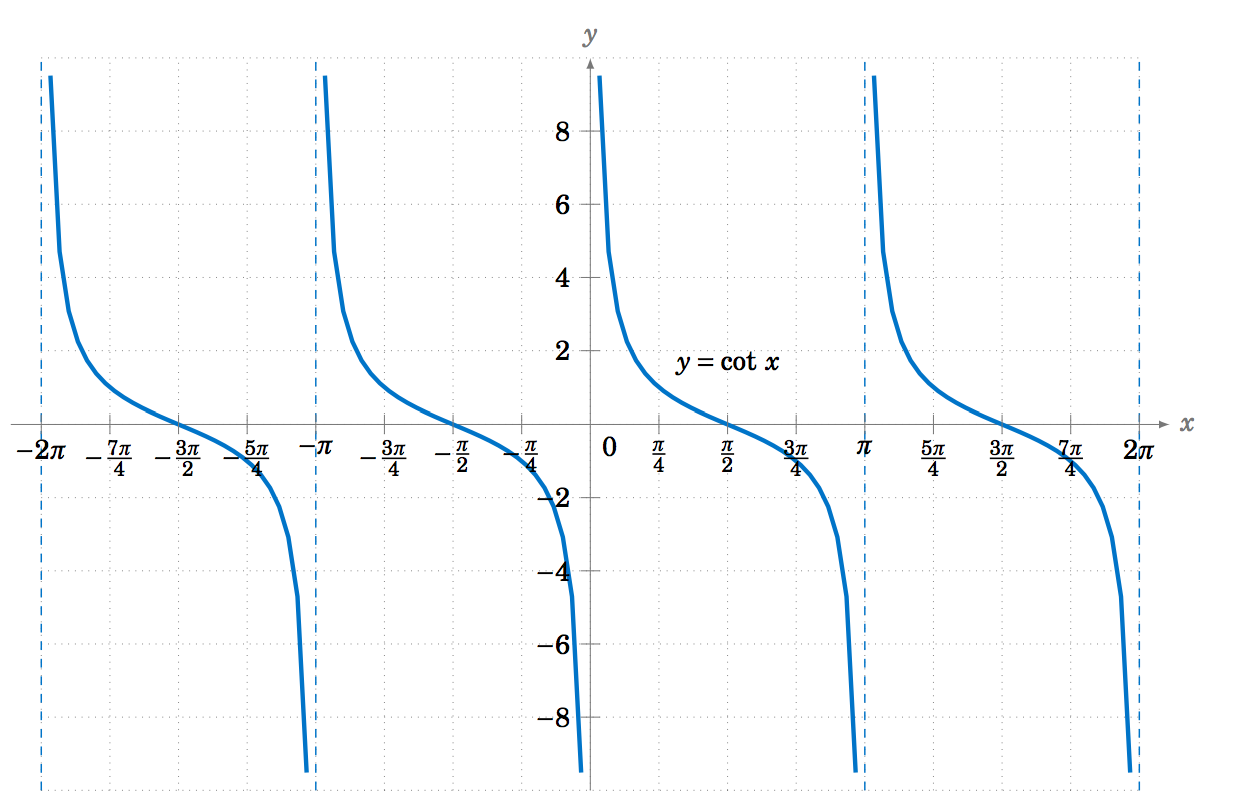

The graph of y=cotx can also be determined by using cotx=1tanx. Alternatively, we can use the relation cotx=−tan(x+90∘) from Section 1.5, so that the graph of the cotangent function is just the graph of the tangent function shifted to the left by π2 radians and then reflected about the x-axis, as in Figure 5.1.9:

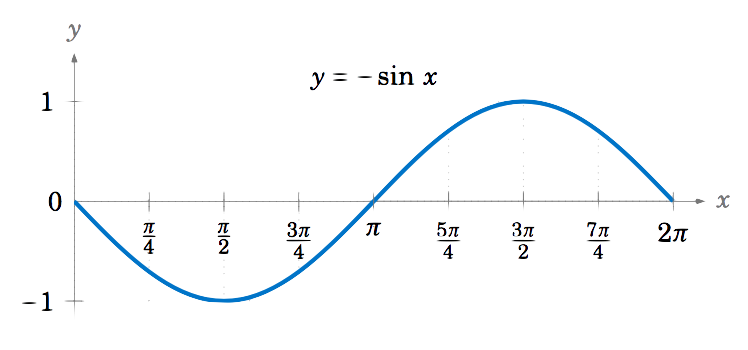

Draw the graph of y=−sinx for 0≤x≤2π.

Solution:

Multiplying a function by −1 just reflects its graph around the x-axis. So reflecting the graph of y=sinx around the x-axis gives us the graph of y=−sinx:

\noindent Note that this graph is the same as the graphs of y=sin(x±π) and y=cos(x+π2).

It is worthwhile to remember the general shapes of the graphs of the six trigonometric functions, especially for sine, cosine, and tangent. In particular, the graphs of the sine and cosine functions are called sinusoidal curves. Many phenomena in nature exhibit sinusoidal behavior, so recognizing the general shape is important.

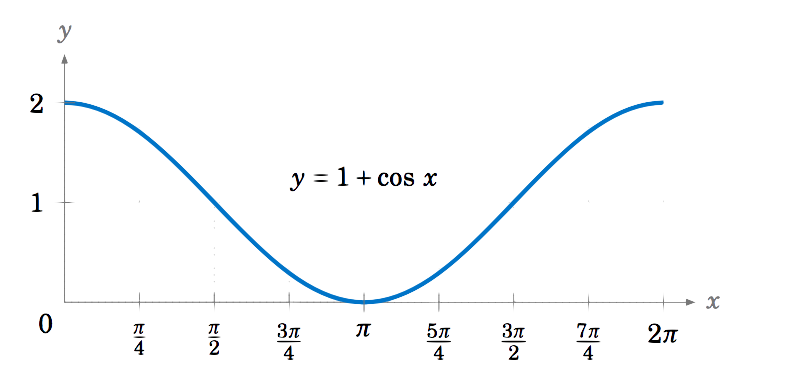

Draw the graph of y=1+cosx for 0≤x≤2π.

Solution

Adding a constant to a function just moves its graph up or down by that amount, depending on whether the constant is positive or negative, respectively. So adding 1 to cosx moves the graph of y=cosx upward by 1, giving us the graph of y=1+cosx: