12.2: Finding Limits - Properties of Limits

- Page ID

- 1404

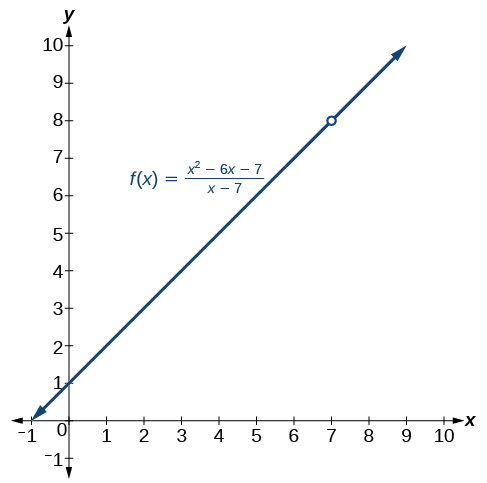

Consider the rational function

\[f(x)=\dfrac{x^2−6x−7}{x−7} \nonumber \]

The function can be factored as follows:

\[f(x)=\dfrac{\cancel{(x−7)}(x+1)}{\cancel{x−7}} \nonumber \]

which gives us

\[f(x)=x+1,x≠7. \nonumber \]

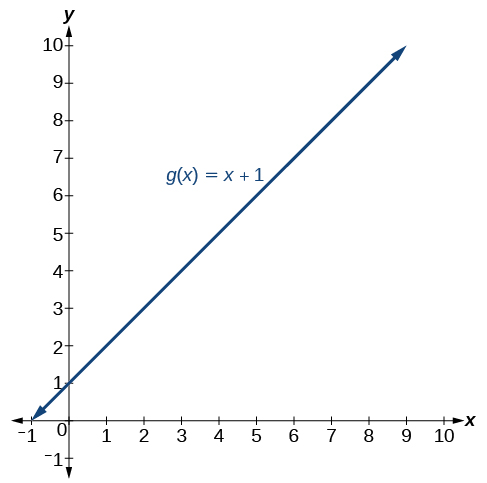

Does this mean the function \(f(x)\) is the same as the function \(g(x)=x+1?\)

The answer is no. Function \(f(x)\) does not have \(x=7\) in its domain, but \(g(x)\) does. Graphically, we observe there is a hole in the graph of \(f(x)\) at \(x=7\), as shown in Figure and no such hole in the graph of \(g(x)\), as shown in Figure.

(left) The graph of function \(f\) contains a break at \(x=7\) and is therefore not continuous at \(x=7\). (Right)The graph of function \(g\) is continuous.

So, do these two different functions also have different limits as \(x\) approaches 7? Not necessarily. Remember, in determining a limit of a function as \(x\) approaches \(a\), what matters is whether the output approaches a real number as we get close to \(x=a\). The existence of a limit does not depend on what happens when \(x\) equals \(a\).

Look again at Figure and Figure. Notice that in both graphs, as \(x\) approaches 7, the output values approach 8. This means

\[ \lim \limits_{x \to 7} f(x)= \lim \limits_{x \to 7} g(x). \nonumber \]

Remember that when determining a limit, the concern is what occurs near \(x=a\), not at \(x=a\). In this section, we will use a variety of methods, such as rewriting functions by factoring, to evaluate the limit. These methods will give us formal verification for what we formerly accomplished by intuition.

Finding the Limit of a Sum, a Difference, and a Product

Graphing a function or exploring a table of values to determine a limit can be cumbersome and time-consuming. When possible, it is more efficient to use the properties of limits, which is a collection of theorems for finding limits.

Knowing the properties of limits allows us to compute limits directly. We can add, subtract, multiply, and divide the limits of functions as if we were performing the operations on the functions themselves to find the limit of the result. Similarly, we can find the limit of a function raised to a power by raising the limit to that power. We can also find the limit of the root of a function by taking the root of the limit. Using these operations on limits, we can find the limits of more complex functions by finding the limits of their simpler component functions.

properties of limits

Let \(a, k, A,\) and \(B\) represent real numbers, and \(f\) and \(g\) be functions, such that \(\lim \limits_{x \to a} f(x)=A\) and \( \lim \limits_{x \to a}g(x)=B.\) For limits that exist and are finite, the properties of limits are summarized in Table

| Constant, k | \(\lim \limits_{x \to a} k=k \) |

| Constant times a function | \(\lim \limits_{x \to a} [k⋅f(x)]=k \lim \limits_{x \to a} f(x)=kA\) |

| Sum of functions | \(\lim \limits_{x \to a} [f(x)+g(x)]= \lim \limits_{x \to a}f(x)+ \lim \limits_{x to a} g(x)=A+B\) |

| Difference of functions | \(\lim \limits_{x \to a} [f(x)−g(x)]= \lim \limits_{x \to a} f(x)− \lim \limits_{x \to a} g(x)=A−B\) |

| Product of functions | \( \lim \limits _{x \to a}[f(x)⋅g(x)]= \lim \limits _{x \to a}f(x)⋅ \lim \limits_{x \to a} g(x)=A⋅B\) |

| Quotient of functions | \(\lim \limits _{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}= \frac{\lim \limits _{x \to a}f(x) }{\lim \limits _{x \to a}g(x)}=\frac{A}{B},B≠0\) |

| Function raised to an exponent | \(\lim \limits _{x \to a}[f(x)]^n=[\lim \limits _{x \to ∞}f(x)]^n=A^n\), where \(n\) is a positive integer |

| nth root of a function, where n is a positive integer | \(\lim \limits _{x \to a}f(x) \sqrt[n]{f(x)} = \sqrt[n]{ \lim \limits _{x \to a}[ f(x) ]}=\sqrt[n]{A}\) |

| Polynomial function | \( \lim \limits _{x \to a} p(x)=p(a)\) |

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Evaluating the Limit of a Function Algebraically

Evaluate \[\lim \limits _{x \to 3}(2x+5). \nonumber \]

Solution

\[\begin{align} \lim \limits _{x \to 3}(2x+5) &= \lim \limits _{x \to 3} (2x)+\lim \limits _{x \to 3}(5) && \text{Sum of functions property} \\ &=2 \lim \limits_{ x \to 3}(x)+\lim \limits _{x \to 3}(5) && \text{Constant times a function property} \\ &=2(3)+5 && \text{Evaluate} \\ &=11 \end{align} \nonumber \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Evaluate the following limit: \[\lim \limits_{x \to −12}(−2x+2). \nonumber \]

Solution

26

Finding the Limit of a Polynomial

Not all functions or their limits involve simple addition, subtraction, or multiplication. Some may include polynomials. Recall that a polynomial is an expression consisting of the sum of two or more terms, each of which consists of a constant and a variable raised to a nonnegative integral power. To find the limit of a polynomial function, we can find the limits of the individual terms of the function, and then add them together. Also, the limit of a polynomial function as \(x\) approaches \(a\) is equivalent to simply evaluating the function for \(a\).

how to: Given a function containing a polynomial, find its limit

- Use the properties of limits to break up the polynomial into individual terms.

- Find the limits of the individual terms.

- Add the limits together.

- Alternatively, evaluate the function for \(a\).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Evaluating the Limit of a Function Algebraically

Evaluate \[ \lim \limits_{x \to 3}(5x ^2). \nonumber \]

Solution

\[\begin{align} \lim \limits_{x \to 3}(5x^2) &= 5 \lim \limits_{x \to 3}(x^2) && \text{Constant times a function property} \\ &=5(3^2) && \text{Function raised to an exponent property} \\&=45 \end{align} \nonumber \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Evaluate \[ \lim \limits_{x \to 4} (x^3−5). \nonumber \]

Solution

59

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Evaluating the Limit of a Polynomial Algebraically

Evaluate \[ \lim \limits_{x \to 5} (2x^3−3x+1). \nonumber \]

Solution

\[\begin{align} \lim \limits_{x \to 5}(2x^3−3x+1) &= \lim \limits_{x \to 5}(2x3)−\lim \limits_{x \to 5}(3x)+\lim \limits_{x \to 5} (1) && \text{Sum of functions}\\ &= 2 \lim \limits_{x \to 5}(x^3)−3 \lim \limits_{x \to 5}(x)+\lim \limits_{x \to 5}(1) && \text{Constant times a function} \\ &=2(5^3)−3(5)+1 && \text{Function raised to an exponent} \\ &=236 &&\text{Evaluate} \end{align} \nonumber \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\):

Evaluate the following limit: \[\lim \limits_{x \to −1}(x^4−4x^3+5). \nonumber \]

Solution

10

Finding the Limit of a Power or a Root

When a limit includes a power or a root, we need another property to help us evaluate it. The square of the limit of a function equals the limit of the square of the function; the same goes for higher powers. Likewise, the square root of the limit of a function equals the limit of the square root of the function; the same holds true for higher roots.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Evaluating a Limit of a Power

Evaluate \[ \lim \limits_{x \to 2}(3x+1)^5. \nonumber \]

Solution

We will take the limit of the function as \(x\) approaches 2 and raise the result to the 5th power.

\[\begin{align} \lim \limits_{x \to 2} (3x+1)^5 &= (\lim \limits_{x \to 2}(3x+1))^5 \\ &=(3(2)+1)^5 \\ &=7^5 \\ &=16,807 \end{align} \nonumber \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\):

Evaluate the following limit: \( \lim \limits_{x \to −4}(10x+36)^3.\)

Solution

−64

Q & A: If we can’t directly apply the properties of a limit, for example in \(\lim \limits_{x \to 2}(\frac{x^2+6x+8}{x−2})\), can we still determine the limit of the function as \(x\) approaches \(a\)?

Yes. Some functions may be algebraically rearranged so that one can evaluate the limit of a simplified equivalent form of the function.

Finding the Limit of a Quotient

Finding the limit of a function expressed as a quotient can be more complicated. We often need to rewrite the function algebraically before applying the properties of a limit. If the denominator evaluates to 0 when we apply the properties of a limit directly, we must rewrite the quotient in a different form. One approach is to write the quotient in factored form and simplify.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Evaluating the Limit of a Quotient by Factoring

Evaluate \[\lim \limits_{x \to 2} (\frac{x^2−6x+8}{x−2}). \nonumber \]

Solution

Factor where possible, and simplify.

\[\begin{align} \lim \limits_{x \to 2} (\dfrac{x^2−6x+8}{x−2}) &= \lim \limits_{x \to 2}(\dfrac{(x−2)(x−4)}{x−2}) && \text{Factor the numerator.} \\ & = \lim \limits_{x \to 2}(\dfrac{\cancel{(x−2)}(x−4)}{\cancel{x−2}}) && \text{Cancel the common factors.} \\ &= \lim \limits_{x \to 2}(x−4) && \text{Evaluate.} \\ & =2−4=−2 \end{align} \nonumber \]

Analysis

When the limit of a rational function cannot be evaluated directly, factored forms of the numerator and denominator may simplify to a result that can be evaluated.

Notice, the function

\[f(x)=\dfrac{x^2−6x+8}{x−2} \nonumber \]

is equivalent to the function

\[f(x)=x−4,x≠2. \nonumber \]

Notice that the limit exists even though the function is not defined at \(x = 2\).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Evaluate the following limit: \[\lim \limits_{x \to 7} \left( \dfrac{x^2−11x+28}{7−x} \right) . \nonumber \]

Solution

\(−3\)

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\): Evaluating the Limit of a Quotient by Finding the LCD

Evaluate \[\lim \limits_{x \to 5} \left( \dfrac{\frac{1}{x}−\frac{1}{5}}{x−5} \right) . \nonumber \]

Solution

Find the LCD for the denominators of the two terms in the numerator, and convert both fractions to have the LCD as their denominator.

Analysis

When determining the limit of a rational function that has terms added or subtracted in either the numerator or denominator, the first step is to find the common denominator of the added or subtracted terms; then, convert both terms to have that denominator, or simplify the rational function by multiplying numerator and denominator by the least common denominator. Then check to see if the resulting numerator and denominator have any common factors.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\):

Evaluate \[\lim \limits_{x \to −5} \left( \dfrac{\frac{1}{5}+\frac{1}{x}}{10+2x} \right). \nonumber \]

Solution

\(−\frac{1}{50}\)

how to: Given a limit of a function containing a root, use a conjugate to evaluate

- If the quotient as given is not in indeterminate \((\frac{0}{0})\) form, evaluate directly.

- Otherwise, rewrite the sum (or difference) of two quotients as a single quotient, using the least common denominator (LCD).

- If the numerator includes a root, rationalize the numerator; multiply the numerator and denominator by the conjugate of the numerator. Recall that \(a±\sqrt{b}\) are conjugates.

- Simplify.

- Evaluate the resulting limit.

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\): Evaluating a Limit Containing a Root Using a Conjugate

Evaluate \[ \lim \limits_{x \to 0} \left( \dfrac{\sqrt{25−x} −5}{x} \right) . \nonumber \]

Solution

\[\begin{align} \lim \limits_{x \to 0} \left( \dfrac{\sqrt{25−x}−5}{x} \right) &= \lim \limits_{x \to 0} \left( \dfrac{(\sqrt{25−x}−5)}{x}⋅\frac{(\sqrt{25−x}+5)}{(\sqrt{25−x}+5)} \right) && \text{Multiply numerator and denominator by the conjugate.} \\ &= \lim \limits_{x \to 0} \left( \dfrac{(25−x)−25}{x(\sqrt{25−x}+5)} \right) && \text{Multiply: } (\sqrt{25−x} −5)⋅(\sqrt{25−x}+5)=(25−x)−25. \\ & = \lim \limits_{x \to 0} \left( \dfrac{−\cancel{x}}{\cancel{x}(25−x+5)} \right) && \text{Combine like terms.} \\ & =\lim \limits_{x \to 0} \left( \dfrac{−\cancel{x}}{\cancel{x}(\sqrt{25−x}+5)} \right) && \text{Simplify }\dfrac{−x}{x}=−1. \\ & =\dfrac{−1}{\sqrt{25−0}+5} && \text{Evaluate.} \\ & =\dfrac{−1}{5+5}=−\dfrac{1}{10} \end{align} \nonumber \]

Analysis

When determining a limit of a function with a root as one of two terms where we cannot evaluate directly, think about multiplying the numerator and denominator by the conjugate of the terms.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Evaluate the following limit: \(\lim \limits_{h \to 0} \left( \dfrac{\sqrt{16−h}−4}{h} \right) \).

Solution

\(−\frac{1}{8}\)

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\): Evaluating the Limit of a Quotient of a Function by Factoring

Evaluate \[\lim \limits_{x \to 4} \left( \frac{4−x}{\sqrt{x−2}} \right). \nonumber \]

Solution

\[\begin{align} \lim \limits_{x \to 4} (\dfrac{4−x}{\sqrt{x}−2}) & = \lim \limits_{x \to 4} (\dfrac{(2+\sqrt{x})(2−x)}{\sqrt{x}−2}) && \text{Factor.} \\ &= \lim \limits_{x \to 4} ( \dfrac{(2+\sqrt{x})(\cancel{2−\sqrt{x}})}{−\cancel{(2−\sqrt{x})}}) && \text{Factor −1 out of the denominator. Simplify.} \\ & = \lim \limits_{x \to 4}−(2+x) && \text{Evaluate.} \\ &=−(2+ \sqrt{4}) \\ &=−4 \end{align} \nonumber \]

Analysis

Multiplying by a conjugate would expand the numerator; look instead for factors in the numerator. Four is a perfect square so that the numerator is in the form

\[a^2−b^2 \nonumber \]

and may be factored as

\[(a+b)(a−b). \nonumber \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{7}\)

Evaluate the following limit: \[\lim \limits_{x \to 3} \left( \frac{x−3}{\sqrt{x}−\sqrt{3} }\right). \nonumber \]

Solution

\(2\sqrt{3}\)

how to: Given a quotient with absolute values, evaluate its limit

- Try factoring or finding the LCD.

- If the limit cannot be found, choose several values close to and on either side of the input where the function is undefined.

- Use the numeric evidence to estimate the limits on both sides.

Example \(\PageIndex{8}\): Evaluating the Limit of a Quotient with Absolute Values

Evaluate \[\lim \limits_{x \to 7} \frac{|x−7|}{x−7}. \nonumber \]

Solution

The function is undefined at \(x=7\), so we will try values close to 7 from the left and the right.

Left-hand limit: \[\frac{|6.9−7|}{6.9−7}=\frac{|6.99−7|}{6.99−7}=\frac{|6.999−7|}{6.999−7}=−1 \nonumber \]

Right-hand limit: \[\frac{|7.1−7|}{7.1−7}=\frac{|7.01−7|}{7.01−7}=\frac{|7.001−7|}{7.001−7}=1 \nonumber \]

Since the left- and right-hand limits are not equal, there is no limit.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{8}\)

Evaluate \[ \lim \limits_{x \to 6^+} \frac{6−x}{| x−6 |}. \nonumber \]

Solution

Key Concepts

- The properties of limits can be used to perform operations on the limits of functions rather than the functions themselves. See Example.

- The limit of a polynomial function can be found by finding the sum of the limits of the individual terms. See Example and Example.

- The limit of a function that has been raised to a power equals the same power of the limit of the function. Another method is direct substitution. See Example.

- The limit of the root of a function equals the corresponding root of the limit of the function.

- One way to find the limit of a function expressed as a quotient is to write the quotient in factored form and simplify. See Example.

- Another method of finding the limit of a complex fraction is to find the LCD. See Example.

- A limit containing a function containing a root may be evaluated using a conjugate. See Example.

- The limits of some functions expressed as quotients can be found by factoring. See Example.

- One way to evaluate the limit of a quotient containing absolute values is by using numeric evidence. Setting it up piecewise can also be useful. See Example.

Glossary

- properties of limits

- a collection of theorems for finding limits of functions by performing mathematical operations on the limits