6.2: Misiurewicz points and the M-set self-similarity

- Page ID

- 102618

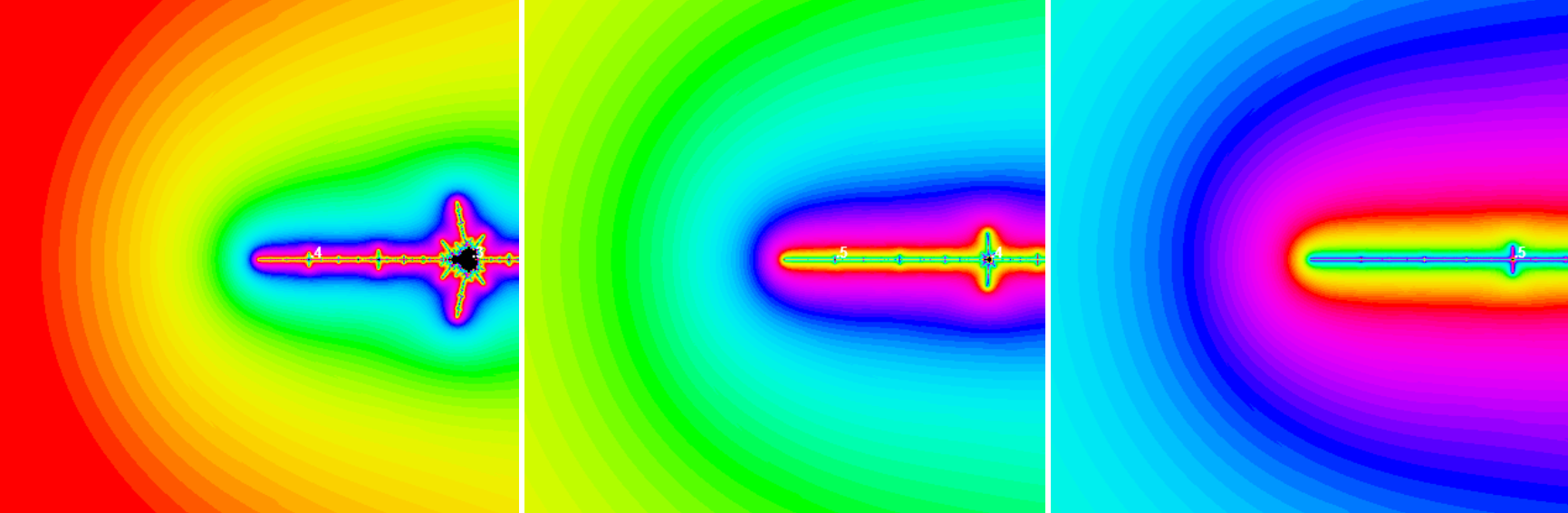

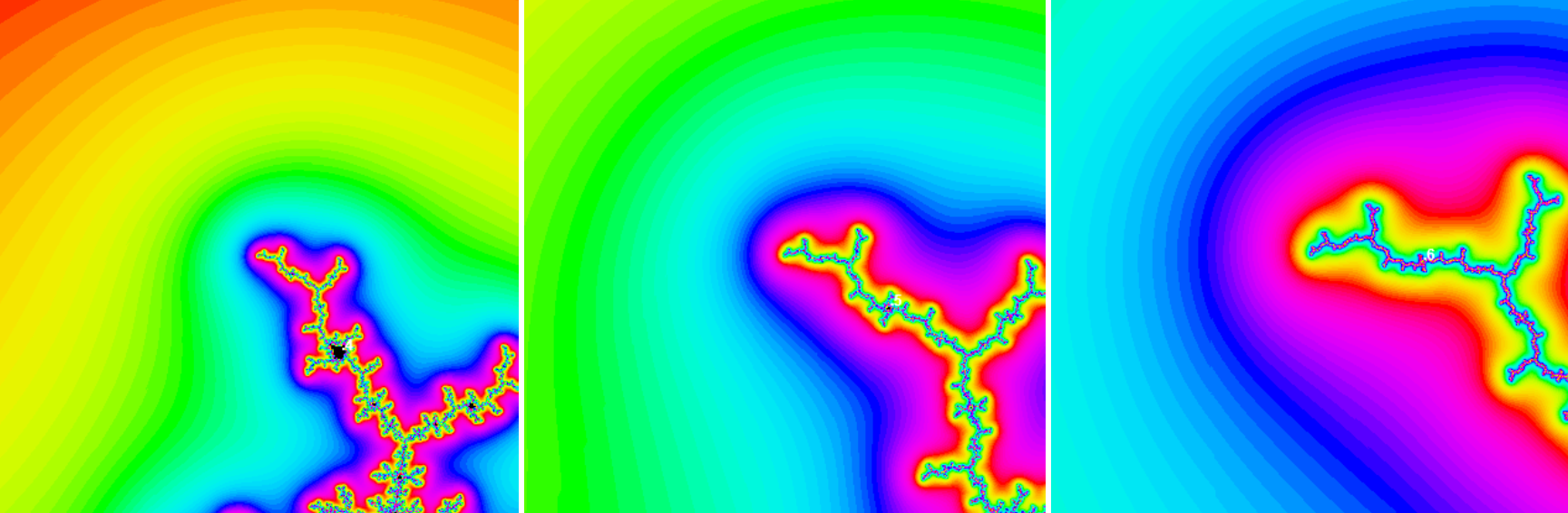

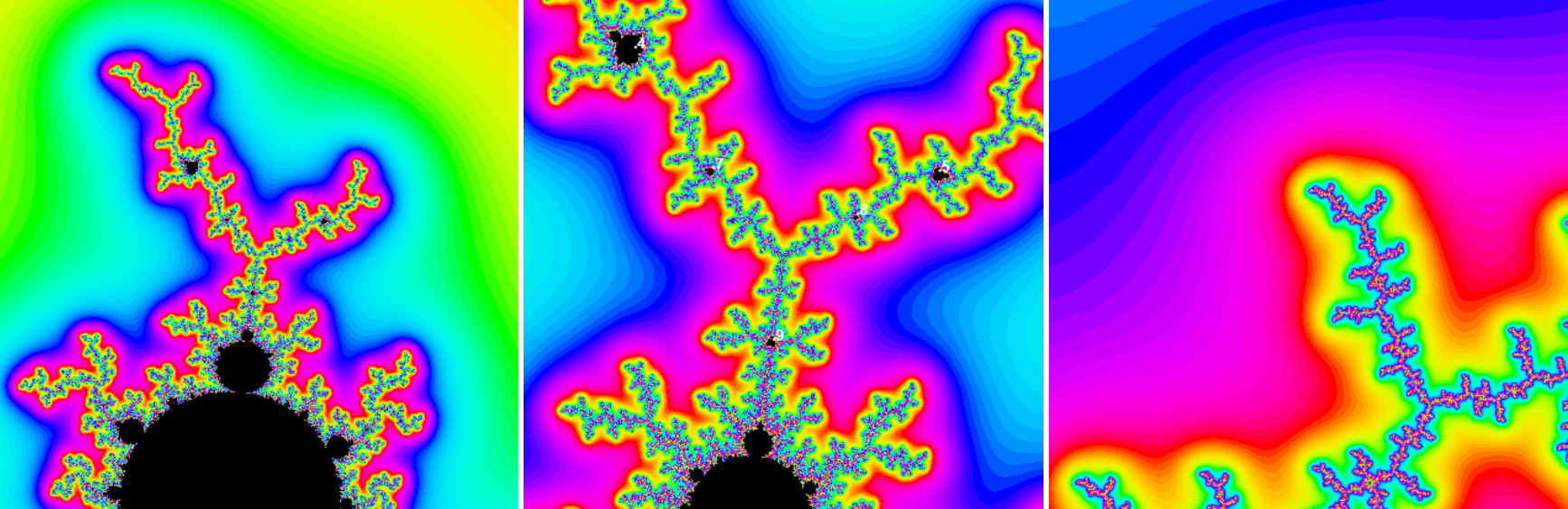

Here are illustrations of M near some of Misiurewicz points. Preperiodic points are in the center of the pictures. The images are zoomed 4, 3 and 1.3283 = 2.34 times respectevely. Some self-similar periodic points with its period are shown too.

In the last figures rotational angle is very close to 120o, which accounts for the 3-fold rotational symmetry in the picture. In the center of the picture one has 3 lines meeting, and there are numerous nearby points where 6 lines meet. At each of the letter points there is a tiny replica of M.

You see, that preperiodic points explain too spokes symmetry in the largest antenna attached to a primary bulb.

These pictures have next features in common:

- The preperiodic points are not in black regions of M.

- They exhibit self-similarity, i.e., they look roughly the same at shrinking the picture centered at preperiodic point by a factor of |λ| and rotating through the angle Arg(λ). This becomes more precise as the magnification increases. The rotational angles of the sequences are -23.1256o and 119.553o respectively. This accounts for the slight changes in orientation under successive magnifications in figures.

- There is a sequence of miniature Ms of decreasing size converging to the point. Each of them has a periodic point in its main cardioid (see the theorem below). When we shrink the picture by a factor of λ the miniature Ms shrink by a factor of λ2 therefore nearby miniature Ms shrink faster than the view window, so they eventually disappear.

- There is a fourth feature not visible in these pictures: For preperiodic point co , the Julia set J(co ) near the point z = co looks very much like the Mandelbrot set M near co . This is a theorem of Lei, which we will discuss on the next page.

Theorem Let co be a preperiodic point with period 1. Let cn denote the nearest periodic point with period n. Then as n approaches infinity

(cn - c0 )/(cn+1 - c0 ) → λ = 2h

where h is the fixed point of the critical orbit of co .

Proof: We will use Newton's approximation to find a root of an equation fCnon(0) = 0 for periodic point cn with period n near co . If (cn - co) value is small enough, then

fCnon(0) = fCo+(Cn-Co)on(0) = fCoon(0) + (cn - co) d/dc fCon(0) |C=Co = 0

(we do not prove that we can use this approximation). For simplicity we will denote

dn = d/dc fCon(0) |C=Co .

As co is preperiodic with period 1, than fCoon(0) = h for large enough n, therefore

cn - co = - h/dn .

Since fCo(n+1)(0) = [fCon(0)]2 + c, it follows that for large n

dn+1 = 2 h dn + 1

and

(cn - co )/(cn+1 - co ) = (h/dn)/(h/dn+1) = dn+1 /dn = 2h + 1/dn.

The limit of this as n approaches infinity is 2h as claimed, because dn gets arbitrarily large for large n.