4.6: Exponential and Logarithmic Equations

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Skills to Develop

- Use like bases to solve exponential equations.

- Use logarithms to solve exponential equations.

- Use the definition of a logarithm to solve logarithmic equations.

- Use the one-to-one property of logarithms to solve logarithmic equations.

- Solve applied problems involving exponential and logarithmic equations.

In 1859, an Australian landowner named Thomas Austin released 24 rabbits into the wild for hunting. Because Australia had few predators and ample food, the rabbit population exploded. In fewer than ten years, the rabbit population numbered in the millions.

Figure 4.6.1: Wild rabbits in Australia. The rabbit population grew so quickly in Australia that the event became known as the “rabbit plague.” (credit: Richard Taylor, Flickr)

Uncontrolled population growth, as in the wild rabbits in Australia, can be modeled with exponential functions. Equations resulting from those exponential functions can be solved to analyze and make predictions about exponential growth. In this section, we will learn techniques for solving exponential functions.

Using Like Bases to Solve Exponential Equations

The first technique involves two functions with like bases. Recall that the one-to-one property of exponential functions tells us that, for any real numbers b, S, and T, where b>0, b≠1, if bS=bT then S=T.

In other words, when an exponential equation has the same base on each side, the exponents must be equal. This also applies when the exponents are algebraic expressions. Therefore, we can solve many exponential equations by using the rules of exponents to rewrite each side as a power with the same base. Then, we use the fact that exponential functions are one-to-one to set the exponents equal to one another, and solve for the unknown.

For example, consider the equation 34x−7=32x3. To solve for x, we use the division property of exponents to rewrite the right side so that both sides have the common base, 3. Then we apply the one-to-one property of exponents by setting the exponents equal to one another and solving for x:

34x−7=32x334x−7=32x31Rewrite 3 as 3134x−7=32x−1Use the division property of exponents4x−7=2x−1Apply the one-to-one property of exponents2x=6Subtract 2x and add 7 to both sidesx=3Divide by 2

USING THE ONE-TO-ONE PROPERTY OF EXPONENTIAL FUNCTIONS TO SOLVE EXPONENTIAL EQUATIONS

For any algebraic expressions S and T, and any positive real number b≠1,

if bS=bT then S=T

![]() Given an exponential equation with the form bS=bT, where S and T are algebraic expressions with an unknown, solve for the unknown.

Given an exponential equation with the form bS=bT, where S and T are algebraic expressions with an unknown, solve for the unknown.

- Use the rules of exponents to simplify, if necessary, so that the resulting equation has the form bS=bT.

- Use the one-to-one property to set the exponents equal.

- Solve the resulting equation, S=T, for the unknown.

Example 4.6.1: Solving an Exponential Equation with a Common Base

Solve 2x−1=22x−4.

Solution

2x−1=22x−4The common base is 2x−1=2x−4By the one-to-one property the exponents must be equalx=3Solve for x

4.6.1

4.6.1

Solve 52x=53x+2.

- Answer

-

x=−2

Rewriting Equations So All Powers Have the Same Base

Sometimes the common base for an exponential equation is not explicitly shown. In these cases, we simply rewrite the terms in the equation as powers with a common base, and solve using the one-to-one property.

For example, consider the equation 256=4x−5. We can rewrite both sides of this equation as a power of 2. Then we apply the rules of exponents, along with the one-to-one property, to solve for x:

256=4x−528=(22)x−5The common base is 228=22x−10Rewrite each side as a power with base 28=2x−10Use the one-to-one property of exponents18=2xAdd 10 to both sidesx=9Divide by 2

Example 4.6.2: Solving Equations by Rewriting Them to Have a Common Base

Solve 8x+2=16x+1.

Solution

8x+2=16x+1(23)x+2=(24)x+1Write 8 and 16 as powers of 223x+6=24x+4To take a power of a power, multiply exponents3x+6=4x+4Use the one-to-one property to set the exponents equalx=2Solve for x

4.6.2

4.6.2

Solve 52x=253x+2.

- Answer

-

x=−1

Example 4.6.3: Solving Equations by Rewriting Roots with Fractional Exponents to Have a Common Base

Solve 25x=√2.

Solution

25x=21/2Write the square root of 2 as a power of 25x=12Use the one-to-one propertyx=110Solve for x

4.6.3

4.6.3

Solve 5x=√5.

- Answer

-

x=12

![]() : Do all exponential equations have a solution? If not, how can we tell if there is a solution during the problem-solving process?

: Do all exponential equations have a solution? If not, how can we tell if there is a solution during the problem-solving process?

No. Recall that the range of an exponential function is always positive. While solving the equation, we may obtain an expression that is undefined.

Example 4.6.4: Solving an Equation with Positive and Negative Powers

Solve 3x+1=−2.

Solution

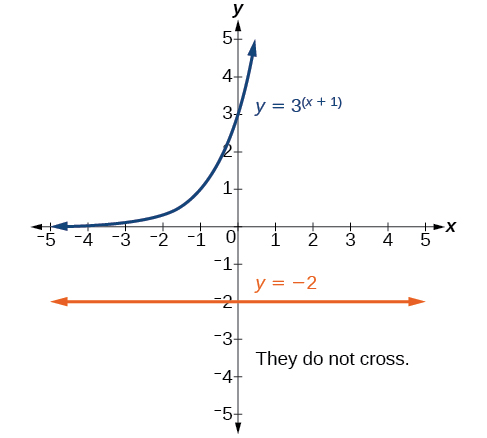

This equation has no solution. There is no real value of x that will make the equation a true statement because any power of a positive number is positive.

Analysis

Figure 4.6.2 shows that the two graphs do not cross so the left side is never equal to the right side. Thus the equation has no solution.

Figure 4.6.2

Solving Exponential Equations Using Logarithms

Sometimes the terms of an exponential equation cannot be rewritten with a common base. In these cases, we solve by taking the logarithm of each side.

![]() Given an exponential equation in which a common base cannot be found, solve for the unknown

Given an exponential equation in which a common base cannot be found, solve for the unknown

- Apply a logarithm function to both sides of the equation.

- If one of the terms in the equation has base 10, use the common logarithm.

- If none of the terms in the equation has base 10, use the natural logarithm.

- Use the rules of logarithms to solve for the unknown.

Example 4.6.5: Solving an Equation Containing Powers of Different Bases

Solve 5x+2=4x.

Solution

5x+2=4xThere is no easy way to get the powers to have the same baseln5x+2=ln4xTake ln of both sides(x+2)ln5=xln4Use laws of logsxln5+2ln5=xln4Use the distributive lawxln5−xln4=−2ln5Get terms containing x on one side, terms without x on the otherx(ln5−ln4)=−2ln5On the left hand side, factor out an xxln(54)=ln(125)Use the laws of logsx=ln(125)ln(54)Divide by the coefficient of x

Analysis

If we want a decimal approximation of this value, we can back up a little, and calculate −2ln5ln(54)≈−14.425.

4.6.4

4.6.4

Solve 2x=3x+1.

- Answer

-

x=ln3ln(23)

![]() : Is there any way to solve 2x=3x?

: Is there any way to solve 2x=3x?

Yes. The solution is x=0. Look at the graphs of y=2x and y=3x to see that they intersect only at x=0.

Equations Containing e

One common type of exponential equation uses the base e. This constant occurs again and again in nature, in mathematics, in science, in engineering, and in finance. When we have an equation with a base e on either side, we can use the natural logarithm to solve it.

![]() Given an equation of the form y=Aekt, solve for t.

Given an equation of the form y=Aekt, solve for t.

- Divide both sides of the equation by A.

- Apply the natural logarithm of both sides of the equation.

- Divide both sides of the equation by k.

Example 4.6.6: Solve an Equation of the Form y=Aekt

Solve 100=20e2t.

Solution

100=20e2t5=e2tDivide by the coefficient of e2tln5=2tTake ln of both sides. Use the fact that ln(x) and ex are inverse functionst=ln52Divide by the coefficient of t

Analysis

Using laws of logs, we can also write this answer in the form t=ln√5. If we want a decimal approximation of the answer, we can use a calculator to find ln52≈0.805.

4.6.5

4.6.5

Solve 3e0.5t=11.

- Answer

-

t=2ln(113) or ln(113)2

![]() : Does every equation of the form y=Aekt have a solution?

: Does every equation of the form y=Aekt have a solution?

No. There will be a solution when k≠0, or when y and A are either both 0 or neither 0, and they have the same sign. An example of an equation that has no solution is 2=−3et.

Example 4.6.7: Solving an Equation That Can Be Simplified to the Form y=Aekt

Solve 4e2x+5=12.

Solution

4e2x+5=124e2x=7Combine like termse2x=74Divide by the coefficient of e2x2x=ln(74)Take ln of both sidesx=12ln(74)≈0.280Solve for x

4.6.6

4.6.6

Solve 3+e2t=7e2t.

- Answer

-

t=ln(1√2)=−12ln(2)≈−0.347

Extraneous Solutions

Sometimes the methods used to solve an equation introduce an extraneous solution, which is a solution that is correct algebraically but does not satisfy the conditions of the original equation. One such situation may arise when a logarithm is taken on both sides of the equation. In such cases, remember that the argument of any logarithm must be positive. If the number we are evaluating in a logarithm function is negative, there is no output.

Example 4.6.8: Solving Exponential Functions in Quadratic Form

Solve e2x−ex=56.

Solution:

e2x−ex=56e2x−ex−56=0Get one side of the equation equal to zero(ex+7)(ex−8)=0Factor by the reverse FOIL methodex+7=0or ex−8=0If a product is zero, then one factor must be zeroex=−7or ex=8Isolate the exponentialsex=8Reject the equation in which the power equals a negative numberx=ln8Solve the equation in which the power equals a positive number

Analysis

When we plan to use factoring to solve a problem, we always get zero on one side of the equation, because zero has the unique property that when a product is zero, one or both of the factors must be zero. We reject the equation ex=−7 because a positive number never equals a negative number. The solution ln(−7) is not a real number, and in the real number system this solution is rejected as an extraneous solution.

4.6.7

4.6.7

Solve e2x=ex+2.

- Answer

-

x=ln2≈0.693

![]() : Does every logarithmic equation have a solution?

: Does every logarithmic equation have a solution?

No. Keep in mind that we can only apply the logarithm to a positive number. Always check for extraneous solutions.

Using the Definition of a Logarithm to Solve Logarithmic Equations

We have already seen that every logarithmic equation logb(x)=y is equivalent to the exponential equation by=x. We can use this fact, along with the rules of logarithms, to solve logarithmic equations where the argument is an algebraic expression.

For example, consider the equation log2(2)+log2(3x−5)=3. To solve this equation, we can use rules of logarithms to rewrite the left side in compact form and then apply the definition of logs to solve for x:

log2(2)+log2(3x−5)=3log2(2(3x−5))=3Apply the product rule of logarithmslog2(6x−10)=3Distribute23=6x−10Apply the definition of a logarithm8=6x−10Calculate 2318=6xAdd 10 to both sidesx=3Divide by 6

USING THE DEFINITION OF A LOGARITHM TO SOLVE LOGARITHMIC EQUATIONS

For any algebraic expression S and real numbers b and c,where b>0, b≠1,

logb(S)=c if and only if bc=S

Example 4.6.9: Using Algebra to Solve a Logarithmic Equation

Solve 2lnx+3=7.

Solution

2lnx+3=72lnx=4Subtract 3lnx=2Divide by 2x=e2≈7.389Rewrite in exponential form

4.6.8

4.6.8

Solve 6+lnx=10.

- Answer

-

x=e4≈54.598

Example 4.6.10: Using Algebra Before and After Using the Definition of the Natural Logarithm

Solve 2ln(6x)=7.

Solution:

2ln(6x)=7ln(6x)=72Divide by 26x=e7/2Use the definition of lnx=16e7/2≈5.519Divide by 6

4.6.9

4.6.9

Solve 2ln(x+1)=10.

- Answer

-

x=e5−1

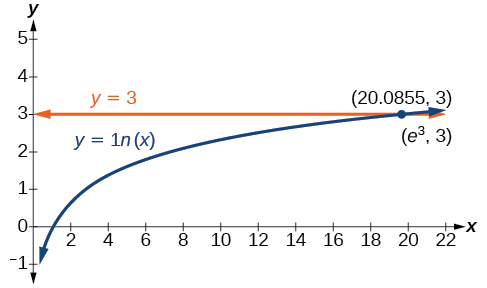

Example 4.6.11: Using a Graph to Understand the Solution to a Logarithmic Equation

Solve lnx=3.

Solution

lnx=3x=e3Use the definition of the natural logarithm

Figure 4.6.3 represents the graph of the equation. On the graph, the x-coordinate of the point at which the two graphs intersect is close to 20. In other words e3≈20. A calculator gives a better approximation: e3≈20.0855.

Figure 4.6.3: The graphs of y=lnx and y=3 cross at the point (e3,3), which is approximately (20.0855,3).

Using the One-to-One Property of Logarithms to Solve Logarithmic Equations

As with exponential equations, we can use the one-to-one property to solve logarithmic equations. The one-to-one property of logarithmic functions tells us that, for any real numbers x>0, S>0, T>0 and any positive real number b, where b≠1,

If logbS=logbT then S=T.

For example,

If log2(x−1)=log2(8), then x−1=8.

So, if x−1=8, then we can solve for x, and we get x=9. To check, we can substitute x=9 into the original equation: log2(9−1)=log2(8)=3. In other words, when a logarithmic equation has the same base on each side, the arguments must be equal. This also applies when the arguments are algebraic expressions. Therefore, when given an equation with logs of the same base on each side, we can use rules of logarithms to rewrite each side as a single logarithm. Then we use the fact that logarithmic functions are one-to-one to set the arguments equal to one another and solve for the unknown.

For example, consider the equation log(3x−2)−log(2)=log(x+4). To solve this equation, we can use the rules of logarithms to rewrite the left side as a single logarithm, and then apply the one-to-one property to solve for x:

log(3x−2)−log(2)=log(x+4)log(3x−22)=log(x+4)Apply the quotient rule of logarithms3x−22=x+4Apply the one to one property of a logarithm3x−2=2x+8Multiply both sides of the equation by 2x=10Subtract 2x and add 2

To check the result, substitute x=10 into log(3x−2)−log(2)=log(x+4).

log(3(10)−2)−log(2)=log((10)+4)log(28)−log(2)=log(14)log(282)=log(14)The solution checks

USING THE ONE-TO-ONE PROPERTY OF LOGARITHMS TO SOLVE LOGARITHMIC EQUATIONS

For any algebraic expressions S and T and any positive real number b, where b≠1,

If logbS=logbT then S=T

Note: when solving an equation involving logarithms, always check to see if the answer is correct or if it is an extraneous solution.

![]() Given an equation containing logarithms, solve it using the one-to-one property

Given an equation containing logarithms, solve it using the one-to-one property

- Use the rules of logarithms to combine like terms, if necessary, so that the resulting equation has the form logbS=logbT.

- Use the one-to-one property to set the arguments equal.

- Solve the resulting equation, S=T, for the unknown.

Example 4.6.12: Solving an Equation Using the One-to-One Property of Logarithms

Solve ln(x2)=ln(2x+3).

Solution

ln(x2)=ln(2x+3)x2=2x+3Use the one-to-one property of the logarithmx2−2x−3=0Get zero on one side before factoring(x−3)(x+1)=0Factor using FOILx−3=0or x+1=0 If a product is zero, one of the factors must be zerox=3orx=−1Solve for x

Analysis

There are two solutions: 3 or −1. The solution −1 is negative, but it checks when substituted into the original equation because the argument of the logarithm functions is still positive.

4.6.10

4.6.10

Solve ln(x2)=ln1.

- Answer

-

x=1 or x=−1

Solving Applied Problems Using Exponential and Logarithmic Equations

In previous sections, we learned the properties and rules for both exponential and logarithmic functions. We have seen that any exponential function can be written as a logarithmic function and vice versa. We have used exponents to solve logarithmic equations and logarithms to solve exponential equations. We are now ready to combine our skills to solve equations that model real-world situations, whether the unknown is in an exponent or in the argument of a logarithm.

One such application is in science, calculating the time it takes for half of the unstable material in a sample of a radioactive substance to decay, called its half-life. Table 4.6.1 lists the half-life for several of the more common radioactive substances.

| Substance | Use | Half-life |

|---|---|---|

| gallium-67 | nuclear medicine | 80 hours |

| cobalt-60 | manufacturing | 5.3 years |

| technetium-99m | nuclear medicine | 6 hours |

| americium-241 | construction | 432 years |

| carbon-14 | archeological dating | 5,715 years |

| uranium-235 | atomic power | 703,800,000 or 7.038×108 years |

We can see how widely the half-lives for these substances vary. Knowing the half-life of a substance allows us to calculate the amount remaining after a specified time. We can use the formula for radioactive decay:

A(t)=A0eln(0.5)tTA(t)=A0(eln(0.5))tTA(t)=A0(12)tT

where

- A0 is the amount initially present

- T is the half-life of the substance

- t is the time period over which the substance is studied

- y is the amount of the substance present after time t

Example 4.6.13: Using the Formula for Radioactive Decay to Find the Quantity of a Substance

How long will it take for ten percent of a 1000-gram sample of uranium-235 to decay?

Solution

y=1000eln(0.5)703,800,000t900=1000eln(0.5)703,800,000tAfter 10% decays, 900 grams are left0.9=eln(0.5)703,800,000tDivide by 1000ln(0.9)=ln(eln(0.5)703,800,000t)Take ln of both sidesln(0.9)=ln(0.5)703,800,000tln(eM)=Mt=703,800,000×ln(0.9)ln(0.5)Solve for tt≈106,979,777years

Analysis

Ten percent of 1000 grams is 100 grams. If 100 grams decay, the amount of uranium-235 remaining is 900 grams.

4.6.11

4.6.11

How long will it take before twenty percent of our 1000-gram sample of uranium-235 has decayed?

- Answer

-

t=703,800,000×ln(0.8)ln(0.5)years ≈ 226,572,993 years.

Media

Access these online resources for additional instruction and practice with exponential and logarithmic equations.

Key Equations

| One-to-one property for exponential functions | For any algebraic expressions S and T and any positive real number b, where if bS=bT then S=T. |

| Definition of a logarithm | For any algebraic expression S and positive real numbers b and c, where b≠1, logb(S)=c if and only if bc=S. |

| One-to-one property for logarithmic functions | For any algebraic expressions S and T and any positive real number b, where b≠1, if logbS=logbT then S=T. |

Key Concepts

- We can solve many exponential equations by using the rules of exponents to rewrite each side as a power with the same base. Then we use the fact that exponential functions are one-to-one to set the exponents equal to one another and solve for the unknown.

- When we are given an exponential equation where the bases are explicitly shown as being equal, set the exponents equal to one another and solve for the unknown. See Example 4.6.1.

- When we are given an exponential equation where the bases are not explicitly shown as being equal, rewrite each side of the equation as powers of the same base, then set the exponents equal to one another and solve for the unknown. See Example 4.6.2, Example 4.6.3, and Example 4.6.4.

- When an exponential equation cannot be rewritten with a common base, solve by taking the logarithm of each side. See Example 4.6.5.

- We can solve exponential equations with base e,by applying the natural logarithm of both sides because exponential and logarithmic functions are inverses of each other. See Example 4.6.6 and Example 4.6.7.

- After solving an exponential equation, check each solution in the original equation to find and eliminate any extraneous solutions. See Example 4.6.8.

- When given an equation of the form logb(S)=c, where S is an algebraic expression, we can use the definition of a logarithm to rewrite the equation as the equivalent exponential equation bc=S, and solve for the unknown. See Example 4.6.9 and Example 4.6.10.

- We can also use graphing to solve equations with the form logb(S)=c. We graph both equations y=logb(S) and y=c on the same coordinate plane and identify the solution as the x-value of the intersecting point. See Example 4.6.11.

- When given an equation of the form logbS=logbT, where S and T are algebraic expressions, we can use the one-to-one property of logarithms to solve the equation S=T for the unknown. See Example 4.6.12.

- Combining the skills learned in this and previous sections, we can solve equations that model real world situations, whether the unknown is in an exponent or in the argument of a logarithm. See Example 4.6.13.

Contributors

- Lynn Marecek (Santa Ana College) and MaryAnne Anthony-Smith (formerly of Santa Ana College). This content produced by OpenStax and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license.