6.1: Simplify Expressions with Square Roots

- Page ID

- 66344

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Simplify expressions with roots

- Estimate and approximate roots

- Simplify variable expressions with roots

Before you get started, take this readiness quiz.

1. Simplify

a. \((−9)^{2}\)

b. \(-9^{2}\)

2. Round \(3.846\) to the nearest hundredth.

3. Simplify

a. \(x^{3} \cdot x^{3}\)

b. \(y^{2} \cdot y^{2}\)

Simplify Expressions with Roots

In Foundations, we briefly looked at square roots. Remember that when a real number \(n\) is multiplied by itself, we write \(n^{2}\) and read it '\(n\) squared’. This number is called the square of \(n\), and \(n\) is called the square root. For example,

\(13^{2}\) is read "\(13\) squared"

\(169\) is called the square of \(13\), since \(13^{2}=169\)

\(13\) is a square root of \(169\)

Square

If \(n^{2}=m\), then \(m\) is the square of \(n\).

Square Root

If \(n^{2}=m\), then \(n\) is a square root of \(m\).

Notice \((−13)^{2} = 169\) also, so \(−13\) is also a square root of \(169\). Therefore, both \(13\) and \(−13\) are square roots of \(169\).

So, every positive number has two square roots—one positive and one negative. What if we only wanted the positive square root of a positive number? We use a radical sign, and write, \(\sqrt{m}\), which denotes the positive square root of \(m\). The positive square root is also called the principal square root.

We also use the radical sign for the square root of zero. Because \(0^{2}=0, \sqrt{0}=0\). Notice that zero has only one square root.

\(\sqrt{m}\) is read "the square root of \(m\)."

If \(n^{2}=m\), then \(n=\sqrt{m}\), for \(n\geq 0\).

We know that every positive number has two square roots and the radical sign indicates the positive one. We write \(\sqrt{169}=13\). If we want to find the negative square root of a number, we place a negative in front of the radical sign. For example, \(-\sqrt{169}=-13\).

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{144}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{289}\)

- Solution

-

a.

\(\sqrt{144}\)

Since \(12^{2}=144\), and \(12\geq 0\)

\(12\)

b.

\(-\sqrt{289}\)

Since \(17^{2}=289\), \(17\geq 0\), and the negative is in front of the radical sign.

\(-17\)

Simplify:

a. \(-\sqrt{64}\)

b. \(\sqrt{225}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(-8\)

b. \(15\)

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{100}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{121}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(10\)

b. \(-11\)

Can we simplify \(\sqrt{-49}\)? Is there a number whose square is \(-49\)?

\((\)___\( )^{2}=-49\)

Any positive number squared is positive. Any negative number squared is positive. There is no real number equal to \(\sqrt{-49}\). The square root of a negative number is not a real number.

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{-196}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{64}\)

- Solution

-

a.

\(\sqrt{-196}\)

There is no real number whose square is \(-196\).

\(\sqrt{-196}\) is not a real number.

b.

\(-\sqrt{64}\)

The negative is in front of the radical.

\(-8\)

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{-169}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{81}\)

- Answer

-

a. not a real number

b. \(-9\)

Simplify:

a. \(-\sqrt{49}\)

b. \(\sqrt{-121}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(-7\)

b. not a real number

Properties of \(\sqrt{a}\)

When

- \(a \geq 0\), then \(\sqrt{a}\) is a real number.

- \(a<0\), then \(\sqrt{a}\) is not a real number.

Simplify Variable Expressions with Square Roots

Note, for example,

\[\sqrt{4^2}=\sqrt{16}=4\nonumber\]

but,

\[\sqrt{(-4)^2}=\sqrt{16}=4,\nonumber\]

So that the result is positive.

How can we make sure the square root of \(−5\) squared is \(5\)? We can use the absolute value. \(|−5|=5\): \[\sqrt{a^{2}}=|a|.\] This guarantees the principal root is positive.

We have

\(\sqrt{a^{2}}=|a|\)

Simplify \(\sqrt{x^{2}}\).

- Solution

-

We use the absolute value to be sure to get the positive root.

\(\sqrt{x^{2}}=|x|\)

Simplify \(\sqrt{b^{2}}\).

- Answer

-

\(|b|\)

What about square roots of higher powers of variables? The power property of exponents says \(\left(a^{m}\right)^{n}=a^{m \cdot n}\). So if we square \(a^{m}\), the exponent will become \(2m\).

\(\left(a^{m}\right)^{2}=a^{2 m}\)

Looking now at the square root.

\(\sqrt{a^{2 m}}=\sqrt{\left(a^{m}\right)^{2}}\)

Since \(2\) is even, \(\sqrt[2]{x^{2}}=|x|\). So

\[\sqrt{a^{2 m}}=\left|a^{m}\right|.\]

We apply this concept in the next example.

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{x^{6}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{y^{16}}\)

- Solution

-

a.

\(\sqrt{x^{6}}\)

Since \(\left(x^{3}\right)^{2}=x^{6}\), this is equal to

\(\sqrt{\left(x^{3}\right)^{2}}.\)

Since \(\sqrt{a^{2}}=|a|\), this is equal to

\(\left|x^{3}\right|\)

b.

\(\sqrt{y^{16}}\)

Since \(\left(y^{8}\right)^{2}=y^{16}\), this is equal to

\(\sqrt{\left(y^{8}\right)^{2}}.\)

Since \(\sqrt{a^{2}}=|a|\), this is equal to

\(y^{8}\)

In this case the absolute value sign is not needed as \(y^{8}\) is positive.

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{y^{18}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{z^{12}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(|y^{9}|\)

b. \(z^{6}\)

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{m^{4}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{b^{10}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(m^{2}\)

b. \(|b^{5}|\)

In the next example, we now have a coefficient in front of the variable. The concept \(\sqrt{a^{2 m}}=\left|a^{m}\right|\) works in much the same way.

\(\sqrt{16 r^{22}}=4\left|r^{11}\right|\) because \(\left(4 r^{11}\right)^{2}=16 r^{22}\).

But notice \(\sqrt{25 u^{8}}=5 u^{4}\) and no absolute value sign is needed as \(u^{4}\) is always non-negative.

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{16 n^{2}}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{81 c^{2}}\)

- Solution

-

a.

\(\sqrt{16 n^{2}}\)

Since \((4 n)^{2}=16 n^{2}\), this is equal to

\(\sqrt{(4 n)^{2}}.\)

Since \(\sqrt{a^{2}}=|a|\), this is equal to

\(4|n|.\)

b.

\(-\sqrt{81 c^{2}}\)

Since \((9 c)^{2}=81 c^{2}\), this is equal to

\(-\sqrt{(9 c)^{2}}.\)

Since \(\sqrt{a^{2}}=|a|\), this is then equal to

\(-9|c|.\)

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{64 x^{2}}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{100 p^{2}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(8|x|\)

b. \(-10|p|\)

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{169 y^{2}}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{121 y^{2}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(13|y|\)

b. \(-11|y|\)

The next examples have two variables.

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{36 x^{2} y^{2}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{121 a^{6} b^{8}}\)

- Solution

-

a.

\(\sqrt{36 x^{2} y^{2}}\)

Since \((6 x y)^{2}=36 x^{2} y^{2}\)

\(\sqrt{(6 x y)^{2}}\)

Take the square root.

\(6|xy|\)

b.

\(\sqrt{121 a^{6} b^{8}}\)

Since \(\left(11 a^{3} b^{4}\right)^{2}=121 a^{6} b^{8}\)

\(\sqrt{\left(11 a^{3} b^{4}\right)^{2}}\)

Take the square root.

\(11\left|a^{3}\right| b^{4}\)

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{100 a^{2} b^{2}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{144 p^{12} q^{20}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(10|ab|\)

b. \(12p^{6}q^{10}\)

Simplify:

a. \(\sqrt{225 m^{2} n^{2}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{169 x^{10} y^{14}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(15|mn|\)

b. \(13\left|x^{5} y^{7}\right|\)

Key Concepts

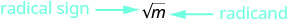

- Square Root Notation

- \(\sqrt{m}\) is read ‘the square root of \(m\)’

- If \(n^{2}=m\), then \(n=\sqrt{m}\), for \(n≥0\).

Figure 8.1.1 - The square root of \(m\), \(\sqrt{m}\), is a positive number whose square is \(m\).

- Properties of \(\sqrt{a}\)

- \(a≥0\), then \(\sqrt{a}\) is a real number

- \(a<0\), then \(\sqrt{a}\) is not a real number

- Simplifying Odd and Even Roots

- \(\sqrt{a^{2}}=|a|\). We must use the absolute value signs when we take a square root of an expression with a variable in the radical.

Glossary

- square of a number

- If \(n^{2}=m\), then \(m\) is the square of \(n\).

- square root of a number

- If \(n^{2}=m\), then \(n\) is a square root of \(m\).

Practice makes perfect

Simplifying Expressions with Roots

In the following exercises, simplify.

1. a. \(\sqrt{64}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{81}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(8\)

b. \(-9\)

2. a. \(\sqrt{169}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{100}\)

3. a. \(\sqrt{196}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{1}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(14\)

b. \(-1\)

4. a. \(\sqrt{144}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{121}\)

5. a. \(\sqrt{\dfrac{4}{9}}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{0.01}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(\dfrac{2}{3}\)

b. \(-0.1\)

6. a. \(\sqrt{\dfrac{64}{121}}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{0.16}\)

7. a. \(\sqrt{-121}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{289}\)

- Answer

-

a. not a real number

b. \(-17\)

8. a. \(-\sqrt{400}\)

b. \(\sqrt{-36}\)

9. a. \(-\sqrt{225}\)

b. \(\sqrt{-9}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(-15\)

b. not a real number

10. a. \(\sqrt{-49}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{256}\)

11. \(\sqrt{70}\)

- Answer

-

\(8<\sqrt{70}<9\)

12. \(\sqrt{55}\)

13. \(\sqrt{200}\)

- Answer

-

\(14<\sqrt{200}<15\)

14. \(\sqrt{172}\)

In the following exercises, approximate each root and round to two decimal places.

15. \(\sqrt{19}\)

- Answer

-

\(\approx 4.36\)

16. \(\sqrt{21}\)

17. \(\sqrt{53}\)

- Answer

-

\(\approx 7.28\)

18. \(\sqrt{47}\)

Simplify Variable Expressions with Roots

In the following exercises, simplify using absolute values as necessary.

19. a. \(\sqrt{x^{6}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{y^{16}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(|x^{3}|\)

b. \(y^{8}\)

20. a. \(\sqrt{a^{14}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{w^{24}}\)

21. a. \(\sqrt{x^{24}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{y^{22}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(x^{12}\)

b. \(|y^{11}|\)

22. a. \(\sqrt{a^{12}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{b^{26}}\)

23. a. \(\sqrt{49 x^{2}}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{81 x^{18}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(7|x|\)

b. \(-9|x^{9}|\)

24. a. \(\sqrt{100 y^{2}}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{100 m^{32}}\)

25. a. \(\sqrt{121 m^{20}}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{64 a^{2}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(11m^{10}\)

b. \(-8|a|\)

26. a. \(\sqrt{81 x^{36}}\)

b. \(-\sqrt{25 x^{2}}\)

27. a. \(\sqrt[4]{16 x^{8}}\)

b. \(\sqrt[6]{64 y^{12}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(2x^{2}\)

b. \(2y^{2}\)

28. a. \(\sqrt{144 x^{2} y^{2}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{169 w^{8} y^{10}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(12|x y|\)

b. \(13 w^{4}\left|y^{5}\right|\)

29. a. \(\sqrt{196 a^{2} b^{2}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{81 p^{24} q^{6}}\)

30. a. \(\sqrt{121 a^{2} b^{2}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{9 c^{8} d^{12}}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(11|ab|\)

b. \(3c^{4}d^{6}\)

31. a. \(\sqrt{225 x^{2} y^{2} z^{2}}\)

b. \(\sqrt{36 r^{6} s^{20}}\)

Writing Exercises

32. Why is there no real number equal to \(\sqrt{-64}\)?

- Answer

-

Since the square of any real number is positive, it's not possible for a real number to square to \(-64\).

33. What is the difference between \(9^{2}\) and \(\sqrt{9}\)?

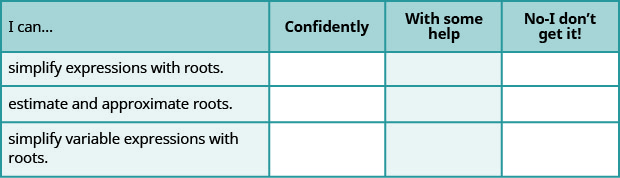

Self Check

a. After completing the exercises, use this checklist to evaluate your mastery of the objectives of this section.

b. If most of your checks were:

…confidently. Congratulations! You have achieved the objectives in this section. Reflect on the study skills you used so that you can continue to use them. What did you do to become confident of your ability to do these things? Be specific.

…with some help. This must be addressed quickly because topics you do not master become potholes in your road to success. In math every topic builds upon previous work. It is important to make sure you have a strong foundation before you move on. Who can you ask for help? Your fellow classmates and instructor are good resources. Is there a place on campus where math tutors are available? Can your study skills be improved?

…no - I don’t get it! This is a warning sign and you must not ignore it. You should get help right away or you will quickly be overwhelmed. See your instructor as soon as you can to discuss your situation. Together you can come up with a plan to get you the help you need.