Section 3.2: Absolute Value Equations

- Page ID

- 192822

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)We will rely heavily on these skills throughout this section.

- Solve \(x+3=7\) for \(x\)

- Solve \(3y-2x-1=5-2y+x\) for \(y\)

- Graph the lines \(y=x+3\) and \(y=7\) and determine the point of their intersection

Motivating Problem

You’re using GPS to find out how far you are from a coffee shop. Whether you're two blocks east or two blocks west, the distance is still 2. If the total walking distance is six blocks, how far could you be from the shop?

Fun Fact

Absolute value equations are used in real life to define tolerances—for example, a machine part must be within \(\pm 0.01\) inches of a target measurement. It’s all about how far off from an error of zero you’re allowed to be!

The Goal

In this section, we’ll learn to solve absolute value equations both algebraically and graphically. We’ll explore what it means to say “distance equals a number” and use Desmos to visualize where two expressions intersect.

Solve Absolute Value Equations

As we prepare to solve absolute value equations, we review our definition of absolute value.

The absolute value of a number is its distance from zero on the number line.

The absolute value of a number n is written as \(|n|\) and \(|n|\geq 0\) for all numbers.

Absolute values are always greater than or equal to zero.

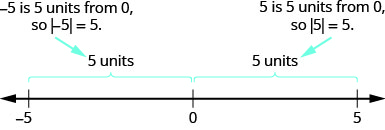

We learned that both a number and its opposite are the same distance from zero on the number line. Since they have the same distance from zero, they have the same absolute value. For example:

- \(-5\) is 5 units away from 0, so \(|-5|=5\).

- \(5\) is 5 units away from 0, so \(|5|=5\).

For the equation |x|=5,|x|=5, we are looking for all numbers that make this a true statement. We are looking for the numbers whose distance from zero is 5. We just saw that both 5 and -5-5 are five units from zero on the number line. They are the solutions to the equation.

\(\begin{array} {ll} {\text{If}} &{|x|=5} \\ {\text{then}} &{x=-5\text{ or }x=5} \\ \end{array}\)

Let's visualize this graphically. Consider the graphs of \(y=|x|\) and \(y=5\). The equation \(|x|=5\) has a solution corresponding to each point of intersection on the graph. We can see from the graph that the intersection points occur when \(x=-5\) and \(x=5\).

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=426&height=284)

The solution can be simplified to a single statement by writing \(x=\pm 5\). This is read, “x is equal to positive or negative 5”.

We can generalize this to the following property for absolute value equations.

For any algebraic expression, u, and any positive real number, a,

\[\begin{array} {ll} {\text{if}} &{|u|=a} \\ {\text{then}} &{u=-a \text{ or }u=a} \\ \nonumber \end{array}\]

Remember that an absolute value cannot be a negative number.

Solve each equation graphically:

- \(|x|=8\)

- \(|x|=-6\)

- \(|x|=0\)

Solution

a. The graph of \(y=|x|\) intersects the graph of \(y=8\) twice.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=443&height=295)

\(\begin{array} {ll} {} &{|x|=8} \\ {\text{Write the equivalent equations.}} &{x=-8 \text{ or } x=8} \\ {} &{x=\pm 8} \\ \end{array}\)

b. The graph of \(y=|x|\) never intersects the graph of \(y=-6\) since an absolute value is always positive. Therefore, there are no solutions to this equation.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=443&height=295)

\(\begin{array} {ll} {} &{|x|=-6} \\ {} &{\text{No solution}} \\ \end{array}\)

c. The graph of \(y=|x|\) intersects the graph of \(y=0\) (the \(x\)-axis) exactly once.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=433&height=288)

\(\begin{array} {ll} {} &{|x|=0} \\ {\text{Write the equivalent equations.}} &{x=-0\text{ or }x=0} \\ {\text{Since }-0=0,} &{x=0} \\ \end{array}\)

Both equations tell us that \(x=0\), and so there is only one solution.

Solve each equation graphically:

- \(|x|=2\)

- \(|x|=-4\)

- \(|x|=0\)

- Answers

-

- \(\pm 2\)

- no solution

- 0

To solve an absolute value equation, we first isolate the absolute value expression using the same procedures we used to solve linear equations. Once we isolate the absolute value expression, we rewrite it as the two equivalent equations.

How to Solve Absolute Value Equations

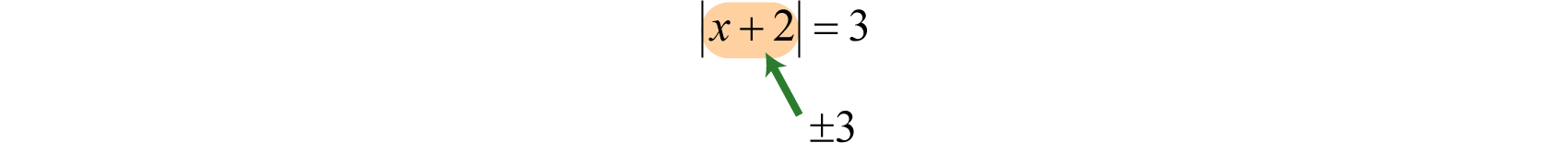

Solve: \(|x+2|=3\).

Solution

We begin by solving the equation algebraically. In this case, the argument "inside" of the absolute value is \(x+2\) and must be equal to \(3\) or \(−3\).

Therefore, to solve this absolute value equation, set \(x+2\) equal to \(±3\) and solve each linear equation as usual.

\(\begin{array} { c } { | x + 2 | = 3 } \\ { x + 2 = - 3 \quad \quad\text { or } \quad\quad x + 2 = 3 } \\ { x = - 5 \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad x = 1 } \end{array}\)

To visualize these solutions, graph the relations on the same set of coordinate axes and find where they intersect.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=477&height=318)

From the graph, we can see the points of intersection occur when \(x = −5\) and \(x = 1\).

Solution Check...

| Check \(x=-5\) | Check \(x=1\) |

| \(\begin{aligned} |x + 2| &\overset{?}{=} 3 \\ \left| {\color{Cerulean}{-5}} + 2 \right| &\overset{?}{=} 3 \\ | -3 | &\overset{?}{=} 3 \\ 3 &= 3 \checkmark \end{aligned}\) |

\(\begin{aligned} |x + 2| &\overset{?}{=} 3 \\ \left| {\color{Cerulean}{1}} + 2 \right| &\overset{?}{=} 3 \\ |3| &\overset{?}{=} 3 \\ 3 &= 3 \checkmark \end{aligned}\) |

Solve: \(| 2 x + 3 | = 4\).

- Answer

-

The solutions are \(x=-\frac{7}{2}\) and \(x=\frac{1}{2}\)

The steps for solving an absolute value equation are summarized here.

- Isolate the absolute value expression.

- Write the equivalent equations.

- Solve each equation.

- Check each solution.

Solve \(2|x-7|+5=9\).

- Solution

- \(\begin{array}{c}2|x - 7| + 5 = 9 \\2|x-7|=4\\|x - 7| = 2 \\x - 7 = -2 \quad\quad\text{or}\quad\quad x - 7 = 2 \\x = 5 \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad x = 9\end{array}\)

-

Check \(x=5\) Check \(x=9\) \(\begin{aligned}

2|x - 7| + 5 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\

2\left|{\color{Cerulean}{5}} - 7\right| + 5 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\

2|{-2}| + 5 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\

2(2) + 5 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\

4 + 5 &= 9 \checkmark

\end{aligned}\)\(\begin{aligned}

2|x - 7| + 5 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\

2\left|{\color{Cerulean}{9}} - 7\right| + 5 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\

2|2| + 5 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\

2(2) + 5 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\

4 + 5 &= 9 \checkmark

\end{aligned}\)

Solve: \(3|x-4|-4=8\).

- Answer

-

\(x=8,\space x=0\)

Solve: \(2 |5x − 1| − 3 = 9\).

Solution

\(\begin{array}{c}2|5x - 1| - 3 = 9 \\2|5x-1|=12\\|5x - 1| = 6 \\5x - 1 = -6 \quad\quad\text{or}\quad\quad 5x - 1 = 6 \\5x = -5 \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad 5x = 7 \\x = -1 \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad x = \dfrac{7}{5}\end{array}\)

| Check \(x=-1\) | Check \(x=\frac{7}{5}\) |

| \(\begin{aligned} 2|5x - 1| - 3 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\ 2\left|5({\color{Cerulean}{-1}}) - 1\right| - 3 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\ 2|-5 - 1| - 3 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\ 2|{-6}| - 3 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\ 2(6) - 3 &= 9 \\ 12 - 3 &= 9 \checkmark\end{aligned}\) |

\\(\begin{aligned} 2|5x - 1| - 3 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\ 2\left|5\left({\color{Cerulean}{\dfrac{7}{5}}}\right) - 1\right| - 3 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\ 2|7 - 1| - 3 &\overset{?}{=} 9 \\ 2(6) - 3 &= 9 \\ 12 - 3 &= 9 \checkmark \end{aligned}\) |

Remember, an absolute value is always positive!

Solve: \(|\frac{3}{4}x-5|+9=4\).

- Answer

-

No solution

Solve: \(| 7 x - 6 | + 3 = 3\).

Solution

\(\begin{array}{c}

|7x - 6| + 3 = 3 \\

|7x - 6| = 0 \\

7x - 6 = 0 \\

7x = 6 \\

x = \dfrac{6}{7}

\end{array}\)

Geometrically, we can see that the single intersection corresponds to the only solution.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=540&height=360)

Solve \(9+|7x+1|=9\)

- Answer

-

\(x=-\dfrac{1}{7}\)

Some of our absolute value equations could be of the form \(|u|=|v|\) where u and v are algebraic expressions. For example, \(|x-3|=|2x+1|\).

How would we solve them? If two algebraic expressions are equal in absolute value, then they are either equal to each other or negatives of each other. The property for absolute value equations says that for any algebraic expression, u, and a positive real number, a, if \(|u|=a\), then \(u=-a\) or \(u=a\).

This tells us that

\(\begin{array} {llll}

{\text{if}} &{|u|=|v|} &{} &{}

\\ {\text{then}} &{|u|=v} &{\text{or}} &{|u|=-v}

\\ {\text{and so}} &{u=v \text{ or } u = -v} &{\text{or}} &{u=-v \text{ or } u = -(-v)}

\\ \end{array}\)

This leads us to the following property for equations with two absolute values.

For any algebraic expressions, u and v,

\[\begin{array} {ll} {\text{if}} &{|u|=|v|} \\ {\text{then}} &{u=-v\text{ or }u=v} \\ \nonumber \end{array}\]

When we take the opposite of a quantity, we must be careful with the signs and add parentheses where needed.

Solve: \(|5x-1|=|2x+3|\).

- Solution

-

\(\begin{array} {ll} {} &{} &{|5x-1|=|2x+3|} &{} \\ {} &{} &{} &{} \\ {\text{Write the equivalent equations.}} &{5x-1=-(2x+3)} &{\text{or}} &{5x-1=2x+3} \\ {} &{5x-1=-2x-3} &{\text{or}} &{3x-1=3} \\ {\text{Solve each equation.}} &{7x-1=-3} &{} &{3x=4} \\ {} &{7x=-2} &{} &{x=\frac{4}{3}} \\ {} &{x=-\frac{2}{7}} &{\text{or}} &{x=\frac{4}{3}} \\ {\text{Check.}} &{} &{} &{} \\ {\text{We leave the check to you.}} &{} &{} &{} \\ \end{array}\)

Solve: \(|7x-3|=|3x+7|\).

- Answer

-

\(x=-\frac{2}{5}, \space x=\frac{5}{2}\)