Section 1.4: Integers

- Page ID

- 182860

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)We will rely heavily on these skills throughout this section.

- Plot 0, 2, and 5 on a number line

- Fill in the appropriate symbol \(=\), \(<\), or \(>\): \(2\)_____\(5\)

- Simplify \(3+4-5\)

- Simplify \(\sqrt{144}\)

Motivating Problem

You check your bank account and see that you have $15. Then you accidentally use your debit card to buy a $25 pair of shoes. What does your account balance show now? How can a number be less than zero, and what does that mean?

Fun Fact

Although ancient Chinese and Indian mathematicians employed negative numbers for trade and accounting, Europeans only began accepting them during the Renaissance. Today, negative numbers are used in everything from banking to data science.

The Goal

In this section, we will discover that numbers don’t stop at zero. We'll explore the world of positive and negative integers and learn how to add, subtract, multiply, and divide them. With the help of number lines and real-life examples like temperatures and money, we will understand opposites, absolute value, and how to make sense of operations with signed numbers.

Simplify Expressions with Absolute Value

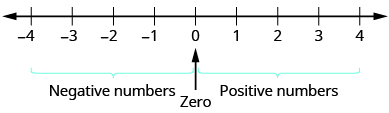

A negative number is a number less than 0. The negative numbers are to the left of zero on the number line below.

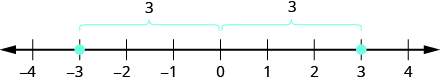

You may have noticed that, on the number line, the negative numbers are a mirror image of the positive numbers, with zero in the middle. Because the numbers \(2\) and \(−2\) are the same distance from zero, each one is called the opposite of the other. The opposite of \(2\) is \(−2\), and the opposite of \(−2\) is \(2\).

The opposite of a number is the number that is the same distance from zero on the number line but on the opposite side of zero.

The opposite of 3 is \(−3\).

\[ \begin{align*} & -a \text{ means the opposite of the number } a \\ & \text{The notation } -a \text{ is read as “the opposite of } a \text{.”} \end{align*} \]

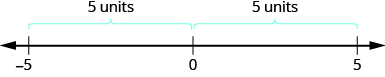

We saw that numbers such as 3 and −3 are opposites because they are the same distance from 0 on the number line. They are both three units from 0. The distance between 0 and any number on the number line is called the absolute value of that number.

The absolute value of a number is its distance from 0 on the number line.

The absolute value of a number \(n\) is written as \(|n|\) and \(|n|≥0\) for all numbers.

Absolute values are always greater than or equal to zero.

For example,

\[\begin{align*} & -5 \text{ is } 5 \text{ units away from 0, so } |-5|=5. \\ & 5 \text{ is }5\text{ units away from 0, so }|5|=5. \end{align*}\]

The Figure below illustrates this idea.

The absolute value of a number is never negative because distance cannot be negative. The only number with absolute value equal to zero is the number zero itself because the distance from 0 to 0 on the number line is zero units.

In the next example, we’ll order expressions with absolute values.

Fill in \(<,\,>,\) or \(=\) for each of the following pairs of numbers:

- \(\mathrm{|−5|}\_\_\_\_\mathrm{−|−5|}\)

- \(\mathrm{8}\_\_\_\_\mathrm{−|8|}\)

- \(\mathrm{−9}\_\_\_\_\mathrm{−|−9|}\)

- \(\mathrm{-(-16)}\_\_\_\_\mathrm{−|-16|}\)

Solution

a.

\(\begin{array}{lrcc} { \text{ } \\ \text{Simplify.} \\ \text{Order.} \\ \text{ } } & {|−5| \\ 5 \\ 5 \\ |−5|} & {\_\_ \\ \_\_ \\ > \\ >} & {−|−5| \\ −5 \\ −5 \\ −|−5|} \end{array}\)

b.

\(\begin{array}{llcc} { \text{ } \\ \text{Simplify.} \\ \text{Order.} \\ \text{ } } & {8 \\ 8 \\ 8 \\ 8} & {\_\_ \\ \_\_ \\ > \\ >} & {−|−8| \\ −8 \\ −8 \\ −|−8|} \end{array}\)

c.

\(\begin{array}{lrcc} { \text{ } \\ \text{Simplify.} \\ \text{Order.} \\ \text{ } } & {−9 \\ −9 \\ −9 \\ −9} & {\_\_ \\ \_\_ \\ = \\ =} & {−|−9| \\ −9 \\ −9 \\ −|−9|} \end{array}\)

d.

\(\begin{array}{lrcc} { \text{ } \\ \text{Simplify.} \\ \text{Order.} \\ \text{ } } & {−(−16) \\ 16 \\ 16 \\ −(−16)} & {\_\_ \\ \_\_ \\ = \\ =} & {−|−16| \\ 16 \\ 16 \\ |−16|} \end{array}\)

Fill in \(<,\,>,\) or \(=\) for each of the following pairs of numbers:

a. \(−|−10|\_\_−10\)

b. \(2 \_\_−|−2|\)

c. \(−8 \_\_|−8|\)

d. \(−(−9) \_\_|−9|.\)

- Answer

-

a. \(=\)

b. \(>\)

c. \(<\)

d. \(=\)

We now add absolute value bars to our list of grouping symbols. When we use the order of operations, first we simplify inside the absolute value bars as much as possible, then we take the absolute value of the resulting number.

\[\begin{array}{lclc} \text{Parentheses} & () & \text{Braces} & \{ \} \\ \text{Brackets} & [] & \text{Absolute value} & ||\end{array}\nonumber\]

In the next example, we simplify the expressions inside absolute value bars first just like we do with parentheses.

Simplify: \(\mathrm{24−|19−3(6−2)|}\).

Solution

\(\begin{array}{lc} \text{} & 24−|19−3(6−2)| \\ \text{Work inside parentheses first:} & \text{} \\ \text{subtract 2 from 6.} & 24−|19−3(4)| \\ \text{Multiply 3(4).} & 24−|19−12| \\ \text{Subtract inside the absolute value bars.} & 24−|7| \\ \text{Take the absolute value.} & 24−7 \\ \text{Subtract.} & 17 \end{array}\)

Simplify: \(19−|11−4(3−1)|\).

- Answer

-

16

Add and Subtract Integers

So far in our examples, we have only used the counting numbers and the whole numbers.

\[\begin{array}{ll} \text{Counting numbers} & 1,2,3… \\ \text{Whole numbers} & 0,1,2,3…. \end{array}\nonumber\]

Our work with opposites gives us a way to define the integers. The whole numbers and their opposites are called the integers. The integers are the numbers \(…−3,−2,−1,0,1,2,3…\)

The whole numbers and their opposites are called the integers.

The integers are the numbers

\[…-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3…,\nonumber\]

Most students are comfortable with the addition and subtraction facts for positive numbers. However, adding or subtracting with both positive and negative numbers may be more challenging.

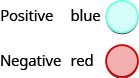

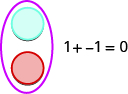

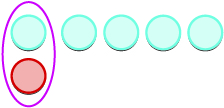

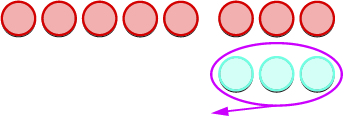

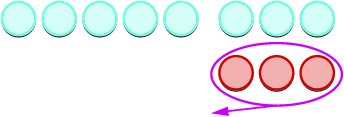

We will use two-color counters to model the addition and subtraction of negatives so that you can visualize the procedures instead of memorizing the rules.

We let one color (blue) represent positive. The other color (red) will represent the negatives.

If we have one positive counter and one negative counter, the value of the pair is zero. They form a neutral pair. The value of this neutral pair is zero.

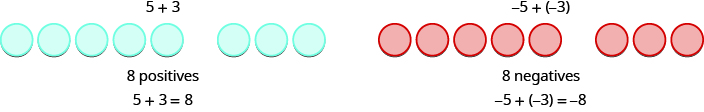

We will use the counters to show how to add:

\[5+3 \; \; \; \; \; \; −5+(−3) \; \; \; \; \; \; −5+3 \; \; \; \; \; \; \; 5+(−3)\nonumber\]

The first example, \(5+3,\) adds 5 positives and 3 positives—both positives.

The second example, \(−5+(−3),\) adds 5 negatives and 3 negatives—both negatives.

When the signs are the same, the counters are all the same color, so we add them. In each case, we get 8—either 8 positives or 8 negatives.

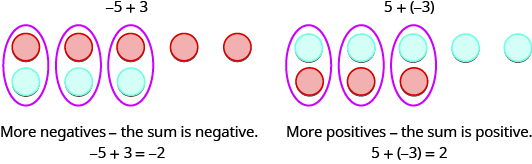

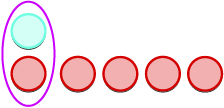

So what happens when the signs are different? Let’s add \(−5+3\) and \(5+(−3)\).

When we use counters to model addition of positive and negative integers, it is easy to see whether there are more positive or more negative counters. So we know whether the sum will be positive or negative.

Perform the following addition:

a. \(−1+(−4)\)

b. \(−1+5\)

c. \(1+(−5)\)

Solution

a.

|

|

|

|

| 1 negative plus 4 negatives is 5 negatives |  |

b.

|

|

|

|

| There are more positives, so the sum is positive. |  |

c.

|

|

|

|

| There are more negatives, so the sum is negative. |  |

Add:

a. \(−2+(−4)\)

b. \(−2+4\)

c. \(2+(−4)\)

- Answer

-

a. \(−6\)

b. \(2\)

c. \(−2\)

We will continue to use counters to model the subtraction. Perhaps when you were younger, you read \(“5−3”\) as “5 take away 3.” When you use counters, you can think of subtraction the same way!

We will use the counters to show to subtract:

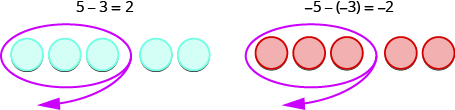

\[5−3 \; \; \; \; \; \; −5−(−3) \; \; \; \; \; \; −5−3 \; \; \; \; \; \; 5−(−3) \nonumber\]

The first example, \(5−3\), we subtract 3 positives from 5 positives and end up with 2 positives.

In the second example, \(−5−(−3),\) we subtract 3 negatives from 5 negatives and end up with 2 negatives.

Each example used counters of only one color, and the “take away” model of subtraction was easy to apply.

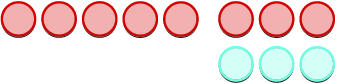

What happens when we have to subtract one positive and one negative number? We’ll need to use both blue and red counters as well as some neutral pairs. If we don’t have the number of counters needed to take away, we add neutral pairs. Adding a neutral pair does not change the value. It is like changing quarters to nickels—the value is the same, but it looks different.

Let’s look at \(−5−3\) and \(5−(−3)\).

|

|

|

| Model the first number. |  |

|

| We now add the needed neutral pairs. |  |

|

| We remove the number of counters modeled by the second number. |  |

|

| Count what is left. |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perform the following subtraction:

a. \(3−1\)

b. \(−3−(−1)\)

c. \(−3−1\)

d. \(3−(−1)\)

Solution

a.

|

|

|

| Take 1 positive from 3 positives and get 2 positives. |  |

b.

|

|

|

| Take 1 positive from 3 negatives and get 2 negatives. |  |

c.

|

|

|

| Take 1 positive from the one added neutral pair. |  |

|

d.

|

|

|

| Take 1 negative from the one added neutral pair. |  |

|

Perform the following Subtraction:

a. \(7−4\)

b. \(−7−(−4)\)

c. \(−7−4\)

d. \(7−(−4)\)

- Answer

-

a. \(3\)

b. \(−3\)

c. \(−11\)

d. \(11\)

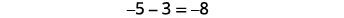

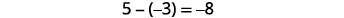

Have you noticed that subtraction of signed numbers can be done by adding the opposite? In the last example, \(−3−1\) is the same as \(−3+(−1)\) and \(3−(−1)\) is the same as \(3+1\). You will often see this idea, the Subtraction Property, written as follows:

\[a−b=a+(−b)\nonumber\]

Subtracting a number is the same as adding its opposite.

Simplify:

a. \(13−8\) and \(13+(−8)\)

b. \(−17−9\) and \(−17+(−9)\)

c. \(9−(−15)\) and \(9+15\)

d. \(−7−(−4)\) and \(−7+4\)

Solution

a. \(\begin{array}{lccc} \text{} & 13−8 & \text{and} & 13+(−8) \\ \text{Subtract.} & 5 & \text{} & 5 \end{array}\)

b. \(\begin{array}{lccc} \text{} & −17−9 & \text{and} & −17+(−9) \\ \text{Subtract.} & −26 & \text{} & −26 \end{array}\)

c. \(\begin{array}{lccc} \text{} & 9−(−15) & \text{and} & 9+15 \\ \text{Subtract.} & 24 & \text{} & 24 \end{array}\)

d. \(\begin{array}{lccc} \text{} & −7−(−4) & \text{and} & −7+4 \\ \text{Subtract.} & −3 & \text{} & −3 \end{array}\)

Simplify:

a. \(15−7\) and \(15+(−7)\)

b. \(−14−8\) and \(−14+(−8)\)

c. \(4−(−19)\) and \(4+19\)

d. \(−4−(−7)\) and \(−4+7\).

- Answer

-

a. \(8,8\)

b. \(−22,−22\)

c. \(23,23\)

d. \(3,3\)

What happens when there are more than three integers? We just use the order of operations as usual.

Simplify: \(7−(−4−3)−9.\)

Solution

\(\begin{array}{lc} \text{} & 7−(−4−3)−9 \\ \text{Simplify inside the parentheses first.} & 7−(−7)−9 \\ \text{Subtract left to right.} & 14−9 \\ \text{Subtract.} & 5 \end{array}\)

Simplify: \(8−(−3−1)−9\).

- Answer

-

\(3\)

Multiply and Divide Integers

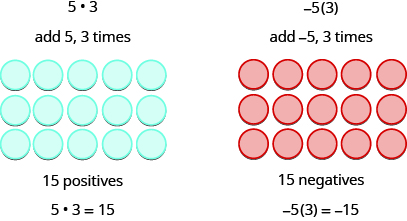

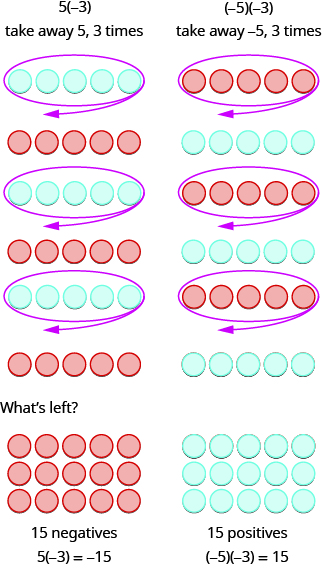

Since multiplication is mathematical shorthand for repeated addition, our model can easily be applied to show multiplication of integers. Let’s look at this concrete model to see what patterns we notice. We will use the same examples that we used for addition and subtraction. Here, we are using the model just to help us discover the pattern.

We remember that a⋅b means add a, b times.

The next two examples are more interesting. What does it mean to multiply 5 by −3? It means subtract 5 from itself three times. Looking at subtraction as “taking away”, it means to take away 5, 3 times. But there is nothing to take away, so we start by adding neutral pairs on the workspace.

In summary:

\[\begin{array}{ll} 5·3=15 & −5(3)=−15 \\ 5(−3)=−15 & (−5)(−3)=15 \end{array}\nonumber\]

Notice that for multiplication of two signed numbers, when the

\[ \text{signs are the } \textbf{same} \text{, the product is } \textbf{positive.} \\ \text{signs are } \textbf{different} \text{, the product is } \textbf{negative.} \nonumber\]

What about division? Division is the inverse operation of multiplication. So, \(15÷3=5\) because \(15·3=15\). In words, this expression says that 15 can be divided into 3 groups of 5 each because adding five three times gives 15. If you look at some examples of multiplying integers, you might figure out the rules for dividing integers.

\[\begin{array}{lclrccl} 5·3=15 & \text{so} & 15÷3=5 & \text{ } −5(3)=−15 & \text{so} & −15÷3=−5 \\ (−5)(−3)=15 & \text{so} & 15÷(−3)=−5 & \text{ } 5(−3)=−15 & \text{so} & −15÷(−3)=5 \end{array}\nonumber\]

Division follows the same rules as multiplication with regard to signs.

For multiplication and division of two signed numbers:

| Same signs | Result |

|---|---|

| • Two positives | Positive |

| • Two negatives | Positive |

If the signs are the same, the result is positive.

| Different signs | Result |

|---|---|

| • Positive and negative | Negative |

| • Negative and positive | Negative |

If the signs are different, the result is negative.

Multiply or divide:

a. \(−100÷(−4)\)

b. \(7⋅6\)

c. \(4(−8)\)

d. \(−27÷3\)

Solution

a. \(\begin{array}{lc} \text{} & −100÷(−4) \\ \text{Divide, with signs that are} \\ \text{the same the quotient is positive.} & 25 \end{array}\)

b. \(\begin{array} {lc} \text{} & 7·6 \\ \text{Multiply, with same signs.} & 42 \end{array}\)

c. \(\begin{array} {lc} \text{} & 4(−8) \\ \text{Multiply, with different signs.} & −32 \end{array}\)

d. \(\begin{array}{lc} \text{} & −27÷3 \\ \text{Divide, with different signs,} \\ \text{the quotient is negative.} & −9 \end{array}\)

Multiply or divide:

a. \(−117÷(−3)\)

b. \(3⋅13\)

c. \(7(−4)\)

d. \(−42÷6\).

- Answer

-

a. \(39\)

b. \(39\)

c. \(−28\)

d. \(−7\)

When we multiply a number by 1, the result is the same. Each time we multiply a number by −1, we get its opposite!

\[−1a=−a\nonumber\]

Multiplying a number by \(−1\) gives its opposite.

Simplify Expressions with Integers

What happens when there are more than two numbers in an expression? The order of operations still applies when negatives are included. Remember Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally?

Let’s try some examples. We’ll simplify expressions that use all four operations with integers—addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Remember to follow the order of operations.

Simplify:

a. \((−2)^4\)

b. \(−2^4\).

Solution

Notice the difference in parts a and b. In a, the exponent applies to all of \((−2)\), while in b, it only applies to the 2.

a. \(\begin{array}{lc} \text{} & (−2)^4 \\ \text{Write in expanded form.} & (−2)(−2)(−2)(−2) \\ \text{Multiply.} & 4(−2)(−2) \\ \text{Multiply.} & −8(−2) \\ \text{Multiply.} & 16 \end{array}\)

b. \(\begin{array}{lc} \text{} & −2^4 \\ \text{Write in expanded form.} & −(2·2·2·2) \\ \text{Multiply.} & −(4·2·2) \\ \text{Multiply.} & −(8·2) \\ \text{Multiply.} & −16 \end{array}\)

Simplify:

a. \((−3)^4\)

b. \(−3^4\).

- Answer

-

a. \(81\)

b. \(−81\)

The last example showed us the difference between \((−2)^4\) and \(−2^4\). This distinction is important to prevent future errors. The following example reminds us to multiply and divide in order left to right.

Simplify:

a. \(8(−9)÷(−2)^3\)

b. \(−30÷2+(−3)(−7)\)

Solution

a. \(\begin{array}{lc} \text{} & 8(−9)÷(−2)^3 \\ \text{Exponents first.} & 8(−9)÷(−8) \\ \text{Multiply.} & −72÷(−8) \\ \text{Divide.} & 9 \end{array}\)

b. \(\begin{array}{lc} \text{} & −30÷2+(−3)(−7) \\ \text{Divide first.} & −15+(−3)(−7) \\ \text{Multiply.} & −15+21 \\ \text{Add.} & 6 \end{array}\)

Simplify:

a. \(18(−4)÷(−2)^3\)

b. \(−32÷4+(−2)(−7)\).

- Answer

-

a. \(9\)

b. \(6\)

Evaluate Variable Expressions with Integers

Remember that to evaluate an expression means to substitute a number for the variable in the expression. Now we can use negative numbers as well as positive numbers.

Evaluate \(4x^2−2xy+3y^2\) when \(x=2, y=−1\).

Solution

\(\begin{array}{lc} \text{} & 4x^2 − 2xy + 3y^2 \\ \text{Substitute.} & 4(2)^2 − 2(2)(−1) + 3(−1)^2 \\ \text{Simplify exponents.} & 4(4) − 2(2)(−1) + 3(1) \\ \text{Multiply.} & 16 + 4 + 3 \\ \text{Add.} & 23 \end{array}\)

Evaluate: \(3x^2−2xy+6y^2\) when \(x=1, y=−2\).

- Answer

-

\(31\)

Translate Phrases to Expressions with Integers

Our earlier work translating English to algebra also applies to phrases that include both positive and negative numbers.

Translate and simplify: the sum of 8 and −12, increased by 3.

Solution

\(\begin{array}{lc} \text{Translate.} & [8 + (−12)] + 3 \\ \text{Simplify inside the brackets.} & −4 + 3 \\ \text{Add.} & −1 \end{array}\)

Translate and simplify the sum of 9 and −16, increased by 4.

- Answer

-

\((9+(−16))+4 = −3\)

Use Integers in Applications

We’ll outline a plan to solve applications. It’s hard to find something if we don’t know what we’re looking for or what to call it! So when we solve an application, we first need to determine what the problem is asking us to find. Then we’ll write a phrase that gives the information to find it. We’ll translate the phrase into an expression and then simplify the expression to get the answer. Finally, we summarize the answer in a sentence to make sure it makes sense.

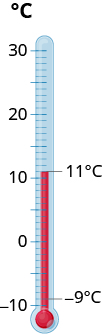

The temperature in Kendallville, Indiana one morning was 11 degrees. By mid-afternoon, the temperature had dropped to −9 degrees. What was the difference in the morning and afternoon temperatures?

Solution

\(\begin{array}{lc} \text{Identify the problem.} & \text{We are asked to find the difference between 11 and −9.} \\ \text{Translate.} & 11 - (−9) \\ \text{Subtracting a negative becomes addition.} & 11 + 9 \\ \text{Add.} & 20 \end{array}\)

The difference in temperatures was 20 degrees.

The temperature in Anchorage, Alaska one morning was 15 degrees. By mid-afternoon the temperature had dropped to 30 degrees below zero. What was the difference in the morning and afternoon temperatures?

- Answer

-

The difference in temperatures was 45 degrees Fahrenheit.