Section 1.5: Fractions

- Page ID

- 182863

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)We will rely heavily on these skills throughout this section.

- List the first 10 prime numbers.

- Find the least common multiple of 6 and 15.

- Determine the prime factorization of 48.

Motivating Problem

You need ¾ cup of flour and ⅔ cup of sugar for a recipe. If you want to make a half batch, how much of each ingredient should you use?

Fun Fact

The word “fraction” comes from the Latin fractio, meaning “to break.” Ancient Egyptians wrote all their fractions with a numerator of 1 and used special symbols for them, employing clever techniques to represent quantities like 2/3 or 3/4 without our modern notation.

The Goal

In this section, we delve into fractions in depth, exploring what they represent, how to simplify them, and how to perform operations such as multiplication, division, addition, and subtraction. We'll learn how fractions represent parts of a whole and how to use models, patterns, and logic to work fluently with them in real-life and algebraic contexts.

Simplify Fractions

A fraction is a way to represent parts of a whole. The fraction \(\frac{2}{3}\) represents two of three equal parts. In the fraction \(\frac{2}{3}\), the 2 is called the numerator and the 3 is called the denominator. The line is called the fraction bar.

In the circle, \(\frac{2}{3}\) of the circle is shaded—2 of the 3 equal parts.

A fraction is written \(\dfrac{a}{b}\), where \(b\neq 0\) and

\(a\) is the numerator and \(b\) is the denominator.

A fraction represents parts of a whole. The denominator \(b\) is the number of equal parts the whole has been divided into, and the numerator \(a\) indicates how many parts are included.

Fractions that have the same value are equivalent fractions. The Equivalent Fractions

Property allows us to find equivalent fractions and also simplify fractions.

If \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\) are numbers where \(b\neq 0,c\neq 0\),

then \(\dfrac{a}{b}=\dfrac{a·c}{b·c}\) and \(\dfrac{a·c}{b·c}=\dfrac{a}{b}.\)

A fraction is considered simplified if there are no common factors, other than 1, in its numerator and denominator.

For example,

\(\dfrac{2}{3}\) is simplified because there are no common factors of \(2\) and \(3\).

\(\dfrac{10}{15}\) is not simplified because \(5\) is a common factor of \(10\) and \(15\).

We simplify, or reduce, a fraction by dividing out the common factors of the numerator and denominator. A fraction is not simplified until all common factors have been divided out. If an expression has fractions, it is not completely simplified until the fractions are simplified.

Sometimes it may not be easy to find common factors of the numerator and denominator. When this happens, a good idea is to factor the numerator and the denominator into prime numbers. Then divide out the common factors using the Equivalent Fractions Property.

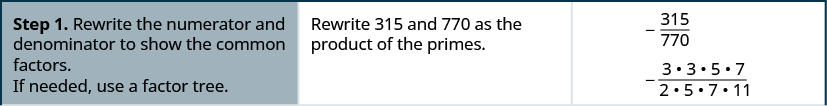

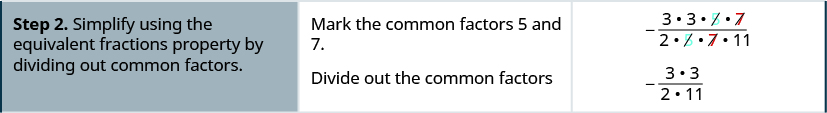

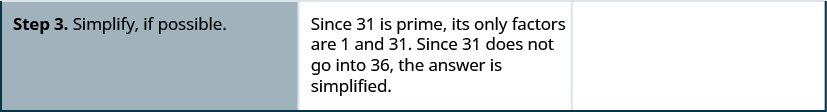

Simplify \(\dfrac{−315}{770}\).

Solution

Simplify \(−\dfrac{120}{192}\).

- Answer

-

\(−\dfrac{5}{8}\)

We now summarize the steps you should follow to simplify fractions.

- Rewrite the numerator and denominator to show the common factors.

If needed, factor the numerator and denominator into prime numbers first. - Simplify using the Equivalent Fractions Property by dividing out common factors.

- Multiply any remaining factors.

Multiply and Divide Fractions

Many people find multiplying and dividing fractions easier than adding and subtracting fractions.

To multiply fractions, we multiply the numerators and multiply the denominators.

If \(a\), \(b\), \(c\), and \(d\) are numbers where \(b≠0\), and \(d≠0\), then

\[\frac{a}{b}·\frac{c}{d}=\frac{ac}{bd}\nonumber\]

To multiply fractions, multiply the numerators and multiply the denominators.

When multiplying fractions, the properties of positive and negative numbers still apply, of course. It is a good idea to determine the sign of the product as the first step. In the following example, we will multiply a negative number and a positive number, so the product will be negative.

When multiplying a fraction by an integer, it may be helpful to write the integer as a fraction. Any integer, a, can be written as \(\dfrac{a}{1}\). So, for example, \(3=\dfrac{3}{1}\).

Multiply: \(−\dfrac{12}{5}(−20x).\)

Solution

The first step is to find the sign of the product. Since the signs are the same, the product is positive.

|

|

|

Determine the sign of the product. The signs are the same, so the product is positive. |

|

| Write 20x as a fraction. |  |

| Multiply. |  |

|

Rewrite 20 to show the common factor 5 and divide it out. |

|

| Simplify. | \(48x\) |

Multiply: \(\dfrac{11}{3}(−9a)\).

- Answer

-

\(−33a\)

Now that we know how to multiply fractions, we are almost ready to divide. Before we can do that, we need some vocabulary. The reciprocal of a fraction is found by inverting the fraction, placing the numerator in the denominator, and the denominator in the numerator. The reciprocal of \(\frac{2}{3}\) is \(\frac{3}{2}\). Since 4 is written in fraction form as \(\frac{4}{1}\), the reciprocal of 4 is \(\frac{1}{4}\).

To divide fractions, we multiply the first fraction by the reciprocal of the second.

If \(a\), \(b\), \(c\), and \(d\) are numbers where \(b≠0\),\(c≠0\), and \(d≠0\), then

\[\frac{a}{b}÷\frac{c}{d}=\frac{a}{b}⋅\frac{d}{c}\nonumber\]

To divide fractions, we multiply the first fraction by the reciprocal of the second.

We need to say \(b≠0\), \(c≠0\), and \(d≠0\), to be sure we don’t divide by zero!

Find the quotient: \(−\dfrac{7}{18}÷(−\dfrac{14}{27}).\)

Solution

| \(−\dfrac{7}{18}÷(−\dfrac{14}{27})\) | |

|

To divide, multiply the first fraction by the reciprocal of the second. |

|

|

Determine the sign of the product, and then multiply. |

|

| Rewrite showing common factors. |  |

| Remove common factors. |  |

| Simplify. | \(\dfrac{3}{4}\) |

Divide: \(−\dfrac{7}{27}÷(−\dfrac{35}{36})\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{4}{15}\)

The numerators or denominators of some fractions contain fractions themselves. A fraction in which the numerator or the denominator is a fraction is called a complex fraction.

A complex fraction is a fraction in which the numerator or the denominator contains a fraction.

Some examples of complex fractions are:

\[\dfrac{\frac{6}{7}}{3} \quad \dfrac{\frac{3}{4}}{\frac{5}{8}} \quad \dfrac{\frac{x}{2}}{ \frac{5}{6}}\nonumber\]

To simplify a complex fraction, remember that the fraction bar means division. For example, the complex fraction \(\dfrac{\frac{3}{4}}{\frac{5}{8}}\) means \(\dfrac{3}{4}÷\dfrac{5}{8}.\)

Simplify: \(\dfrac{\dfrac{x}{2}}{ \dfrac{xy}{6}}\).

Solution

\(\begin{array}{lc} \text{} & \dfrac{\dfrac{x}{2}}{ \dfrac{xy}{6}} \\[6pt] \text{Rewrite as division.} & \dfrac{x}{2}÷\dfrac{xy}{6} \\[6pt] \text{Multiply the first fraction by the reciprocal of the second.} & \dfrac{x}{2}·\dfrac{6}{xy} \\[6pt] \text{Multiply.} & \dfrac{x·6}{2·xy} \\[6pt] \text{Look for common factors.} & \dfrac{ \cancel{x}·3·\cancel{2}}{\cancel{2}·\cancel{x}·y} \\[6pt] \text{Divide common factors and simplify.} & \dfrac{3}{y} \end{array}\)

Simplify: \(\dfrac{\dfrac{a}{8}}{ \dfrac{ab}{6}}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{3}{4b}\)

Add and Subtract Fractions

When we multiply fractions, we multiply the numerators and denominators directly. However, to add or subtract fractions, they must have a common denominator.

If \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\) are numbers where \(c≠0\), then

\[\dfrac{a}{c}+\dfrac{b}{c}=\dfrac{a+b}{c} \text{ and } \dfrac{a}{c}−\dfrac{b}{c}=\dfrac{a−b}{c}\nonumber\]

To add or subtract fractions, add or subtract the numerators and place the result over the common denominator.

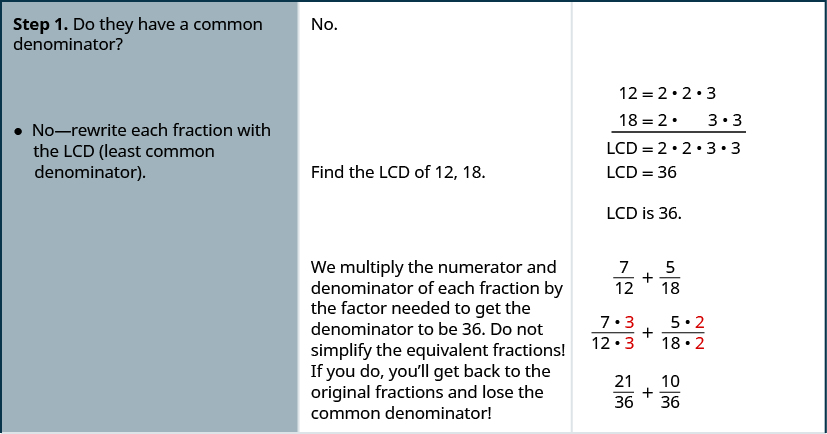

The least common denominator (LCD) of two fractions is the smallest number that can be used as a common denominator of the fractions. The LCD of the two fractions is the least common multiple (LCM) of their denominators.

The least common denominator (LCD) of two fractions is the least common multiple (LCM) of their denominators.

After we find the least common denominator of two fractions, we convert the fractions to equivalent fractions with the LCD. Putting these steps together allows us to add and subtract fractions because their denominators will be the same!

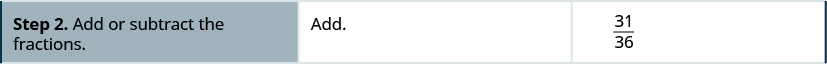

Add: \(\dfrac{7}{12}+\dfrac{5}{18}\).

Solution

Add: \(\dfrac{13}{15}+\dfrac{17}{20}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{103}{60}\)

- Do they have a common denominator?

- Yes—go to step 2.

- No—rewrite each fraction with the LCD (least common denominator).

- Find the LCD.

- Change each fraction into an equivalent fraction with the LCD as its denominator.

- Add or subtract the fractions.

- Simplify, if possible.

We now have all four operations for fractions. The table below summarizes fraction operations.

| Fraction Multiplication | Fraction Division |

|---|---|

| \(\dfrac{a}{b}⋅\dfrac{c}{d}=\dfrac{ac}{bd}\) | \(\dfrac{a}{b}÷\dfrac{c}{d}=\dfrac{a}{b}⋅\dfrac{d}{c}\) |

| Multiply the numerators and multiply the denominators | Multiply the first fraction by the reciprocal of the second. |

| Fraction Addition | Fraction Subtraction |

| \(\dfrac{a}{c}+\dfrac{b}{c}=\dfrac{a+b}{c}\) | \(\dfrac{a}{c}−\dfrac{b}{c}=\dfrac{a−b}{c}\) |

| Add the numerators and place the sum over the common denominator. | Subtract the numerators and place the difference over the common denominator. |

|

To multiply or divide fractions, an LCD is NOT needed. To add or subtract fractions, an LCD is needed. |

|

When starting an exercise, always identify the operation and then recall the methods needed for that operation.

Simplify:

a. \(\dfrac{5x}{6}−\dfrac{3}{10}\)

b. \(\dfrac{5x}{6}·\dfrac{3}{10}\).

Solution

First ask, “What is the operation?” Identifying the operation will determine whether or not we need a common denominator. Remember, we need a common denominator to add or subtract, but not to multiply or divide.

a.

\(\begin{array}{lc} \text{What is the operation? The operation is subtraction.} \\[6pt] \text{Do the fractions have a common denominator? No.} & \dfrac{5x}{6} − \dfrac{3}{10} \\[6pt] \text{Find the LCD of }6 \text{ and }10 & \text{The LCD is 30.}\\[6pt] {\begin{align*} 6 & =2·3 \\[6pt]

\; \; \underline{\; \; \; \; 10 \; \; \; \; } & \underline{=2·5 \; \; \; \;} \; \\[6pt]

\text{LCD} & =2·3·5 \\[6pt]

\text{LCD} & =30 \end{align*}} \\[6pt] \\ \\

\text{Rewrite each fraction as an equivalent fraction with the LCD.} & \dfrac{5x·5}{6·5}−\dfrac{3·3}{10·3}\\[6pt]

\text{} & \dfrac{25x}{30}−\dfrac{9}{30} \\[6pt]

\text{Subtract the numerators and place the} \\[6pt]

\text{difference over the common denominator.} & \dfrac{25x−9}{30} \\[6pt] \\ \\

\text{Simplify,if possible.There are no common factors.} \\[6pt]

\text{The fraction is simplified.} \end{array}\)

b.

\(\begin{array}{lc} \text{What is the operation? Multiplication.} & \dfrac{5x}{6}·\dfrac{3}{10} \\ \text{To multiply fractions,multiply the numerators} \\ \text{and multiply the denominators.} & \dfrac{5x·3}{6·10} \\ \text{Rewrite, showing common factors.} \\ \text{Remove common factors.} & \dfrac{\cancel{5} x · \cancel{3}}{2·\cancel{3}·2·\cancel{5}} \\ \text{Simplify.} & \dfrac{x}{4} \end{array}\)

Notice, we needed an LCD to add \(\dfrac{5x}{6}−\dfrac{3}{10}\), but not to multiply \(\dfrac{5x}{6}⋅\dfrac{3}{10}\).

Simplify:

a. \(\dfrac{3a}{4}−\dfrac{8}{9}\)

b. \(\dfrac{3a}{4}·\dfrac{8}{9}\)

- Answer

-

a. \(\dfrac{27a−32}{36}\)

b. \(\dfrac{2a}{3}\)

Use the Order of Operations to Simplify Fractions

The fraction bar in a fraction acts as a grouping symbol. The order of operations then tells us to simplify the numerator and then the denominator. Then we divide.

- Simplify the expression in the numerator. Simplify the expression in the denominator.

- Simplify the fraction.

Where does the negative sign go in a fraction? Usually, the negative sign is in front of the fraction, but you will sometimes see a fraction with a negative numerator, or sometimes with a negative denominator. Remember that fractions represent division. When the numerator and denominator have different signs, the quotient is negative.

\[\dfrac{−1}{3}=−\dfrac{1}{3} \; \; \; \; \; \; \dfrac{\text{negative}}{\text{positive}}=\text{negative}\nonumber\]

\[\dfrac{1}{−3}=−\dfrac{1}{3} \; \; \; \; \; \; \dfrac{\text{positive}}{\text{negative}}=\text{negative}\nonumber\]

For any positive numbers \(a\) and \(b\),

\[\dfrac{−a}{b}=\dfrac{a}{−b}=−\dfrac{a}{b}\nonumber\]

Simplify: \(\dfrac{4(−3)+6(−2)}{−3(2)−2}\).

Solution

The fraction bar acts like a grouping symbol. So, completely simplify the numerator and the denominator separately.

\(\begin{array}{lc} \text{} & \dfrac{4(−3)+6(−2)}{−3(2)−2} \\[5pt] \text{Multiply.} & \dfrac{−12+(−12)}{−6−2} \\[5pt] \text{Simplify.} & \dfrac{−24}{−8} \\[5pt] \text{Divide.} & 3 \end{array}\)

Simplify:\(\dfrac{8(−2)+4(−3)}{−5(2)+3}\).

- Answer

-

4

Now we’ll look at complex fractions where the numerator or denominator contains an expression that can be simplified. Therefore, we must first simplify the numerator and denominator separately, following the order of operations. Then we divide the numerator by the denominator, as the fraction bar means division.

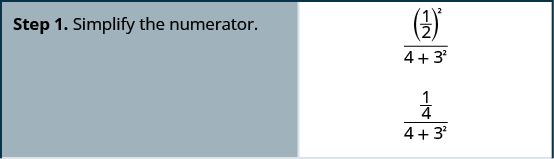

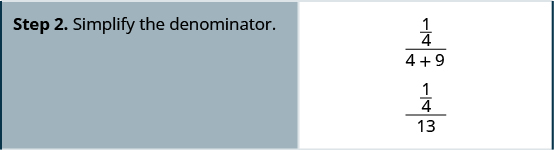

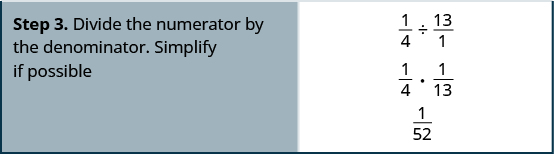

Simplify: \(\dfrac{\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^2}{4+3^2}\).

Solution

Simplify: \(\dfrac{1+4^2}{\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^2}\).

- Answer

-

272

- Simplify the numerator.

- Simplify the denominator.

- Divide the numerator by the denominator. Simplify if possible.

Simplify: \(\dfrac{\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{2}{3}}{\dfrac{3}{4}−\dfrac{1}{6}}\).

Solution

It may help to put parentheses around the numerator and the denominator.

\(\begin{array}{lc}\text{} & \dfrac{\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{2}{3}}{\dfrac{3}{4}−\dfrac{1}{6}} \\[6pt] \text{Simplify the numerator }(LCD=6)\text{ and } \\[6pt] \text{simplify the denominator }(LCD=12). & \dfrac{\left(\dfrac{3}{6}+\dfrac{4}{6}\right)}{\left(\dfrac{9}{12}−\dfrac{2}{12}\right)} \\[6pt] \text{Simplify.} & \dfrac{\left(\dfrac{7}{6}\right)}{\left(\dfrac{7}{12}\right)} \\[6pt] \text{Divide the numerator by the denominator.} & \dfrac{7}{6}÷\dfrac{7}{12} \\[6pt] \text{Simplify.} & \dfrac{7}{6}⋅\dfrac{12}{7} \\[6pt] \text{Divide out common factors.} & \dfrac{\cancel{7}⋅\cancel{6}⋅2}{ \cancel{6}⋅\cancel{7}⋅1} \\[6pt] \text{Simplify.} & 2 \end{array}\)

Simplify: \(\dfrac{\dfrac{2}{3}−\dfrac{1}{2}}{ \dfrac{1}{4}+\dfrac{1}{3}}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{2}{7}\)

Evaluate Variable Expressions with Fractions

We have evaluated expressions before, but can now evaluate expressions with fractions. Remember, to evaluate an expression, we substitute the variable's value into the expression and then simplify.

Evaluate \(2x^2y\) when \(x=\frac{1}{4}\) and \(y=−\frac{2}{3}\).

Solution

| \(2x^2y\) | |

| Substitute \(\dfrac{1}{4}\) for \(x\) and \(−\dfrac{2}{3}\) for \(y\). | \(2\left(\dfrac{1}{4}\right)^2\left(-\dfrac{2}{3}\right)\) |

| Simplify exponents first. | \(2\left(\dfrac{1}{16}\right)\left(-\dfrac{2}{3}\right)\) |

| Multiply; divide out the common factors. Notice we write \(16\) as \(2\cdot 2\cdot 4\) to make it easy to remove common factors. | \(-\dfrac{2\cdot 1\cdot 2}{2\cdot 2\cdot 4\cdot 3}\) |

| Simplify. | \(-\dfrac{1}{12}\) |

Evaluate \(3ab^2\) when \(a=−\frac{2}{3}\) and \(b=−\frac{1}{2}\).

- Answer

-

\(−\dfrac{1}{2}\)