10.3: The Six Circular Functions and Fundamental Identities

- Page ID

- 119196

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

The Six Circular Functions - Unit Circle Definition

In Section 10.2, we defined \(\cos(\theta)\) and \(\sin(\theta)\) for angles \(\theta\) using the coordinate values of points on the Unit Circle. As such, these functions earn the moniker circular functions.1 It turns out that cosine and sine are just two of the six commonly used circular functions which we define below.

Suppose \(\theta\) is an angle plotted in standard position and \(P(x,y)\) is the point on the terminal side of \(\theta\) which lies on the Unit Circle.

- The cosine of \(\theta\), denoted \(\cos(\theta)\), is defined by \(\cos(\theta) = x\).

- The sine of \(\theta\), denoted \(\sin(\theta)\), is defined by \(\sin(\theta) = y\).

- The secant of \(\theta\), denoted \(\sec(\theta)\), is defined by \(\sec(\theta) = \frac{1}{x}\), provided \(x \neq 0\).

- The cosecant of \(\theta\), denoted \(\csc(\theta)\), is defined by \(\csc(\theta) = \frac{1}{y}\), provided \(y \neq 0\).

- The tangent of \(\theta\), denoted \(\tan(\theta)\), is defined by \(\tan(\theta) = \frac{y}{x}\), provided \(x \neq 0\).

- The cotangent of \(\theta\), denoted \(\cot(\theta)\), is defined by \(\cot(\theta) = \frac{x}{y}\), provided \(y \neq 0\).

While we left the history of the name "sine" as an interesting research project in Section 10.2, the names "tangent" and "secant" can be explained using the diagram below. Consider the acute angle \(\theta\) below in standard position. Let \(P(x,y)\) denote, as usual, the point on the terminal side of \(\theta\) which lies on the Unit Circle and let \(Q(1,y')\) denote the point on the terminal side of \(\theta\) which lies on the vertical line \(x=1\).

The word "tangent" comes from the Latin meaning "to touch," and for this reason, the line \(x=1\) is called a tangent line to the Unit Circle since it intersects, or "touches," the circle at only one point, namely \((1,0)\). Dropping perpendiculars from \(P\) and \(Q\) creates a pair of similar triangles \(\Delta OPA\) and \(\Delta OQB\). Thus \(\frac{y'}{y} = \frac{1}{x}\) which gives \(y' = \frac{y}{x} = \tan(\theta)\), where this last equality comes from applying the definition of circular functions. We have just shown that for acute angles \(\theta\), \(\tan(\theta)\) is the \(y\)-coordinate of the point on the terminal side of \(\theta\) which lies on the line \(x = 1\) which is tangent to the Unit Circle.

Now the word "secant" means "to cut," so a secant line is any line that "cuts through" a circle at two points.2 The line containing the terminal side of \(\theta\) is a secant line since it intersects the Unit Circle in Quadrants I and III. With the point \(P\) lying on the Unit Circle, the length of the hypotenuse of \(\Delta OPA\) is \(1\). If we let \(h\) denote the length of the hypotenuse of \(\Delta OQB\), we have from similar triangles that \(\frac{h}{1} = \frac{1}{x}\), or \(h = \frac{1}{x} = \sec(\theta)\). Hence for an acute angle \(\theta\), \(\sec(\theta)\) is the length of the line segment which lies on the secant line determined by the terminal side of \(\theta\) and "cuts off" the tangent line \(x=1\).

The following interactive object might help you visualize everything we have developed so far.

Interact: Move the point along the unit circle (from \( \theta = 0 \) to \( \theta = \frac{\pi}{2} \).

Observe: The values of both the tangent and secant climb to \( \infty \) as \( \theta \to \frac{\pi}{2} \).

Not only do these observations help explain the names of these functions, they serve as the basis for a fundamental inequality needed for Calculus which we’ll explore in the Exercises.

1 In Theorem 10.2.6 we also showed cosine and sine to be functions of an angle residing in a right triangle so we could just as easily call them trigonometric functions. In later sections, you will find that we do indeed use the phrase "trigonometric function" interchangeably with the term "circular function."

2 Compare this with the definition given in Section 2.1.

The Reciprocal and Quotient Identities

Of the six circular functions, only cosine and sine are defined for all angles. Since \(\cos(\theta) = x\) and \(\sin(\theta) = y\) in the definition of circular functions, it is customary to rephrase the remaining four circular functions in terms of cosine and sine. The following theorem is a result of simply replacing \(x\) with \(\cos(\theta)\) and \(y\) with \(\sin(\theta)\) in the definition of circular functions.

- \(\sec(\theta) = \frac{1}{\cos(\theta)}\), provided \(\cos(\theta) \neq 0\); if \(\cos(\theta) = 0\), \(\sec(\theta)\) is undefined.

- \(\csc(\theta) = \frac{1}{\sin(\theta)}\), provided \(\sin(\theta) \neq 0\); if \(\sin(\theta) = 0\), \(\csc(\theta)\) is undefined.

- \(\tan(\theta) = \frac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)}\), provided \(\cos(\theta) \neq 0\); if \(\cos(\theta) = 0\), \(\tan(\theta)\) is undefined.

- \(\cot(\theta) = \frac{\cos(\theta)}{\sin(\theta)}\), provided \(\sin(\theta) \neq 0\); if \(\sin(\theta) = 0\), \(\cot(\theta)\) is undefined.

It is high time for an example.

Find the indicated value, if it exists.

- \(\sec\left(60^{\circ}\right)\)

- \(\csc\left(\frac{7 \pi}{4} \right)\)

- \(\cot(3)\)

- \(\tan\left(\theta\right)\), where \(\theta\) is any angle coterminal with \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\).

- \(\cos\left(\theta\right)\), where \(\csc(\theta) = -\sqrt{5}\) and \(\theta\) is a Quadrant IV angle.

- \(\sin\left(\theta\right)\), where \(\tan(\theta) = 3\) and \(\pi < \theta < \frac{3\pi}{2}\).

Solution

- According to the Reciprocal Identities, \(\sec\left(60^{\circ}\right) = \frac{1}{\cos\left(60^{\circ}\right)}\). Hence, \(\sec\left(60^{\circ}\right) = \frac{1}{(1/2)} = 2\).

- Since \(\sin\left( \frac{7\pi}{4}\right) = - \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\), \(\csc\left( \frac{7\pi}{4}\right) = \frac{1}{\sin\left( \frac{7\pi}{4}\right)} = \frac{1}{- \sqrt{2}/2} = - \frac{2}{\sqrt{2}} = - \sqrt{2}\).

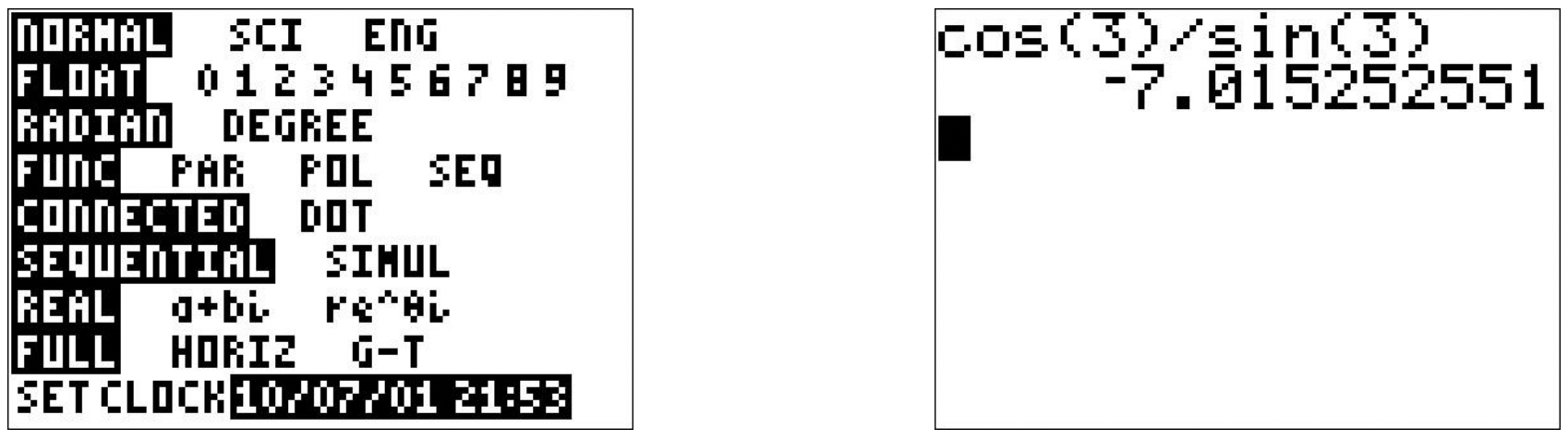

- Since \(\theta = 3\) radians is not one of the "common angles" from Section 10.2, we resort to the calculator for a decimal approximation. Ensuring that the calculator is in radian mode, we find \(\cot(3) = \frac{\cos(3)}{\sin(3)} \approx -7.015\).

- If \(\theta\) is coterminal with \(\frac{3 \pi}{2}\), then \(\cos(\theta) = \cos\left(\frac{3 \pi}{2}\right) = 0\) and \(\sin(\theta) = \sin\left(\frac{3 \pi}{2}\right) = -1\). Attempting to compute \(\tan(\theta) = \frac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)}\) results in \(\frac{-1}{0}\), so \(\tan(\theta)\) is undefined.

- We are given that \(\csc(\theta) = \frac{1}{\sin(\theta)} = -\sqrt{5}\) so \(\sin(\theta) = -\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}} = -\frac{\sqrt{5}}{5}\). As we saw in Section 10.2, we can use the Pythagorean Identity, \(\cos^{2}(\theta) + \sin^2(\theta) = 1\), to find \(\cos(\theta)\) by knowing \(\sin(\theta)\). Substituting, we get \(\cos^{2}(\theta) + \left(-\frac{\sqrt{5}}{5}\right)^2 = 1\), which gives \(\cos^{2}(\theta) = \frac{4}{5}\), or \(\cos(\theta) = \pm \frac{2 \sqrt{5}}{5}\). Since \(\theta\) is a Quadrant IV angle, \(\cos(\theta) > 0\), so \(\cos(\theta) = \frac{2 \sqrt{5}}{5}\).

- If \(\tan(\theta) = 3\), then \(\frac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)} = 3\). Be careful - this does NOT mean we can take \(\sin(\theta) = 3\) and \(\cos(\theta) = 1\). Instead, from \(\frac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)} = 3\) we get: \(\sin(\theta) = 3 \cos(\theta)\). To relate \(\cos(\theta)\) and \(\sin(\theta)\), we once again employ the Pythagorean Identity, \(\cos^{2}(\theta) + \sin^{2}(\theta) = 1\). Solving \(\sin(\theta) = 3 \cos(\theta)\) for \(\cos(\theta)\), we find \(\cos(\theta) = \frac{1}{3} \sin(\theta)\). Substituting this into the Pythagorean Identity, we find \(\sin^{2}(\theta) + \left(\frac{1}{3} \sin(\theta)\right)^2 = 1\). Solving, we get \(\sin^{2}(\theta) = \frac{9}{10}\) so \(\sin(\theta) = \pm \frac{3 \sqrt{10}}{10}\). Since \(\pi < \theta < \frac{3\pi}{2}\), \(\theta\) is a Quadrant III angle. This means \(\sin(\theta) < 0\), so our final answer is \(\sin(\theta) = - \frac{3 \sqrt{10}}{10}\).

While the Reciprocal and Quotient Identities allow us to always reduce problems involving secant, cosecant, tangent and cotangent to problems involving cosine and sine, it is not always convenient to do so.3 It is worth taking the time to memorize the tangent and cotangent values of the common angles summarized below.

Tangent and Cotangent Values of Common Angles

\[\begin{array}{|c|c||c|c|}

\hline \theta \text { (degrees) } & \theta \text { (radians) } & \tan (\theta) & \cot (\theta) \\

\hline 0^{\circ} & 0 & 0 & \text { undefined } \\

\hline 30^{\circ} & \frac{\pi}{6} & \frac{\sqrt{3}}{3} & \sqrt{3} \\

\hline 45^{\circ} & \frac{\pi}{4} & 1 & 1 \\

\hline 60^{\circ} & \frac{\pi}{3} & \sqrt{3} & \frac{\sqrt{3}}{3} \\

\hline 90^{\circ} & \frac{\pi}{2} & \text { undefined } & 0 \\

\hline

\end{array}\nonumber\]

Coupling the Reciprocal and Quotient Identities with the Reference Angle Theorem, we get the following.

The values of the circular functions of an angle, if they exist, are the same, up to a sign, of the corresponding circular functions of its reference angle. More specifically, if \(\hat{\theta}\) is the reference angle for \(\theta\), then: \(\cos(\theta) = \pm \cos(\hat{\theta})\), \(\sin(\theta) = \pm \sin(\hat{\theta})\), \(\sec(\theta) = \pm \sec(\hat{\theta})\), \(\csc(\theta) = \pm \csc(\hat{\theta})\), \(\tan(\theta) = \pm \tan(\hat{\theta})\) and \(\cot(\theta) = \pm \cot(\hat{\theta})\). The choice of the (\(\pm\)) depends on the quadrant in which the terminal side of \(\theta\) lies.

We put Theorem \( \PageIndex{2} \) to good use in the following example.

- \(\sec(\theta) =2\)

- \(\tan(\theta) = \sqrt{3}\)

- \(\cot(\theta) = -1\).

Solution

- To solve \(\sec(\theta) = 2\), we convert to cosines and get \(\frac{1}{\cos(\theta)} = 2\) or \(\cos(\theta) = \frac{1}{2}\). This is the exact same equation we solved in Example 10.2.5, so we know the answer is: \(\theta = \frac{\pi}{3} + 2\pi k\) or \(\theta = \frac{5\pi}{3} + 2\pi k\) for integers \(k\).

- From the table of common values, we see that the tangent of \( \frac{\pi}{3} \) is \( \sqrt{3} \). Thus, our reference angle is \( \frac{\pi}{3} \). Since the tangent is \( \frac{y}{x} \) and \( \sqrt{3} \) is positive, we are looking for quadrants where the \( x \)- and \( y \)-values have the same sign. This occurs in Quadrants I (where both \( x \gt 0 \) and \( y \gt 0 \)) and III (where \( x \lt 0 \) and \( y \lt 0 \)). The Quadrant I solution is \( \theta = \frac{\pi}{3} + 2 \pi k \) and the Quadrant III solution is \( \theta = \frac{4 \pi}{3} + 2 \pi k \). However, we can combine these solutions into a more succinct statement: \( \theta = \frac{\pi}{3} + \pi k \). Do you see why?

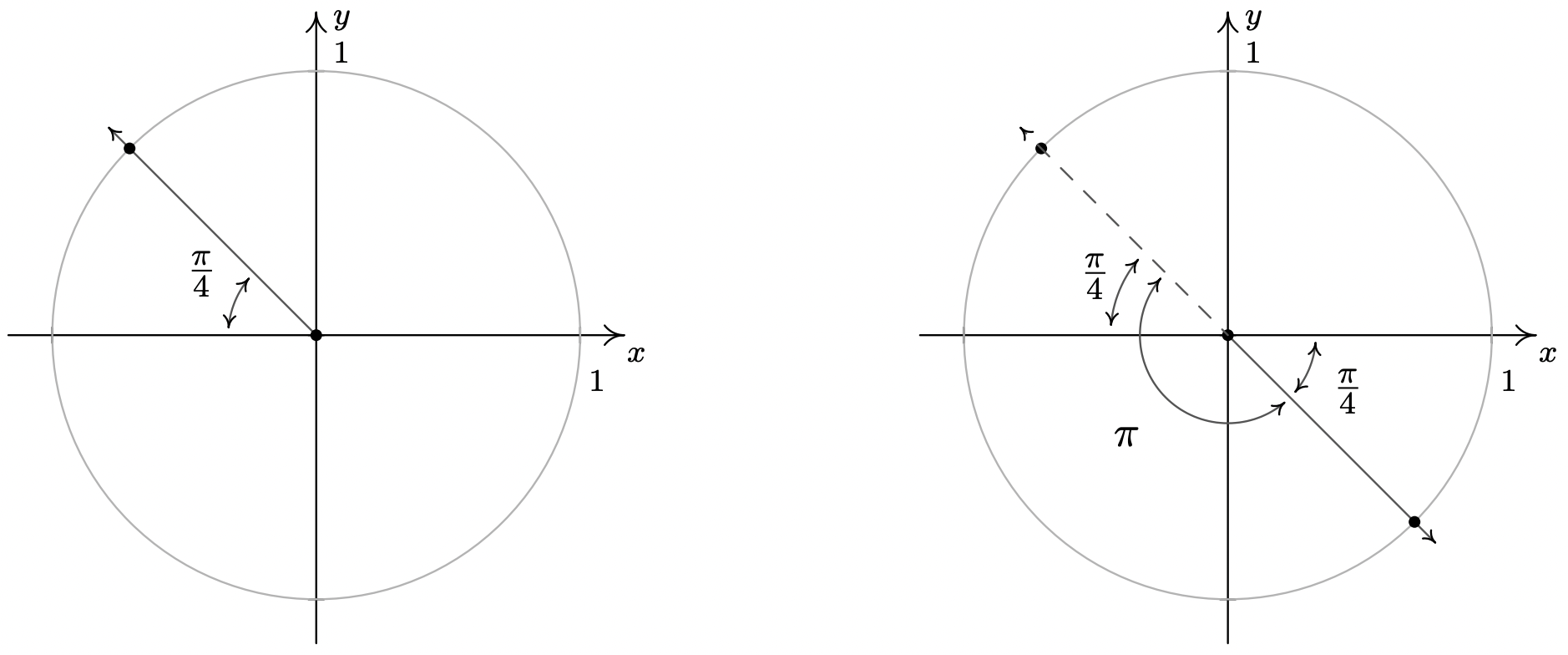

- From the table of common values, we see that \(\frac{\pi}{4}\) has a cotangent of \(1\), which means the solutions to \(\cot(\theta) = -1\) have a reference angle of \(\frac{\pi}{4}\). To find the quadrants in which our solutions lie, we note that \(\cot(\theta) = \frac{x}{y}\) for a point \((x,y)\) on the Unit Circle where \(y \neq 0\). If \(\cot(\theta)\) is negative, then \(x\) and \(y\) must have different signs (i.e., one positive and one negative.) Hence, our solutions lie in Quadrants II and IV. Our Quadrant II solution is \(\theta = \frac{3\pi}{4} + 2\pi k\), and for Quadrant IV, we get \(\theta = \frac{7\pi}{4} + 2\pi k\) for integers \(k\). Can these lists be combined? Indeed they can - one such way to capture all the solutions is: \(\theta = \frac{3\pi}{4} + \pi k\) for integers \(k\).

3 As we shall see shortly, when solving equations involving secant and cosecant, we usually convert back to cosines and sines. However, when solving for tangent or cotangent, we usually stick with what we’re dealt.

The Pythagorean Identities

We have already seen the importance of identities in trigonometry. Our next task is to use use the Reciprocal and Quotient Identities coupled with the Pythagorean Identity found in Theorem 10.2.1 to derive new Pythagorean-like identities for the remaining four circular functions. Assuming \(\cos(\theta) \neq 0\), we may start with \(\cos^{2}(\theta) + \sin^{2}(\theta) = 1\) and divide both sides by \(\cos^{2}(\theta)\) to obtain \(1 + \frac{\sin^{2}(\theta)}{\cos^{2}(\theta)} = \frac{1}{\cos^{2}(\theta)}\). Using properties of exponents along with the Reciprocal and Quotient Identities, this reduces to \(1 + \tan^{2}(\theta) = \sec^{2}(\theta)\). If \(\sin(\theta) \neq 0\), we can divide both sides of the identity \(\cos^{2}(\theta) + \sin^{2}(\theta) = 1\) by \(\sin^{2}(\theta)\), apply the Reciprocal and Quotient Identities once again, and obtain \(\cot^{2}(\theta) + 1 = \csc^{2}(\theta)\). These three Pythagorean Identities are worth memorizing and they, along with some of their other common forms, are summarized in the following theorem.

- \(\cos^{2}(\theta) + \sin^{2}(\theta) = 1\).

Common Alternate Forms:

- \(1 - \sin^{2}(\theta) = \cos^{2}(\theta)\)

- \(1 - \cos^{2}(\theta) = \sin^{2}(\theta)\)

- \(1 + \tan^{2}(\theta) = \sec^{2}(\theta)\), provided \(\cos(\theta) \neq 0\).

Common Alternate Forms:

- \(\sec^{2}(\theta) - \tan^{2}(\theta) = 1\)

- \(\sec^{2}(\theta) - 1 = \tan^{2}(\theta)\)

- \(1 + \cot^{2}(\theta) = \csc^{2}(\theta)\), provided \(\sin(\theta) \neq 0\).

Common Alternate Forms:

- \(\csc^{2}(\theta) - \cot^{2}(\theta) = 1\)

- \(\csc^{2}(\theta) - 1 = \cot^{2}(\theta)\)

Verifying Identities

Trigonometric identities play an important role in not just Trigonometry, but in Calculus as well. We’ll use them in this book to find the values of the circular functions of an angle and solve equations and inequalities. In Calculus, they are needed to simplify otherwise complicated expressions. In the next example, we make good use of the Reciprocal, Quotient, and Pythagorean Identities.

Verify the following identities. Assume that all quantities are defined.

- \(\frac{1}{\csc(\theta)} = \sin(\theta)\)

- \(\tan(\theta) = \sin(\theta) \sec(\theta)\)

- \((\sec(\theta) - \tan(\theta)) (\sec(\theta) + \tan(\theta)) = 1\)

- \(\frac{\sec(\theta)}{1 - \tan(\theta)} = \frac{1}{\cos(\theta) - \sin(\theta)}\)

- \(6\sec(\theta) \tan(\theta) = \frac{3}{1-\sin(\theta)} - \frac{3}{1 + \sin(\theta)}\)

- \(\frac{\sin(\theta)}{1 - \cos(\theta)} = \frac{1 + \cos(\theta)}{\sin(\theta)}\)

Solution

In verifying identities, we typically start with the more complicated side of the equation and use known identities to transform it into the other side of the equation.

- To verify \(\frac{1}{\csc(\theta)} = \sin(\theta)\), we start with the left side. \[ \begin{array}{rclr}

\dfrac{1}{\csc(\theta)} & = & \dfrac{1}{\frac{1}{\sin(\theta)}} & \left( \text{Reciprocal Identity} \right) \\

& = & \sin(\theta) & \\

\end{array} \nonumber\] - Starting with the right hand side of \(\tan(\theta) = \sin(\theta) \sec(\theta)\), we find: \[ \begin{array}{rclr}

\sin(\theta) \sec(\theta) & = & \sin(\theta) \dfrac{1}{\cos(\theta)} & \left( \text{Reciprocal Identity} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)} & \\

& = & \tan(\theta) & \left( \text{Quotient Identity} \right) \\

\end{array} \nonumber\] - Expanding the left hand side of the equation gives: \[ \begin{array}{rclr}

(\sec(\theta) - \tan(\theta)) (\sec(\theta) + \tan(\theta)) & = & \sec^{2}(\theta) - \tan^{2}(\theta) & \left( \text{Distribution} \right) \\

& = & 1 & \left( \text{Pythagorean Identity} \right) \\

\end{array} \nonumber\] - While both sides of this identity contain fractions, the left side affords us more opportunities to use our identities.4 \[\begin{array}{rclr}

\dfrac{\sec(\theta)}{1 - \tan(\theta)} & = & \dfrac{ \dfrac{1}{\cos(\theta)}}{1 - \dfrac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)}} & \left( \text{Reciprocal and Quotient Identities} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{ \left( \dfrac{1}{\cos(\theta)} \right) }{\left( 1 - \dfrac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)} \right)} \cdot \dfrac{\cos(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)} & \left( \text{Simplifying the compound fraction} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{1}{(1)(\cos(\theta)) - \left(\dfrac{\sin(\theta)}{\cancel{\cos(\theta)}}\right)(\cancel{\cos(\theta)})} & \left( \text{Distribution} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{1}{\cos(\theta) - \sin(\theta)} & \\

\end{array}\nonumber\] which is exactly what we had set out to show. - The right hand side of the equation seems to hold more promise.\[\begin{array}{rclr}

\dfrac{3}{1-\sin(\theta)} - \dfrac{3}{1 + \sin(\theta)} & = & \dfrac{3(1 + \sin(\theta))}{(1-\sin(\theta))(1 + \sin(\theta))} - \dfrac{3(1-\sin(\theta))}{(1 + \sin(\theta))(1-\sin(\theta))} & \left( \text{Common denominators} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{3 + 3\sin(\theta)}{1 - \sin^{2}(\theta)} - \dfrac{3 - 3\sin(\theta)}{1 - \sin^{2}(\theta)} & \left( \text{Pythagorean Identity} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{(3 + 3\sin(\theta)) - (3 - 3\sin(\theta))}{1 - \sin^{2}(\theta)} & \left( \text{Adding rational expressions with like denominators} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{6 \sin(\theta)}{1 - \sin^{2}(\theta)} & \left( \text{Distribution and combine like terms} \right) \\

\end{array}\nonumber\]At this point, it is worth pausing to remind ourselves of our goal. We wish to transform this expression into \(6\sec(\theta) \tan(\theta)\). In other words, we need to get cosines in our denominator.\[\begin{array}{rclr}

\dfrac{3}{1-\sin(\theta)} - \dfrac{3}{1 + \sin(\theta)} & = & \dfrac{6 \sin(\theta)}{1 - \sin^{2}(\theta)} & \\

& = & \dfrac{6 \sin(\theta)}{\cos^{2}(\theta)} & \left( \text{Pythagorean Identity} \right) \\

& = & 6 \left(\dfrac{1}{\cos(\theta)}\right)\left( \dfrac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)}\right) & \\

& = & 6 \sec(\theta) \tan(\theta) & \left( \text{Quotient and Reciprocal Identities} \right) \\

\end{array}\nonumber\] - It is debatable which side of this identity is more complicated. One thing which stands out is that the denominator on the left hand side is \(1-\cos(\theta)\), while the numerator of the right hand side is \(1+\cos(\theta)\). This suggests the strategy of starting with the left hand side and multiplying the numerator and denominator by the quantity \(1+\cos(\theta)\):\[\begin{array}{rclr}

\dfrac{\sin(\theta)}{1 - \cos(\theta)} & = & \dfrac{\sin(\theta)}{(1 - \cos(\theta))} \cdot \dfrac{(1 + \cos(\theta))}{(1 + \cos(\theta))} & \left( \text{Multiplying numerator and denominator by the Pythagorean Conjugate of the denominator} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{\sin(\theta)(1 + \cos(\theta))}{1 - \cos^{2}(\theta)} & \left( \text{Distribution} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{\sin(\theta)(1 + \cos(\theta))}{\sin^{2}(\theta)} & \left( \text{Pythagorean Identity} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{\cancel{\sin(\theta)}(1 + \cos(\theta))}{\cancel{\sin(\theta)}\sin(\theta)} & \left( \text{Cancel like factors} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{1 + \cos(\theta)}{\sin(\theta)} & \\

\end{array}\nonumber\]

In Example \( \PageIndex{3} \) parf f above, we see that multiplying \(1-\cos(\theta)\) by \(1+\cos(\theta)\) produces a difference of squares that can be simplified to one term using the Pythagorean Identity. This is exactly the same kind of phenomenon that occurs when we multiply expressions such as \(1 - \sqrt{2}\) by \(1+\sqrt{2}\) or \(3 - 4i\) by \(3+4i\). (Can you recall instances from Algebra where we did such things?) For this reason, the quantities \((1-\cos(\theta))\) and \((1+\cos(\theta))\) are called "Pythagorean Conjugates." Below is a list of other common Pythagorean Conjugates.

- \(1 - \cos(\theta)\) and \(1+\cos(\theta)\): \((1-\cos(\theta))(1+\cos(\theta)) = 1 - \cos^{2}(\theta) = \sin^{2}(\theta)\)

- \(1-\sin(\theta)\) and \(1 + \sin(\theta)\): \((1-\sin(\theta))(1+\sin(\theta)) = 1 - \sin^{2}(\theta) = \cos^{2}(\theta)\)

- \(\sec(\theta)-1\) and \(\sec(\theta)+1\): \((\sec(\theta)-1)(\sec(\theta)+1) = \sec^{2}(\theta) - 1 = \tan^{2}(\theta)\)

- \(\sec(\theta)-\tan(\theta)\) and \(\sec(\theta)+\tan(\theta)\): \((\sec(\theta)-\tan(\theta))(\sec(\theta)+\tan(\theta)) = \sec^{2}(\theta) - \tan^{2}(\theta) = 1\)

- \(\csc(\theta)-1\) and \(\csc(\theta)+1\): \((\csc(\theta)-1)(\csc(\theta)+1) = \csc^{2}(\theta) - 1 = \cot^{2}(\theta)\)

- \(\csc(\theta)-\cot(\theta)\) and \(\csc(\theta)+\cot(\theta)\): \((\csc(\theta)-\cot(\theta))(\csc(\theta)+\cot(\theta)) = \csc^{2}(\theta) - \cot^{2}(\theta) = 1\)

Throughout the rest of your mathematical career, you will often find yourself in the position of needing to multiply the numerator and denominator by the conjugate (whether it be the complex conjugate, radical conjugate, or Pythagorean conjugate) of the denominator or numerator of the expression (just as we did in Example \( \PageIndex{3} \) part f). When doing so, it is critical to only multiply out (distribute) the conjugate expressions. Distributing the non-conjugate pieces only creates more work.

For example, look at Example \( \PageIndex{3} \) part f. There was a moment (at the very beginning) when we multiplied numerator and denominator by \( (1 + \cos(\theta)) \). The reason we chose to perform this multiplication was the denominator of the expression \( \frac{\sin(\theta)}{1 - \cos(\theta)} \). Hence, we only performed the actual distribution on the denominator and we left the numerator as \( \sin(\theta)(1 + \cos(\theta)) \). Had we distributed through in the numerator as well, we would have ended up with\[ \dfrac{\sin(\theta) + \cos(\theta) \sin(\theta)}{\sin^{2}(\theta)}, \nonumber \]and, while we could factor a sine out of the numerator and cancel it with the denominator, it would have been an extra step and, more importantly, that extra move often throws people off.

Verifying trigonometric identities requires a healthy mix of tenacity and inspiration. You will need to spend many hours struggling with them just to become proficient in the basics. Like many things in life, there is no short-cut here – there is no complete algorithm for verifying identities. Nevertheless, a summary of some strategies which may be helpful (depending on the situation) is provided below and ample practice is provided for you in the Exercises.

Strategies for Verifying Identities

- Try working on the more complicated side of the identity.

- Use the Reciprocal and Quotient Identities to write functions on one side of the identity in terms of the functions on the other side of the identity. Simplify the resulting compound fractions.

- Add rational expressions with unlike denominators by obtaining common denominators.

- Use the Pythagorean Identities to "exchange" sines and cosines, secants and tangents, cosecants and cotangents, and simplify sums or differences of squares to one term.

- Multiply numerator and denominator by Pythagorean Conjugates in order to take advantage of the Pythagorean Identities.

- If you find yourself stuck working with one side of the identity, try starting with the other side of the identity and see if you can find a way to bridge the two parts of your work.

4 Or, to put to another way, earn more partial credit if this were an exam question!

Beyond the Unit Circle

In Section 10.2, we generalized the cosine and sine functions from coordinates on the Unit Circle to coordinates on circles of radius \(r\). Using Theorem 10.2.4 in conjunction with the Pythagorean Identity, we generalize the remaining circular functions in kind.

Suppose \(Q(x,y)\) is the point on the terminal side of an angle \(\theta\) (plotted in standard position) which lies on the circle of radius \(r\), \(x^2+y^2 = r^2\). Then:

- \(\sec(\theta) = \frac{r}{x} = \frac{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}}{x}\), provided \(x \neq 0\).

- \(\csc(\theta) = \frac{r}{y} = \frac{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}}{y}\), provided \(y \neq 0\).

- \(\tan(\theta) = \frac{y}{x}\), provided \(x \neq 0\).

- \(\cot(\theta) = \frac{x}{y}\), provided \(y \neq 0\).

- Suppose the terminal side of \(\theta\), when plotted in standard position, contains the point \(Q(3,-4)\). Find the values of the six circular functions of \(\theta\).

- Suppose \(\theta\) is a Quadrant IV angle with \(\cot(\theta) = -4\). Find the values of the five remaining circular functions of \(\theta\).

Solution

- Since \(x = 3\) and \(y=-4\), \(r = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2} = \sqrt{(3)^2+(-4)^2} = \sqrt{25} = 5\). Theorem \( \PageIndex{5} \) tells us \(\cos(\theta) = \frac{3}{5}\), \(\sin(\theta) = -\frac{4}{5}\), \(\sec(\theta) = \frac{5}{3}\), \(\csc(\theta) = -\frac{5}{4}\), \(\tan(\theta) = -\frac{4}{3}\) and \(\cot(\theta) = - \frac{3}{4}\).

- In order to use Theorem \( \PageIndex{5} \), we need to find a point \(Q(x,y)\) which lies on the terminal side of \(\theta\), when \(\theta\) is plotted in standard position. We have that \(\cot(\theta) = -4 = \frac{x}{y}\), and since \(\theta\) is a Quadrant IV angle, we also know \(x>0\) and \(y< 0\). Viewing \(-4 = \frac{4}{-1}\), we may choose5 \(x = 4\) and \(y = -1\) so that \(r = \sqrt{x^2+y^2} = \sqrt{(4)^2 + (-1)^2} = \sqrt{17}\). Applying Theorem \( \PageIndex{5} \) once more, we find \(\cos(\theta) = \frac{4}{\sqrt{17}} = \frac{4 \sqrt{17}}{17}\), \(\sin(\theta) =- \frac{1}{\sqrt{17}} = -\frac{\sqrt{17}}{17}\), \(\sec(\theta) = \frac{\sqrt{17}}{4}\), \(\csc(\theta) = - \sqrt{17}\) and \(\tan(\theta) = -\frac{1}{4}\).

We may also specialize Theorem \( \PageIndex{5} \) to the case of acute angles \(\theta\) which reside in a right triangle, as visualized below.

Suppose \(\theta\) is an acute angle residing in a right triangle. If the length of the side adjacent to \(\theta\) is \(a\), the length of the side opposite \(\theta\) is \(b\), and the length of the hypotenuse is \(c\), then \[\begin{array}{llll} \tan(\theta) = \dfrac{b}{a} \;\;\;\;\;\; & \sec(\theta) = \dfrac{c}{a} \;\;\;\;\;\; & \csc(\theta) = \dfrac{c}{b} \;\;\;\;\;\; & \cot(\theta) = \dfrac{a}{b} \end{array}\nonumber\]

The following example uses Theorem \( \PageIndex{6} \) as well as the concept of an "angle of inclination." The angle of inclination (or angle of elevation) of an object refers to the angle whose initial side is some kind of base-line (say, the ground), and whose terminal side is the line-of-sight to an object above the base-line. This is represented schematically below.

The angle of inclination from the base line to the object is \( \theta \)

The angle of inclination from the base line to the object is \( \theta \)- The angle of inclination from a point on the ground 30 feet away to the top of Lakeland’s Armington Clocktower6 is \(60^{\circ}\). Find the height of the Clocktower to the nearest foot.

- In order to determine the height of a California Redwood tree, two sightings from the ground, one 200 feet directly behind the other, are made. If the angles of inclination were \(45^{\circ}\) and \(30^{\circ}\), respectively, how tall is the tree to the nearest foot?

Solution

- We can represent the problem situation using a right triangle as shown below. If we let \(h\) denote the height of the tower, then Theorem \( \PageIndex{6} \) gives \(\tan\left(60^{\circ}\right) = \frac{h}{30}\). From this we get \(h = 30 \tan\left(60^{\circ}\right) = 30 \sqrt{3} \approx 51.96\). Hence, the Clocktower is approximately \(52\) feet tall.

- Sketching the problem situation below, we find ourselves with two unknowns: the height \(h\) of the tree and the distance \(x\) from the base of the tree to the first observation point.

Finding the height of a California Redwood

Finding the height of a California RedwoodUsing Theorem \( \PageIndex{6} \), we get a pair of equations: \(\tan\left(45^{\circ}\right) = \frac{h}{x}\) and \(\tan\left(30^{\circ}\right) = \frac{h}{x+200}\). Since \(\tan\left(45^{\circ}\right) = 1\), the first equation gives \(\frac{h}{x} = 1\), or \(x = h\). Substituting this into the second equation gives \(\frac{h}{h+200} = \tan\left(30^{\circ}\right) = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}\). Clearing fractions, we get \(3h = (h+200) \sqrt{3}\). The result is a linear equation for \(h\), so we proceed to expand the right hand side and gather all the terms involving \(h\) to one side.

\[\begin{array}{rcl} 3h & = & (h+200)\sqrt{3} \\[4pt] 3h & = & h \sqrt{3} + 200 \sqrt{3} \\[4pt] 3h - h \sqrt{3} & = & 200 \sqrt{3} \\[4pt] (3-\sqrt{3}) h & = & 200 \sqrt{3} \\[4pt] h & = & \dfrac{200\sqrt{3}}{3-\sqrt{3}} \approx 273.20 \\ \end{array}\nonumber\]

Hence, the tree is approximately \(273\) feet tall.

5 We may choose any values \(x\) and \(y\) so long as \(x>0, y<0\) and \(\frac{x}{y}=-4\). For example, we could choose \(x = 8\) and \(y = −2\). The fact that all such points lie on the terminal side of \(\theta\) is a consequence of the fact that the terminal side of \(\theta\) is the portion of the line with slope \(-\frac{1}{4}\) which extends from the origin into Quadrant IV.

6 Named in honor of Raymond Q. Armington, Lakeland’s Clocktower has been a part of campus since 1972.

Domains and Ranges of the Remaining Trigonometric Functions

As we did in Section 10.2, we may consider all six circular functions as functions of real numbers. At this stage, there are three equivalent ways to define the functions \(\sec(t)\), \(\csc(t)\), \(\tan(t)\) and \(\cot(t)\) for real numbers \(t\). First, we could go through the formality of the "wrapping function" from Section 10.2 and define these functions as the appropriate ratios of \(x\) and \(y\) coordinates of points on the Unit Circle; second, we could define them by associating the real number \(t\) with the angle \(\theta = t\) radians so that the value of the trigonometric function of \(t\) coincides with that of \(\theta\); lastly, we could simply define them using the Reciprocal and Quotient Identities as combinations of the functions \(f(t) = \cos(t)\) and \(g(t) = \sin(t)\). Presently, we adopt the last approach.

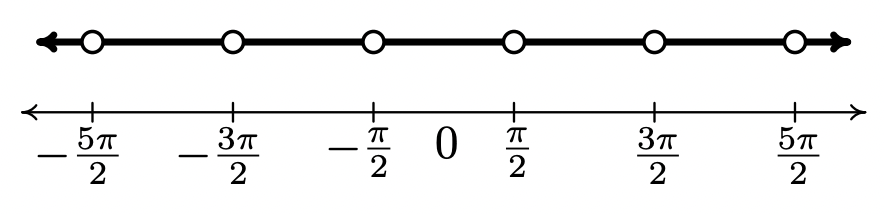

We now set about determining the domains and ranges of the remaining four circular functions. Consider the function \(F(t) = \sec(t)\) defined as \(F(t) = \sec(t) = \frac{1}{\cos(t)}\). We know \(F\) is undefined whenever \(\cos(t) = 0\). From Example 10.2.5 number 3, we know \(\cos(t) = 0\) whenever \(t = \frac{\pi}{2} + \pi k\) for integers \(k\). Hence, our domain for \(F(t) = \sec(t)\), in set builder notation is \(\left\{t: t \neq \frac{\pi}{2}+\pi k, \text { for integers } k\right\}\). To get a better understanding what set of real numbers we’re dealing with, it pays to write out and graph this set. Running through a few values of \(k\), we find the domain to be \(\{ t : t \neq \pm \frac{\pi}{2}, \, \pm \frac{3\pi}{2}, \, \pm \frac{5\pi}{2}, \, \ldots \}\). Graphing this set on the number line we get

Using interval notation to describe this set, we get \[\ldots \cup \left( -\frac{5\pi}{2}, -\frac{3\pi}{2}\right) \cup \left( -\frac{3\pi}{2}, -\frac{\pi}{2}\right) \cup \left(-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right) \cup \left(\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{3\pi}{2}\right) \cup \left(\frac{3\pi}{2}, \frac{5\pi}{2}\right) \cup \ldots\nonumber\]

This is cumbersome, to say the least! In order to write this in a more compact way, we note that from the set-builder description of the domain, the \(k\)th point excluded from the domain, which we’ll call \(x_{k}\), can be found by the formula \(x_{k} = \frac{\pi}{2} + \pi k\). (We are using sequence notation from Chapter 7.) Getting a common denominator and factoring out the \(\pi\) in the numerator, we get \(x_{k} = \frac{(2k+1)\pi}{2}\). The domain consists of the intervals determined by successive points \(x_{k}\): \(\left(x_{k}, x_{k+1}\right) = \left( \frac{(2k+1)\pi}{2}, \frac{(2k+3)\pi}{2}\right)\). In order to capture all of the intervals in the domain, \(k\) must run through all of the integers, that is, \(k = 0, \pm 1, \pm 2, \ldots\). The way we denote taking the union of infinitely many intervals like this is to use what we call in this text extended interval notation. The domain of \(F(t) = \sec(t)\) can now be written as

\[\bigcup_{k = -\infty}^{\infty} \left( \frac{(2k+1)\pi}{2}, \frac{(2k+3) \pi}{2} \right)\nonumber\]

The reader should compare this notation with summation notation introduced in Section 7.2, in particular the notation used to describe geometric series in Theorem 7.2.4. In the same way the index \(k\) in the series \[\displaystyle{\sum_{k = 1}^{\infty} a r^{k-1}}\nonumber\] can never equal the upper limit \(\infty\), but rather, ranges through all of the natural numbers, the index \(k\) in the union \[\displaystyle{\bigcup_{k = -\infty}^{\infty} \left( \frac{(2k+1)\pi}{2}, \frac{(2k+3) \pi}{2} \right)}\nonumber\] can never actually be \(\infty\) or \(-\infty\), but rather, this conveys the idea that \(k\) ranges through all of the integers.

Now that we have painstakingly determined the domain of \(F(t) = \sec(t)\), it is time to discuss the range. Once again, we appeal to the definition \(F(t) = \sec(t) = \frac{1}{\cos(t)}\). The range of \(f(t) = \cos(t)\) is \([-1,1]\), and since \(F(t) = \sec(t)\) is undefined when \(\cos(t) = 0\), we split our discussion into two cases: when \(0 < \cos(t) \leq 1\) and when \(-1 \leq \cos(t) < 0\). If \(0 < \cos(t) \leq 1\), then we can divide the inequality \(\cos(t) \leq 1\) by \(\cos(t)\) to obtain \(\sec(t) = \frac{1}{\cos(t)} \geq 1\). Moreover, using the notation introduced in Section 4.2, we have that as \(\cos(t) \rightarrow 0^{+}\), \(\sec (t)=\frac{1}{\cos (t)} \approx \frac{1}{\text { very small (+) }} \approx \text { very big }(+)\). In other words, as \(\cos(t) \rightarrow 0^{+}, \sec(t) \rightarrow \infty\). If, on the other hand, if \(-1 \leq \cos(t) < 0\), then dividing by \(\cos(t)\) causes a reversal of the inequality so that \(\sec(t) = \frac{1}{\sec(t)} \leq -1\). In this case, as \(\cos(t) \rightarrow 0^{-}\), \(\sec (t)=\frac{1}{\cos (t)} \approx \frac{1}{\text { very small }(-)} \approx \text { very big }(-)\), so that as \(\cos (t) \rightarrow 0^{-}\), we get \(\sec(t) \rightarrow -\infty\). Since \(f(t) = \cos(t)\) admits all of the values in \([-1,1]\), the function \(F(t) = \sec(t)\) admits all of the values in \((-\infty, -1] \cup [1,\infty)\). Using set-builder notation, the range of \(F(t) = \sec(t)\) can be written as \(\{u: u \leq-1 \text { or } u \geq 1\}\), or, more succinctly,7 as \(\{ u :|u| \geq 1 \}\).8 Similar arguments can be used to determine the domains and ranges of the remaining three circular functions: \(\csc(t)\), \(\tan(t)\) and \(\cot(t)\). The reader is encouraged to do so. (See the Exercises.) For now, we gather these facts into the theorem below.

- The function \(f(t) = cos(t)\)

- has domain \( \left( -\infty,\infty \right) \right)

- has range \( \left[ -1,1 \right] \)

- The function \(g(t) = sin(t)\)

- has domain \( \left( -\infty,\infty \right) \right)

- has range \( \left[ -1,1 \right] \)

- The function \(F(t) = \sec(t) = \frac{1}{\cos(t)}\)

- has domain \(\left\{t: t \neq \frac{\pi}{2}+\pi k, \text { for integers } k\right\}=\bigcup_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\left(\frac{(2 k+1) \pi}{2}, \frac{(2 k+3) \pi}{2}\right)\)

- has range \(\{ u : |u| \geq 1 \} = (-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)\)

- The function \(G(t) = \csc(t) = \frac{1}{\sin(t)}\)

- has domain \(\{t: t \neq \pi k, \text { for integers } k\}=\bigcup_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}(k \pi,(k+1) \pi)\)

- has range \(\{ u : |u| \geq 1 \} = (-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)\)

- The function \(J(t) = \tan(t) = \frac{\sin(t)}{\cos(t)}\)

- has domain \(\left\{t: t \neq \frac{\pi}{2}+\pi k, \text { for integers } k\right\}=\bigcup_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\left(\frac{(2 k+1) \pi}{2}, \frac{(2 k+3) \pi}{2}\right)\)

- has range \((-\infty, \infty)\)

- The function \(K(t) = \cot(t) = \frac{\cos(t)}{\sin(t)}\)

- has domain \(\{t: t \neq \pi k, \text { for integers } k\}=\bigcup_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}(k \pi,(k+1) \pi)\)

- has range \((-\infty, \infty)\)

We close this section with a few notes about solving equations which involve the circular functions. First, the discussion in Beyond the Unit Circle from Section 10.2 concerning solving equations applies to all six circular functions, not just \(f(t) = \cos(t)\) and \(g(t) = \sin(t)\). In particular, to solve the equation \(\cot(t) = -1\) for real numbers \(t\), we can use the same thought process we used in Example \( \PageIndex{2} \), part c to solve \(\cot(\theta) = -1\) for angles \(\theta\) in radian measure – we just need to remember to write our answers using the variable \(t\) as opposed to \(\theta\).

Next, it is critical that you know the domains and ranges of the six circular functions so that you know which equations have no solutions. For example, \(\sec(t) = \frac{1}{2}\) has no solution because \(\frac{1}{2}\) is not in the range of secant. Finally, you will need to review the notions of reference angles and coterminal angles so that you can see why \(\csc(t) = -42\) has an infinite set of solutions in Quadrant III and another infinite set of solutions in Quadrant IV.

7 Using Theorem 2.4.2 from Section 2.4.

8 Notice we have used the variable "\(u\)" as the "dummy variable" to describe the range elements. While there is no mathematical reason to do this (we are describing a set of real numbers, and, as such, could use \(t\) again) we choose \(u\) to help solidify the idea that these real numbers are the outputs from the inputs, which we have been calling \(t\).