3.1: Extrema

- Page ID

- 116589

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

|

|

Given a particular function, we are often interested in determining the largest and smallest values. This information is important in creating accurate graphs. Finding a function's maximum and minimum values is also practical because this method can solve optimization problems, such as maximizing profit, minimizing the amount of material used in manufacturing an aluminum can, or finding the maximum height a rocket can reach. This section uses derivatives to find a function's largest and smallest values.

Absolute Extrema

Consider the function \(f(x)=x^2+1\) over the interval \((−\infty,\infty)\). As \(x \to \pm \infty, f(x) \to \infty\). Therefore, the function does not have a largest value. However, since \(x^2+1 \geq 1\) for all real numbers \(x\) and \(x^2+1=1\) when \(x=0\), the function has a smallest value, \(1\), when \(x=0\). We say that \(1\) is the absolute minimum of \(f(x)=x^2+1\) and it occurs at \(x=0\). We say that \(f(x)=x^2+1\) does not have an absolute maximum (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): The given function has an absolute minimum of \(1\) at \(x=0\). The function does not have an absolute maximum.

Let \(f\) be a function defined over an interval \(I\) and let \(c \in I\). We say \(f\) has an absolute maximum on \(I\) at \(c\) if \(f(c) \geq f(x)\) for all \(x \in I\). We say \(f\) has an absolute minimum on \(I\) at \(c\) if \(f(c) \leq f(x)\) for all \(x \in I\). If \(f\) has an absolute maximum on \(I\) at \(c\) or an absolute minimum on \(I\) at \(c\), we say \(f\) has an absolute extremum on \(I\) at \(c\).

Before proceeding, let's note two important issues regarding this definition. First, the term absolute here does not refer to absolute value. An absolute extremum may be positive, negative, or zero. Second, if a function \(f\) has an absolute extremum over an interval \(I\) at \(c\), the absolute extremum is \(f(c)\). The real number \(c\) is a point in the domain at which the absolute extremum occurs. For example, consider the function \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x^2+1}\) over the interval \((−\infty,\infty)\). Since\[f(0)=1 \geq \dfrac{1}{x^2+1}=f(x) \nonumber \]for all real numbers \(x\), we say \(f\) has an absolute maximum over \((−\infty,\infty)\) at \(x=0\). The absolute maximum is \(f(0)=1\). It occurs at \(x=0\), as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2b}\).

A function may have both an absolute maximum and an absolute minimum, just one extremum, or neither. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows several functions and some of the different possibilities regarding absolute extrema ("extrema" is the plural form of extremum). However, the following theorem, called the Extreme Value Theorem, guarantees that a continuous function \(f\) over a closed interval \([a,b]\) has both an absolute maximum and an absolute minimum.

![This figure has six parts a, b, c, d, e, and f. In figure a, the line f(x) = x^3 is shown, and it is noted that it has no absolute minimum and no absolute maximum. In figure b, the line f(x) = 1/(x^2 + 1) is shown, which is near 0 for most of its length and rises to a bump at (0, 1); it has no absolute minimum, but does have an absolute maximum of 1 at x = 0. In figure c, the line f(x) = cos x is shown, which has absolute minimums of −1 at ±π, ±3π, … and absolute maximums of 1 at 0, ±2π, ±4π, …. In figure d, the piecewise function f(x) = 2 – x^2 for 0 ≤ x < 2 and x – 3 for 2 ≤ x ≤ 4 is shown, with absolute maximum of 2 at x = 0 and no absolute minimum. In figure e, the function f(x) = (x – 2)2 is shown on [1, 4], which has absolute maximum of 4 at x = 4 and absolute minimum of 0 at x = 2. In figure f, the function f(x) = x/(2 − x) is shown on [0, 2), with an absolute minimum of 0 at x = 0 and no absolute maximum.](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/2406/CNX_Calc_Figure_04_03_010.jpeg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=615&height=600)

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Graphs (a), (b), and (c) show several possibilities for absolute extrema for functions with a domain of \((−\infty,\infty).\) Graphs (d), (e), and (f) show several possibilities for absolute extrema for functions with a domain that is a bounded interval.

If \(f\) is a continuous function over the closed interval \([a,b]\), then there is a point in \([a,b]\) at which \(f\) has an absolute maximum over \([a,b]\) and there is a point in \([a,b]\) at which \(f\) has an absolute minimum over \([a,b]\).

The proof of the Extreme Value Theorem is beyond the scope of this text. Typically, it is proved in a course on Real Analysis. There are a couple of key points to note about the statement of this theorem. To apply the Extreme Value Theorem, the function must be continuous over a closed interval. Suppose the interval \(I\) is open, or the function has even one point of discontinuity. In that case, the function may not have an absolute maximum or absolute minimum over \(I\).

For example, consider the functions shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2d}\), \( \PageIndex{ 2e } \), and \( \PageIndex{ 2f } \). All three of these functions are defined over closed intervals. However, the function in graph \( \PageIndex{ 2e } \) is the only one with both an absolute maximum and an absolute minimum over its domain. The Extreme Value Theorem cannot be applied to the functions in graphs \( \PageIndex{ 2d } \) and \( \PageIndex{ 2f } \) because neither of these functions is continuous over a closed interval. Although the function in graph \( \PageIndex{ 2d } \) is defined over the closed interval \([0,4]\), the function is discontinuous at \(x=2\). The function has an absolute maximum over the closed interval \([0,4]\) but does not have an absolute minimum. The function in graph \( \PageIndex{ 2f } \) is continuous over the half-open interval \([0,2)\), but is not defined at \(x=2\), and therefore is not continuous over a closed interval. The function has an absolute minimum over \([0,2)\) but does not have an absolute maximum over \([0,2)\). These two graphs illustrate why a function over a closed interval may fail to have an absolute maximum and/or minimum.

The Extreme Value Theorem only applies to functions that are continuous over a closed interval \([a,b]\).

Before looking at how to find absolute extrema, let's examine the related concept of local extrema. This idea is useful in determining where absolute extrema occur.

Local Extrema and Critical Numbers

Consider the function \(f\) shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). The graph can be described as two mountains with a valley in the middle. The absolute maximum value of the function occurs at the higher peak, at \(x=2\). However, \(x=0\) is also a point of interest. Although \(f(0)\) is not the largest value of \(f\), the value \(f(0)\) is larger than \(f(x)\) for all \(x\) near \(0\). We say \(f\) has a local maximum (or relative maximum) at \(x=0\). Similarly, the function \(f\) does not have an absolute minimum, but it does have a local minimum (or relative minimum) at \(x=1\) because \(f(1)\) is less than \(f(x)\) for \(x\) near 1.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): This function \(f\) has two local maxima and one local minimum. The local maximum at \(x=2\) is also the absolute maximum.

A function \(f\) has a local maximum at \(c\) if there exists an open interval \(I\) containing \(c\) such that \(I\) is contained in the domain of \(f\) and \(f(c) \geq f(x)\) for all \(x \in I\). A function \(f\) has a local minimum at \(c\) if there exists an open interval \(I\) containing \(c\) such that \(I\) is contained in the domain of \(f\) and \(f(c) \leq f(x)\) for all \(x \in I\). A function \(f\) has a local extremum at \(c\) if \(f\) has a local maximum at \(c\) or \(f\) has a local minimum at \(c\).

Note that if \(f\) has an absolute extremum at \(c\) and \(f\) is defined over an interval containing \(c\), then \(f(c)\) is also considered a local extremum.

Local extrema require the function to be defined in a neighborhood containing \(c\). That is, the function must be defined on both sides of \(c\) for the possibility of a local extremum at \(c\). Hence, endpoints of a function's domain are never considered local extrema, even if they are absolute extrema.

Given the graph of a function \(f\), it is sometimes easy to see where a local maximum or local minimum occurs. However, since the interesting features on the graph of a function may not be visible because they occur at a tiny scale, we might miss out on seeing these local extrema. Also, we may not have a graph of the function. In these cases, how can we use a formula for a function to determine where these extrema occur?

To answer this question, let’s look at Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) again. The local extrema occur at \(x=0\), \(x=1\), and \(x=2\). Notice that at \(x=0\) and \(x=1\), \(f^{\prime}(x)=0\). At \(x=2\), the derivative \(f^{\prime}(x)\) does not exist, since the function \(f\) has a corner there. In fact, if \(f\) has a local extremum at a point \((c, f(c))\), the derivative \(f^{\prime}(c)\) must satisfy one of the following conditions: either \(f^{\prime}(c)=0\) or \(f^{\prime}(c)\) is undefined. Such a value \(c\) is known as a critical number, and the corresponding point \( (c, f(c)) \) is called a critical point. Critical numbers (and, therefore, critical points) are important in finding extreme values for functions.

Let \(c\) be an interior point in the domain of \(f\). We say that \(c\) is a critical number of \(f\) if \(f^{\prime}(c)=0\) or \(f^{\prime}(c)\) is undefined. The corresponding point, \((c, f(c))\), is called a critical point.

On the Cartesian coordinate system, the notation \((a,f(a))\) is used to reference a point. It is definitely not a number nor is it a value. In fact, we refer to \(f(a)\) as the value of the function \(f\) at the number \(a\).

If you are okay with those previous statements, then you should be fine with the distinction between a critical point, \((a,f(a))\), the critical number, \(x = a\), and the critical value, \(f(a)\).

It is unfortunate that most authors blur the line between these definitions and call \(x = a\) a critical point. In this text, I endeavor to be consistent with my language.

As mentioned earlier, if \(f\) has a local extremum at \(x=c\), then \(c\) must be a critical number of \(f\). This fact is known as Fermat’s Theorem.

If \(f\) has a local extremum at \(c\) and \(f\) is differentiable at \(c\), then \(f^{\prime}(c)=0.\)

- Proof

-

Suppose \(f\) has a local extremum at \(c\) and \(f\) is differentiable at \(c\). Without loss of generality, suppose the local extremum at \(c\) is a local maximum (the case in which \(f\) has a local minimum at \(c\) can be handled similarly). There then exists an open interval I such that \(f(c) \geq f(x)\) for all \(x \in I\). Since \(f\) is differentiable at \(c\), we know that\[f^{\prime}(c)=\lim_{x \to c}\dfrac{f(x)−f(c)}{x−c}. \nonumber \]Since this limit exists, both one-sided limits also exist and are equal \(f^{\prime}(c)\). Therefore,\[f^{\prime}(c)=\lim_{x \to c^+}\dfrac{f(x)−f(c)}{x−c,}\label{FermatEqn2} \]and\[f^{\prime}(c)=\lim_{x \to c^−}\dfrac{f(x)−f(c)}{x−c}. \nonumber \]Since \(f(c)\) is a local maximum, we see that \(f(x)−f(c) \leq 0\) for \(x\) near \(c\). Therefore, for \(x\) near \(c\) (but \(x>c\)), we have \(\frac{f(x)−f(c)}{x−c} \leq 0\). From Equation \ref{FermatEqn2} we conclude that \(f^{\prime}(c) \leq 0\). Similarly, it can be shown that \(f^{\prime}(c) \geq 0.\) Therefore, \(f^{\prime}(c)=0.\)

Q.E.D.

From Fermat's Theorem, we conclude the following corollary.

If \(f\) has a local extremum at \(c\), then either \(f^{\prime}(c)=0\) or \(f^{\prime}(c)\) is undefined.

In other words, local extrema can only occur at critical points.

Fermat's Theorem does not claim that a function \(f\) must have a local extremum at a critical point. Rather, it states that critical points are candidates for local extrema.

The cautionary statement above needs some explanation. Consider the function \(f(x)=x^3\). We have \(f^{\prime}(x)=3x^2=0\) when \(x=0\). Therefore, \(x=0\) is a critical number. However, \(f(x)=x^3\) is increasing over \((−\infty,\infty)\), and thus \(f\) does not have a local extremum at \(x=0\).

In Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\), we see several different possibilities for critical points. In some cases, the functions have local extrema at critical points. In contrast, in other cases, the functions do not. Note that these graphs do not show all possibilities for the behavior of a function at a critical point.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4a - e}\): A function \(f\) has a critical number at \(c\) if \(f^{\prime}(c)=0\) or \(f^{\prime}(c)\) is undefined. A function may or may not have a local extremum at a critical number.

Later in this chapter, we look at analytical methods for determining whether a function has a local extremum at a critical point. For now, let's turn our attention to finding critical points. We will use graphical observations to determine whether a critical point is associated with a local extremum.

For each of the following functions, find all critical numbers. Use a graphing utility to determine whether the function has a local extremum at each critical number.

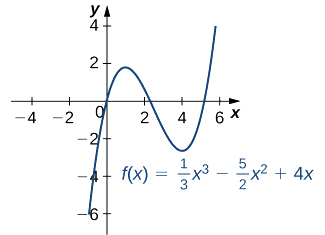

- \(f(x)=\frac{1}{3}x^3−\frac{5}{2}x^2+4x\)

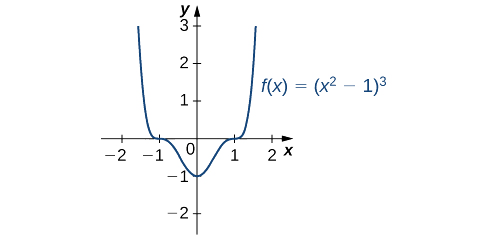

- \(f(x)=(x^2−1)^3\)

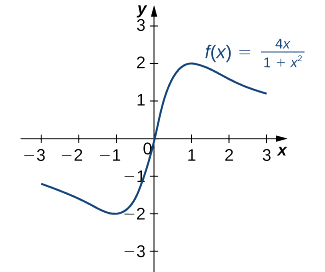

- \(f(x)=\frac{4x}{1+x^2}\)

- Solutions

-

a. The derivative \(f^{\prime}(x)=x^2−5x+4\) is defined for all real numbers \(x\). Therefore, we only need to find the values for \(x\) where \(f^{\prime}(x)=0\). Since \(f^{\prime}(x)=x^2−5x+4=(x−4)(x−1)\), the critical numbers are \(x=1\) and \(x=4.\) From the graph of \(f\) in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\), we see that \(f\) has a local maximum at \(x=1\) and a local minimum at \(x=4\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): This function has a local maximum and a local minimum.b. Using the Chain Rule, we see the derivative is\[f^{\prime}(x)=3(x^2−1)^2(2x)=6x(x^2−1)^2.\nonumber\]Therefore, \(f\) has critical points when \(x=0\) and when \(x^2−1=0\). We conclude that the critical numbers are \(x=0\), and \(x = \pm 1\). From the graph of \(f\) in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), we see that \(f\) has a local (and absolute) minimum at \(x=0\), but does not have a local extrema at \(x=1\) and \(x=−1\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): This function has three critical numbers: \(x=0\), \(x=1\), and \(x=−1\). The function has a local (and absolute) minimum at \(x=0\) but does not have extrema at the other two critical points.c. By the Quotient Rule, we see that the derivative is\[f^{\prime}(x)=\dfrac{4(1+x^2)−4x(2x)}{(1+x^2)^2}=\dfrac{4−4x^2}{(1+x^2)^2}.\nonumber\]The derivative is defined everywhere. Therefore, we only need to find values for \(x\) where \(f^{\prime}(x)=0\). Solving \(f^{\prime}(x)=0\), we see that \(4−4x^2=0\), which implies \(x= \pm 1\). Therefore, the critical numbers are \(x= \pm 1\). From the graph of \(f\) in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\), we see that f has an absolute maximum at \(x=1\) and an absolute minimum at \(x=−1\). Hence, \(f\) has a local maximum at \(x=1\) and a local minimum at \(x=−1\). (Note that if \(f\) has an absolute extremum over an interval \(I\) at a point \(c\) that is not an endpoint of \(I\), then \(f\) has a local extremum at \(c.)\)

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): This function has an absolute maximum and minimum.

Find all critical numbers for \(f(x)=x^3−\frac{1}{2}x^2−2x+1.\)

- Answer

-

\(x=\frac{−2}{3}, x=1\)

Locating Absolute Extrema

The Extreme Value Theorem states that a continuous function over a closed interval attains an absolute maximum and minimum. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows that one or both of these absolute extrema could occur at an endpoint. If an absolute extremum does not occur at an endpoint, however, it must occur at an interior point, in which case the absolute extremum is a local extremum. Therefore, by Fermat's Theorem, the interior point point \((c,f(c))\) at which the local extremum occurs must be a critical point. We summarize this result in the following theorem.

Let \(f\) be a continuous function over a closed interval \(I\). The absolute maximum of \(f\) over \(I\) and the absolute minimum of \(f\) over \(I\) must occur at endpoints of \(I\) or at critical points of \(f\) in the interior of \(I\).

Therefore, when finding the absolute extrema of a given function defined over a closed interval, we evaluate the function at the endpoints of the interval. These will be candidates for absolute extrema. In addition, we determine the critical points. The critical values (the values of the function at the critical numbers) will also be candidates for absolute extrema. The largest of these function values will be the absolute maximum of the function on the given interval, and the least will be the absolute minimum.

Now, let's use this strategy to find the absolute maximum and minimum values for continuous functions.

For each function, find the absolute maximum and minimum over the specified interval and state where those values occur.

- \(f(x)=−x^2+3x−2\) over \([1,3].\)

- \(f(x)=x^2−3x^{2/3}\) over \([0,2]\).

- Solutions

-

- Evaluate \(f\) at the endpoints \(x=1\) and \(x=3\).\[f(1)=0 \quad \text{and} \quad f(3)=−2\nonumber\]Since \(f^{\prime}(x)=−2x+3\), \(f^{\prime}\) is defined for all real numbers \(x\). Hence, there are no critical points where the derivative is undefined. It remains to check where \(f^{\prime}(x)=0\). Since \(f^{\prime}(x)=−2x+3=0 \) at \(x=\frac{3}{2}\) and \(\frac{3}{2}\) is in the interval \([1,3]\), \(f(\frac{3}{2})\) is a candidate for an absolute extremum of \(f\) over \([1,3]\). We evaluate \(f(\frac{3}{2})\) and find\[f\left(\dfrac{3}{2}\right)=\dfrac{1}{4}.\nonumber\]We then set up the following table to compare the functions values we found.

From the table, we find that the absolute maximum of \(f\) over the interval \([1, 3]\) is \(\frac{1}{4}\), and it occurs at \(x=\frac{3}{2}\). The absolute minimum of \(f\) over the interval \([1, 3]\) is \(−2\), and it occurs at \(x=3\) as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\).\(x\) \(f(x)\) Conclusion \(1\) \(0\) \(\frac{3}{2}\) \(\frac{1}{4}\) Absolute maximum \(3\) \(−2\) Absolute minimum

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): This function has both an absolute maximum and an absolute minimum. - Evaluate \(f\) at the endpoints \(x=0\) and \(x=2\).\[f(0)=0 \quad \text{and} \quad f(2)=4−3\left(2\right)^{2/3} \approx −0.762\nonumber\]The derivative of \(f\) is given by\[f^{\prime}(x)=2x−\dfrac{2}{x^{1/3}}=\dfrac{2x^{4/3}−2}{x^{1/3}}\nonumber\]for \(x \neq 0\). The derivative is zero when \(2x^{4/3}−2=0\), which implies \(x= \pm 1\). The derivative is undefined at \(x=0\). Therefore, the critical numbers of \(f\) are \(x=0\), \(1\), and \(−1\). We already evaluated \(f(0)\). The point \(x=−1\) is not in the interval of interest, so we need only evaluate \(f(1)\). We find that \(f(1)=−2\). Finally, we compare the values in the following table.

We conclude that the absolute maximum of \(f\) over the interval \([0, 2]\) is zero, and it occurs at \(x=0\). The absolute minimum is \(−2,\) and it occurs at \(x=1\) as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\).\(x\) \(f(x)\) Conclusion \(0\) \(0\) Absolute maximum \(1\) \(−2\) Absolute minimum \(2\) \(−0.762\)

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): This function has an absolute maximum at an endpoint of the interval.

- Evaluate \(f\) at the endpoints \(x=1\) and \(x=3\).\[f(1)=0 \quad \text{and} \quad f(3)=−2\nonumber\]Since \(f^{\prime}(x)=−2x+3\), \(f^{\prime}\) is defined for all real numbers \(x\). Hence, there are no critical points where the derivative is undefined. It remains to check where \(f^{\prime}(x)=0\). Since \(f^{\prime}(x)=−2x+3=0 \) at \(x=\frac{3}{2}\) and \(\frac{3}{2}\) is in the interval \([1,3]\), \(f(\frac{3}{2})\) is a candidate for an absolute extremum of \(f\) over \([1,3]\). We evaluate \(f(\frac{3}{2})\) and find\[f\left(\dfrac{3}{2}\right)=\dfrac{1}{4}.\nonumber\]We then set up the following table to compare the functions values we found.

Find the absolute maximum and absolute minimum of \(f(x)=x^2−4x+3\) over the interval \([1,4]\).

- Answer

-

The absolute maximum is \(3\) and it occurs at \(x=4\). The absolute minimum is \(−1\) and it occurs at \(x=2\).

At this point, we know how to locate absolute extrema for continuous functions over closed intervals. We have also defined local extrema and determined that if a function \(f\) has a local extremum at a number \(c\), then \(c\) must be a critical number of \(f\). However, \(c\) being a critical number is not a sufficient condition for \(f\) to have a local extremum at \(c\). Later in this chapter, we show how to determine whether a function has a local extremum at a critical point. First, however, we need to introduce the Mean Value Theorem, which will help as we analyze the behavior of the graph of a function.