1.5: Active Learning from Reading

- Last updated

-

Mar 15, 2022

-

Save as PDF

-

As with learning from lectures and discussions, the learning of information and skills presented in readings, texts, and written text from a Web site should be viewed as a process: preparation to take in the new information, the act of taking in the new information, and then reviewing the information so that it is later accessible (recalled from memory) to use for a project, paper, or test.

Students who simply start and finish a reading with no further actions taken are really wasting their time. Reading a text needs to be approached properly in order to ensure comprehension and retention of the information. Planning for an active reading session by engaging in the “before reading” activities facilitates an active mindset to the reading session and discourages “auto-pilot reading” that results in scanning of the words but no real careful thought about what is being said.

Preparing for class by reading assigned texts related to the lecture material is extremely important to optimize the lecture experience. If you have a professor who tends to lecture at a fast pace, you have the foundational information and only need to focus on writing down unfamiliar information. If your professor expects class participation in discussions or utilizes active classroom techniques, such as case studies, small group activities and discussions, simulations, or demonstrations, you will understand what is happening and be able to contribute to the learning experience. Marking or highlighting your text for main ideas while reading not only keeps your mind focused on the reading but also serves to prepare you for easier exam review.

Table 5-3. Effective Techniques for Reading

| Before Reading |

During Reading |

After Reading |

| Preview the reading headings to get a “big picture” of the outline of the reading. Look at the pictures and figures. Check out the bold and italicized words. |

As you are reading, seek out the answers to the questions that the reading or you generated rather than passively scanning the words. |

Take reading notes from the highlighted material from the text. Utilize visual organizers and summaries to capture information. Revisit the informational box on “Note-Taking Methods: What Is Right for You?” and visit “Visualize Your information and “Cram Cards for Long-term Review.” |

| Preview any questions that the chapter may offer so that you can actively seek answers to those questions. |

Monitor your concentration and comprehension. After each paragraph, ask yourself, “What was the main point of that paragraph?” After each section, summarize what you have read. |

Answer the questions that a the reading may have provided or that you developed. Reread sections in which you remember little information. |

| Turn text headings into questions so that you can actively seek answers to those questions. Jot those questions down in the margin of the text or in your notes if you plan to take reading notes. |

Mark your text. Highlight the main idea of a paragraph or write down the main idea of a paragraph in your notes. If you cannot mark your text, take reading notes on the main ideas. Refer to the informational box called “In Search of Main Ideas” for more information |

Integrate your reading notes and lecture/discussion notes into one location for easier review for an exam. |

| Plan for a high energy time of the day to read. Consider breaking up a long reading assignment into multiple, shorter reading sessions. |

Look up the definitions to words that you do not understand to help build your vocabulary and facilitate understanding of the topic. |

Discuss readings with classmates on a regular basis. Take turns explaining to each other sections of the reading. Ask and answer reading questions. Jot down questions that are unclear to the study group to ask the professor in class or during office hours. |

| Be sure you have your materials ready for reading: text, notebook paper, writing utensils, high-lighters, charged laptop, etc. |

|

|

Adapted from Dembo and Seli (2008) and Downing (2008).

In Search of Main Ideas

Some students do not actively take notes or mark their readings and texts because they determine it is a lot of extra work to write down so much information. However, the problem is that students are usually writing down too much information and not really cluing in to the main ideas. Here are some tips for identifying the main ideas when reading:

- The Table of Contents and chapter outlines provide a broad view of the main points that will be covered in a reading. Flesh out the outlines that are already provided for you.

- Oftentimes in a textbook, the main idea is the first or last sentence of a paragraph. If it is not the first or the last sentence, then look back at the entire paragraph to see what the overall issue seems to be. Look for the overall pat- terns of your textbooks.

- Titles, headings, and subheadings announce the major subject. Make these headings into questions, and the answers to the questions will likely be the main ideas.

- Bold and italic words point to a main idea or key concept that you need to understand.

- Repetition of key words or phrases throughout the text point to a main idea.

- Chapter questions at the end of the chapter are about the main ideas of the text. Answer those questions and you will identify your main ideas.

- Summaries presented at the end of the chapter also tend to restate the main ideas briefly. Flesh these ideas out with some supporting ideas, and you would have a good view of the entire chapter.

- Stop and look at the visuals—pictures, diagrams, tables, etc. Oftentimes, the message depicted in the graph or picture is typically a main idea.

- Detailed statistics, several examples in a row, and other details often signal that a main idea is being clarified, proven, supported, etc. Track back or ahead to find the main idea they are trying to illustrate.

- Text that includes bullet points, numbering, or sequences is often a main idea.

- Look for organizational patterns in the reading that might highlight the main ideas. For instance, are two issues being compared or contrasted? What was the effect of a certain event? Are problems and various solutions being presented? Is there a timeline of events that is important?

- Be intentional about searching for the main ideas. Ask yourself at the end of each section or paragraph, “What is the point?” or “What is it that the author wants me to know?”

- If you are reading a narrative, ask yourself questions like, “Who are the main characters?” “Why is this character important to this story?” “Why did the author chose to tell this part of the story?”

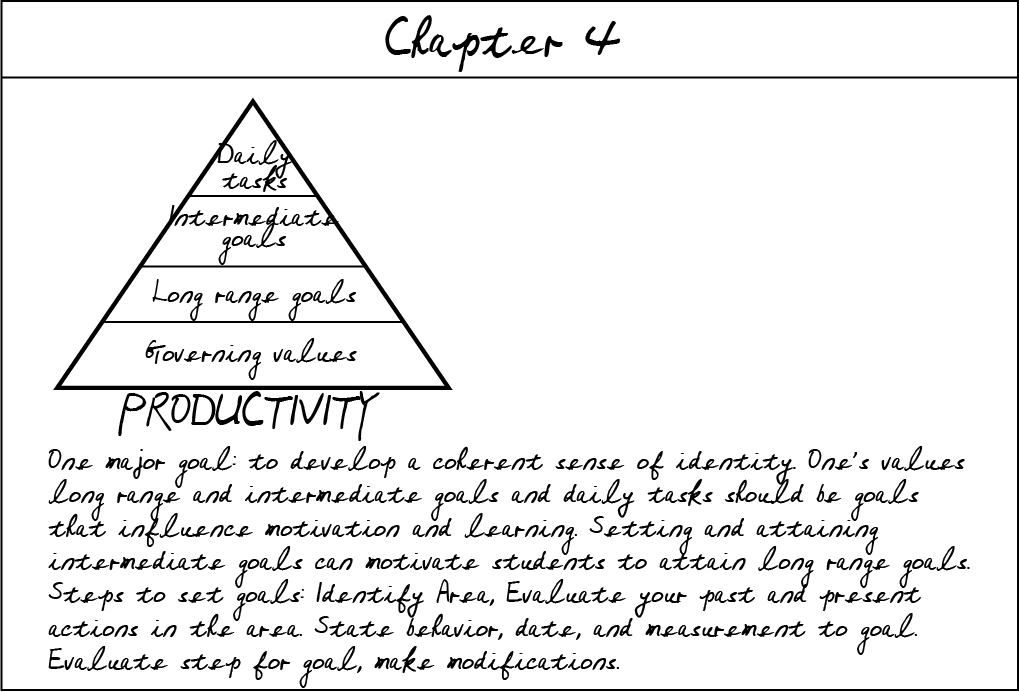

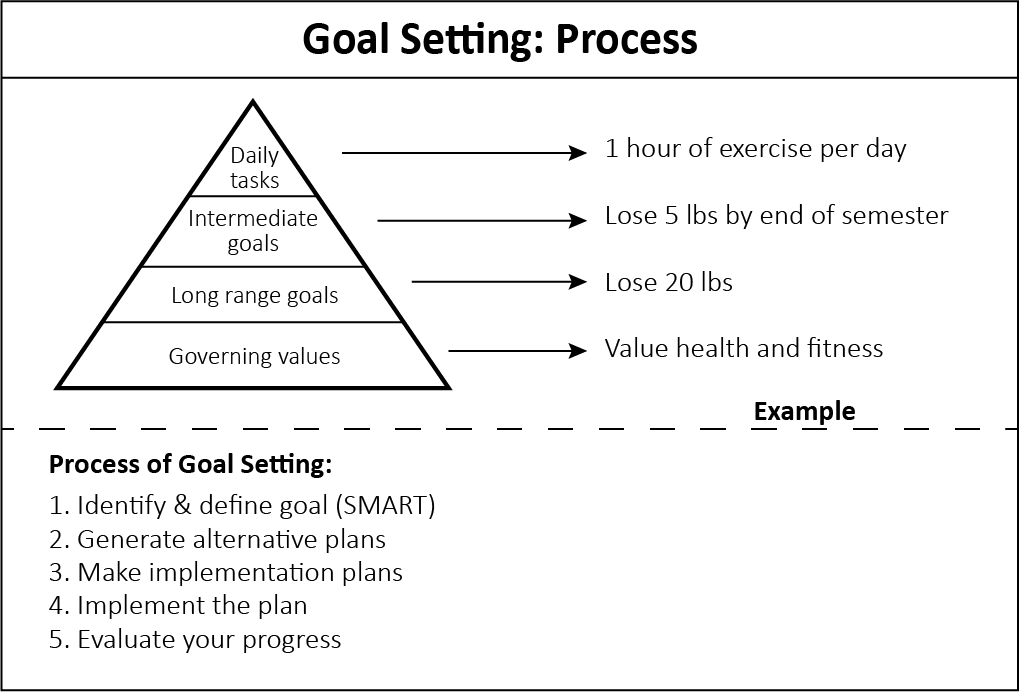

Finally, taking the time to think critically about the reading you have done further solidifies that information in your memory and can serve to prepare you for exam review. Summarizing material using visual organizers (refer to informational box “Visualize Your Information” and Figure 5-1) moves your thinking from low levels of thinking to high levels of thinking on Bloom’s Taxonomy. Integrating text and lecture notes and discussing readings with your classmates and professor promotes memory storage of that information and thinking at higher levels as well.

Visualize Your Information

Summarizing main ideas of the readings or lectures can be difficult without the right tools. Visual organizers can help students condense important information into visual diagrams that can be easily reviewed for exams or help organize a writing assignment. Muskingum College’s Center for Advancement and Learning (n.d.) hosts a useful Web site that summarizes and provides examples of various visual organizers (a.k.a. Information Organization Strategies) at

muskingum.edu/~cal/database/g...anization.html (Web site wants username and password now.)

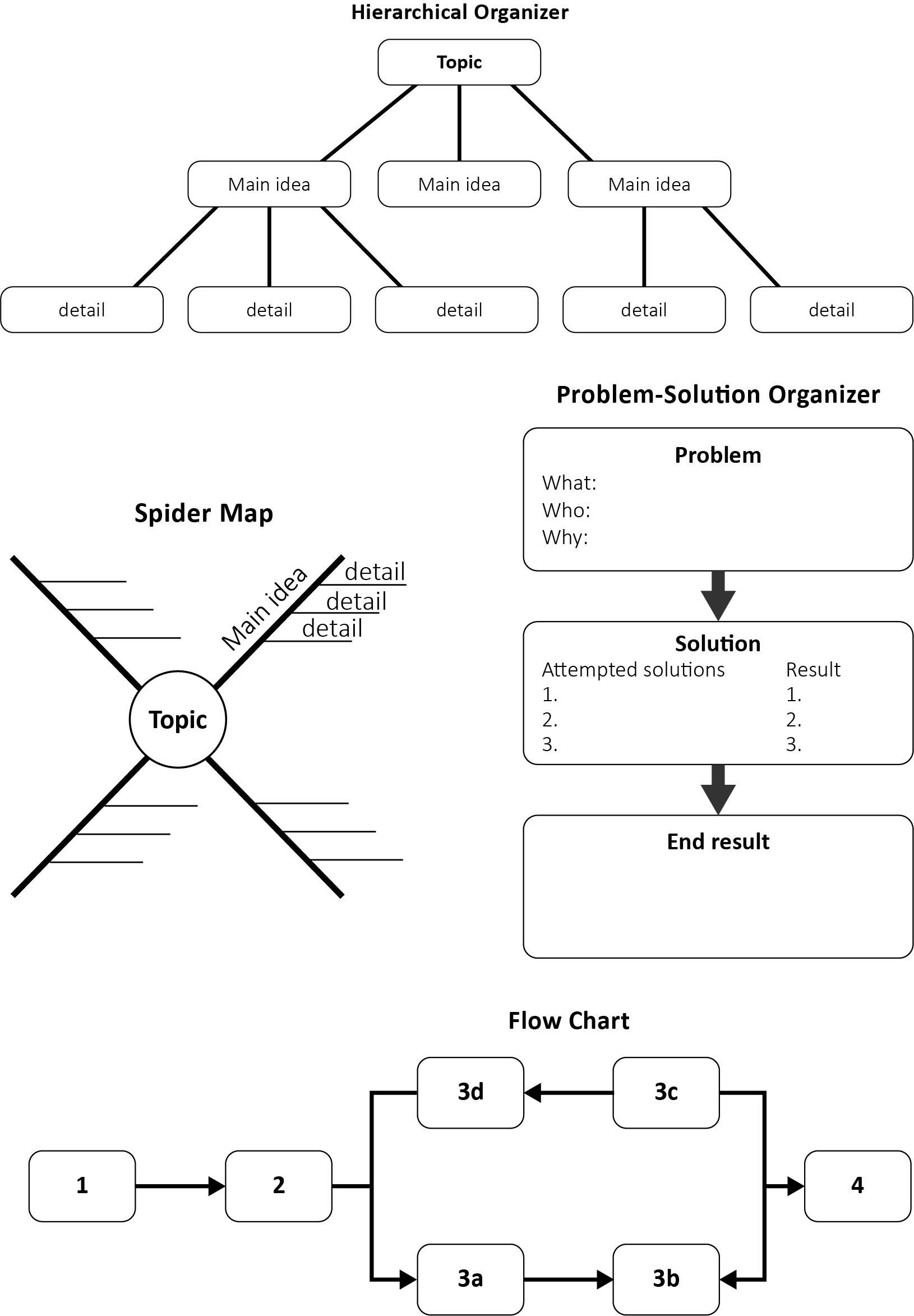

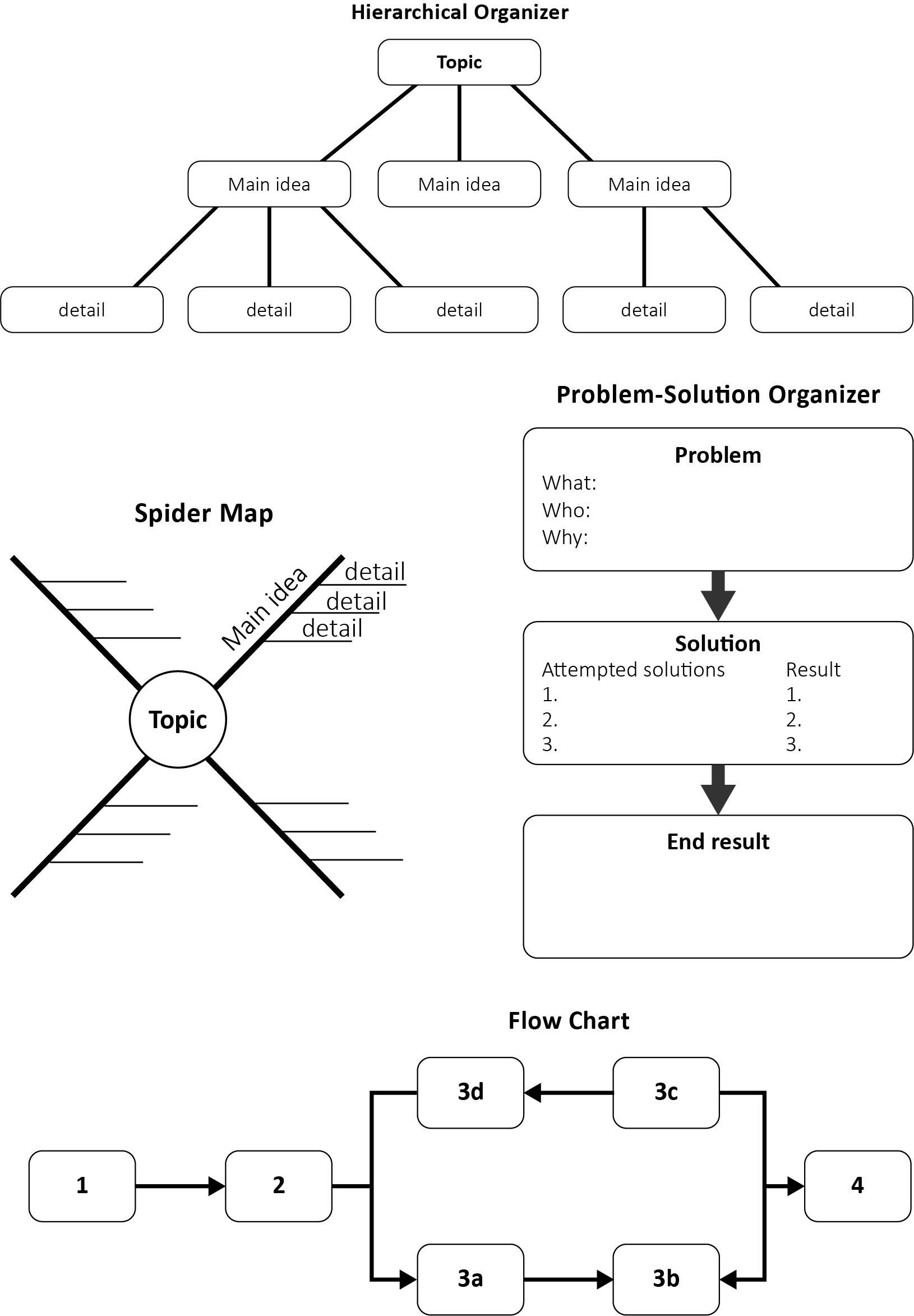

Consider how you might be able to apply several pages of text to a simple flowchart, hierarchical organizer, comparison-contrast organizer, spider map, etc. (See Figure 5-1.)

An additional benefit of using visual organizers is that you are thinking about the material at a deeper level as you identify the proper visual tool and apply the information. While at first it may take more time to determine the proper tool, it will get easier with practice and become second nature.

Activity 5-2

Utilizing what you have learned from the informational boxes “In Search of Main Ideas” and “Visualize Your Information,” select a text chapter or a week of class notes and create some visual organizers that summarize the main ideas of that material. Ask a classmate to share in the same exercise and compare your work in a critical manner. What have you learned from this exercise and each other?

Figure 5-1. Examples of visual organizers

Source: Muskingum College’s Center for Advancement and Learning (n.d)

Cram Cards for Long-term Review

The use of “cram” in cram cards is deceiving. Cram cards are a study tool that promote the active learning of reading or lecture notes and allows for the easy and portable review of material over a longer period of time, therefore promoting later recall. It is a technique that will take some practice to hone your skills in selecting main ideas, but students who use cram cards indicate it is well worth their time.

Tips for Writing Cram Cards:

- Use 4 x 6 index cards (3 x 5 size tends to be too small)—some enthusiasts will even use the colored index cards for different sources of information (i.e., notes versus text reading) or topics (e.g., blue for English and green for Biology).

- Make one cram card per major concept or main idea.

- Do not simply take notes on the card; capture a summary of the main ideas maintaining the proper relationships of the concepts.

- Write the information in your own words.

- Include book examples or provide real-life examples for difficult concepts.

- Include key words.

- Be sure to write legibly.

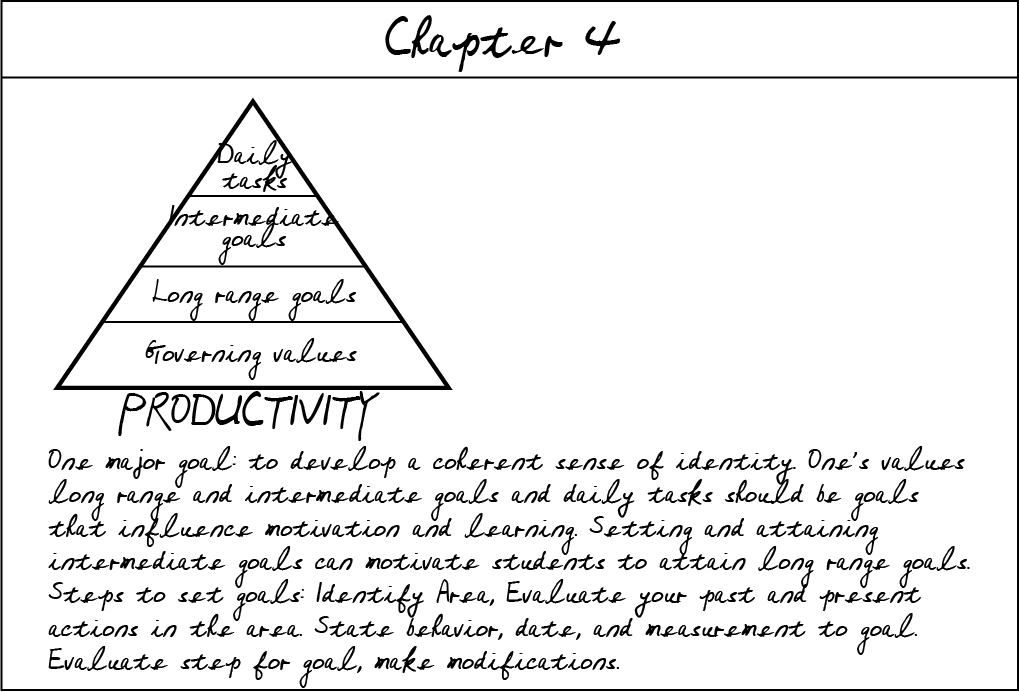

Example of a Bad Cram Card

Example of a Good Cram Card