5.3: Applications of Trigonometry - Area

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 69161

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Focus Questions

The following questions are meant to guide our study of the material in this section. After studying this section, we should understand the concepts motivated by these questions and be able to write precise, coherent answers to these questions.

- How do we use the Law of Sines and the Law of Cosines to help solve applied problems that involve triangles?

- How do we determine the area of a triangle?

- What is Heron’s Law for the area of a triangle?

In Section 3.2, we used right triangles to solve some applied problems. It should then be no surprise that we can use the Law of Sines and the Law of Cosines to solve applied problems involving triangles that are not right triangles.

In most problems, we will first get a rough diagram or picture showing the triangle or triangles involved in the problem. We then need to label the known quantities. Once that is done, we can see if there is enough information to use the Law of Sines or the Law of Cosines. Remember that each of these laws involves four quantities. If we know the value of three of those four quantities, we can use that law to determine the fourth quantity.

We begin with the example in Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\). The solution of this problem involved some complicated work with right triangles and some algebra. We will now solve this problem using the results from Section 3.3.

Example \(\PageIndex{0}\): Height to the Top of a Flagpole

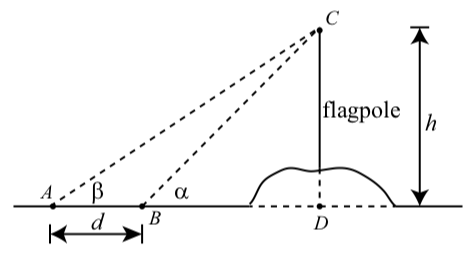

Suppose that the flagpole sits on top a hill and that we cannot directly measure the length of the shadow of the flagpole as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Some quantities have been labeled in the diagram. Angles \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are angles of elevation to the top of the flagpole from two different points on level ground. These points are \(d\) feet apart and directly in line with the flagpole. The problem is to determine \(h\), the height from level ground to the top of the flagpole. The following measurements have been recorded.

\[\alpha = 43.2^\circ\]

\[\beta = 34.7^\circ\]

\[d = 22.75feet\]

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Flagpole on a hill

We notice that if we knew either length \(BC\) or \(BD\) in \(\triangle BDC\), then we could use right triangle trigonometry to determine the length \(BC\), which is equal to h. Now look at \(\triangle ABC\). We are given one angle \(\beta\). However, we also know the measure of angle \(\alpha\). Because they form a straight angle, we have \[\angle ABC + \alpha = 180^\circ\]

Hence, \[\angle ABC = 180^\circ - 43.2^\circ = 136.8^\circ\]. We now know two angles in \(\triangle ABC\) and hence, we can determine the third angle as follows: \[\beta + \angle ABC + \angle ACB = 180^\circ\] \[34.7^\circ + 136.8^\circ + \angle ACB = 180^\circ\] \[\angle ACB = 8.5^\circ\]

We now know all angles in \(\triangle ABC\) and the length of one side. We can use the Law of Sines. We have

\[\dfrac{AC}{\sin(34.7^\circ)} = \dfrac{22.75^\circ}{\sin(8.5^\circ)}\]

\[AC = \dfrac{22.75\sin(34.7^\circ)}{\sin(8.5^\circ)} \approx 87.620\]

We can now use the right triangle \(\triangle BDC\) to determine \(h\) as follows:

\[\dfrac{h}{AC} = \sin(43.2^\circ)\]

\[h = AC\cdot \sin(43.2^\circ) \approx 59.980\]

So the top of the flagpole is 59.980 feet above the ground. This is the same answer we obtained in Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

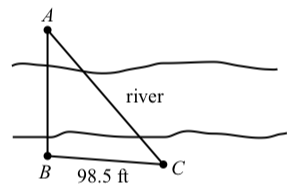

A bridge is to be built across a river. The bridge will go from point \(A\) to point \(B\) in the diagram on the right. Using a transit (an instrument to mea- sure angles), a surveyor measures angle \(ABC\) to be \(94.2^\circ\) and measures angle \(BCA\) to be \(48.5^\circ\). In addition, the distance from \(B\) to \(C\) is measured to be 98.5 feet. How long will the bridge from point \(B\) to point \(A\) be?

- Answer

-

We first note that \(\angle{BAC} = 180^\circ - 94.2^\circ - 48.5^\circ\) and so \(\angle{BAC} = 37.3^\circ\). We can then use the Law of Sines to determine the length from \(A\) to \(B\) as follows:

\[\dfrac{AB}{\sin(48.5^\circ)} = \dfrac{98.5}{\sin(37.3^\circ)}\]

\[AB = \dfrac{98.5\sin(48.5^\circ)}{\sin(37.3^\circ)}\]

\[AB \approx 121.7\]

The bridge from point \(B\) to point \(A\) will be approximately \(121.7\) feet long.

Area of a Triangle

We will now develop a few different ways to calculate the area of a triangle. Perhaps the most familiar formula for the area is the following:

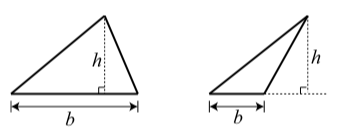

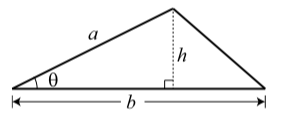

The triangles in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) illustrate the use of the variables in this formula.

The area \(A\) of a triangle is \[A = \dfrac{1}{2}bh.\]

where \(b\) is the length of the base of a triangle and \(h\) is the length of the altitude that is perpendicular to that base.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Diagrams for the Formula for the Area of a Triangle

A proof of this formula for the area of a triangle depends on the formula for the area of a parallelogram and is included in Appendix C.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

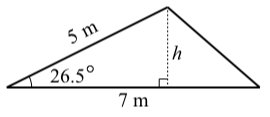

Suppose that the length of two sides of a triangle are \(5\) meters and \(7\) meters and that the angle formed by these two sides is \(26.5^\circ\). See the diagram on the right.

For this problem, we are using the side of length \(7\) meters as the base. The altitude of length \(h\) that is perpendicular to this side is shown.

- Use right triangle trigonometry to determine the value of \(h\).

- Determine the area of this triangle.

- Answer

-

Using the right triangle, we see that \(\sin(26.5^\circ) = \dfrac{h}{5}\). So \(h = 5\sin(26.5^\circ)\), and the area of the triangle is

\[A = \dfrac{1}{2}(7)[5\sin(26.5^\circ)] = \dfrac{35}{2}\sin(26.5^\circ) \approx 7.8085\]

The area of the triangle is approximately \(7.8085\) square meters.

The purpose of Progress Check 3.21 was to illustrate that if we know the length of two sides of a triangle and the angle formed by these two sides, then we can determine the area of that triangle.

The Area of a Triangle

The area of a triangle equals one-half the product of two of its sides times the sine of the angle formed by these two sides.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

In the diagram on the right, \(b\) is the length of the base of a triangle, \(a\) is the length of another side, and \(\theta\) is the angle formed by these two sides. We let \(A\) be the area of the triangle.

Follow the procedure illustrated in Progress Check 3.21 to prove that \[A = \dfrac{1}{2}ab\sin(\theta)\]

Explain why this proves the formula for the area of a triangle.

- Answer

-

Using the right triangle, we see that \(\sin(\theta) = \dfrac{h}{a}\). So \(h = a\sin(\theta\), and the area of the triangle is \[A = \dfrac{1}{2}b(a\sin(\theta)) = \dfrac{1}{2}ab\sin(\theta)\]

There is another common formula for the area of a triangle known as Heron’s Formula named after Heron of Alexandria (circa 75 CE). This formula shows that the area of a triangle can be computed if the lengths of the three sides of the triangle are known.

Heron’s Formula

The area \(A\) of a triangle with sides of length \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\) is given by the formula

\[A = \sqrt{s(s - a)(s - b)(s - c)} \label{Heron}\]

where \(s = \dfrac{1}{2}(a+ b + c)\).

For example, suppose that the lengths of the three sides of a triangle are \(a = 3ft\), \(b = 5ft\), and \(c = 6ft\). Using Heron’s Formula (Equation \ref{Heron}), we get

\[s = \dfrac{1}{2}(a+ b + c)\]

\[s = 7\]

\[A = \sqrt{s(s - a)(s - b)(s - c)}\]

\[A = \sqrt{7(7 - 3)(7 - 5)(7 - 6)}\]

\[A = \sqrt{42}\]

This fairly complex formula is actually derived from the previous formula for the area of a triangle and the Law of Cosines. We begin our exploration of the proof of this formula in Progress Check

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

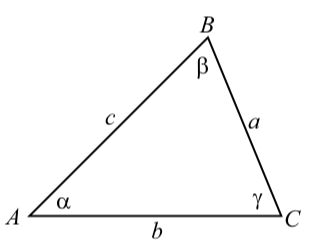

Suppose we have a triangle as shown in the diagram below.

- Use the Law of Cosines that involves the angle \(\gamma\) and solve this formula for \(\cos(\gamma)\). This gives a formula for \(\cos(\gamma)\) in terms of \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\).

- Use the Pythagorean Identity \(\cos^{2}(\gamma) + \sin^{2}(\gamma) = 1\)1 to write \(\sin(\gamma)\) in terms of \(\cos^{2}(\gamma)\). Substitute for \(\cos^{2}(\gamma)\) using the formula in (1). This gives a formula for \(\sin(\gamma)\) in terms of \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\). (Do not do any algebraic simplification.)

- We also know that a formula for the area of this triangle is \(A = \dfrac{1}{2}ab\sin(\gamma)\)

Substitute for \(\sin(\gamma)\) using the formula in (2). (Do not do any algebraic simplification.) This gives a formula for the area \(A\) in terms of \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\).

The formula obtained in Progress Check 3.23 was \[A = \dfrac{1}{2}ab\sqrt{1 - (\dfrac{a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2}}{2ab})^{2}}\]

This is a formula for the area of a triangle in terms of the lengths of the three sides of the triangle. It does not look like Heron’s Formula, but we can use some substantial algebra to rewrite this formula to obtain Heron’s Formula. This algebraic work is completed in the appendix for this section.

- Answer

-

1. Using the Law of Cosines, we see that \[c^{2} = a^{2} + b^{2} - 2ab\cos(\gamma)\] \[2ab\cos(\gamma) = a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2}\] \[\cos(\gamma) = \dfrac{a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2}}{2ab}\]

2. We see that

\[\sin^{2}(\gamma) = 1 - \cos^{2}(\gamma).\]

Since \(\gamma\) is between \(0^\circ\) and \(180^\circ\), we know that \(\sin(\gamma) > 0\) and so

\[\sin(\gamma) = \sqrt{\dfrac{a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2}{2ab}}\]

3. Substituting the equation in part (2) into the formula \(A = \dfrac{1}{ab}\sin(\gamma)\), we obtain

\[A = \dfrac{1}{2}ab\sin(\gamma) = \dfrac{1}{2}ab\sqrt{1 - (\dfrac{a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2}{2ab})^{2}}\]

Appendix – Proof of Heron’s Formula

The formula for the area of a triangle obtained in Progress Check 3.23 was \[A = \dfrac{1}{2}ab\sqrt{1 - (\dfrac{a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2}}{2ab})^{2}}\]

We now complete the algebra to show that this is equivalent to Heron’s formula. The first step is to rewrite the part under the square root sign as a single fraction.

\[A = \dfrac{1}{2}ab\sqrt{1 - (\dfrac{a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2}}{2ab})^{2}}\]

\[= \dfrac{1}{2}ab\sqrt{\dfrac{(2ab)^{2} - (a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2})^{2}}{(2ab)^{2}}}\]

\[= \dfrac{1}{2}ab\dfrac{\sqrt{(2ab)^{2} - (a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2})^{2}}}{2ab}\]

\[= \dfrac{\sqrt{(2ab)^{2} - (a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2})^{2}}}{4}\]

Squaring both sides of the last equation, we obtain \[A^{2} = \dfrac{(2ab)^{2} - (a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2})^{2}}{16}\]

The numerator on the right side of the last equation is a difference of squares. We will now use the difference of squares formula, \(x^{2} - y^{2} = (x - y)(x + y)\) to factor the numerator.

\[A^{2} = \dfrac{(2ab)^{2} - (a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2})^{2}}{16}\]

\[= \dfrac{(2ab - (a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2}))(2ab + (a^{2} + b^{2} - c^{2}))}{16}\]

\[= \dfrac{(-a^{2} + 2ab - b^{2} + c^{2})(a^{2} + 2ab + b^{2} - c^{2})}{16}\]

We now notice that \(-a^{2} + 2ab - b^{2} = -(a - b)^{2}\) and \(a^{2} + 2ab + b^{2} = (a + b)^{2}\). So using these in the last equation, we have

\[A^{2} = \dfrac{(-(a - b)^{2} + c^{2})((a + b)^{2} - c^{2})}{16}\]

\[= \dfrac{(-[(a - b)^{2} - c^{2}])((a + b)^{2} - c^{2})}{16}\]

We can once again use the difference of squares formula as follows:

\[(a - b)^{2} - c^{2} = (a - b - c)(a - b + c)\]

\[(a + b)^{2} - c^{2} = (a + b - c)(a + b + c)\]

Substituting this information into the last equation for \(A^{2}\), we obtain \[A^{2} = \dfrac{-(a - b - c)(a - b + c)(a + b - c)(a + b + c)}{16}\]

Since \(s = \dfrac{1}{2}(a + b + c)\), \(2s = a + b + c\) Now notice that

\[-(a - b - c) = -a + b + c = a + b + c - 2a = 2s - 2a\]

\[a - b + c = a + b + c -2b = 2s - 2b\]

\[a + b + c = a + b + c -2c = 2s - 2c\]

\[a + b + c = 2s\]

so

\[A^{2} = \dfrac{-(a - b - c)(a - b + c)(a + b - c)(a + b + c)}{16}\]

\[= \dfrac{(2s - 2a)(2s - 2b)(2s - 2c)(2s)}{16}\]

\[= \dfrac{16s(s - a)(s - b)(s - c)}{16}\]

\[= s(s - a)(s - b)(s - c)\]

\[A = \sqrt{s(s - a)(s - b)(s - c)}\]

This completes the proof of Heron’s formula.

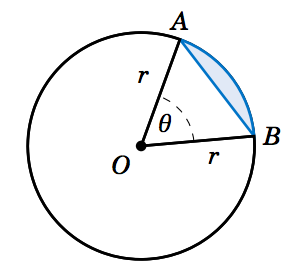

Area of a Sector & Area of a Segment

In geometry you learned that the area of a circle of radius \(r \) is \(\pi r^2 \). We will now learn how to find the area of a sector of a circle. A sector is the region bounded by a central angle and its intercepted arc.

Let \(\theta \) be a central angle in a circle of radius \(r \) and let \(A \) be the area of its sector. Similar to arc length, the ratio of \(A \) to the area of the entire circle is the same as the ratio of \(\theta \) to one revolution. In other words, again using radian measure,

\[\nonumber

\frac{\text{area of sector}}{\text{area of entire circle}} ~=~

\frac{\text{sector angle}}{\text{one revolution}} \quad\Rightarrow\quad

\frac{A}{\pi\,r^2} ~=~ \frac{\theta}{2\pi} ~.

\]

Solving for \(A \) in the above equation, we get a formula.

Definition: Area of a Sector

In a circle of radius \(r \), the area \(A \) of the sector inside a central angle \(\theta \) is

\[ A ~=~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,r^2 \;\theta ~,\label{eqn:sectorarea}\]

where \(\theta \) is measured in radians.

Applying the Equation

Using \(\theta=\frac{\pi}{5} \) and \(r=4 \) in Equation \ref{eqn:sectorarea}, the area \(A \) of the sector is

\[\nonumber

A ~=~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,r^2 \;\theta ~= \tfrac{1}{2}\,(4)^2 \;\cdot\;\tfrac{\pi}{5}

~=~ \boxed{\tfrac{8\pi}{5}~\text{cm}^2} ~.

\]

Example 8.3.1

Find the area of a sector whose angle is \(117^\circ \) in a circle of radius \(3.5 \) m.

Solution:

As with arc length, we have to make sure that the angle is measured in radians or else the answer will be way off. So converting \(\theta=117^\circ \) to radians and using \(r=3.5 \) in Equation \ref{eqn:sectorarea} for the area \(A \) of the sector, we get

\[\nonumber

\theta ~=~ 117^\circ ~=~ \frac{\pi}{180} \;\cdot\; 117 ~=~ 2.042~\text{rad}

\quad\Rightarrow\quad

A ~=~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,r^2 \;\theta ~= \tfrac{1}{2}\,(3.5)^2 \;(2.042)

~=~{12.51~\text{m}^2} ~.

\]

For a sector whose angle is \(\theta \) in a circle of radius \(r \), the length of the arc cut off by that angle is \(s=r\,\theta \). Thus, by Equation \ref{eqn:sectorarea} the area \(A \) of the sector can be written as:

\[

{ A ~=~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,rs}\label{eqn:sectorarc}

\]

Note: The central angle \(\theta \) that intercepts an arc is sometimes called the angle subtended by the arc.

Example 8.3.2

Using \(s=6 \) and \(r=9 \) in Equation \ref{eqn:sectorarc} for the area \(A \), we get

\[\nonumber

A ~=~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,rs ~=~ ~=~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,(9)\,(6) ~=~ \boxed{27~\text{cm}^2} ~.

\]

Note that the angle subtended by the arc is \(\theta = \frac{s}{r} = \frac{2}{3} \) rad.

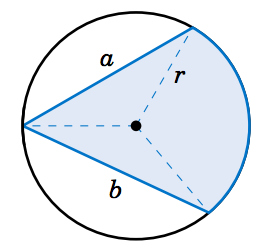

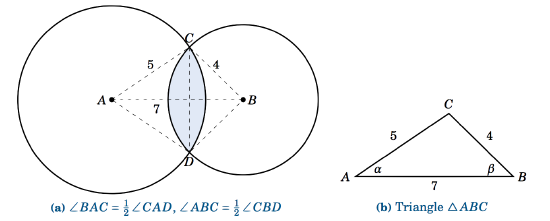

So far we have dealt with the area cut off by a central angle. How would you find the area of a region cut off by an inscribed angle, such as the shaded region in Figure 8.3.1? In this picture, the center of the circle is inside the inscribed angle, and the lengths \(a \) and \(b\) of the two chords are given, as is the radius \(r \) of the circle. Drawing line segments from the center of the circle to the endpoints of the chords indicates how to solve this problem: add up the areas of the two triangles and the sector formed by the central angle. The areas and angles of the two triangles can be determined (since all three sides are known) using methods from pervious sections. Also, note that a central angle has twice the measure of any inscribed angle which intercepts the same arc. In the exercises you will be asked to solve problems like this (including the cases where the center of the circle is outside or on the inscribed angle).

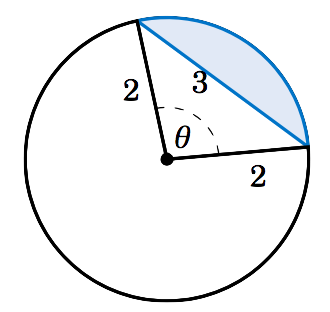

Another type of region we can consider is a segment of a circle, which is the region between a chord and the arc it cuts off. In Figure 8.3.2 the segment formed by the chord \(\overline{AB} \) is the shaded region between the arc \(\overparen{AB} \) and the triangle \(\triangle\,OAB \). For the area of a triangle given two sides and their included angle, we know that

\[\nonumber

\text{area of } \triangle\,OAB ~=~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,(r)\,(r)\,\sin\;\theta ~=~

\tfrac{1}{2}\,r^2 \,\sin\;\theta ~.

\]

Thus, since the area \(K \) of the segment is the area of the sector \(AOB \) minus the area of the triangle \(\triangle\,OAB \), we have

\[

\text{area \(K \) of segment } AB ~=~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,r^2 \;\theta ~-~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,r^2 \,\sin\;\theta

~=~{\tfrac{1}{2}\,r^2 \,(\theta - \sin\;\theta)} ~.\label{eqn:segment}

\]

Note that as a consequence of Equation \ref{eqn:segment} we must have \(\;\theta > \sin\;\theta\) for \(0 < \theta \le \pi \) (measured in radians), since the area of a segment is positive for those angles. See Figure 8.3.2.

Example 8.3.3

Given Figure 8.3.3, with radius 2 and chord 3, find the segment.

Solution

Figure 8.3.3 shows the segment formed by a chord of length \(3 \) in a circle of radius \(r=2 \). We can use the Law of Cosines to find the subtended central angle \(\theta\):

\[\nonumber

\cos\;\theta ~=~ \frac{2^2 + 2^2 - 3^2}{2\,(2)\,(2)} ~=~ -0.125 \quad\Rightarrow\quad

\theta ~=~ 1.696~\text{rad}

\]

Thus, by Equation \ref{eqn:segment} the area \(K \) of the segment is:

\[\nonumber

K ~=~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,r^2 \,(\theta - \sin\;\theta) ~=~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,(2)^2 \,

(1.696 - \sin\;1.696) ~=~ \boxed{1.408}

\]

Example 8.3.4

The centers of two circles are \(7 \) cm apart, with one circle having a radius of \(5 \) cm and the other a radius of \(4 \) cm. Find the area \(K \) of their intersection.

Solution:

By symmetry, we see that \(\angle\,BAC = \frac{1}{2}\,\angle\,CAD \) and \(\angle\,ABC = \frac{1}{2}\,\angle\,CBD \). So let \(\alpha = \angle\,BAC \) and \(\beta = \angle\,ABC \), as in Figure 4.3.6(b). By the Law of Cosines, we have

\[ \begin{alignat*}{7}

\cos\;\alpha ~&=~ \frac{7^2 + 5^2 - 4^2}{2\,(7)\,(5)} ~&=~ 0.8286 \quad&\Rightarrow\quad

\alpha ~&=~ 0.594~\text{rad} \quad&\Rightarrow\quad \angle\,CAD ~&=~2\,(0.594) = 1.188~\text{rad}\\ \nonumber

\cos\;\beta ~&=~ \frac{7^2 + 4^2 - 5^2}{2\,(7)\,(4)} ~&=~ 0.7143 \quad&\Rightarrow\quad

\beta ~&=~ 0.775~\text{rad} \quad&\Rightarrow\quad \angle\,CBD ~&=~ 2\,(0.775) = 1.550~\text{rad}

\end{alignat*}\]

Thus, the area \(K \) is

\[\nonumber \begin{align*}

K ~&=~ (\text{Area of segment \(CD \) in circle at \(A\)}) ~+~

(\text{Area of segment \(CD \) in circle at \(B\)})\\ \nonumber

&=~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,(5)^2 \,(1.188 - \sin\;1.188) ~+~ \tfrac{1}{2}\,(4)^2 \,(1.550 - \sin\;1.550)\\ \nonumber

&=~ \boxed{7.656~\text{cm}^2} ~.

\end{align*}\]

Contributors and Attributions

Michael Corral (Schoolcraft College). The content of this page is distributed under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

Summary

In this section, we studied the following important concepts and ideas:

- How to use right triangle trigonometry, the Law of Sines, and the Law of Cosines to solve applied problems involving triangles.

- Three ways to determine the area \(A\) of a triangle.

- How to find the area of a sector and some additional creative ways to calculate areas of overlap between two circles and segments.

\(A = \dfrac{1}{2}bh\), where \(b\) is the length of the base and \(h\) is the length of the altitude.

\(A = \dfrac{1}{2}ab\), where \(a\) and \(b\) are the lengths of two sides of the triangle and \(\theta\) is the angle formed by the sides of length \(a\) and \(b\).

Heron’s Formula. If \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\) are the lengths of the sides of a triangle and \(s = \dfrac{1}{2}(a + b + c)\), then \[A = \sqrt{s(s - a)(s - b)(s - c)}.\]