3.2: Graphing Linear Equations

- Page ID

- 104817

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Graph a linear equation by plotting points

- Graph vertical and horizontal lines

- Find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts

- Graph a line using the intercepts

- Evaluate \(5x - 4\) when \(x = -1\).

- Evaluate \(3x - 2y\) when \(x = 4, y = -3\).

- Solve for \(y: 8 - 3y = 20\).

- Answer

-

- -9

- 18

- \(y = -4\)

Linear Equations with Two Variables

Up to now, all the equations you have solved were equations with just one variable. In almost every case, when you solved the equation you got exactly one solution. But equations can have more than one variable. Equations with two variables may be of the form \(Ax+By=C\). An equation of this form is called a linear equation in two variables.

An equation of the form \(Ax+By=C\), where \(A\) and \(B\) are not both zero, is called a linear equation in two variables.

Here is an example of a linear equation in two variables, \(x\) and \(y\).

\(\begin{align*} {\color{BrickRed}A}x + {\color{RoyalBlue}B}y &= {\color{forestgreen}C} \\[5pt]

x+{\color{RoyalBlue}4}y &= {\color{forestgreen}8} \end{align*}\)

\({\color{BrickRed}A = 1}\), \({\color{RoyalBlue}B = 4}\), \({\color{forestgreen}C=8}\)

The equation \(y=−3x+5\) is also a linear equation. But it does not appear to be in the form \(Ax+By=C\). We can use the Addition Property of Equality and rewrite it in \(Ax+By=C\) form.

\[ \begin{array} {lrll} {} &{y} &= &{-3x+5} \\ {\text{Add to both sides.} } &{y+3x} &= &{3x+5+3x} \\ {\text{Simplify.} } &{y+3x} &= &{5} \\ {\text{Use the Commutative Property to put it in} } &{} &{} &{} \\ {Ax+By=C\text{ form.} } &{3x+y} &= &{5} \end{array} \nonumber\]

By rewriting \(y=−3x+5\) as \(3x+y=5\), we can easily see that it is a linear equation in two variables because it is of the form \(Ax+By=C\). When an equation is in the form \(Ax+By=C\), we say it is in standard form of a linear equation.

A linear equation is in standard form when it is written \(Ax+By=C\).

Most people prefer to have \(A,\) \(B,\) and \(C\) be integers and \(A \geq 0\) when writing a linear equation in standard form, although it is not strictly necessary.

Linear equations have infinitely many solutions. For every number that is substituted for \(x\) there is a corresponding \(y\)-value. This pair of values is a solution to the linear equation and is represented by the ordered pair \((x,y)\). When we substitute these values of \(x\) and \(y\) into the equation, the result is a true statement, because the value on the left side is equal to the value on the right side.

An ordered pair \((x,y)\) is a solution of the linear equation \(Ax+By=C\), if the equation is a true statement when the \(x\)- and \(y\)-values of the ordered pair are substituted into the equation.

Graphs of Solutions to Linear Equations

Now, in our last chapter, we learned how to graph ordered pairs. We can do the same thing here with the solutions to linear equations. Linear equations have infinitely many solutions. We can plot these solutions in the rectangular coordinate system. The points will line up perfectly in a straight line. We connect the points with a straight line to get the graph of the equation. We put arrows on the ends of each side of the line to indicate that the line continues in both directions.

A graph is a visual representation of all the solutions of the equation. It is an example of the saying, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” The line shows you all the solutions to that equation. Every point on the line is a solution of the equation. And, every solution of this equation is on this line. This line is called the graph of the equation. Points not on the line are not solutions!

The graph of a linear equation \(Ax+By=C\) is a straight line.

- Every point on the line is a solution of the equation.

- Every solution of this equation is a point on this line.

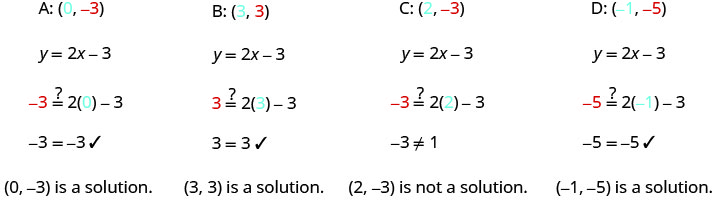

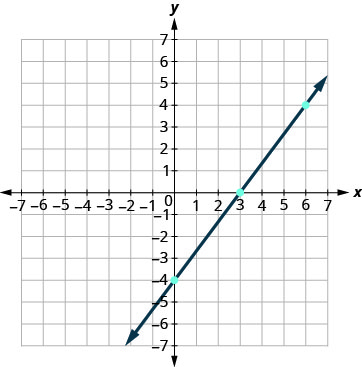

The graph of \(y=2x−3\) is shown.

For each ordered pair, decide:

- Is the ordered pair a solution to the equation?

- Is the point on the line?

A: \((0,−3)\) B: \((3,3)\) C: \((2,−3)\) D: \((−1,−5)\)

Solution

Substitute the \(x\)- and \(y\)-values into the equation to check if the ordered pair is a solution to the equation.

a.

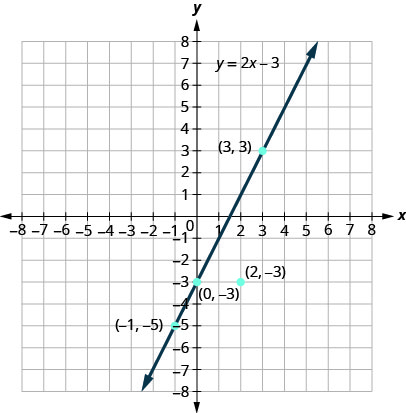

b. Plot the points \((0,−3)\), \((3,3)\), \((2,−3)\), and \((−1,−5)\).

The points \((0,3)\), \((3,−3)\), and \((−1,−5)\) are on the line \(y=2x−3\), and the point \((2,−3)\) is not on the line.

The points that are solutions to \(y=2x−3\) are on the line, but the point that is not a solution is not on the line.

Use graph of \(y=3x−1\). For each ordered pair, decide:

a. Is the ordered pair a solution to the equation?

b. Is the point on the line?

A \((0,−1)\) B \((2,5)\)

- Answer

-

a. yes b. yes

Use graph of \(y=3x−1\). For each ordered pair, decide:

a. Is the ordered pair a solution to the equation?

b. Is the point on the line?

A\((3,−1)\) B\((−1,−4)\)

- Answer

-

a. no b. yes

Graph a Linear Equation by Plotting Points

There are several methods that can be used to graph a linear equation. The first method we will use is called plotting points, or the Point-Plotting Method, which is the same tool we used in the last chapter. We find some points whose coordinates are solutions to the equation and then plot them in a rectangular coordinate system. By connecting these points in a line, we have the graph of the linear equation.

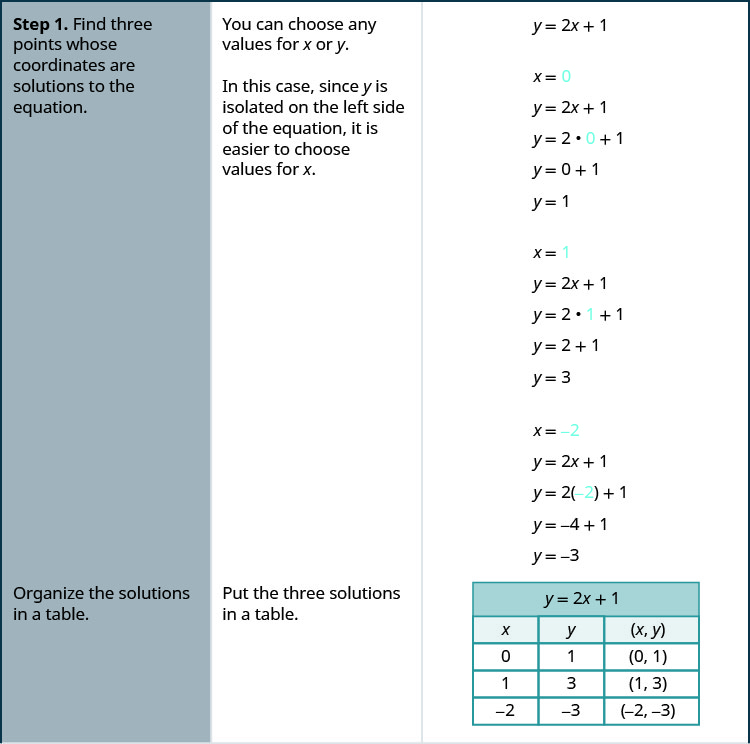

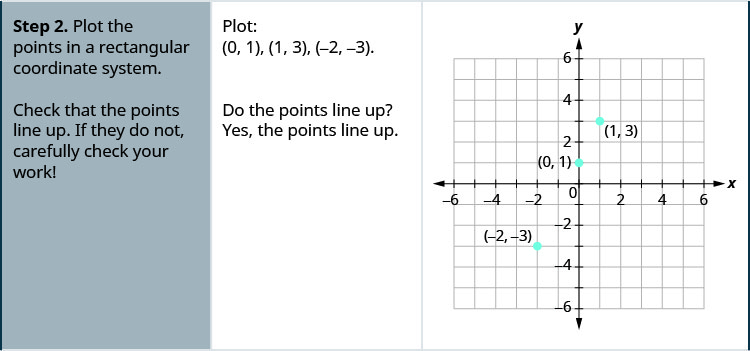

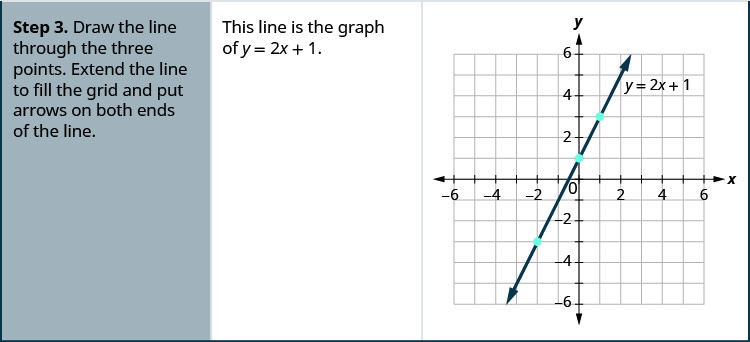

Graph the equation \(y=2x+1\) by plotting points.

Solution

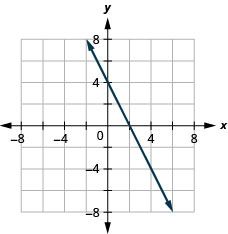

Graph the equation by plotting points: \(y=2x−3\).

- Answer

-

Graph the equation by plotting points: \(y=−2x+4\).

- Answer

-

The steps to take when graphing a linear equation by plotting points are summarized here.

- Find three points whose coordinates are solutions to the equation. Organize them in a table.

- Plot the points in a rectangular coordinate system. Check that the points line up. If they do not, carefully check your work.

- Draw the line through the three points. Extend the line to fill the grid and put arrows on both ends of the line.

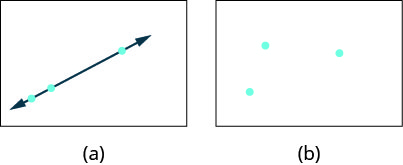

It is true that it only takes two points to determine a line, but it is a good habit to use three points. If you only plot two points and one of them is incorrect, you can still draw a line but it will not represent the solutions to the equation. It will be the wrong line.

If you use three points, and one is incorrect, the points will not line up. This tells you something is wrong and you need to check your work. Look at the difference between these illustrations.

When an equation includes a fraction as the coefficient of \(x,\) we can still substitute any numbers for \(x.\) But the arithmetic is easier if we make “good” choices for the values of \(x.\) This way we will avoid fractional answers, which are hard to graph precisely.

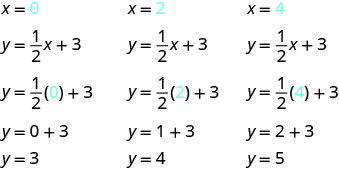

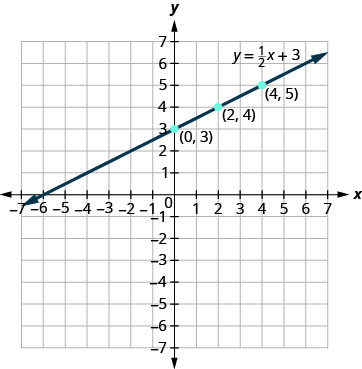

Graph the equation: \(y=\frac{1}{2}x+3\).

Solution

Find three points that are solutions to the equation. Since this equation has the fraction \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) as a coefficient of \(x,\) we will choose values of \(x\) carefully. We will use zero as one choice and multiples of \(2\) for the other choices. Why are multiples of two a good choice for values of \(x\)? By choosing multiples of \(2\) the multiplication by \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) simplifies to a whole number

The points are shown in Table.

| \(y=\frac{1}{2}x+3\) | ||

| \(x\) | \(y\) | \((x,y)\) |

| 0 | 3 | \((0,3)\) |

| 2 | 4 | \((2,4)\) |

| 4 | 5 | \((4,5)\) |

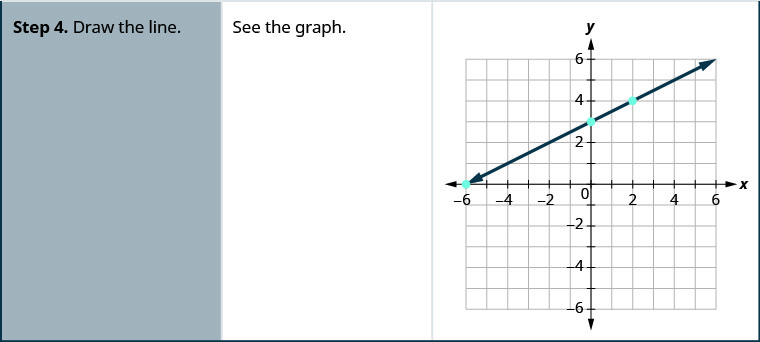

Plot the points, check that they line up, and draw the line.

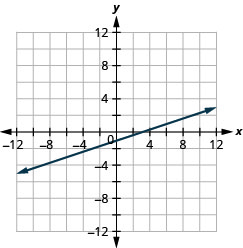

Graph the equation: \(y=\frac{1}{3}x−1\).

- Answer

-

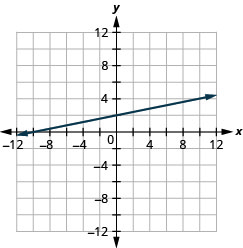

Graph the equation: \(y=\frac{1}{4}x+2\).

- Answer

-

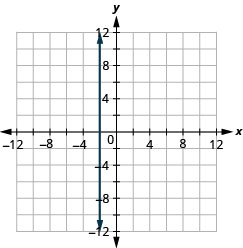

Graph Vertical and Horizontal Lines

Some linear equations have only one variable. They may have just \(x\) and no \(y,\) or just \(y\) without an \(x.\) This changes how we make a table of values to get the points to plot.

Let’s consider the equation \(x=−3\). This equation has only one variable, \(x.\) The equation says that \(x\)is always equal to \(−3\), so its value does not depend on \(y.\) No matter what is the value of \(y,\) the value of \(x\) is always \(−3\).

So to make a table of values, write \(−3\) in for all the \(x\)-values. Then choose any values for \(y.\) Since \(x\) does not depend on \(y,\) you can choose any numbers you like. But to fit the points on our coordinate graph, we’ll use 1, 2, and 3 for the \(y\)-coordinates. See Table.

| \(x=−3\) | ||

| \(x\) | \(y\) | \((x,y)\) |

| \(−3\) | 1 | \((−3,1)\) |

| \(−3\) | 2 | \((−3,2)\) |

| \((−3,)\) | 3 | \((−3,3)\) |

Plot the points from the table and connect them with a straight line. Notice that we have graphed a vertical line.

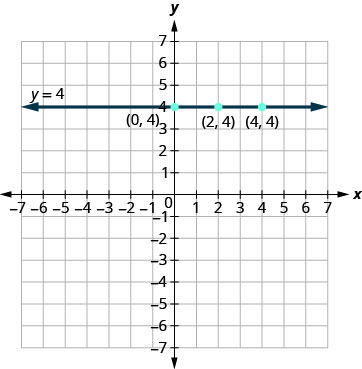

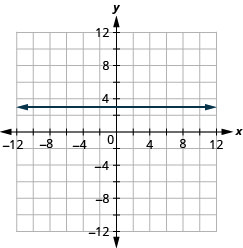

What if the equation has \(y\) but no \(x\)? Let’s graph the equation \(y=4\). This time the y-value is a constant, so in this equation, \(y\) does not depend on \(x.\) Fill in \(4\) for all the \(y\)’s in Table and then choose any values for \(x.\) We’ll use 0, 2, and 4 for the \(x\)-coordinates.

| \(y=4\) | ||

| \(x\) | \(y\) | \((x,y)\) |

| 0 | 4 | \((0,4)\) |

| 2 | 4 | \((2,4)\) |

| 4 | 4 | \((4,4)\) |

In this figure, we have graphed a horizontal line passing through the \(y\)-axis at \(4.\)

A vertical line is the graph of an equation of the form \(x=a\).

The line passes through the \(x\)-axis at \((a,0)\).

A horizontal line is the graph of an equation of the form \(y=b\).

The line passes through the \(y\)-axis at \((0,b)\).

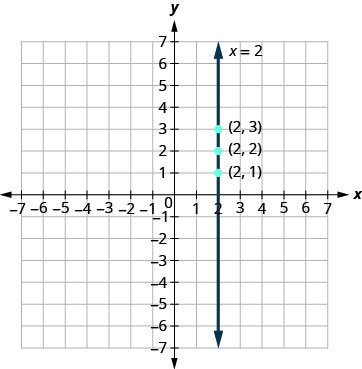

Graph: a. \(x=2\) b. \(y=−1\).

Solution

a. The equation has only one variable, \(x,\) and \(x\) is always equal to \(2.\) We create a table where \(x\) is always \(2\) and then put in any values for \(y.\) The graph is a vertical line passing through the \(x\)-axis at \(2.\)

| \(x\) | \(y\) | \((x,y)\) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | \((2,1)\) |

| 2 | 2 | \((2,2)\) |

| 2 | 3 | \((2,3)\) |

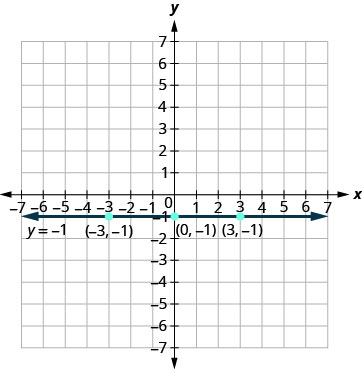

b. Similarly, the equation \(y=−1\) has only one variable, \(y\). The value of \(y\) is constant. All the ordered pairs in the next table have the same \(y\)-coordinate. The graph is a horizontal line passing through the \(y\)-axis at \(−1.\)

| \(\mathbf{x}\) | \(\mathbf{ y}\) | \(\mathbf{(x,y)}\) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | \(−1\) | \((0,−1)\) |

| 3 | \(−1\) | \((3,−1)\) |

| \(−3\) | \(−1\) | \((−3,−1)\) |

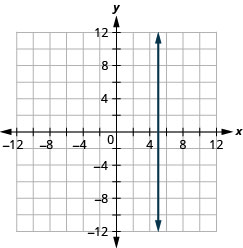

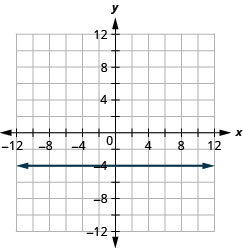

Graph the equations: a. \(x=5\) b. \(y=−4\).

- Answer

-

a.

b.

Graph the equations: a. \(x=−2\) b. \(y=3\).

- Answer

-

a.

b.

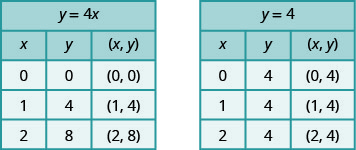

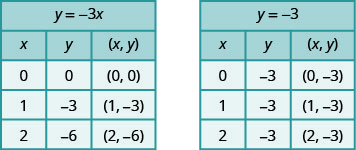

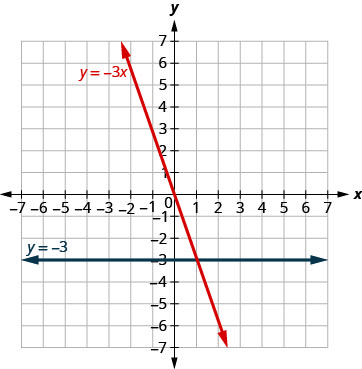

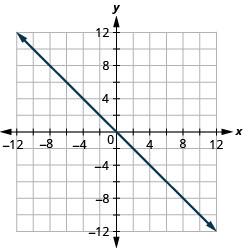

What is the difference between the equations \(y=4x\) and \(y=4\)?

The equation \(y=4x\) has both \(x\) and \(y.\) The value of \(y\) depends on the value of \(x,\) so the \(y\)-coordinate changes according to the value of \(x.\) The equation \(y=4\) has only one variable. The value of \(y\) is constant, it does not depend on the value of \(x,\) so the \(y\)-coordinate is always \(4.\)

Notice, in the graph, the equation \(y=4x\) gives a slanted line, while \(y=4\) gives a horizontal line.

Graph \(y=−3x\) and \(y=−3\) in the same rectangular coordinate system.

Solution

We notice that the first equation has the variable \(x,\) while the second does not. We make a table of points for each equation and then graph the lines. The two graphs are shown.

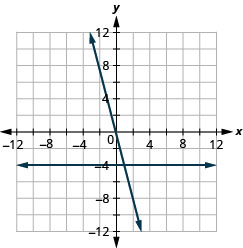

Graph the equations in the same rectangular coordinate system: \(y=−4x\) and \(y=−4\).

- Answer

-

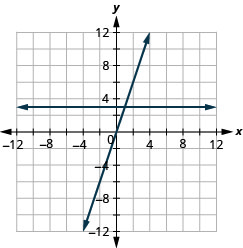

Graph the equations in the same rectangular coordinate system: \(y=3\)and \(y=3x\).

- Answer

-

Find \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts

Every linear equation can be represented by a unique line that shows all the solutions of the equation. We have seen that when graphing a line by plotting points, you can use any three solutions to graph. This means that two people graphing the line might use different sets of three points.

At first glance, their two lines might not appear to be the same, since they would have different points labeled. But if all the work was done correctly, the lines should be exactly the same. One way to recognize that they are indeed the same line is to look at where the line crosses the \(x\)-axis and the \(y\)-axis. These points are called the intercepts of a line.

The points where a line crosses the \(x\)-axis and the \(y\)-axis are called the intercepts of the line.

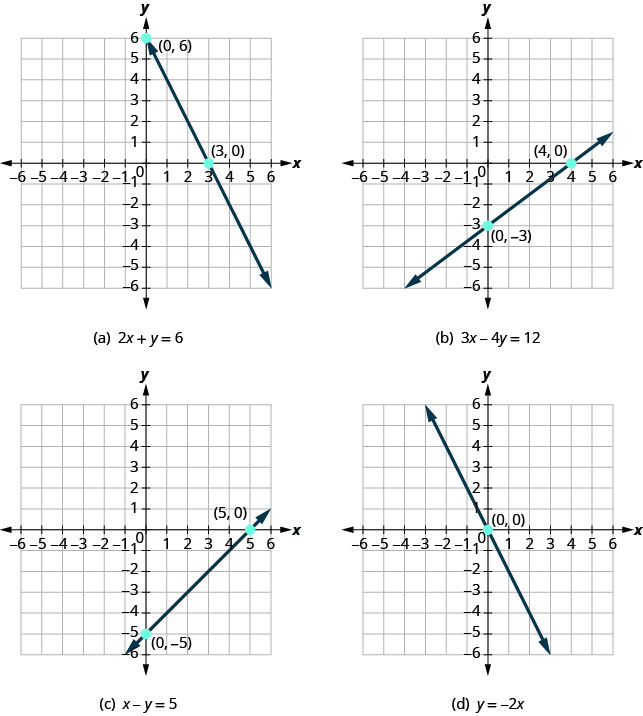

Let’s look at the graphs of the lines.

First, notice where each of these lines crosses the \(x\)-axis. See Table.

Now, let’s look at the points where these lines cross the \(y\)-axis.

| Figure | The line crosses the \(x\)-axis at: |

Ordered pair for this point |

The line crosses the y-axis at: |

Ordered pair for this point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure (a) | \(3\) | \((3,0)\) | \(6\) | \((0,6)\) |

| Figure (b) | \(4\) | \((4,0)\) | \(−3\) | \((0,−3)\) |

| Figure (c) | \(5\) | \((5,0)\) | \(−5\) | \((0,5)\) |

| Figure (d) | \(0\) | \((0,0)\) | \(0\) | \((0,0)\) |

| General Figure | \(a\) | \((a,0)\) | \(b\) | \((0,b)\) |

Do you see a pattern?

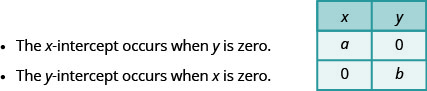

For each line, the \(y\)-coordinate of the point where the line crosses the \(x\)-axis is zero. The point where the line crosses the \(x\)-axis has the form \((a,0)\) and is called the \(x\)-intercept of the line. The \(x\)-intercept occurs when \(y\) is zero.

In each line, the \(x\)-coordinate of the point where the line crosses the \(y\)-axis is zero. The point where the line crosses the \(y\)-axis has the form \((0,b)\) and is called the \(y\)-intercept of the line. The \(y\)-intercept occurs when \(x\) is zero.

The \(x\)-intercept is the point \((a,0)\) where the line crosses the \(x\)-axis.

The \(y\)-intercept is the point \((0,b)\) where the line crosses the \(y\)-axis.

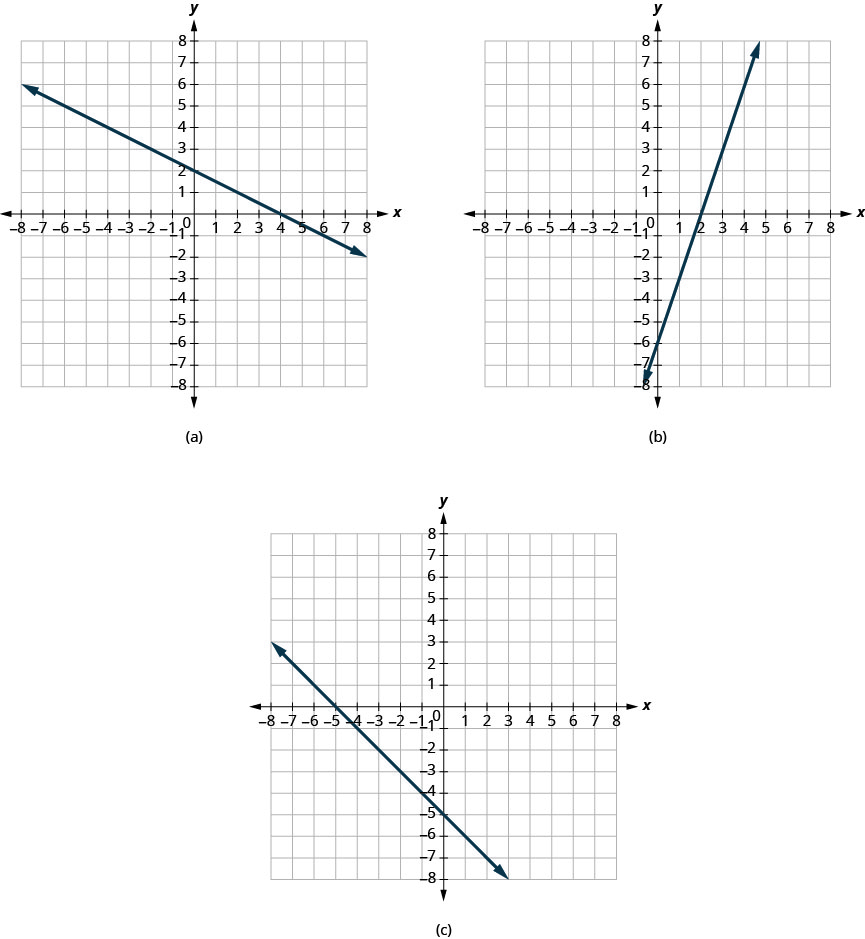

Find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts on each graph shown.

Solution

a. The graph crosses the \(x\)-axis at the point \((4,0)\). The x-intercept is \((4,0)\).

The graph crosses the \(y\)-axis at the point \((0,2)\). The \(y\)-intercept is \((0,2)\).

b. The graph crosses the \(x\)-axis at the point \((2,0)\). The \(x\)-intercept is \((2,0)\).

The graph crosses the \(y\)-axis at the point \((0,−6)\). The \(y\)-intercept is \((0,−6)\).

c. The graph crosses the \(x\)-axis at the point \((−5,0)\). The \(x\)-intercept is \((−5,0)\).

The graph crosses the \(y\)-axis at the point \((0,−5)\). The \(y\)-intercept is \((0,−5)\).

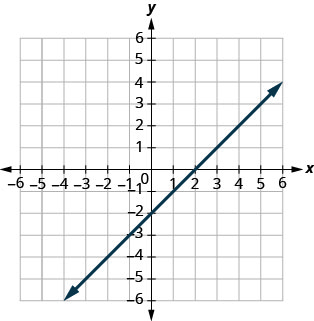

Find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts on the graph.

- Answer

-

\(x\)-intercept: \((2,0)\),

\(y\)-intercept: \((0,−2)\)

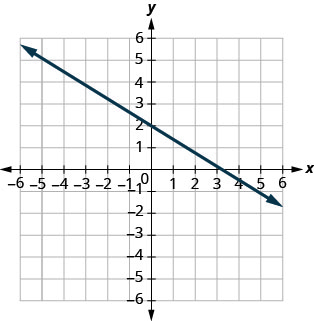

Find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts on the graph.

- Answer

-

\(x\)-intercept: \((3,0)\),

\(y\)-intercept: \((0,2)\)

Recognizing that the \(x\)-intercept occurs when \(y\) is zero and that the \(y\)-intercept occurs when \(x\) is zero, gives us a method to find the intercepts of a line from its equation. To find the \(x\)-intercept, let \(y=0\) and solve for \(x.\) To find the \(y\)-intercept, let \(x=0\) and solve for \(y.\)

Use the equation of the line. To find:

- the \(x\)-intercept of the line, let \(y=0\) and solve for \(x\).

- the \(y\)-intercept of the line, let \(x=0\) and solve for \(y\).

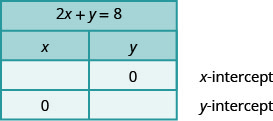

Find the intercepts of \(2x+y=8\).

Solution

We will let \(y=0\) to find the \(x\)-intercept, and let \(x=0\) to find the \(y\)-intercept. We will fill in a table, which reminds us of what we need to find.

| To find the \(x\)-intercept, let \(y=0\). | |

| \(2x+y=8\) | |

| Let \(y=0\). | \(2x+{\color{red}0}=8\) |

| Simplify. | \(2x=8\) |

| \(x=4\) | |

| The \(x\)-intercept is: | \((4,0)\) |

| To find the \(y\)-intercept, let \(x=0\). | |

| \(2x+y=8\) | |

| Let \(x=0\). | \(2 ( {\color{red}0}) + y = 8\) |

| Simplify. | \(0 + y = 8\) |

| \(y=8\) | |

| The \(y\)-intercept is: | \((0,8)\) |

The intercepts are the points \((4,0)\) and \((0,8)\) as shown in the table.

| \(2x+y=8\) | |

| \(x\) | \(y\) |

| 4 | 0 |

| 0 | 8 |

Find the intercepts: \(3x+y=12\).

- Answer

-

\(x\)-intercept: \((4,0)\),

\(y\)-intercept: \((0,12)\)

Find the intercepts: \(x+4y=8\).

- Answer

-

\(x\)-intercept: \((8,0)\),

\(y\)-intercept: \((0,2)\)

Graph a Line Using the Intercepts

To graph a linear equation by plotting points, you need to find three points whose coordinates are solutions to the equation. You can use the x- and y- intercepts as two of your three points. Find the intercepts, and then find a third point to ensure accuracy. Make sure the points line up—then draw the line. This method is often the quickest way to graph a line.

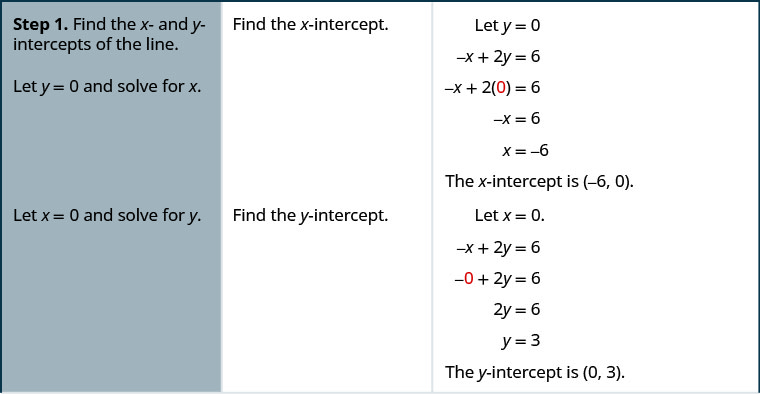

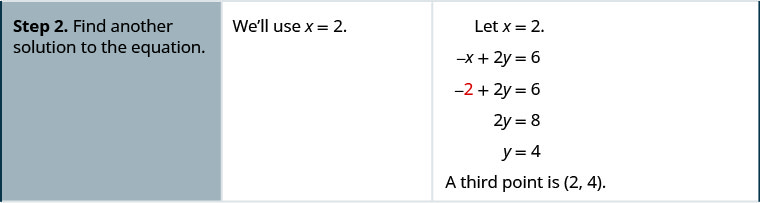

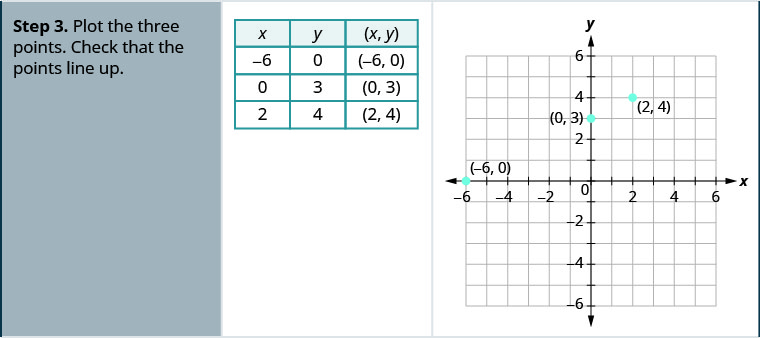

Graph \(–x+2y=6\) using the intercepts.

Solution

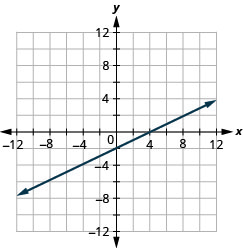

Graph using the intercepts: \(x–2y=4\).

- Answer

-

Graph using the intercepts: \(–x+3y=6\).

- Answer

-

The steps to graph a linear equation using the intercepts are summarized here.

- Find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts of the line.

- Let y=0y=0 and solve for \(x\).

- Let x=0x=0 and solve for \(y\).

- Find a third solution to the equation.

- Plot the three points and check that they line up.

- Draw the line.

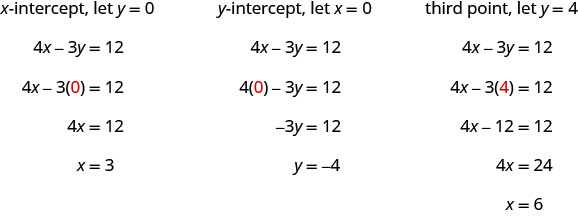

Graph \(4x−3y=12\) using the intercepts.

Solution

Find the intercepts and a third point.

We list the points in the table and show the graph.

| \(4x−3y=12\) | ||

| \(x\) | \(y\) | \((x,y)\) |

| 3 | 0 | \((3,0)\) |

| 0 | \(−4\) | \((0,−4)\) |

| 6 | 4 | \((6,4)\) |

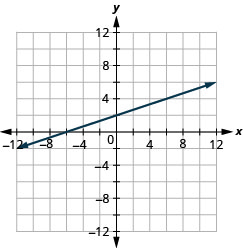

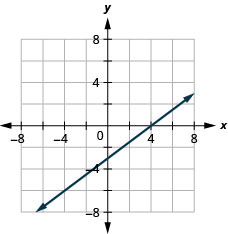

Graph using the intercepts: \(5x−2y=10\).

- Answer

-

Graph using the intercepts: \(3x−4y=12\).

- Answer

-

When the line passes through the origin, the \(x\)-intercept and the \(y\)-intercept are the same point.

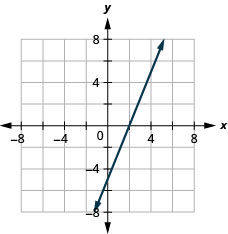

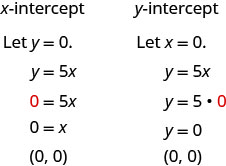

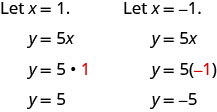

Graph \(y=5x\) using the intercepts.

Solution

This line has only one intercept. It is the point \((0,0)\).

To ensure accuracy, we need to plot three points. Since the \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts are the same point, we need two more points to graph the line.

The resulting three points are summarized in the table.

| \(y=5x\) | ||

| \(x\) | \(y\) | \((x,y)\) |

| 0 | 0 | \((0,0)\) |

| 1 | 5 | \((1,5)\) |

| \(−1\) | \(−5\) | \((−1,−5)\) |

Plot the three points, check that they line up, and draw the line.

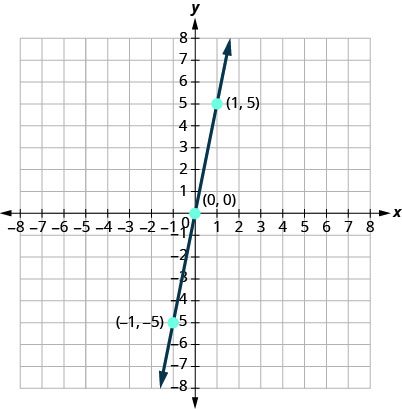

Graph using the intercepts: \(y=4x\).

- Answer

-

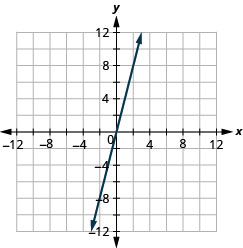

Graph the intercepts: \(y=−x\).

- Answer

-

Key Concepts

- Graph of a Linear Equation: The graph of a linear equation \(Ax+By=C\) is a straight line.

Every point on the line is a solution of the equation.

Every solution of this equation is a point on this line. - How to graph a linear equation by plotting points.

- Find three points whose coordinates are solutions to the equation. Organize them in a table.

- Plot the points in a rectangular coordinate system. Check that the points line up. If they do not, carefully check your work.

- Draw the line through the three points. Extend the line to fill the grid and put arrows on both ends of the line.

- \(x\)-intercept and \(y\)-intercept of a Line

- The \(x\)-intercept is the point \((a,0)\) where the line crosses the \(x\)-axis.

- The \(y\)-intercept is the point \((0,b)\) where the line crosses the \(y\)-axis.

- Find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts from the Equation of a Line

- Use the equation of the line. To find:

the \(x\)-intercept of the line, let \(y=0\) and solve for \(x.\)

the \(y\)-intercept of the line, let \(x=0\) and solve for \(y.\)

- Use the equation of the line. To find:

- How to graph a linear equation using the intercepts.

- Find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts of the line.

Let \(y=0\) and solve for \(x.\)

Let \(x=0\) and solve for \(y.\) - Find a third solution to the equation.

- Plot the three points and check that they line up.

- Draw the line.

- Find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts of the line.