2.3E: Exercises for Section 2.3

- Last updated

- Sep 6, 2022

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 112045

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

In exercises 1 - 4, use the limit laws to evaluate each limit. Justify each step by indicating the appropriate limit law(s).

1) limx→0(4x2−2x+3)

- Answer

-

Use constant multiple law and difference law:

limx→0(4x2−2x+3)=4limx→0x2−2limx→0x+limx→03=0+0+3=3

2) limx→1x3+3x2+54−7x

3) limx→−2√x2−6x+3

- Answer

- Use root law: limx→−2√x2−6x+3=√limx→−2(x2−6x+3)=√19

4) limx→−1(9x+1)2

In exercises 5 - 10, use direct substitution to evaluate the limit of each continuous function.

5) limx→7x2

- Answer

- limx→7x2=49

6) limx→−2(4x2−1)

7) limx→011+sinx

- Answer

- limx→011+sinx=1

8) limx→2e2x−x2

9) limx→12−7xx+6

- Answer

- limx→12−7xx+6=−57

10) limx→3lne3x

In exercises 11 - 20, use direct substitution to show that each limit leads to the indeterminate form 0/0. Then, evaluate the limit analytically.

11) limx→4x2−16x−4

- Answer

- When x=4,x2−16x−4=16−164−4=00;

then, limx→4x2−16x−4=limx→4(x+4)(x−4)x−4=limx→4(x+4)=4+4=8

12) limx→2x−2x2−2x

13) limx→63x−182x−12

- Answer

- When x=6,3x−182x−12=18−1812−12=00;

then, limx→63x−182x−12=limx→63(x−6)2(x−6)=limx→632=32

14) limh→0(1+h)2−1h

15) limt→9t−9√t−3

- Answer

- When t=9,t−9√t−3=9−93−3=00;

then, limt→9t−9√t−3=limt→9t−9√t−3√t+3√t+3=limt→9(t−9)(√t+3)t−9=limt→9(√t+3)=√9+3=6

16) limh→01a+h−1ah, where a is a real-valued constant

17) limθ→πsinθtanθ

- Answer

- When θ=π,sinθtanθ=sinπtanπ=00;

then, limθ→πsinθtanθ=limθ→πsinθsinθcosθ=limθ→πcosθ=cosπ=−1

18) limx→1x3−1x2−1

19) limx→1/22x2+3x−22x−1

- Answer

- When x=1/2,2x2+3x−22x−1=12+32−21−1=00;

then, limx→1/22x2+3x−22x−1=limx→1/2(2x−1)(x+2)2x−1=limx→1/2(x+2)=12+2=52

20) limx→−3√x+4−1x+3

In exercises 21 - 24, use direct substitution to obtain an undefined expression. Then, use the method used in Example 9 of this section to simplify the function and determine the limit.

21) limx→−2−2x2+7x−4x2+x−2

- Answer

- −∞

22) limx→−2+2x2+7x−4x2+x−2

23) limx→1−2x2+7x−4x2+x−2

- Answer

- −∞

24) limx→1+2x2+7x−4x2+x−2

In exercises 25 - 32, assume that limx→6f(x)=4,limx→6g(x)=9, and limx→6h(x)=6. Use these three facts and the limit laws to evaluate each limit.

25) limx→62f(x)g(x)

- Answer

- limx→62f(x)g(x)=2(limx→6f(x))(limx→6g(x))=2(4)(9)=72

26) limx→6g(x)−1f(x)

27) limx→6(f(x)+13g(x))

- Answer

- limx→6(f(x)+13g(x))=limx→6f(x)+13limx→6g(x)=4+13(9)=7

28) limx→6(h(x))32

29) limx→6√g(x)−f(x)

- Answer

- limx→6√g(x)−f(x)=√limx→6g(x)−limx→6f(x)=√9−4=√5

30) limx→6x⋅h(x)

31) limx→6[(x+1)⋅f(x)]

- Answer

- limx→6[(x+1)f(x)]=(limx→6(x+1))(limx→6f(x))=7(4)=28

32) limx→6(f(x)⋅g(x)−h(x))

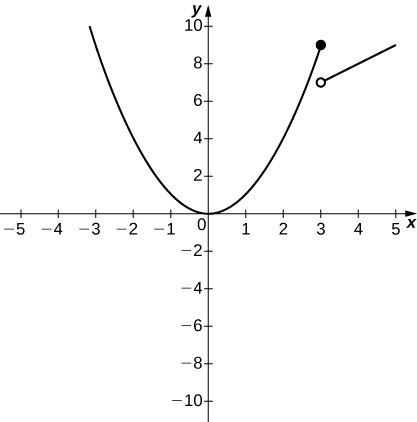

[T] In exercises 33 - 35, use a calculator to draw the graph of each piecewise-defined function and study the graph to evaluate the given limits.

33) f(x)={x2,x≤3x+4,x>3

a. limx→3−f(x)

b. limx→3+f(x)

- Answer

-

a. 9; b.7

34) g(x)={x3−1,x≤01,x>0

a. limx→0−g(x)

b. limx→0+g(x)

35) h(x)={x2−2x+1,x<23−x,x≥2

a. limx→2−h(x)

b. limx→2+h(x)

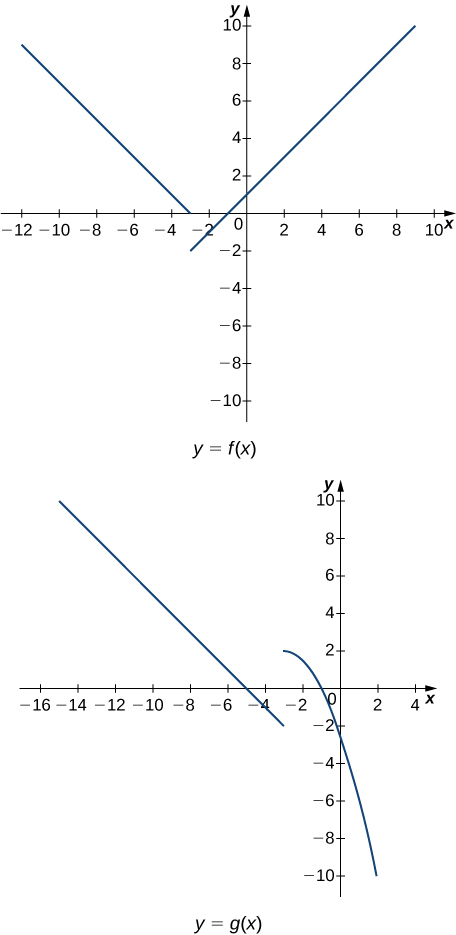

In exercises 36 - 43, use the following graphs and the limit laws to evaluate each limit.

36) limx→−3+(f(x)+g(x))

37) limx→−3−(f(x)−3g(x))

- Answer

- limx→−3−(f(x)−3g(x))=limx→−3−f(x)−3limx→−3−g(x)=0+6=6

38) limx→0f(x)g(x)3

39) limx→−52+g(x)f(x)

- Answer

- limx→−52+g(x)f(x)=2+(limx→−5g(x))limx→−5f(x)=2+02=1

40) limx→1(f(x))2

41) limx→13√f(x)−g(x)

- Answer

- limx→13√f(x)−g(x)=3√limx→1f(x)−limx→1g(x)=3√2+5=3√7

42) limx→−7(x⋅g(x))

43) limx→−9[x⋅f(x)+2⋅g(x)]

- Answer

- limx→−9(xf(x)+2g(x))=(limx→−9x)(limx→−9f(x))+2limx→−9g(x)=(−9)(6)+2(4)=−46

For exercises 44 - 46, evaluate the limit using the squeeze theorem. Use a calculator to graph the functions f(x), g(x), and h(x) when possible.

44) [T] True or False? If 2x−1≤g(x)≤x2−2x+3, then limx→2g(x)=0.

45) [T] limθ→0θ2cos(1θ)

- Answer

-

The limit is zero.

![The graph of three functions over the domain [-1,1], colored red, green, and blue as follows: red: theta^2, green: theta^2 * cos (1/theta), and blue: - (theta^2). The red and blue functions open upwards and downwards respectively as parabolas with vertices at the origin. The green function is trapped between the two.](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/1926/CNX_Calc_Figure_02_03_206.jpeg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=342&height=347)

46) limx→0f(x), where f(x)={0,x rationalx2,x irrrational

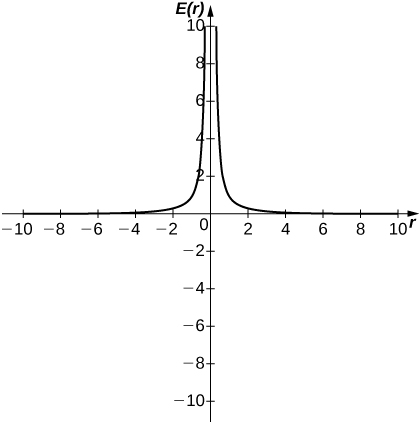

47) [T] In physics, the magnitude of an electric field generated by a point charge at a distance r in vacuum is governed by Coulomb’s law: E(r)=q4πε0r2, where E represents the magnitude of the electric field, q is the charge of the particle, r is the distance between the particle and where the strength of the field is measured, and 14πε0 is Coulomb’s constant: 8.988×109N⋅m2/C2.

a. Use a graphing calculator to graph E(r) given that the charge of the particle is q=10−10.

b. Evaluate limr→0+E(r). What is the physical meaning of this quantity? Is it physically relevant? Why are you evaluating from the right?

- Answer

-

a.

b. ∞. The magnitude of the electric field as you approach the particle q becomes infinite. It does not make physical sense to evaluate negative distance.

48) [T] The density of an object is given by its mass divided by its volume: ρ=m/V.

a. Use a calculator to plot the volume as a function of density (V=m/ρ), assuming you are examining something of mass 8 kg (m=8).

b. Evaluate limx→0+V(ρ) and explain the physical meaning.