5.2: Properties of Exponents and Scientific Notation

- Last updated

- Jan 7, 2020

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 30851

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Simplify expressions using the properties for exponents

- Use the definition of a negative exponent

- Use scientific notation

Simplify Expressions Using the Properties for Exponents

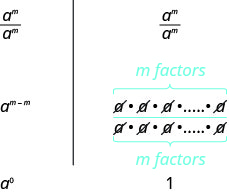

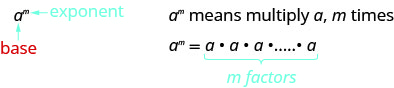

Remember that an exponent indicates repeated multiplication of the same quantity. For example, in the expression am, the exponent m tells us how many times we use the base a as a factor.

am=a⋅a⋅a⋅…⋅a⏟m factors

For example

(−9)5=(−9)⋅(−9)⋅(−9)⋅(−9)⋅(−9)⏟5 factors

Let’s review the vocabulary for expressions with exponents.

DEFINITION: EXPONENTIAL NOTATION

This is read a to the mth power.

In the expression am, the exponent m tells us how many times we use the base a as a factor.

When we combine like terms by adding and subtracting, we need to have the same base with the same exponent. But when you multiply and divide, the exponents may be different, and sometimes the bases may be different, too.

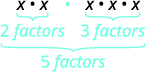

First, we will look at an example that leads to the Product Property.

|

x2⋅x3 |

||

| What does this mean? |

x⋅x⏟2factors⋅x⋅x⋅x⏟3factors |

|

| x5 |

Notice that 5 is the sum of the exponents, 2 and 3. We see x2⋅x3 is x2+3 or x5.

The base stayed the same and we added the exponents. This leads to the Product Property for Exponents.

DEFINITION: PRODUCT PROPERTY FOR EXPONENTS

If a is a real number and m and n are integers, then

am·an=am+n

To multiply with like bases, add the exponents.

Example 5.2.1

Simplify each expression:

- y5·y6

- 2x·23x

- 2a7·3a.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

Use the Product Property, am·an=am+n.

Simplify.

ⓑ

Use the Product Property, am·an=am+n.

Simplify.

ⓒ

Rewrite, a=a1.

Use the Commutative Property and

use the Product Property, am·an=am+n.

Simplify.

ⓓ

Add the exponents, since bases are the same.

Simplify.

Example 5.2.2

Simplify each expression:

- b9·b8

- 42x·4x

- 3p5·4p

- x6·x4·x8.

- Answer

-

ⓐ b17 ⓑ 43x ⓒ 12p6

ⓓ x18

Example 5.2.3

Simplify each expression:

- x12·x4

- 10·10x

- 2z·6z7

- b5·b9·b5.

- Answer a

-

x16

- Answer b

-

10x+1

- Answer c

-

12z8

- Answer d

-

b19

Now we will look at an exponent property for division. As before, we’ll try to discover a property by looking at some examples.

| Consider | x5x2 | and | x2x3 |

| What do they mean? | x·x·x·x·xx·x | x·xx·x·x | |

| Use the Equivalent Fractions Property. | x·x·x·x·xx·x | x·x·1x·x·x | |

| Simplify. | x3 |

1x |

Notice, in each case the bases were the same and we subtracted exponents. We see x5x2 is x5−2 or x3. We see x2x3 is or 1x. When the larger exponent was in the numerator, we were left with factors in the numerator. When the larger exponent was in the denominator, we were left with factors in the denominator--notice the numerator of 1. When all the factors in the numerator have been removed, remember this is really dividing the factors to one, and so we need a 1 in the numerator. xx=1. This leads to the Quotient Property for Exponents.

Definition: QUOTIENT PROPERTY FOR EXPONENTS

If a is a real number, a≠0, and m and n are integers, then

aman=am−n,m>nandaman=1an−m,n>m

Example 5.2.4

Simplify each expression:

- x9x7

- 31032

- b8b12

- 7375.

- Answer

-

To simplify an expression with a quotient, we need to first compare the exponents in the numerator and denominator.

ⓐ

Since 9>7, there are more factors of x in the numerator.

Use Quotient Property, aman=am−n.

Simplify.

ⓑ

Since 10>2, there are more factors of 3 in the numerator.

Use Quotient Property, aman=am−n.

Simplify.

Notice that when the larger exponent is in the numerator, we are left with factors in the numerator.

ⓒ

Since 12>8, there are more factors of bb in the denominator.

Use Quotient Property, aman=am−n.

Simplify.

ⓓ

Since 5>3, there are more factors of 3 in the denominator.

Use Quotient Property, aman=am−n.

Simplify.

Simplify.

Notice that when the larger exponent is in the denominator, we are left with factors in the denominator.

Example 5.2.5

Simplify each expression:

- x15x10

- 61465

- x18x22

- 12151230.

- Answer

-

ⓐ x5

ⓑ 69

ⓒ 1x4

ⓓ 11215

Example 5.2.6

Simplify each expression:

- y43y37

- 1015107

- m7m15

- 98919.

- Answer

-

ⓐ y6

ⓑ 108

ⓒ 1m8

ⓓ 1911

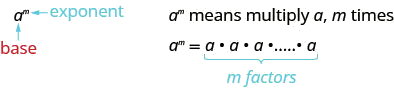

A special case of the Quotient Property is when the exponents of the numerator and denominator are equal, such as an expression like amam. We know, xx=1, for any x(x≠0) since any number divided by itself is 1.

The Quotient Property for Exponents shows us how to simplify amam. when m>n and when n<mn<m by subtracting exponents. What if m=n? We will simplify amam in two ways to lead us to the definition of the Zero Exponent Property. In general, for a≠0:

We see amam simplifies to a0 and to 1. So a0=1. Any non-zero base raised to the power of zero equals 1.

DEFINITION: ZERO EXPONENT PROPERTY

If a is a non-zero number, then a0=1.

If a is a non-zero number, then a to the power of zero equals 1.

Any non-zero number raised to the zero power is 1.

In this text, we assume any variable that we raise to the zero power is not zero.

ExAMPLE 5.2.7

Simplify each expression: ⓐ 90 ⓑ n0.

- Answer

-

The definition says any non-zero number raised to the zero power is 1.

ⓐ Use the definition of the zero exponent. 90=1

ⓑ Use the definition of the zero exponent. n0=1

To simplify the expression n raised to the zero power we just use the definition of the zero exponent. The result is 1.

Example 5.2.8

Simplify each expression: ⓐ 110 ⓑ q0.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 1

ⓑ 1

Example 5.2.9

Simplify each expression: ⓐ 230 ⓑ r0.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 1

ⓑ 1

Use the Definition of a Negative Exponent

We saw that the Quotient Property for Exponents has two forms depending on whether the exponent is larger in the numerator or the denominator. What if we just subtract exponents regardless of which is larger?

Let’s consider x2x5. We subtract the exponent in the denominator from the exponent in the numerator. We see x2x5 is x2−5 or x−3.

We can also simplify x2x5 by dividing out common factors:

This implies that x−3=1x3 and it leads us to the definition of a negative exponent. If n is an integer and a≠0, then a−n=1an.

Let’s now look at what happens to a fraction whose numerator is one and whose denominator is an integer raised to a negative exponent.

1a−nUse the definition of a negative exponent, a−n=1an11anSimplify the complex fraction.1·an1Multiply.an

This implies 1a−n=an and is another form of the definition of Properties of Negative Exponents.

DEFINITION: PROPERTIES OF NEGATIVE EXPONENTS

If n is an integer and a≠0, then a−n=1an or 1a−n=an.

The negative exponent tells us we can rewrite the expression by taking the reciprocal of the base and then changing the sign of the exponent.

Any expression that has negative exponents is not considered to be in simplest form. We will use the definition of a negative exponent and other properties of exponents to write the expression with only positive exponents.

For example, if after simplifying an expression we end up with the expression x−3, we will take one more step and write 1x3. The answer is considered to be in simplest form when it has only positive exponents.

Example 5.2.10

Simplify each expression: ⓐ x−5 ⓑ 10−3 ⓒ 1y−4 ⓓ 13−2.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

x−5Use the definition of a negative exponent, a−n=1an.1x5

ⓑ

10−3Use the definition of a negative exponent, a−n=1an.1103Simplify.11000

ⓒ

1y−4Use the property of a negative exponent, 1a−n=an.y4

ⓓ

13−2Use the property of a negative exponent, 1a−n=an.32Simplify.9

Example 5.2.11

Simplify each expression: ⓐ z−3 ⓑ 10−7 ⓒ 1p−8 ⓓ 14−3.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 1z3 ⓑ 1107 ⓒ p8 ⓓ 64

Example 5.2.12

Simplify each expression: ⓐ n−2 ⓑ 10−4 ⓒ 1q−7 ⓓ 12−4.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 1n2 ⓑ 110,000 ⓒ q7

ⓓ 16

Suppose now we have a fraction raised to a negative exponent. Let’s use our definition of negative exponents to lead us to a new property.

(34)−2Use the definition of a negative exponent, a−n=1an.1(34)2Simplify the denominator.1916Simplify the complex fraction.169But we know that 169 is (43)2.This tells us that(34)−2=(43)2

To get from the original fraction raised to a negative exponent to the final result, we took the reciprocal of the base—the fraction—and changed the sign of the exponent.

This leads us to the Quotient to a Negative Power Property.

QUOTIENT TO A NEGATIVE POWER PROPERTY

If a and b are real numbers, a≠0, b≠0 and n is an integer, then

(ab)−n=(ba)n.

Example 5.2.13

Simplify each expression: ⓐ (57)−2 ⓑ (−xy)−3.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

(57)−2Use the Quotient to a Negative Exponent Property, (ab)−n=(ba)n.Take the reciprocal of the fraction and change the sign of the exponent.(75)2Simplify.4925

ⓑ

(−xy)−3Use the Quotient to a Negative Exponent Property, (ab)−n=(ba)n.Take the reciprocal of the fraction and change the sign of the exponent.(−yx)3Simplify.−y3x3

Example 5.2.14

Simplify each expression: ⓐ (23)−4 ⓑ (−mn)−2.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 8116 ⓑ n2m2

Example 5.2.15

Simplify each expression: ⓐ (35)−3 ⓑ (−ab)−4.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 12527 ⓑ b4a4

Now that we have negative exponents, we will use the Product Property with expressions that have negative exponents.

Example 5.2.16

Simplify each expression: ⓐ z−5·z−3 ⓑ (m4n−3)(m−5n−2) ⓒ (2x−6y8)(−5x5y−3).

- Answer

-

ⓐ

z−5·z−3Add the exponents, since the bases are the same.z−5−3Simplify.z−8Use the definition of a negative exponent.1z8

ⓑ

(m4n−3)(m−5n−2)Use the Commutative Property to get likebases together.m4m−5·n−2n−3Add the exponents for each base.m−1·n−5Take reciprocals and change the signs of the exponents.1m1·1n5Simplify.1mn5

ⓒ

(2x−6y8)(−5x5y−3)Rewrite with the like bases together.2(−5)·(x−6x5)·(y8y−3)Multiply the coefficients and add the exponentsof each variable.−10·x−1·y5Use the definition of a negative exponent,a−n=1an.−10·1x·y5Simplify.−10y5x

Example 5.2.17

Simplify each expression:

ⓐ z−4·z−5 ⓑ (p6q−2)(p−9q−1) ⓒ (3u−5v7)(−4u4v−2).

- Answer

-

ⓐ 1z9 ⓑ 1p3q3 ⓒ −12v5u

Example 5.2.18

Simplify each expression:

ⓐ c−8·c−7 ⓑ (r5s−3)(r−7s−5) ⓒ (−6c−6d4)(−5c−2d−1).

- Answer

-

ⓐ 1c15 ⓑ 1r2s8 ⓒ 30d3c8

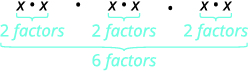

Now let’s look at an exponential expression that contains a power raised to a power. See if you can discover a general property.

(x2)3What does this mean?x2·x2·x2

| How many factors altogether? |  |

| So we have |  |

Notice the 6 is the product of the exponents, 2 and 3. We see that (x2)3 is x2·3 or x6.

We multiplied the exponents. This leads to the Power Property for Exponents.

DEFINITION: POWER PROPERTY FOR EXPONENTS

If a is a real number and m and n are integers, then

(am)n=am·n

To raise a power to a power, multiply the exponents.

Example 5.2.19

Simplify each expression: ⓐ (y5)9 ⓑ (44)7 ⓒ (y3)6(y5)4.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

Use the Power Property, (am)n=am·n.

Simplify.

ⓑ

Use the Power Property.

Simplify.

ⓒ

(y3)6(y5)4Use the Power Property.y18·y20Add the exponents.y38

Example 5.2.20

Simplify each expression: ⓐ (b7)5 ⓑ (54)3 ⓒ (a4)5(a7)4.

- Answer

-

ⓐ b35 ⓑ 512 ⓒ a48

Example 5.2.21

Simplify each expression: ⓐ (z6)9 ⓑ (37)7 ⓒ (q4)5(q3)3.

- Answer

-

ⓐ z54 ⓑ 349 ⓒ q29

We will now look at an expression containing a product that is raised to a power. Can you find this pattern?

(2x)3What does this mean?2x·2x·2xWe group the like factors together.2·2·2·x·x·xHow many factors of 2 and of x23·x3

Notice that each factor was raised to the power and (2x)3 is 23·x3.

The exponent applies to each of the factors! This leads to the Product to a Power Property for Exponents.

DEFINITION: PRODUCT TO A POWER PROPERTY FOR EXPONENTS

If a and b are real numbers and m is a whole number, then

(ab)m=ambm

To raise a product to a power, raise each factor to that power.

Example 5.2.22

Simplify each expression: ⓐ (−3mn)3 ⓑ (−4a2b)0 ⓒ (6k3)−2 ⓓ (5x−3)2.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

Use Power of a Product Property, (ab)m=ambm.

Simplify.

ⓑ

(−4a2b)0Use Power of a Product Property, (ab)m=ambm.(−4)0(a2)0(b)0Simplify.1·1·1Multiply.1

ⓒ

(6k3)−2Use Power of a Product Property, (ab)m=ambm.(6)−2(k3)−2Use the Power Property, (am)n=am·n.6−2k−6Use the Definition of a negative exponent, a−n=1an.162·1k6Simplify.136k6

ⓓ

(5x−3)2Use Power of a Product Property, (ab)m=ambm.52(x−3)2Simplify.25·x−6Rewrite x−6using, a−n=1an.25·1x6Simplify.25x6

Example 5.2.23

Simplify each expression: ⓐ (2wx)5 ⓑ (−11pq3)0 ⓒ (2b3)−4 ⓓ (8a−4)2.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 32w5x5 ⓑ 1 ⓒ 116b12

ⓓ 64a8

Example 5.2.24

Simplify each expression: ⓐ (−3y)3 ⓑ (−8m2n3)0 ⓒ (−4x4)−2 ⓓ (2c−4)3.

- Answer

-

ⓐ −27y3 ⓑ 1 ⓒ 116x8

ⓓ 8c12

Now we will look at an example that will lead us to the Quotient to a Power Property.

(xy)3This meansxy·xy·xyMultiply the fractions.x·x·xy·y·yWrite with exponents.x3y3

Notice that the exponent applies to both the numerator and the denominator.

We see that (xy)3 is x3y3.

This leads to the Quotient to a Power Property for Exponents.

DEFINITION: QUOTIENT TO A POWER PROPERTY FOR EXPONENTS

If a and b are real numbers, b≠0, and m is an integer, then

(ab)m=ambm

To raise a fraction to a power, raise the numerator and denominator to that power.

Example 5.2.25

Simplify each expression:

ⓐ (b3)4 ⓑ (kj)−3 ⓒ (2xy2z)3 ⓓ (4p−3q2)2.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

Use Quotient to a Power Property, (ab)m=ambm.

Simplify.

ⓑ

Raise the numerator and denominator to the power.

Use the definition of negative exponent.

Multiply.

ⓒ

(2xy2z)3Use Quotient to a Power Property, (ab)m=ambm.(2xy2)3z3Use the Product to a Power Property, (ab)m=ambm.8x3y6z3

ⓓ

(4p−3q2)2Use Quotient to a Power Property, (ab)m=ambm.(4p−3)2(q2)2Use the Product to a Power Property, (ab)m=ambm.42(p−3)2(q2)2Simplify using the Power Property, (am)n=am·n.16p−6q4Use the definition of negative exponent.16q4·1p6Simplify.16p6q4

Example 5.2.26

Simplify each expression:

ⓐ (p10)4 ⓑ (mn)−7 ⓒ(3ab3c2)4 ⓓ (3x−2y3)3.

- Answer

-

ⓐ p410000 ⓑ n7m7

ⓒ 81a4b12c8 ⓓ 27x6y9

Example 5.2.27

Simplify each expression:

ⓐ (−2q)3 ⓑ (wx)−4 ⓒ (xy33z2)2 ⓓ (2m−2n−2)3.

- Answer

-

ⓐ −8q3 ⓑ x4w4 ⓒ x2y69z4

ⓓ 8n6m6

We now have several properties for exponents. Let’s summarize them and then we’ll do some more examples that use more than one of the properties.

DEFINITION: SUMMARY OF EXPONENT PROPERTIES

If a and b are real numbers, and m and n are integers, then

| Property | Description |

|---|---|

| Product Property | am·an=am+n |

| Power Property | (am)n=am·n |

| Product to a Power | (ab)n=anbn |

| Quotient Property | aman=am−n,a≠0 |

| Zero Exponent Property | a0=1,a≠0 |

| Quotient to a Power Property | (ab)m=ambm,b≠0 |

| Properties of Negative Exponents | a−n=1an and 1a−n=an |

| Quotient to a Negative Exponent | (ab)−n=(ba)n |

Example 5.2.28

Simplify each expression by applying several properties:

ⓐ (3x2y)4(2xy2)3 ⓑ (x3)4(x−2)5(x6)5 ⓒ (2xy2x3y−2)2(12xy3x3y−1)−1.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

(3x2y)4(2xy2)3Use the Product to a Power Property, (ab)m=ambm.(34x8y4)(23x3y6)Simplify.(81x8y4)(8x3y6)Use the Commutative Property.81·8·x8·x3·y4·y6Multiply the constants and add the exponents.648x11y10

ⓑ

(x3)4(x−2)5(x6)5Use the Power Property, (am)n=am·n.(x12)(x−10)(x30)Add the exponents in the numerator.x2x30Use the Quotient Property, aman=1an−m.1x28

ⓒ

(2xy2x3y−2)2(12xy3x3y−1)−1Simplify inside the parentheses first.(2y4x2)2(12y4x2)−1Use the Quotient to a Power Property, (ab)m=ambm.(2y4)2(x2)2(12y4)−1(x2)−1Use the Product to a Power Property, (ab)m=ambm.4y8x4·12−1y−4x−2Simplify.4y412x2Simplify.y43x2

Example 5.2.29

Simplify each expression:

ⓐ (c4d2)5(3cd5)4 ⓑ (a−2)3(a2)4(a4)5 ⓒ (3xy2x2y−3)2

- Answer

-

ⓐ 81c24d30 ⓑ 1a18

ⓒ 9y10x2

Example 5.2.30

Simplify each expression:

ⓐ (a3b2)6(4ab3)4 ⓑ \dfrac{(p^{−3})^4(p^5)^3}{(p^7)^6} ⓒ \left(\dfrac{4x^3y^2}{x^2y^{−1}}\right)^2\left(\dfrac{8xy^{−3}}{x^2y}\right)^{−1}.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 256a^{22}b^{24} ⓑ \dfrac{1}{p^{39}}

ⓒ 2x^3y^{10}

Use Scientific Notation

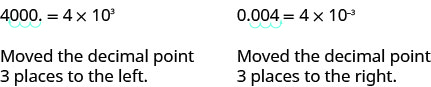

Working with very large or very small numbers can be awkward. Since our number system is base ten we can use powers of ten to rewrite very large or very small numbers to make them easier to work with. Consider the numbers 4,000 and 0.004.

Using place value, we can rewrite the numbers 4,000 and 0.004. We know that 4,000 means 4\times1,000 and 0.004 means 4\times\dfrac{1}{1,000}.

If we write the 1,000 as a power of ten in exponential form, we can rewrite these numbers in this way:

| 4,000 | 4\times1,000 | 4\times103 | |

| 0.004 | 4\times\dfrac{1}{1,000} | 4\times\dfrac{1}{103} | 4\times10^{−3} |

When a number is written as a product of two numbers, where the first factor is a number greater than or equal to one but less than ten, and the second factor is a power of 10 written in exponential form, it is said to be in scientific notation.

DEFINITION: SCIENTIFIC NOTATION

A number is expressed in scientific notation when it is of the form

\begin{array} {llllllllllll} {a} &{\times} &{10^n} &{\text{where}} &{1} &{\leq} &{a} &{<} &{10} &{\text{and}} &{n} &{\text{is an integer.}} \\ \nonumber \end{array}

It is customary in scientific notation to use as the \times multiplication sign, even though we avoid using this sign elsewhere in algebra.

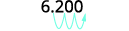

If we look at what happened to the decimal point, we can see a method to easily convert from decimal notation to scientific notation.

In both cases, the decimal was moved 3 places to get the first factor between 1 and 10.

The power of 10 is positive when the number is larger than 1: 4,000=4\times10^3

The power of 10 is negative when the number is between 0 and 1: 0.004=4\times10^{−3}

DEFINITION: TO CONVERT A DECIMAL TO SCIENTIFIC NOTATION.

- Move the decimal point so that the first factor is greater than or equal to 1 but less than 10.

- Count the number of decimal places, n, that the decimal point was moved.

- Write the number as a product with a power of 10. If the original number is.

- greater than 1, the power of 10 will be 10^n.

- between 0 and 1, the power of 10 will be 10^{−n}.

- Check.

EXAMPLE \PageIndex{31}

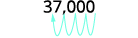

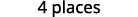

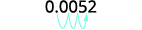

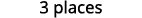

Write in scientific notation: ⓐ 37,000 ⓑ 0.0052.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

The original number, 37,000, is greater than 1

so we will have a positive power of 10.37,000 Move the decimal point to get 3.7, a number

between 1 and 10.

Count the number of decimal places the point

was moved.

Write as a product with a power of 10.

\begin{array} {ll} {} &{3.7\times 10^4 } \\ {\text{Check:}} &{3.7 \times 10,000 } \\ {} &{37,000} \\ \end{array}

ⓑ

The original number, 0.0052, is between 0

and 1 so we will have a negative power of 10.0.0052 Move the decimal point to get 5.2, a number

between 1 and 10.

Count the number of decimal places the point

was moved.

Write as a product with a power of 10.

\begin{array} {ll} {\text{Check:}} &{5.2\times10^{−3}} \\ {} &{5.2\times\dfrac{1}{10^3}} \\ {} &{5.2\times\dfrac{1}{1000}} \\ {} &{5.2\times 0.001} \\ {} &{0.0052} \\ \end{array}

EXAMPLE \PageIndex{32}

Write in scientific notation: ⓐ 96,000 ⓑ 0.0078.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 9.6\times 10^4 ⓑ 7.8\times 10^{−3}

EXAMPLE \PageIndex{33}

Write in scientific notation: ⓐ 48,300 ⓑ 0.0129.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 4.83\times10^4

ⓑ 1.29\times10^{−2}

How can we convert from scientific notation to decimal form? Let’s look at two numbers written in scientific notation and see.

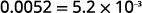

\begin{array} {lll} {9.12\times10^4} &{} &{9.12\times10^{−4}} \\ {9.12\times10,000} &{} &{9.12\times0.0001} \\ {91,200} &{} &{0.000912} \\ \nonumber \end{array}

If we look at the location of the decimal point, we can see an easy method to convert a number from scientific notation to decimal form.

In both cases the decimal point moved 4 places. When the exponent was positive, the decimal moved to the right. When the exponent was negative, the decimal point moved to the left.

DEFINITION: CONVERT SCIENTIFIC NOTATION TO DECIMAL FORM.

- Determine the exponent, n, on the factor 10.

- Move the decimal n places, adding zeros if needed.

- If the exponent is positive, move the decimal point n places to the right.

- If the exponent is negative, move the decimal point |n| places to the left.

- Check.

EXAMPLE \PageIndex{34}

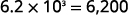

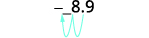

Convert to decimal form: ⓐ 6.2\times10^3 ⓑ −8.9\times 10^{−2}.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

Determine the exponent, n, on the factor 10. The exponent is 3. Since the exponent is positive, move the

decimal point 3 places to the right.

Add zeros as needed for placeholders.

ⓑ

Determine the exponent, n, on the factor 10. The exponent is −2.−2. Since the exponent is negative, move the

decimal point 2 places to the left.

Add zeros as needed for placeholders.

EXAMPLE \PageIndex{35}

Convert to decimal form: ⓐ 1.3\times 10^3 ⓑ −1.2\times 10^{−4}.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 1,300 ⓑ −0.00012

EXAMPLE \PageIndex{36}

Convert to decimal form: ⓐ −9.5\times 10^4 ⓑ 7.5\times 10^{−2}.

- Answer

-

ⓐ −950,000 ⓑ 0.075

When scientists perform calculations with very large or very small numbers, they use scientific notation. Scientific notation provides a way for the calculations to be done without writing a lot of zeros. We will see how the Properties of Exponents are used to multiply and divide numbers in scientific notation.

EXAMPLE \PageIndex{37}

Multiply or divide as indicated. Write answers in decimal form: ⓐ (−4\times10^5)(2\times10^{−7}) ⓑ \dfrac{9\times10^3}{3\times10^{−2}}.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

\begin{array} {ll} {} &{(−4\times10^5)(2\times10^{−7})} \\ {\text{Use the Commutative Property to rearrange the factors.}} &{−4·2·10^5·10^{−7}} \\ {\text{Multiply.}} &{−8\times10^{−2}} \\ {} &{} \\ {\text{Change to decimal form by moving the decimal two}} &{} \\ {\text{places left.}} &{−0.08} \\ \end{array}

ⓑ

\begin{array} {ll} {} &{\dfrac{9\times10^3}{9\times10^{−2}}} \\ {\text{Separate the factors, rewriting as the product of two}} &{} \\ {\text{fractions.}} &{\dfrac{9}{3}\times\dfrac{10^3}{10^{−2}}} \\ {\text{Divide.}} &{3\times10^5} \\ {\text{Change to decimal form by moving the decimal five}} &{} \\ {\text{places right.}} &{300,000} \\ \end{array}

EXAMPLE \PageIndex{38}

Multiply or divide as indicated. Write answers in decimal form:

ⓐ (−3\times10^5)(2\times10^{−8}) ⓑ \dfrac{8\times10^2}{4\times10^{−2}}.

- Answer

-

ⓐ −0.006 ⓑ 20,000

EXAMPLE \PageIndex{39}

Multiply or divide as indicated. Write answers in decimal form:

ⓐ (−3\times10^{−2})(3\times10^{−1}) ⓑ \dfrac{8\times10^4}{2\times10^{−1}}.

- Answer

-

ⓐ −0.009 ⓑ 400,000

Access these online resources for additional instruction and practice with using multiplication properties of exponents.

- Properties of Exponents

- Negative exponents

- Scientific Notation

Key Concepts

- Exponential Notation

This is read a to the m^{th} power.

In the expression a^m, the exponent m tells us how many times we use the base a as a factor. - Product Property for Exponents

If a is a real number and m and n are integers, thena^m·a^n=a^{m+n} \nonumber

To multiply with like bases, add the exponents. - Quotient Property for Exponents

If a is a real number, a\neq 0, and m and n are integers, then\begin{array} {lllll} {\dfrac{a^m}{a^n}=a^{m−n},} &{m>n} &{\text{and}} &{\dfrac{a^m}{a^n}=\dfrac{1}{a^{n−m}},} &{n>m}\\ \nonumber \end{array}

- Zero Exponent

- If a is a non-zero number, then a^0=1.

- If a is a non-zero number, then a to the power of zero equals 1.

- Any non-zero number raised to the zero power is 1.

- Negative Exponent

- If n is an integer and a\neq 0, then a^{−n}=\dfrac{1}{a^n} or \dfrac{1}{a^{−n}}=a^n.

- Quotient to a Negative Exponent Property

If a and b are real numbers, a\neq 0, b\neq 0 and n is an integer, then(ab)^{−n}=(ba)^n\nonumber

- Power Property for Exponents

If a is a real number and m and n are integers, then(a^m)^n=a^{m·n}\nonumber

To raise a power to a power, multiply the exponents. - Product to a Power Property for Exponents

If a and b are real numbers and m is a whole number, then(ab)^m=a^mb^m \nonumber

To raise a product to a power, raise each factor to that power. - Quotient to a Power Property for Exponents

If a and b are real numbers, b\neq0, and m is an integer, then\left(\dfrac{a}{b}\right)^m=\dfrac{a^m}{b^m} \nonumber

To raise a fraction to a power, raise the numerator and denominator to that power. - Summary of Exponent Properties

If a and b are real numbers, and m and n are integers, thenProperty Description Product Property a^m·a^n=a^{m+n} Power Property (a^m)^n=a^{m·n} Product to a Power (ab)^n=a^nb^n Quotient Property \dfrac{a^m}{a^n}=a^{m−n}, a\neq 0 Zero Exponent Property a^0=1,a\neq 0 Quotient to a Power Property: \left(\dfrac{a}{b}\right)^m=\dfrac{a^m}{b^m}, b\neq 0 Properties of Negative Exponents a^{−n}=\dfrac{1}{a^n} and \dfrac{1}{a^{−n}}=a^n Quotient to a Negative Exponent \left(\dfrac{a}{b}\right)^{−n}=\left(\dfrac{b}{a}\right)^n - Scientific Notation

A number is expressed in scientific notation when it is of the forma\space\times\space10^n \text{ where }1\leq a<10\text{ and } n \text{ is an integer.} \nonumber

- How to convert a decimal to scientific notation.

- Move the decimal point so that the first factor is greater than or equal to 1 but less than 10.

- Count the number of decimal places, n, that the decimal point was moved.

- Write the number as a product with a power of 10. If the original number is.

- greater than 1, the power of 10 will be 10^n.

- between 0 and 1, the power of 10 will be 10^{−n}.

- Check.

- How to convert scientific notation to decimal form.

- Determine the exponent, n, on the factor 10.

- Move the decimal n places, adding zeros if needed.

- If the exponent is positive, move the decimal point n places to the right.

- If the exponent is negative, move the decimal point |n| places to the left.

- Check.

Glossary

- Product Property

- According to the Product Property, a to the m times a to the a equals a to the m plus n.

- Power Property

- According to the Power Property, a to the m to the n equals a to the m times n.

- Product to a Power

- According to the Product to a Power Property, a times b in parentheses to the m equals a to the m times b to the m.

- Quotient Property

- According to the Quotient Property, a to the m divided by a to the n equals a to the m minus n as long as a is not zero.

- Zero Exponent Property

- According to the Zero Exponent Property, a to the zero is 1 as long as a is not zero.

- Quotient to a Power Property

- According to the Quotient to a Power Property, a divided by b in parentheses to the power of m is equal to a to the m divided by b to the m as long as b is not zero.

- Properties of Negative Exponents

- According to the Properties of Negative Exponents, a to the negative n equals 1 divided by a to the n and 1 divided by a to the negative n equals a to the n.

- Quotient to a Negative Exponent

- Raising a quotient to a negative exponent occurs when a divided by b in parentheses to the power of negative n equals b divided by a in parentheses to the power of n.