7.1: Review of Power Series

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 30747

Many applications give rise to differential equations with solutions that can’t be expressed in terms of elementary functions such as polynomials, rational functions, exponential and logarithmic functions, and trigonometric functions. The solutions of some of the most important of these equations can be expressed in terms of power series. We’ll study such equations in this chapter. In this section we review relevant properties of power series. We’ll omit proofs, which can be found in any standard calculus text.

Definition 7.2.1

An infinite series of the form

\[\label{eq:7.1.1} \sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n,\]

where \(x_0\) and \(a_0\), \(a_1,\) …, \(a_n,\) …are constants, is called a power series in \(x-x_0.\) We say that the power series Equation \ref{eq:7.1.1} converges for a given \(x\) if the limit

\[\lim_{N\to\infty} \sum_{n=0}^Na_n(x-x_0)^n \nonumber\]

exists\(;\) otherwise, we say that the power series diverges for the given \(x.\)

A power series in \(x-x_0\) must converge if \(x=x_0\), since the positive powers of \(x-x_0\) are all zero in this case. This may be the only value of \(x\) for which the power series converges. However, the next theorem shows that if the power series converges for some \(x\ne x_0\) then the set of all values of \(x\) for which it converges forms an interval.

Theorem 7.2.2

For any power series

\[\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n, \nonumber\]

exactly one of the these statements is true:

- The power series converges only for \(x=x_0.\)

- The power series converges for all values of \(x.\)

- There’s a positive number \(R\) such that the power series converges if \(|x-x_0|<R\) and diverges if \(|x-x_{0}|>R\).

In case (iii) we say that \(R\) is the radius of convergence of the power series. For convenience, we include the other two cases in this definition by defining \(R=0\) in case (i) and \(R=\infty\) in case (ii). We define the open interval of convergence of \(\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n\) to be

\[(x_{0}-R, x_{0}+R)\quad\text{if}\quad 0<R<\infty ,\quad\text{or}\quad (-\infty, \infty )\quad\text{if}\quad R=\infty \nonumber.\]

If \(R\) is finite, no general statement can be made concerning convergence at the endpoints \(x=x_0\pm R\) of the open interval of convergence; the series may converge at one or both points, or diverge at both.

Recall from calculus that a series of constants \(\sum_{n=0}^\infty\alpha_n\) is said to converge absolutely if the series of absolute values \(\sum_{n=0}^\infty|\alpha_n|\) converges. It can be shown that a power series \(\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n\) with a positive radius of convergence \(R\) converges absolutely in its open interval of convergence; that is, the series

\[\sum_{n=0}^\infty |a_n||x-x_0|^n \nonumber\]

of absolute values converges if \(|x-x_0| <R\). However, if \(R<\infty\), the series may fail to converge absolutely at an endpoint \(x_{0}\pm R\), even if it converges here.

The next theorem provides a useful method for determining the radius of convergence of a power series. It’s derived in calculus by applying the ratio test to the corresponding series of absolute values. For related theorems see Exercises 7.2.2 and 7.2.4.

Theorem 7.2.3

Suppose there’s an integer \(N\) such that \(a_n\ne0\) if \(n\ge N\) and

\[\lim_{n\to\infty}\left|a_{n+1}\over a_n\right|=L, \nonumber\]

where \(0\le L\le\infty.\) Then the radius of convergence of \(\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n\) is \(R=1/ L,\) which should be interpreted to mean that \(R=0\) if \(L=\infty,\) or \(R=\infty\) if \(L=0\).

Example 7.2.1

Find the radius of convergence of the series:

- \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^\infty n!x^n \nonumber\)

- \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=10}^\infty (-1)^n {x^n\over n!} \nonumber\)

- \(\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^\infty 2^nn^2 (x-1)^n.\nonumber\)

Solution a

Here \(a_n=n!\), so

\[\lim_{n\to\infty}\left|a_{n+1}\over a_n\right|=\lim_{n\to\infty} {(n+1)!\over n!}=\lim_{n\to\infty}(n+1)=\infty. \nonumber\]

Hence, \(R=0\).

Solution b

Here \(a_n=(1)^n/n!\) for \(n\ge N=10\), so

\[\lim_{n\to\infty}\left|a_{n+1}\over a_n\right|=\lim_{n\to\infty} {n!\over (n+1)!}=\lim_{n\to\infty}{1\over n+1}=0. \nonumber\]

Hence, \(R=\infty\).

Solution c

Here \(a_n=2^nn^2\), so

\[\lim_{n\to\infty}\left|a_{n+1}\over a_n\right|=\lim_{n\to\infty} {2^{n+1}(n+1)^2\over2^nn^2}=2\lim_{n\to\infty}\left(1+{1\over n}\right)^2=2. \nonumber\]

Hence, \(R=1/2\).

Taylor Series

If a function \(f\) has derivatives of all orders at a point \(x=x_0\), then the Taylor series of \(f\) about \(x_0\) is defined by

\[\sum_{n=0}^\infty {f^{(n)}(x_0)\over n!}(x-x_0)^n. \nonumber \]

In the special case where \(x_0=0\), this series is also called the Maclaurin series of \(f\).

Taylor series for most of the common elementary functions converge to the functions on their open intervals of convergence. For example, you are probably familiar with the following Maclaurin series:

\[\begin{align} \label{eq:7.1.2} e^{x} &= \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{x^{n}}{n!}, \quad -\infty<x<\infty \\[4pt] \label{eq:7.1.3} \sin x &= \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (-1)^{n} \frac{x^{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!}, \quad -\infty<x<\infty \\[4pt] \label{eq:7.1.4} \cos x &= \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (-1)^{n} \frac{x^{2n}}{(2n)!} \quad -\infty<x<\infty \\[4pt] \label{eq:7.1.5} \frac{1}{1-x} &= \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} x^{n} \quad -1<x<1 \end{align}\]

Differentiation of Power Series

A power series with a positive radius of convergence defines a function

\[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n \nonumber\]

on its open interval of convergence. We say that the series represents \(f\) on the open interval of convergence. A function \(f\) represented by a power series may be a familiar elementary function as in Equations \ref{eq:7.1.2} - \ref{eq:7.1.5}; however, it often happens that \(f\) isn’t a familiar function, so the series actually defines \(f\).

The next theorem shows that a function represented by a power series has derivatives of all orders on the open interval of convergence of the power series, and provides power series representations of the derivatives.

Theorem 7.2.4 : A Power Series

A power series

\[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n \nonumber\]

with positive radius of convergence \(R\) has derivatives of all orders in its open interval of convergence, and successive derivatives can be obtained by repeatedly differentiating term by term\(;\) that is,

\[\begin{align} f'(x)&={\sum_{n=1}^\infty na_n(x-x_0)^{n-1}}\label{eq:7.1.6},\\[4pt] f''(x)&={\sum_{n=2}^\infty n(n-1)a_n(x-x_0)^{n-2}},\label{eq:7.1.7}\\[4pt] &\vdots&\nonumber\\ f^{(k)}(x)&={\sum_{n=k}^\infty n(n-1)\cdots(n-k+1)a_n(x-x_0)^{n-k}}\label{eq:7.1.8}.\end{align}\nonumber \]

Moreover, all of these series have the same radius of convergence \(R.\)

Example 7.2.2

Let \(f(x)=\sin x\). From Equation \ref{eq:7.1.3},

\[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty(-1)^n {x^{2n+1}\over(2n+1)!}. \nonumber\]

From Equation \ref{eq:7.1.6},

\[f'(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty(-1)^n{d\over dx}\left[x^{2n+1}\over(2n+1)!\right]= \sum_{n=0}^\infty(-1)^n {x^{2n}\over(2n)!}, \nonumber\]

which is the series Equation \ref{eq:7.1.4} for \(\cos x\).

Uniqueness of Power Series

The next theorem shows that if \(f\) is defined by a power series in \(x-x_0\) with a positive radius of convergence, then the power series is the Taylor series of \(f\) about \(x_0\).

Theorem 7.2.5

If the power series

\[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n \nonumber\]

has a positive radius of convergence, then

\[\label{eq:7.1.9} a_n={f^{(n)}(x_0)\over n!};\]

that is, \(\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n\) is the Taylor series of \(f\) about \(x_0\).

This result can be obtained by setting \(x=x_0\) in Equation \ref{eq:7.1.8}, which yields

\[f^{(k)}(x_0)=k(k-1)\cdots1\cdot a_k=k!a_k. \nonumber\]

This implies that

\[a_k={f^{(k)}(x_0)\over k!}.\nonumber\]

Except for notation, this is the same as Equation \ref{eq:7.1.9}.

The next theorem lists two important properties of power series that follow from Theorem 7.2.4 .

Theorem 7.2.6

- If \[\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n=\sum_{n=0}^\infty b_n(x-x_0)^n\nonumber \] for all \(x\) in an open interval that contains \(x_0,\) then \(a_n=b_n\) for \(n=0\), \(1\), \(2\), ….

- If \[\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n=0\nonumber \] for all \(x\) in an open interval that contains \(x_0,\) then \(a_n=0\) for \(n=0\), \(1\), \(2\), ….

To obtain (a) we observe that the two series represent the same function \(f\) on the open interval; hence, Theorem 7.2.4 implies that

\[a_n=b_n={f^{(n)}(x_0)\over n!},\quad n=0,1,2, \dots. \nonumber\]

(b) can be obtained from (a) by taking \(b_n=0\) for \(n=0\), \(1\), \(2\), ….

Taylor Polynomials

If \(f\) has \(N\) derivatives at a point \(x_0\), we say that

\[T_N(x)=\sum_{n=0}^N{f^{(n)}(x_0)\over n!}(x-x_0)^n \nonumber\]

is the \(N\)-th Taylor polynomial of \(f\) about \(x_0\). This definition and Theorem 7.2.4 imply that if

\[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n, \nonumber\]

where the power series has a positive radius of convergence, then the Taylor polynomials of \(f\) about \(x_0\) are given by

\[T_N(x)=\sum_{n=0}^N a_n(x-x_0)^n. \nonumber\]

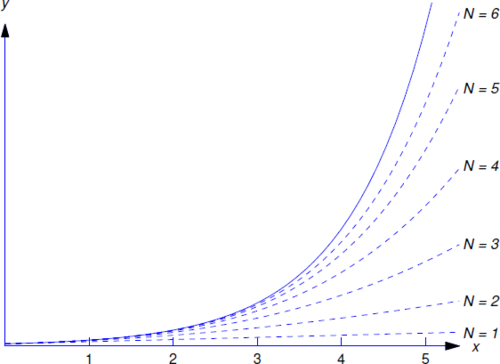

In numerical applications, we use the Taylor polynomials to approximate \(f\) on subintervals of the open interval of convergence of the power series. For example, Equation \ref{eq:7.1.2} implies that the Taylor polynomial \(T_N\) of \(f(x)=e^x\) is

\[T_N(x)=\sum_{n=0}^N{x^n\over n!}. \nonumber\]

The solid curve in Figure 7.2.1 is the graph of \(y=e^x\) on the interval \([0,5]\). The dotted curves in Figure 7.2.1 are the graphs of the Taylor polynomials \(T_1\), …, \(T_6\) of \(y=e^x\) about \(x_0=0\). From this figure, we conclude that the accuracy of the approximation of \(y=e^x\) by its Taylor polynomial \(T_N\) improves as \(N\) increases.

Shifting the Summation Index

In Definition 7.2.1 of a power series in \(x-x_0\), the \(n\)-th term is a constant multiple of \((x-x_0)^n\). This isn’t true in Equation \ref{eq:7.1.6}, Equation \ref{eq:7.1.7}, and Equation \ref{eq:7.1.8}, where the general terms are constant multiples of \((x-x_0)^{n-1}\), \((x-x_0)^{n-2}\), and \((x-x_0)^{n-k}\), respectively. However, these series can all be rewritten so that their \(n\)-th terms are constant multiples of \((x-x_0)^n\). For example, letting \(n=k+1\) in the series in Equation \ref{eq:7.1.6} yields

\[\label{eq:7.1.10} f'(x)=\sum_{k=0}^\infty (k+1)a_{k+1}(x-x_0)^k,\]

where we start the new summation index \(k\) from zero so that the first term in Equation \ref{eq:7.1.10} (obtained by setting \(k=0\)) is the same as the first term in Equation \ref{eq:7.1.6} (obtained by setting \(n=1\)). However, the sum of a series is independent of the symbol used to denote the summation index, just as the value of a definite integral is independent of the symbol used to denote the variable of integration. Therefore we can replace \(k\) by \(n\) in Equation \ref{eq:7.1.10} to obtain

\[\label{eq:7.1.11} f'(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty (n+1)a_{n+1}(x-x_0)^n,\]

where the general term is a constant multiple of \((x-x_0)^n\).

It isn’t really necessary to introduce the intermediate summation index \(k\). We can obtain Equation \ref{eq:7.1.11} directly from Equation \ref{eq:7.1.6} by replacing \(n\) by \(n+1\) in the general term of Equation \ref{eq:7.1.6} and subtracting 1 from the lower limit of Equation \ref{eq:7.1.6}. More generally, we use the following procedure for shifting indices.

Shifting the Summation Index in a Power Series

For any integer \(k\), the power series

\[\sum _ { n = n _ { 0 } } ^ { \infty } b _ { n } \left( x - x _ { 0 } \right) ^ { n - k } \nonumber \]

can be rewritten as

\[\sum _ { n = n _ { 0 } - k } ^ { \infty } b _ { n + k } \left( x - x _ { 0 } \right) ^ { n } \nonumber \]

that is, replacing \(n\) by \(n + k\) in the general term and subtracting k from the lower limit of summation leaves the series unchanged.

Example 7.2.3

Rewrite the following power series from Equation \ref{eq:7.1.7} and Equation \ref{eq:7.1.8} so that the general term in each is a constant multiple of \((x-x_0)^n\):

\[(a) \sum_{n=2}^\infty n(n-1)a_n(x-x_0)^{n-2}\quad (b) \sum_{n=k}^\infty n(n-1)\cdots(n-k+1)a_n(x-x_0)^{n-k}. \nonumber \]

Solution a

Replacing \(n\) by \(n+2\) in the general term and subtracting \(2\) from the lower limit of summation yields

\[\sum_{n=2}^\infty n(n-1)a_n(x-x_0)^{n-2}= \sum_{n=0}^\infty (n+2)(n+1)a_{n+2}(x-x_0)^n. \nonumber \]

Solution b

Replacing \(n\) by \(n+k\) in the general term and subtracting \(k\) from the lower limit of summation yields

\[\sum_{n=k}^\infty n(n-1)\cdots(n-k+1)a_n(x-x_0)^{n-k}= \sum_{n=0}^\infty (n+k)(n+k-1)\cdots(n+1)a_{n+k}(x-x_0)^n. \nonumber \]

Example 7.2.4

Given that

\[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_nx^n, \nonumber\]

write the function \(xf''\) as a power series in which the general term is a constant multiple of \(x^n\).

Solution

From Theorem 7.2.4 with \(x_0=0\),

\[f''(x)=\sum_{n=2}^\infty n(n-1)a_nx^{n-2}.\nonumber\]

Therefore

\[xf''(x)=\sum_{n=2}^\infty n(n-1)a_nx^{n-1}.\nonumber\]

Replacing \(n\) by \(n+1\) in the general term and subtracting \(1\) from the lower limit of summation yields

\[xf''(x)=\sum_{n=1}^\infty (n+1)na_{n+1}x^n.\nonumber\]

We can also write this as

\[xf''(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty (n+1)na_{n+1}x^n,\nonumber\]

since the first term in this last series is zero. (We’ll see later that sometimes it is useful to include zero terms at the beginning of a series.)

Linear Combinations of Power Series

If a power series is multiplied by a constant, then the constant can be placed inside the summation; that is,

\[c\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n=\sum_{n=0}^\infty ca_n(x-x_0)^n.\nonumber\]

Two power series

\[f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n \quad\mbox{ and }\quad g(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty b_n(x-x_0)^n\nonumber\]

with positive radii of convergence can be added term by term at points common to their open intervals of convergence; thus, if the first series converges for \(|x-x_0|<R_{1}\) and the second converges for \(|x-x_{0}|<R_{2}\), then

\[f(x)+g(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty(a_n+b_n)(x-x_0)^n\nonumber\]

for \(|x-x_0|<R\), where \(R\) is the smaller of \(R_{1}\) and \(R_{2}\). More generally, linear combinations of power series can be formed term by term; for example,

\[c_1f(x)+c_2f(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty(c_1a_n+c_2b_n)(x-x_0)^n.\nonumber\]

Example 7.2.5

Find the Maclaurin series for \(\cosh x\) as a linear combination of the Maclaurin series for \(e^x\) and \(e^{-x}\).

Solution

By definition,

\[\cosh x={1\over2}e^x+{1\over2}e^{-x}. \nonumber\]

Since

\[e^x=\sum_{n=0}^\infty {x^n\over n!}\quad\mbox{ and }\quad e^{-x}=\sum_{n=0}^\infty (-1)^n {x^n\over n!}, \nonumber\]

it follows that

\[\label{eq:7.1.12} \cosh x=\sum_{n=0}^\infty {1\over2}[1+(-1)^n]{x^n\over n!}.\]

Since

\[{1\over2}[1+(-1)^n]=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}1&\mbox{ if } n=2m,\mbox{ an even integer},\\ 0&\mbox{ if }n=2m+1,\mbox{ an odd integer}, \end{array}\right. \nonumber\]

we can rewrite Equation \ref{eq:7.1.12} more simply as

\[\cosh x=\sum_{m=0}^\infty{x^{2m}\over(2m)!}. \nonumber\]

This result is valid on \((-\infty,\infty)\), since this is the open interval of convergence of the Maclaurin series for \(e^x\) and \(e^{-x}\).

Example 7.2.6

Suppose

\[y=\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n x^n \nonumber\]

on an open interval \(I\) that contains the origin.

- Express \[(2-x)y''+2y \nonumber\] as a power series in \(x\) on \(I\).

- Use the result of (a) to find necessary and sufficient conditions on the coefficients \(\{a_n\}\) for \(y\) to be a solution of the homogeneous equation

\[\label{eq:7.1.13} (2-x)y''+2y=0\]

on \(I\).

Solution a

From Equation \ref{eq:7.1.7} with \(x_0=0\),

\[y''=\sum_{n=2}^\infty n(n-1)a_nx^{n-2}. \nonumber\]

Therefore

\[\label{eq:7.1.14} \begin{array}{rcl} (2-x)y''+2y &= 2y''-xy'+2y\\ &= {\sum_{n=2}^\infty 2n(n-1)a_nx^{n-2} -\sum_{n=2}^\infty n(n-1)a_nx^{n-1} +\sum_{n=0}^\infty 2a_n x^n}. \end{array}\]

To combine the three series we shift indices in the first two to make their general terms constant multiples of \(x^n\); thus,

\[\label{eq:7.1.15} \sum_{n=2}^\infty 2n(n-1)a_nx^{n-2}=\sum_{n=0}^\infty2(n+2)(n+1)a_{n+2}x^n\]

and

\[\label{eq:7.1.16} \sum_{n=2}^\infty n(n-1)a_nx^{n-1}=\sum_{n=1}^\infty(n+1)na_{n+1}x^n =\sum_{n=0}^\infty(n+1)na_{n+1}x^n,\]

where we added a zero term in the last series so that when we substitute from Equation \ref{eq:7.1.15} and Equation \ref{eq:7.1.16} into Equation \ref{eq:7.1.14} all three series will start with \(n=0\); thus,

\[\label{eq:7.1.17} (2-x)y''+2y=\sum_{n=0}^\infty [2(n+2)(n+1)a_{n+2}-(n+1)na_{n+1}+2a_n]x^n.\]

Solution b

From Equation \ref{eq:7.1.17} we see that \(y\) satisfies Equation \ref{eq:7.1.13} on \(I\) if

\[\label{eq:7.1.18} 2(n+2)(n+1)a_{n+2}-(n+1)na_{n+1}+2a_n=0,\quad n=0,1,2, \dots.\]

Conversely, Theorem 7.2.5 b implies that if \(y=\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_nx^n\) satisfies Equation \ref{eq:7.1.13} on \(I\), then Equation \ref{eq:7.1.18} holds.

Example 7.2.7

Suppose

\[y=\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n (x-1)^n \nonumber\]

on an open interval \(I\) that contains \(x_0=1\). Express the function

\[\label{eq:7.1.19} (1+x)y''+2(x-1)^2y'+3y\]

as a power series in \(x-1\) on \(I\).

Solution

Since we want a power series in \(x-1\), we rewrite the coefficient of \(y''\) in Equation \ref{eq:7.1.19} as \(1+x=2+(x-1)\), so Equation \ref{eq:7.1.19} becomes

\[2y''+(x-1)y''+2(x-1)^2y'+3y. \nonumber\]

From Equation \ref{eq:7.1.6} and Equation \ref{eq:7.1.7} with \(x_0=1\),

\[y'=\sum_{n=1}^\infty na_n(x-1)^{n-1}\quad\mbox{ and }\quad y ''=\sum_{n=2}^\infty n(n-1)a_n(x-1)^{n-2}. \nonumber\]

Therefore

\[\begin{aligned} 2y '' &= \sum_{n=2}^\infty 2n(n-1)a_n(x-1)^{n-2},\\ (x-1)y '' &= \sum_{n=2}^\infty n(n-1)a_n(x-1)^{n-1},\\ 2(x-1)^2y' &= \sum_{n=1}^\infty2na_n(x-1)^{n+1},\\ 3y &= \sum_{n=0}^\infty 3a_n (x-1)^n.\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Before adding these four series we shift indices in the first three so that their general terms become constant multiples of \((x-1)^n\). This yields

\[\begin{align} 2y'' &= \sum_{n=0}^\infty 2(n+2)(n+1)a_{n+2}(x-1)^n,\label{eq:7.1.20}\\ (x-1)y'' &= \sum_{n=0}^\infty (n+1)na_{n+1}(x-1)^n, \label{eq:7.1.21}\\ 2(x-1)^2y' &= \sum_{n=1}^\infty 2(n-1)a_{n-1}(x-1)^n,\label{eq:7.1.22}\\ 3y &= \sum_{n=0}^\infty 3a_n (x-1)^n, \label{eq:7.1.23}\end{align}\]

where we added initial zero terms to the series in Equation \ref{eq:7.1.21} and Equation \ref{eq:7.1.22}. Adding Equations \ref{eq:7.1.20}–\ref{eq:7.1.23} yields

\[\begin{aligned} (1+x)y''+2(x-1)^2y'+3y &= 2y''+(x-1)y''+2(x-1)^2y'+3y\\ &= \sum_{n=0}^\infty b_n (x-1)^n,\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

where

\[\begin{align} b_0 &= 4a_2+3a_0, \label{eq:7.1.24}\\[4pt] b_n &= 2(n+2)(n+1)a_{n+2}+(n+1)na_{n+1}+2(n-1)a_{n-1}+3a_n,\, n\ge1\label{eq:7.1.25}.\end{align}\]

The formula Equation \ref{eq:7.1.24} for \(b_0\) can’t be obtained by setting \(n=0\) in Equation \ref{eq:7.1.25}, since the summation in Equation \ref{eq:7.1.22} begins with \(n=1\), while those in Equation \ref{eq:7.1.20}, Equation \ref{eq:7.1.21}, and Equation \ref{eq:7.1.23} begin with \(n=0\).