4.4: On Special Groups

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

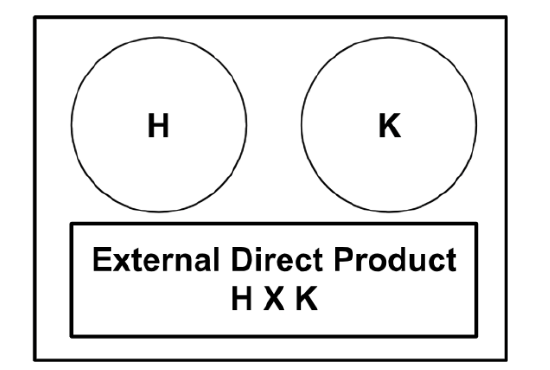

External Direct Product

Let (G, \star) and (G, \diamond) be groups.

Then the external direct product is defined by G_1 \times G_2=\{(g_1,g_2) | g_1 \in G_1, g_2 \in G_2\}. (g_1, g_2)(h_1,h_2)=(g_1\star h_1, g_2 \diamond h_2).

Consider the following

(\mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2, +\pmod{2}).

|

Cayley Table (\mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2, +\pmod{2}) |

||||

|

+\pmod{2} |

(0,0) |

(0,1) |

(1,0) |

(1,1) |

|

(0,0) |

(0,0) |

(0,1) |

(1,0) |

(1,1) |

|

(0,1) |

(0,1) |

(0,0) |

(1,1) |

(1,0) |

|

(1,0) |

(1,0) |

(1,1) |

(0,0) |

(0,1) |

|

(1,1) |

(1,1) |

(1,0) |

(0,1) |

(0,0) |

Notice that | \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2| =4, and every element which is not the identity has order 2. Therefore, the abelian group \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2 is not isomorphic to the cyclic group \mathbb{Z}_4.

If you have many groups G_i, i=1, \cdots n , then the external direct product can be written as \displaystyle\prod_{i=1}^{n} G_{i}.

Consider the following:

( \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_3, +(mod 6)).

\mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_3 = \{(0,0),(0,1),(0,2),(1,0),(1,1),(1,2)\}.

Notice that (1,1)^6(mod \, 2)=(0,0). Therefore \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_3 = \langle (1,1) \rangle . Hence \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_3 is a cyclic group of order 6. Therefore, \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_3 \cong \mathbb{Z}_6.

The group \mathbb{Z}_m \times \mathbb{Z}_n \cong \mathbb{Z}_{mn} iff gcd(m,n)=1.

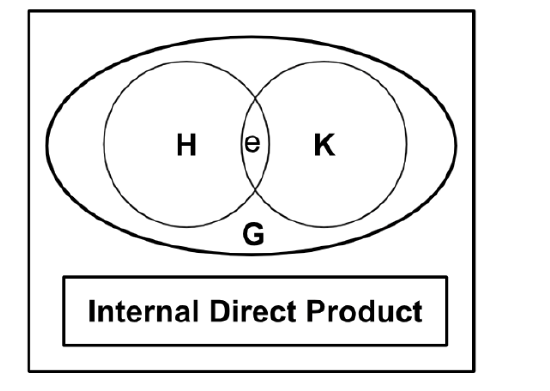

Internal Direct Product

Let G be a group with subgroups H and K , with the following conditions satisfied:

-

H\le G and K \le G.

-

G=HK=\{hk|h\in H, k \in K\}

-

H \cap K =\{e\}.

-

hk=kh, \; \forall h \in H, \; k \in K.

Then we say that G is the internal direct product of H and K .

H=\{1,3\}, K=\{1,5\}, G = U(8)=\{1,3,5,7\}. Is G=HK?

Yes.

Proof:

Let H=\{1,3\}, K=\{1,5\}, G = U(8)=\{1,3,5,7\}.

We will show H \le G and K \le G.

H \subseteq G, e_H=e, ab^{-1} \in H thus H \le G.

Similarly, K \le G.

H \cap K=\{e\} by inspection.

We will show hk=kh, \; \forall h \in H, k \in K.

Consider 1\cdot 1=1\cdot 1=1 \in G

1\cdot 5=5\cdot 1=5 \in G

3\cdot 1=1\cdot 3=3 \in G

3\cdot 5=5\cdot 3=7 \in G

Thus G=HK .◻

Let G=D_6= \langle r,s|r^6=e, s^2=e,r^{-1}sr=s^{-1} \rangle .

Let H=\{e,r^3\} , K=\{e,r^2,r^4,s,r^2s,r^4s\} .

Is G=HK ?

H \le G and K \le G .

H \cap K=\{e\} .

By inspection, hk=kh, \forall k \in K, h \in H .

Thus G=HK .