4.3: 3-D Geometry

- Page ID

- 4892

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Thinking Out Loud

When you slice an orange, what type of shape(s) can occur?

Polyhedra

Definition: Polyhedra

Polyhedra (pl.) are simple closed surfaces that are composed of polygonal regions.

A polyhedron (sg.) has a number of:

- Vertices - corners where various edges and polygonal corners meet

- Edges - lines where two polygonal edges meet

- Faces - the proper name for polygonal regions which compose a polyhedron

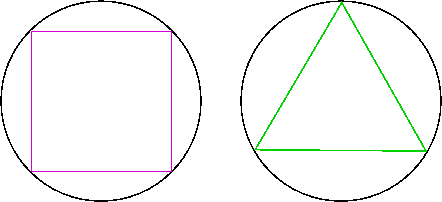

Polyhedra may be:

- Convex - shapes that follow the convex property of 2-dimensional geometry in 3-dimensional space.

- Concave - shapes that follow the concave property of 2-dimensional geometry in 3-dimensional space.

Nets are used when constructing polyhedra out of a single, contiguous, piece of material. The various polygons are laid out together, edges touching, to be cut out and folded together.

Polyhedra are said to be prisms if they have bases which are congruent and parallel polygons

Pyramids

Definition: Pyramids

Pyramids are created by joining a polygonal base to a point above it, called an apex. Each edge of the base, when joined by its vertices to the apex, creates a series of congruent triangles around the shape.

The more edges the base has, the more a pyramid approximates a cone.

Thinking Out Loud:

The sphere is the most symmetrical solid in space. Building a sphere isn’t easy, so what other solids might we construct to approximate its symmetry? In order to construct a solid with lots of symmetry, we suppose our solid has flat sides and straight edges. What properties would such solids have in order to be symmetrical as possible?

Regular Polyhedra

Definition: Regular polyhedra (Platonic solids)

A polyhedron is said to be regular if:

- All of its faces are congruent

- All of its vertices join the same number of edges

- All of its edges join only two faces

Regular polyhedra are also called the Platonic solids.

Thinking Out Loud:

How many regular polyhedra are possible? How can you prove it?

ACTIVITY

Activity: Appreciate polygons and support the idea that there are exactly \(5\) platonic solids.

Suppose we want to tape regular n-gons together to make 3-dimensional shapes. We can make a cube, for example, by taping squares together. What are our options? We don’t want to bend or fold the n-gons. Let’s just concentrate on the corners of these objects.

Fact: To make a corner we’ll need at least 3 regular n-gons.

Try making corners out of 3 n-gons. Which ones will work? Justify your conclusions.

Now try using four n-gons to make corners. Which ones will work? Justify your conclusions.

What about using five n-gons? Justify your conclusions.

Can we make corners out of six or more n-gons? Justify your conclusions.

A platonic solid is a 3-dimensional object made by taping together regular n-gons in such a way that each corner is the same, and has the same number of n-gons around it. Using the data you’ve gathered, please complete the following statement:

I have found that there are ____________ ways to tape regular n-gons together to make the corners of a platonic solid. Therefore, there are at most __________ platonic solids.

Video Demonstration can be found here.

Tetrahedron

Definition: tetrahedron

A tetrahedron is a Platonic solid with:

- 4 faces

- 4 vertices

- 6 edges

The tetrahedron is bounded by four equilateral triangles and has the smallest volume for its surface area of the Platonic solids.

In Ancient Greece, a tetrahedron represents the property of dryness and corresponds to the element of Fire.

Cube (hexahedron)

Definition: Cube

A cube, or hexahedron, is a Platonic solid with:

- 6 faces

- 8 vertices

- 12 edges

The cube is bounded by six squares.

In Ancient Greece, the cube, standing firmly on its base, corresponds to the element of Earth.

Octahedron

Definition: Octahedron

An octahedron is a Platonic solid with:

- 8 faces

- 6 vertices

- 12 edges

The octahedron is bounded by eight equilateral triangles. It rotates freely when held by two opposite vertices.

In Ancient Greece, the octahedron corresponds to the element Air.

Dodecahedron

Definition: Dodecahedron

A dodecahedron is a Platonic solid with:

- 12 faces

- 20 vertices

- 30 edges

The dodecahedron is bounded by twelve congruent regular pentagons.

In Ancient Greece, the dodecahedron corresponds to the universe because the zodiac has twelve signs corresponding to the twelve faces of the dodecahedron.

Icosahedron

Definition: Icosahedron

An icosahedron is a Platonic solid with:

- 20 faces

- 12 vertices

- 30 edges

The icosahedron is bounded by twenty equilateral triangles and has the largest volume for its surface area of the Platonic solids.

In Ancient Greece, the icosahedron represents the property of wetness and corresponds to the element of Water.

Thinking Out Loud:

Where in your life might you have seen the Platonic solids? How might the Platonic solids be useful?

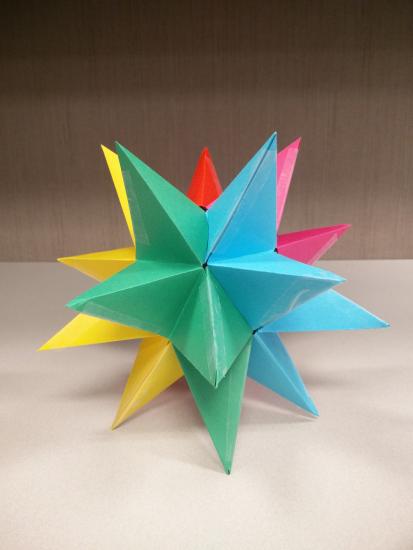

ACTIVITY

Activity: Holiday decorations

-

Materials/Equipment:

- Card stock, Bristol board, used greeting cards or some other stuff but not too thick paper. You’ll need lots of it for a class.

- White glue.

CONSTRUCTION DIRECTIONS:

Step 1: Fix a radius on your circle cutter and mass produce a lot of circles. For example, if students were making cubes they’d need 6 per cube, if they make the icosahedrons they’ll need 20 circles (in my opinion icosahedrons with flaps are the nicest to make!) Keeping the radius fairly small (eg 4 inches on my non-metric circle cutter) would let you get away with using up less paper and makes a nice sized decoration. Produce some extra circles for errors and a geometry discussion with students.

Step 2: Take one of the circles and inscribe the template square (for cubes) or equilateral triangle (for icosahedrons). (Fold to get the center of the circle and for the square the folds locate the vertices for the square. For the triangle you can pull out a protractor and measure off 3 120 degree angles to get the vertices.) Cut out the template shape.

Step 3: Trace this shape and trace it out on as many circles as you need. Work fast – slight imperfections are ok. Now take a rule and a nail (or something else a little sharp) and quickly trace over the lines to break the surface of the cardstock. Fold the sides up to get little ‘cups’ with a square or triangular base. I have gone through steps one to three and made over 120 circles folded into cups in one hour.

Step 4: Bring nets of the cube and icosahedrons (or pictures from the websites mentioned) to help guide the students in putting the shape together. Students will be gluing the flaps together to form the cube or icosahedrons. You have the option of gluing the flaps out or flaps in. The icosahedrons look really neat with the flaps out. Given them the white glue and lead them through putting it together. Again, make one yourself in advance so you can get a feel for how much guidance your students will need and if they need an older helper to finish it off.

In fact. you can also construct other polyhedra (the Archimedean solids for example) using this technique. I’d need the Pythagorean theorem to construct a cuboctahedron.

Video Demonstration can be found here.

References:

- The Mathlab.com, Making the Dice of the Gods, http://www.themathlab.com/wonders/godsdice/godsdice.htm (as of Oct. 6, 2012)

- Aunt Annie’s Crafts, Platonic solids, http://www.auntannie.com/Geometric/PlatonicSolids/ (as if Oct. 6, 2012).

- La Haye, Roberta. "Geometry and Art with a Circle Cutter." Proceedings of Bridges 2012: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture. 2012.

The article can be found in https://archive.bridgesmathart.org/2...s2012-425.html

Euler's Formula

Definition:Euler's Formula

There is a relationship between the number of faces (F), vertices (V), and edges (E) in any convex polyhedron, and knowing this relationship enables us to construct a formula that connects the number of faces, vertices, and edges.

Euler's formula for convex polyhedra is: \(V + F = E + 2\)

That is: for any convex polyhedron, the number of vertices added to the number of faces is equal to two more than the number of edges.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Consider the dodecahedron:

\(V = 20, \, F = 12, \, E = 30\).

Let's see if Euler's formula holds:

\(V + F = E + 2\)

\(V + F=(20) + (12)=32 \) and \(E + 2= (30) + 2=32\)

Excellent! It works.

Truncated Regular Polyhedra

Definition:

Truncated regular polyhedra, which are also sometimes called Archimedean solids, must:

- Be composed of regular polygons

- Have identical vertices

- Not be a Platonic solid, prism, or anti-prism.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\):

Non-Convex Uniform Polyhedra (Kepler-Poinsot Solids)

It is possible to construct regular polyhedra that are not convex - that is, shapes that have identical faces but also have incuts or void spaces. These solids are sometimes called Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra. These shapes can be made by building a regular dodecahedron or icosahedron and adding pyramidal or pentagramal volumes to each face. These polyhedra do not always satisfy the Euler relation as it relates to Platonic solids.

There are four Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra: three based on the dodecahedron and one built upon the icosahedron.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Kepler-poinsot solids

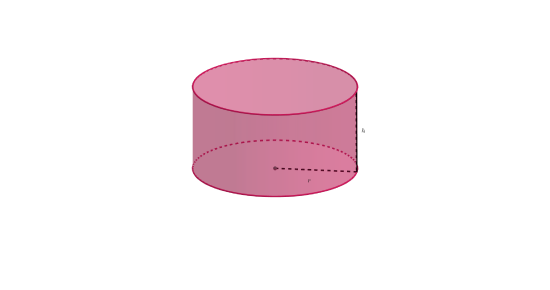

Cylinders, Spheres, and Cones

Definition: Cylinders

Cylinders are prisms with two circular faces. Their volume is given by

\[V_{cylinder} = \pi r^2h\]

and surface area by

\[S_{cylinder} = \left( 2 \pi r \right) \left( r + h \right) \]

where \(r\) is the radius of the circular faces, and \(h\) is the distance between the two circular faces of the cylinder, or its height. A cylinder does not need perfect circles as its bases, provided both are congruent. The most common alternative to a circular base is an elliptical one. A shape with this base would be called an elliptical cylinder.

Definition: Spheres

Spheres are perfectly round objects that are found in a 3-dimensional Euclidean space. Technically, they have no thickness and are hollow. The volume described by a sphere is given by

\[\displaystyle V_{sphere}= \dfrac{4}{3} \pi r^3\]

here \(r\) is the radius of the sphere. The surface area of a sphere is given by

\[S_{sphere} = 4 \pi r^2.\]

Definition: Cones

Cones are pyramids with circular bases. Their volume is given by

\[V_{cone} = \dfrac{1}{3} A_Bh \]

where h is the height of the cone and AB is the area of the base. The surface area of a cone is described by the formula \(S = \pi r^2+ \pi r \surd \left( r^2 + h^2 \right)\)