A central concept in number theory is divisibility.

Consider the integer . For , we say that divides if for some . If divides , we write , and we may say that is a divisor of , or that is a multiple of , or that is a divisible of . If does not divide , then we write .

We first state some simple facts about divisibility:

Theorem

For all , we have

- and ;

- if and only if ;

- if and only if if and only if ;

- and implies ;

- and implies .

Proof

These properties can be easily derived from the definition of divisibility, using elementary algebraic properties of the integers. For example, because we can write ; because we can write ; because we can write . We leave it as an easy exercise for the reader to verify the remaining properties.

We make a simple observation: if and , then . Indeed, if for some integer , then and ; it follows that , , and so

Theorem

For all , we have and if and only if . In particular, for every , we have if and only if .

Proof

Clearly, if , then and . So let us assume that and , and prove that . If either of or are zero, then the other must be zero as well. So assume that neither is zero. By the above observation, implies , and implies ; Thus, , and so . That proves the first statements. The second statement follows from the first by setting , and noting that .

The product of any two non-zero integers is again non-zero. This implies the usual cancellation law: if , , and are integers such that and , then we must have ; indeed, implies , and so implies , and hence .

Primes and Composites

Let be a positive integer. Trivially, and divide . If and no other positive integers besides and divide , then we say is prime. If but is not prime, then we say that is composite. The number is not considered to be either prime or composite. Evidently, is composite if and only if for some integers with and . The first few primes are

2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, ....

While it is possible to extend the definition of prime and composite to negative integers, we shall not do so in this text: whenever we speak of a prime or composite number, we mean a positive integer.

A basic fact is that every non-zero integer can be expressed as a signed product of primes in an essentially unique way. More precisely:

Theorem : fundamental theorem of arithmetic

Every non-zero integer can be expressed as

where are distinct primes and are positive integers. Moreover, this expression is unique, up to a reordering of the primes.

Note

Note that if in the above theorem, then , and the product of zero terms is interpreted (as usual) as 1.

The theorem intuitively says that the primes act as the “building blocks” out of which all non-zero integers can be formed by multiplication (and negation). The reader may be so familiar with this fact that he may feel it is somehow “self evident,” requiring no proof; however, this feeling is simply a delusion, and most of the rest of this section and the next are devoted to developing a proof of this theorem. We shall give a quite leisurely proof, introducing a number of other very important tools and concepts along the way that will be useful later.

proof

To prove Theorem 1.3, we may clearly assume that is positive, since otherwise, we may multiply by −1 and reduce to the case where is positive.

The proof of the existence part of Theorem 1.3 is easy. This amounts to showing that every positive integer can be expressed as a product (possibly empty) of primes. We may prove this by induction on . If , the statement is true, as n is the product of zero primes. Now let , and assume that every positive integer smaller than n can be expressed as a product of primes. If is a prime, then the statement is true, as is the product of one prime. Assume, then, that is composite, so that there exist with , , and . By the induction hypothesis, both and can be expressed as a product of primes, and so the same holds for .

The uniqueness part of Theorem 1.3 is the hard part(Check the section 2). An essential ingredient in this proof is the following:

Theorem : Division with remainder property

Let with . Then there exist unique such that and .

Proof

Consider the set of non-negative integers of the form with . This set is clearly non-empty; indeed, if , set , and if , set . Since every non-empty set of non-negative integers contains a minimum, we define to be the smallest element of . By definition, is of the form for some , and . Also, we must have , since otherwise, would be an element of smaller than , contradicting the minimality of ; indeed, if , then we would have .

That proves the existence of and . For uniqueness, suppose that and , where and . Then subtracting these two equations and rearranging terms, we obtain

Thus, is a multiple of ; however, and implies ; therefore, the only possibility is . Moreover, and implies .

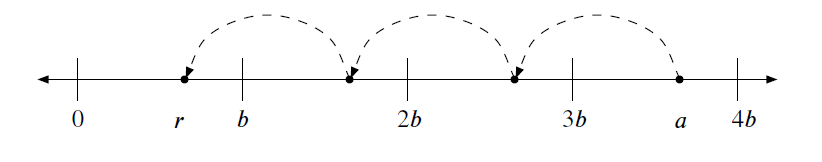

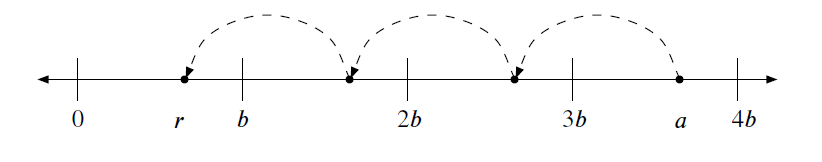

Theorem can be visualized as follows:

Starting with , we subtract (or add, if is negative) the value until we end up with a number in the interval .

Floor and Ceilings

Let us briefly recall the usual floor and ceiling functions, denote and , respectively. These are functions from (the real numbers) to . For , is the greatest integer ; equivalently, is the unique integer such that , or put another way, such that for some . Also, is the smallest integer ; equivalently, is the unique integer such that , or put another way, such that for some .

The mod operator

Now let with . If and are the unique integers from Theorem 1.4 that satisfy and , we define

that is, denotes the remainder in dividing by . It is clear that if and only if . Dividing both sides of the equation by , we obtain . Since and , we see that . Thus,

One can use this equation to extend the definition of to all integers and , with ; that is, for , we simply define to be .

Theorem may be generalized so that when dividing an integer by a positive integer , the remainder is placed in an interval other than . Let be any real number, and consider the interval . As the reader may easily verify, this interval contains precisely integers, namely, . Applying Theorem 1.4 with in place of , we obtain:

Theorem

Let with , and let . Then there exist unique such that and .

EXERCISE 1.1 Let with . Show that if and only if .

EXERCISE 1.2 Let be a composite integer. Show that there exists a prime dividing , with .

EXERCISE 1.3 Let be a positive integer. Show that for every real number , the number of multiples of in the interval is ; in particular, for every interger , the number of multiples of among is .

EXERCISE 1.4 Let . Show that .

EXERCISE 1.5 Let and with . Show that ; in particular, for all positive integers .

EXERCISE 1.6 Let with . Show that .

EXERCISE 1.7 Show that Theorem 1.5 also holds for the interval . Does it hold in general for the intervals or ?