6.5: Heating, Cooling and Mixing

- Page ID

- 212059

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The previous section examined applications of exponential growth and decay. This section examines other applications involving separable IVPs that can be solved using the methods of Section 6.3.

Newton’s Law of Cooling

Some rates of change depend on how far the value of a variable quantity is from a fixed value. The rate at which a hot cup of soup cools (or a cool cup of water warms up) is proportional to the difference in temperature between the soup (or water) and the surrounding air. This principle, called Newton's Law of Cooling (or Warming), provides an approximate model for temperature change when the object in question is subject to forced convection (a steady breeze, for example). It also applies to natural convection (no breeze or draft) if the temperature difference between the object and the surrounding air is not too great.

If: \(f(t)\) is the temperature at time \(t\) of an object in an atmosphere with constant temperature \(a\)

then: the rate of change of \(f\) is proportional to the difference between \(f\) and \(a\): \(f'(t) = k\left[f(t)-a \right]\) and the solution to this ODE is:\[f(t) = a + \left[f(0) - a\right]\cdot e^{kt}\nonumber\]

The statement that the rate of change is proportional to the difference:\[f'(t) = k\left[f(t) - a\right]\nonumber\]can be observed by experimentation.

Proof

This ODE is separable, so we can solve it using the methods of Section 6.3. Or we can let \(g(t) = f(t)-a\) so that \(g'(t) = f'(t)\) and \(g(0) = f(0)-a\), transforming the ODE for \(f(t)\) into the IVP:\[g'(t) = kg(t), \qquad g(0) = f(0)-a\nonumber\]From Section 6.4 we know that \(g(t) = g(0)\cdot e^{kt}\) so that:\[f(t) - a = \left[f(0)-a\right]e^{kt} \quad \Rightarrow \quad f(t) = a + \left[f(0)-a\right]e^{kt}\nonumber\]

The figure below shows some functions with different initial values that all satisfy the differential equation \(f'(t) = f(t) - 5\):

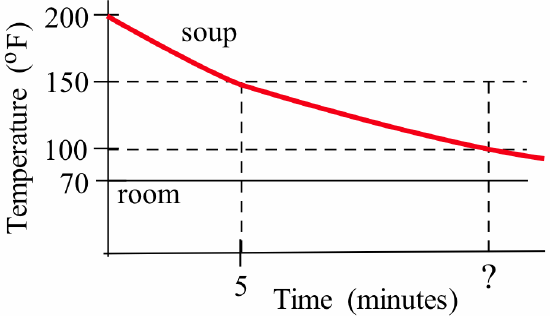

A cup of soup sits on a counter in a room with temperature 70° F. When first poured into the cup, the soup had a temperature of 200° F, and five minutes later its temperature was 150° F:

- Find a formula for the soup’s temperature at any time \(t >0\).

- How long does it take for the soup to cool to 100° F?

- What will the temperature of the soup be after a “long” time?

Solution

- If \(f(t)\) is the soup’s temperature \(t\) minutes after being poured and the room temperature is \(a = 70^{\circ}\) F, then we know that \(f(0) = 200^\circ\) F so \(f'(t) = k\left[f(t) - 70\right]\) and hence:\[f(t) = 70 + \left[200 - 70\right]\cdot e^{kt} = 70 + 130\cdot e^{kt}\nonumber\]We can now use the information that \(f(5) = 150^\circ\) F to find the value of \(k\) and an equation for \(f(t)\):\[150 = f(5) = 70 + 130. e^{k\cdot 5} \ \Rightarrow \ k = \frac15 \cdot \ln\left(\frac{80}{130}\right) \approx -0.0971\nonumber\]so \(f(t) \approx 70 + 130\cdot e^{-0.0971t}\).

- We now want to find the time \(t\) so that \(f(t) = 100\):\[100 = f(t) \approx 70 + 130\cdot e^{-0.0971 t} \ \Rightarrow \ 30 = 130\cdot e^{-0.0971 t} \ \Rightarrow \ t = \frac{\ln\left(\frac{30}{130}\right)}{-0.0971} \approx 15.1 \ \mbox{minutes}\nonumber\]

- After a “long time” means for very large values of \(t\):\[\lim_{t \to \infty}\, \left[70 + 130\cdot e^{-0.0971 t}\right] = 70\nonumber\]so (eventually) the temperature of the soup approaches 70° F, the temperature of the room.

After eating some of the soup in the preceding Example, you refrigerate the leftover soup, cooling it to a temperature of 37° F. At noon the next day, you move the container of soup from the refrigerator back to the 70° F room. One hour later, the temperature of the soup is 48° F. At what time will the temperature of the soup be 60° F?

- Answer

-

The temperature of the soup \(t\) minutes after being removed from the refrigerator is:\[f(t) = 70 +\left[37-70\right]\cdot e^{kt} = 70-33e^{kt}\nonumber\]Using the fact that \(f(60) = 48\):\[48 = 70-33e^{kt} \ \Rightarrow \ \frac{22}{33} = e^{60k} \ \Rightarrow \ k = \frac{1}{60}\cdot \ln\left(\frac{22}{33}\right) \approx -0.006758\nonumber\]so that \(f(t) \approx 70-33e^{-0.006758t}\). If \(\displaystyle 60 = 70-33e^{-0.006758T}\) then:\[\frac{10}{33} = e^{-0.006758T} \ \Rightarrow \ T = -\frac{1}{0.006758}\cdot\ln\left(\frac{10}{33}\right) \approx 176.7\nonumber\]so the soup will warm up to 60\)^{\circ}\) F after roughly three hours.

Mixing

Many important applications involve one substance being mixed into another: chlorine being slowly introduced into a swimming pool, a toxic gas being mixed into the air in a closed room, or (in a classic example) salt (NaCl) being mixed into water (H2O).

A tank contains 350 grams of salt dissolved in 10 liters of water. Pure water begins flowing into the tank at 2 liters per hour, and the well-mixed solution flows out of the tank at the same rate.

- Find a formula for the amount of salt in the tank \(t\) hours after this process begins.

- Find a formula for the concentration salt in the tank.

- What will the concentration be after a “long” time?

Solution

- Let \(A(t)\) be the amount of salt (in grams) \(t\) hours after this process begins. We know that \(A(0) = 350\). Now consider \(A'(t)\), the rate at which amount of salt in the tank is changing with respect to time. No salt is flowing in, but the rate at which salt is leaving the tank is:\[\frac{A(t)\mbox{ g}}{10\mbox{ L}} \cdot 2\ \frac{\mbox{L}}{\mbox{hr}} = 0.2A(t) \ \frac{\mbox{g}}{\mbox{hr}}\nonumber\]which gives us the IVP:\[\frac{dA}{dt} = - 0.2A, \quad A(0) = 350\nonumber\]This is a separable IVP with solution \(\displaystyle A(t) = 350e^{-0.2t}\).

- The concentration is:\[C(t) = \frac{A(t)\mbox{ g}}{10\mbox{ L}} = \frac{350e^{-0.2t}\mbox{ g}}{10\mbox{ L}} = 35e^{-0.2t} \ \frac{\mbox{g}}{\mbox{L}}\nonumber\]

- After a “long” time:\[\lim_{t\to\infty}\, C(t) = \lim_{t\to\infty}\, 35e^{-0.2t} = 0\nonumber\]This seems reasonable: after a very long time, most of the original salt in the tank will be flushed out, replaced by pure water.

A tank contains 300 grams of salt dissolved in 10 liters of water. Water containing 15 grams of salt per liter begins flowing into the tank at a rate of 4 liters per hour, and the well-mixed solution flows out of the tank at the same rate.

- Find a formula for the amount of salt in the tank \(t\) hours after this process begins.

- Find a formula for the concentration salt in the tank.

- What will the concentration be after a “long” time?

- Answer

- If \(A(t)\) is the amount of salt (in grams) \(t\) hours after this process begins, then:\[\frac{dA}{dt} = 15\, \frac{\mbox{g}}{\mbox{L}} \cdot 4 \, \frac{\mbox{L}}{\mbox{hr}} - \frac{A\mbox{ g}}{10\mbox{ L}} \cdot 4 \, \frac{\mbox{L}}{\mbox{hr}}\nonumber\]so \(A(t)\) satisfies the IVP:\[\frac{dA}{dt} = 60 -\frac25 A, \quad A(0) = 300\nonumber\]

- This IVP is separable, so we can solve it: \begin{align*} \int \frac{1}{60-\frac25 A} \, dA = \int 1\, dt \ &\Rightarrow \ -\frac52 \ln\left(\left|60-\frac25 A\right|\right) = t + C \\ &\Rightarrow \ \ln\left(\left|60-\frac25 A\right|\right) = -\frac25 t + K\\ \end{align*} Using the initial condition:\[\ln\left(\left|60-\frac25 \cdot 300 \right|\right) = -\frac25 \cdot 0 + K \ \Rightarrow \ K = \ln(60)\nonumber\]so that:\[\ln\left(\left|60-\frac25 A\right|\right) = -\frac25 t + \ln(60) \ \Rightarrow \ 60-\frac25 A = - 60 e^{-\frac25 t}\nonumber\]where we need to use a \(-\) sign when “undoing” the absolute value to ensure that the initial condition \(A(0) = 300\) will still hold. Solving for \(A\) yields \(\displaystyle A(t) = 150\left[1+e^{-\frac25 t}\right]\).

- Divide by the volume to get \(\displaystyle C(t) = 15\left[1+e^{-\frac25 t}\right]\).

- \(\displaystyle \lim_{t\to\infty} \, 15\left[1+e^{-\frac25 t}\right] = 15\), so the limiting concentration is 15 g/L (the concentration of solution flowing into the tank, as expected).

If the volume of liquid in the tank does not remain constant, the differential equation can become a bit more complicated.

A 20-liter tank contains 250 grams of salt dissolved in 10 liters of water. Pure water begins flowing into the tank at a rate of 5 liters per hour, and the well-mixed solution flows out of the tank at a rate of 3 liters per hour.

- Find a formula for the amount of salt in the tank \(t\) hours after this process begins.

- Find a formula for the concentration salt in the tank.

- What will the concentration be at the moment the tank overflows?

Solution

- Let \(A(t)\) be the amount of salt (in grams) \(t\) hours after this process begins. We know that \(A(0) = 250\) and that the volume of water in the tank is \(V(t) = 10+2t\) (because 5 liters of water flow in each hour, but only 3 liters flow out). No salt is flowing into the tank, but the rate at which salt is leaving the tank is:\[\frac{A(t)\mbox{ g}}{10+2t\mbox{ L}} \cdot 3\ \frac{\mbox{L}}{\mbox{hr}} = \frac{3A(t)}{10+2t} \ \frac{\mbox{g}}{\mbox{hr}}\nonumber\] which gives us the IVP:\[\frac{dA}{dt} = -\frac{3A}{10+2t}, \quad A(0) = 250\nonumber\]This is a separable IVP:\[\frac{1}{A} \cdot \frac{dA}{dt} = -\frac{3}{10+2t} \ \Rightarrow \ \ln(A) = - \frac32 \ln\left(10+2t\right) + C\nonumber\]Using the initial condition:\[\ln(250) = -\frac32\ln(10) + C \ \Rightarrow \ C = \ln(250) + \frac32\ln(10)\nonumber\]Solving for \(A\): \begin{align*} \ln(A) &= \ln\left(10+2t\right)^{-\frac32} + \ln(250) + \ln(10^{\frac32}) \\ \Rightarrow \quad A(t) &= \left(10+2t\right)^{-\frac32} \cdot 250 \cdot 10\sqrt{10} = \frac{2500\sqrt{10}}{\left(10+2t\right)^{\frac32}} \end{align*}

- The concentration is:\[C(t) = \frac{A(t)\mbox{ g}}{10+2t\mbox{ L}} = \frac{2500\sqrt{10}}{\left(10+2t\right)^{\frac52}}\ \frac{\mbox{g}}{\mbox{L}}\nonumber\]

- The tank overflows when \(20=10+2t \Rightarrow t = 5\), at which time the concentration is:\[C(5) = \frac{2500\sqrt{10}}{\left(10+2\cdot 5\right)^{\frac52}} = \frac{25}{4\sqrt{2}}\ \frac{\mbox{g}}{\mbox{L}}\nonumber\]or about 4.42 grams per liter.

A 20-liter tank contains 250 grams of salt dissolved in 10 liters of water. Water containing 35 grams of salt per liter begins flowing into the tank at a rate of 5 liters per hour, and the well-mixed solution flows out of the tank at a rate of 3 liters per hour. Set up an initial value problem to model the amount of salt in the tank \(t\) hours after this process begins. Is the ODE separable?

- Answer

-

If \(A(t)\) is the amount of salt (in grams) \(t\) hours after this process begins, then:\[\frac{dA}{dt} = 35\, \frac{\mbox{g}}{\mbox{L}} \cdot 5 \, \frac{\mbox{L}}{\mbox{hr}} - \frac{A\mbox{ g}}{(10+2t)\mbox{ L}} \cdot 3 \, \frac{\mbox{L}}{\mbox{hr}}\nonumber\]so \(A(t)\) satisfies the IVP:\[\frac{dA}{dt} = 175 -\frac{3A}{10+2t}, \quad A(0) = 250\nonumber\]This is not a separable equation. (You will learn how to solve equations of this type in a course about differential equations. For now, you could construct a direction field to analyze the behavior of solutions to the ODE.)</li>

Problems

- You remove a cheesecake from the oven with an ideal internal temperature of 165° F and place it into a 35° F refrigerator. After 10 minutes, the cheesecake has cooled to 150° F. If you must wait until the cheesecake has cooled to 70° F before you eat it, how long will you have to wait?

- When a pot of hot (200° F) water is removed from the stove in a 70° F kitchen, it takes 15 minutes to cool to a temperature of 150° F.

- Find a formula for the temperature of the water \(t\) minutes after it is removed from the stove.

- When will the water be 100° F?

- When will the water be 80° F?

- When will the water be 60° F?

- When you remove the pot of 200° F water from the previous problem from the stove and take it outside on a 40° F day, it only takes 4 minutes to cool to a temperature of 150° F.

- Find a formula for the temperature of the water \(t\) minutes after it is removed from the stove.

- When will the water be 100° F?

- When will the water be 80° F?

- When will the water be 60° F?

- When you remove a pitcher of orange juice from a 40° F refrigerator into a 70° F kitchen, it takes 25 minutes to warm up to a temperature of 60° F.

- Estimate the temperature of the juice \(t\) minutes after you removed it from the refrigerator.

- When was the juice 50° F?

- When will the juice be 65° F?

- A tank initially holds 100 gallons of brine (water mixed with salt) containing 50 pounds of dissolved salt. Pure water flows into the tank at a rate of 3 gallons per minute and flows out at the same rate, with the brine concentration kept roughly uniform by constant stirring. How much salt remains in the tank after one hour?

- A tank initially holds 1000 liters of brine containing 8 kg of dissolved salt. Pure water enters the tank at a rate of 10 liters per minute and brine (with concentration kept roughly uniform by constant stirring) leaves the tank at the same rate.

- Find the concentration of salt in the tank after half an hour.

- Determine the limiting concentration of salt in the tank after “a very long time.”

- A large tank initially contains 100 gallons of brine (water mixed with salt) containing 50 pounds of dissolved salt. Pure water flows into the tank at a rate of 3 gallons per minute and flows out at 2 gallons per minute, with the brine concentration kept roughly uniform by constant stirring. How much salt remains in the tank after one hour?

- A tank initially holds 1000 liters of pure water. Brine containing 8 g of dissolved salt per liter enters the tank at a rate of 10 liters per minute and the well-mixed solution leaves the tank at the same rate.

- Find the concentration of salt in the tank after half an hour.

- Determine the limiting concentration of salt in the tank after “a very long time.”